From Ideas to Change: Emergent Design Practices to Overcome Implementation Challenges When Designing in the Public Sector

Thomas van Arkel 1,*, Nynke Tromp 1,2, Deger Ozkaramanli 1, and Bregje F. van Eekelen 1,3

1 Delft University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands

2 Dutch Design Foundation, Eindhoven, the Netherlands

3 Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

There is renewed interest in leveraging design in the public sector to address complex societal challenges. While collaborations between designers and public sector organizations hold potential, they often face significant challenges, leading to minimal uptake and impact of project outcomes. Hence, in this article, we investigate implementation as a practice, namely the practice of turning ideas into action. The study retrospectively explores implementation challenges in collaborations between external designers and public sector organizations. Based on a multiple case study, we identified eight implementation challenges across initiative, organization, and system levels, along with 13 design practices that help address these challenges. Our findings highlight that effective implementation requires designers to navigate inherent tensions between temporary and enduring elements, situated and systemic approaches, and stabilising and transforming organizational practices. This research contributes to understanding design’s impact in the public sector by proposing a tension-driven framework for implementation, emphasising the need to shift focus from generating meaningful ideas to strategically orchestrating their practical realisation and sustainable impact.

Keywords – Design Practices, Societal Impact, Implementation, Public Sector Innovation.

Relevance to Design Practice – The article highlights the need for a more continuous and adaptive approach to implementation by providing some initial pointers towards the activities and their respective trade-offs to aid the implementation of project outcomes when designing in the public sector.

Citation: van Arkel, T., Tromp, N., Ozkaramanli, D., & van Eekelen, B. F. (2025). From ideas to change: Emergent design practices to overcome implementation challenges when designing in the public sector. International Journal of Design, 19(2), 57-77. https://doi.org/10.57698/v19i2.05

Received May 31, 2024; Accepted May 18, 2025; Published August 31, 2025.

Copyright: © 2025 van Arkel, Tromp, Ozkaramanli, & van Eekelen. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: t.vanarkel@tudelft.nl

Thomas van Arkel is a Ph.D. candidate at Delft University of Technology. His research focuses on understanding how design interventions can move beyond localised, ephemeral impacts to foster broader, structural transformation of organizational practices in public organizations in the context of complex societal challenges. He is particularly interested in how design interventions can balance challenging and reproducing organizational structures—and how such interventions can be appropriated, translated, and scaled across different contexts to achieve broader systemic impact. His practice is situated at the interface between theory and practice, where he closely collaborates with design practitioners and public organizations. He is part of the Systemic Design Lab at TU Delft, a cross-departmental lab dedicated to developing and applying knowledge about the role of design in generating systemic change.

Nynke Tromp holds a Ph.D. and is currently the program director at the Dutch Design Foundation, where she develops the public design practice in the Netherlands, commissioned by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. She is co-founder of the Systemic Design Lab, co-founder of Redesigning Psychiatry, and author of Designing for Society (2019). This work was conducted when Tromp worked as an associate professor of Social Design & Behaviour Change at the Department of Human-Centred Design, Delft University of Technology. She was also director of the MSc program Design for Interaction and part of the management team of the Delft Design for Values Institute. Her research focused on the role of design in addressing complex societal issues, both through the capacity of designed artifacts to shape behaviour and the methodological value of design thinking and reframing. Her work spanned a variety of domains, including democracy, mental health, food consumption, safety, and wildlife trade.

Deger Ozkaramanli is an assistant professor of Human-Centred Design at Delft University of Technology. Her research sits at the intersection of design methods, transdisciplinary collaboration, and design ethics. She developed Dilemma-Driven Design in earlier work, and using value conflicts as a lens, she currently researches the contribution of design methods and practices to transdisciplinary collaboration. Deger leads the Design Research Society Special Interest Group on Design Ethics with an international and interdisciplinary team of co-conveners.

Bregje F. van Eekelen is a full professor of Design, Culture and Society at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering at Delft University of Technology. She is also a professor of Smart Cities Design, Culture and Society at the Erasmus School of Social and Behavioural Sciences. As an anthropologist/historian of knowledge, van Eekelen draws on insights from the social sciences (anthropology) and the humanities (history, cultural analysis). Her chair focuses on the reciprocal relations between the world of design (its artifacts, practices, and concepts) and the social, cultural, economic, and political worlds in which design emerges, where these relations are studied dynamically.

Introduction

Recently, there has been a renewed interest by public sector organizations in the value of design practices regarding how they could contribute to addressing complex societal challenges (Bason, 2018; van Buuren et al., 2020). Design practices are said to have characteristics that make them suitable for the ambiguous, uncertain, and networked nature of complex issues (Buchanan, 1992; Dorst, 2015). Leveraging specific design competencies can complement traditional policymaking processes and public service delivery (van Arkel & Tromp, 2024). Hence, (social) designers are increasingly collaborating with organizations across the public sector.

However, designing in the public sector—for example, by collaborating with ministries, executive agencies, and municipalities—differs from designing in other design contexts (e.g., the commercial sector). Public sector organizations are often not well equipped to carry out transition tasks (Braams, 2023), the public sector lacks an innovation culture (Bason, 2018; Schaminée, 2019), and the way designers work is at odds with conventional operational modes within public organizations (Brinkman et al., 2023). Collaborations between designers and public organizations often end prematurely, and design proposals often have minimal adoption and uptake (Brinkman et al., 2024), and thus impact. Previous work mostly focused on ways to make the public sector more inviting and receptive to design approaches by, for example, understanding how to embed design practices in public sector organizations (Kim, 2023; Peters, 2020), identifying strategic actions that practitioners can take to enhance the application of design-based approaches (Brinkman et al., 2023), or ensuring the necessary conditions for design-based approaches to achieve impact (Yee & White, 2016). These approaches to increase impact often treat design as an immutable practice that is worth embedding based on the assumed value it provides.

However, there may also be aspects of design practices themselves that may explain the minimal adoption, realisation, and continuation of ideas and initiatives in the public sector, i.e., implementation. Previous work highlights the existence of a so-called threshold to implementation when design practices are applied in public sector organizations (Pirinen et al., 2022). Applications of design-based approaches seem to concentrate on the front-end, generative stages of the design process (Pirinen et al., 2022), often not intending or attempting to help implement the proposed designs (Hermus et al., 2020). This aligns with the idea that design processes (e.g., workshops and generative sessions) often give an illusion of change (Bailey, 2021; Julier & Kimbell, 2019), whereas “real change happens in the slow, tricky, and political work of implementation” (Julier & Kimbell, 2019, p. 18). Projects are often delivered at the prototyping stage, demonstrating the potential of outcomes while at the same time being ‘things-that-are-not-quite-objects-yet’ (Corsín Jiménez, 2014, p. 383) that are just as likely to be abandoned or modified as carried through to delivery (Bailey, 2021). This points to a lack of implementation practices when designing in the public sector. Current design methodologies that support designers in addressing complex societal challenges focus on the generation of meaningful ideas and not on how to implement those ideas, which limits design’s potential for change.

Hence, in this paper, we will explore the question: What emergent implementation practices can be identified in collaborations between external designers and public sector organizations when working on complex societal challenges? The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: First, we explore how to understand implementation in a complex public sector context. Next, we outline our research method and case studies, followed by the findings where we describe implementation challenges across initiative, organization, and system levels, along with emergent implementation practices that address these challenges. Finally, we discuss the results and implications for design practice, highlighting a tension-driven approach to implementation, and conclude with future research directions.

Understanding Implementation in a Complex Public Sector Context

Designing for complex societal challenges requires different approaches than conventional human-centred methods, as these complex challenges lack clear end-users and/or clients (Dorst, 2019). Rather than producing discrete products or services, addressing these challenges requires systemic shifts involving multiple interventions to generate change in systems, social structure, and institutions (Loorbach et al., 2017; Norman & Stappers, 2015; van der Bijl-Brouwer et al., 2021) to affect the recurring and reproductive aspects of human interactions (Lee, 2024). Similar to how shifting from product to service implementation requires different methods and approaches (Yu, 2021), addressing complex societal challenges requires rethinking implementation at the intersection of design practices and public sector organizations.

Here we see implementation as the continuous, adaptive practice of turning design outcomes into sustained action and impact (Boyer et al., 2013; Raviv, 2023). Unlike traditional understandings that view implementation as a linear, final phase of a design process, we conceptualise it as an ongoing practice beginning at a design initiative’s outset. Just as service implementation differs from product implementation as it requires changes to actor roles, practices, resources, and processes (Yu, 2021), implementation for complex societal challenges involves consolidating the effects of intervening and orchestrating activities to ensure design outcomes materialise as intended, gain traction, adapt to contextual requirements, and potentially transform existing structures.

Implementation of design outcomes in the public sector presents unique challenges to designers. Public organizations operate within bureaucratic, regulatory, and political structures that enable and constrain how change can occur (Bason, 2017). Public organizations must balance efficiency, equity, legitimacy, and other values whilst being subject to democratic accountability and political scrutiny (Bryson et al., 2014; Moore, 1995). This context often leads to incremental rather than disruptive change, as radical innovations may face resistance due to risk aversion and the need to maintain public trust through stability (Hartley, 2005; Torfing & Triantafillou, 2016).

This creates an inherent tension: public organizations tend to favour incremental change, whilst complex societal challenges often demand more systemic or transformative approaches. This apparent contradiction raises a fundamental question: how could design function as an engine for wider societal transformation (Sangiorgi, 2010) when collaborating with established public organizations that are structurally oriented towards stability and incremental improvement?

At the same time, tensions, dilemmas, and paradoxes have been identified as promising sites of innovation for design practices (Dorst, 2006; Neuhoff et al., 2022; Ozkaramanli et al., 2016; Tromp & Hekkert, 2019). Hence, we pay particular attention to these tensions to obtain a complex understanding of the patterns or relationships between emergent implementation practices. We explore implementation along three nested levels: the immediate collaborative project space (initiative level), the broader organizational environment (organization level), and the wider systemic context of the complex issue being addressed (system level). To explore practices within and across these levels, we adopt a practice-theory approach to analysing implementation, approaching design-as-practice (Kimbell, 2012), where design can be seen as a bundle of related socio-material practices. A practice is a routinised pattern of interconnected bodily activities, mental processes, material elements, and shared understandings that is collectively produced and reproduced by groups of individuals across time and space (Reckwitz, 2002; Schatzki, 2001; Shove et al., 2012).

Within the context of design, we define design practices as drawing from multiple competencies in the repertoire that design practitioners bring to complex societal challenges in the public sector (van Arkel & Tromp, 2024). These four core competencies—integrating, reframing, formgiving, and orchestrating—jointly provide distinct value when designing for complex issues. Integrating involves weighing and synthesising diverse perspectives and reconciling competing demands into coherent wholes. Reframing enables the exploration of alternative interpretations to arrive at new perspectives and possibilities, often through metaphorical reasoning. Formgiving focuses on shaping ideas by moving between abstraction levels, creating tangible interventions, and generating knowledge through making. Orchestrating involves bringing together different parties to structure productive collaboration and navigate change processes, often through developing boundary objects that facilitate constructive conversation between actors.

Research Method

To understand the challenges of implementation practices, we adopted a retrospective multiple case study approach. This helps to trace collaborative processes over time in a way that we can study events in their real-world context (Yin, 2014), which contributes to the identification of challenges as well as design practices that aim to deal with these challenges. The unit of analysis in this study is a collaboration between external designers and a public safety and security organization that has completed at least one initial project. Although individual projects do not necessarily lead to transformation by themselves (Dorst & Watson, 2023), they do provide insights into the collaboration during the project and what happened after, given that design projects have a beginning and an end1.

In addition, we define project outcomes as the range of outputs, effects, and changes resulting from the collaborations as systems change results from changes in multiple co-evolving spaces (van der Bijl-Brouwer et al., 2021). Project outcomes can be tangible artefacts or interventions, new or reconfigured relationships, new knowledge and skills, or shifts in organizational practices that emerge through the collaborative process and may continue to evolve after the project concludes.

Context of the Study

This study was conducted in a research consortium composed of three partners: a social design group that is part of a large consultancy firm, a small-to-medium-sized social design agency, and a freelance social designer. All three partners shared the same question on the minimal impact of social design, particularly in the safety and security domain.

Case Selection and Sampling

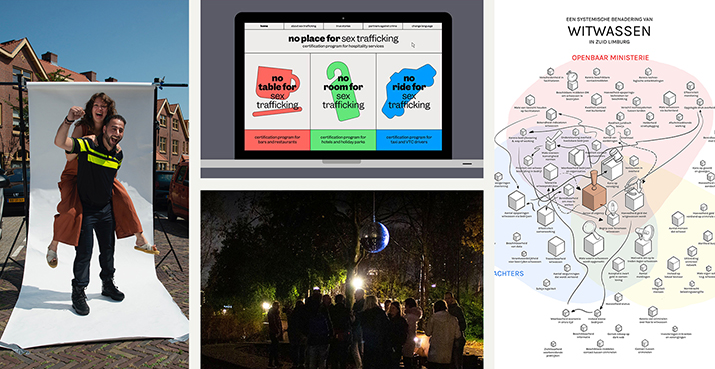

We aimed for a varied and contrasting set of cases, as this provides the opportunity to draw out insights into the determinants of outcomes (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). The cases differed in terms of the manifestation and outcomes of the projects, the collaborative form in the project, and the professional background of project members. Although the choice of domain was mainly informed by our consortium partners, the suspected friction between professional practices—on the one hand safety professionals such as police officers, public prosecutors and civil servants, and creative professionals on the other hand—could contribute to drawing out rich insights into challenges in collaborative processes, and how they are mitigated through design. While we aimed for a varied set of cases, we did decide to focus only on external designers: working in design agencies or as freelancers. Collaborating with external designers is one of the three major flavours of how design collaborations are organized, next to public sector innovation labs (PSIs) and embedded in-house designers (Kim, 2023). In these cases, external designers were specifically sought for their outsider expertise and novel perspectives to potentially foster synergistic and transformative outcomes. Since the challenges encountered by external professionals may differ from those of creative professionals who are working in-house in a public organization, we decided to only focus on external collaborations. Furthermore, given the focus of the study, the projects involved working on complex social issues (Dorst, 2015; Rittel & Webber, 1973). This led to an eventual set of four cases (see Table 1 & Figure 1).

Table 1. Overview of the selected cases.

| Name | Collaborating partners | Description |

C1 |

National Police, freelance social designer, other designers | Social Design Police is a program in which several neighbourhood police officers are paired with a social designer or artist, to work together for a time as strange friends on an issue introduced by the neighbourhood police officer. The project started from the program managers’ interest in understanding what social design could bring to the world of policing. After several exploratory sessions, the first round of the program was eventually run with seven pairs. In this, the pairs ran their own design research but received process support from the creative managers, i.e., through designed moments or communication. Afterwards, the creative managers wrote a book From the Police With Love to record what had been learned about their own process, and to disseminate the results more widely. A second round with eight pairs has been completed and some of the promising outcomes are currently being implemented in the police organization. |

C2 |

Public Prosecution Service, design agency, design research agency, non-profit organization | No Place for Sex Trafficking is an online platform aimed at preventing sexual exploitation of minors in hotels. It was created during the No Minor Thing Challenge, a social innovation program by OMspaces (a creative meeting space within the Public Prosecution Service) and a non-profit design organization in which several design teams worked simultaneously on parts of the problem of sexual exploitation of minors. The project was a collaboration between several creative partners, with a design research agency guiding the research and reframing of the issue, so that the design teams could start their own project quickly. One of the teams, a graphic design agency developed an online platform. The platform offers e-learning training for employees of participating companies in the hospitality sector and teaches them to recognise the signs of sexual exploitation. With 60% participation by staff, a company receives a certificate and promotional materials. In collaboration with OMspaces, after previous grants from the Public Prosecution Service itself and the Ministry of Justice and Security, a partner is now being sought where the platform can be structurally hosted. |

C3 |

Public Prosecution Service, design lab in university | Systemic Design & Money Laundering was a project in which a design lab in a technical university collaborated with the Public Prosecution Service’s innovation lab. The project was initiated by the interest of the innovation lab in what a systemic approach could mean for the Public Prosecution Service. In this project, design researchers investigated how such a systemic approach to the complex problem of money laundering could be of value to the Public Prosecution Service—both for their way of working and the problem of money laundering itself. This project provided a systemic view of the issue and several ideas for concrete products or services to counter money laundering. Some of these innovations fall outside the traditional role view of the Public Prosecution Service. Based on this project, several attempts were made to set up larger research projects, and to develop some of the innovations, but due to lack of momentum and capacity from both parties, little has been implemented. |

C4 |

Municipality of Rotterdam, small design agency, freelance designer | The Night Club is a series of interventions in public space intended to reshape the relationship between residents and all relevant professionals working in the neighbourhood. The Night Club originated in a neighbourhood in the South of Rotterdam, during a project to accelerate energy transition by better understanding the perceptions of neighbourhood residents around this topic. During the research, the designers discovered that there was an underlying sense of insecurity in the neighbourhood and low social cohesion, and that both were perceived as important in residents’ daily lives. Therefore, they developed the Night Club, a neighbourhood intervention focusing on meeting strangers in the dark like in a nightclub. By doing so, they aimed to create trust between people, and between residents, professionals, and authorities—and thus more safety in the neighbourhood. After completing the project, the designers continued with a guerrilla movement started by the municipality in this neighbourhood, with the help of a grant from the Dutch Creative Industries Fund. After successfully carrying out several interventions in the neighbourhood, the initiators went on to develop The Night Club Academy, in which the (social design) ideas of The Night Club would be conveyed to new groups of officials and professionals at several municipalities, and for other complex issues in organizations. |

Figure 1. Visual representations of the four case studies. Clockwise from left: Social Design Police (C1, source: socialdesignpolitie.nl), No Place For Sex Trafficking (C2, source: what-the.studio), Systemic Design & Money Laundering (C3, source: Systemic Design Lab), The Night Club (C4, source: denachtclub.com)

Data Collection and Analysis

We conducted 16 semi-structured, retrospective interviews (see Table 2 and Appendix 1 for the interview protocol) that took place 1-2 years after the collaboration had started, and at least one project had been concluded. To obtain various and complementary perspectives on collaboration, we interviewed 4-5 participants per case. In two instances, participants were interviewed as a duo since they collaborated closely. In addition to the interviews, we collected project documentation such as project plans, grant proposals, quotations, and reports.

Table 2. Overview of interviewed participants.

| Case | # | Role/Job title | Organization/division | Role in the project |

| C1 | P1a,c | Creative manager | National Police | Initiated the project, designed the program and provided process support to the pairs of designers and police officers |

| C1 | P2a | Creative manager | National Police | Initiated the project, designed the program and provided process support to the pairs of designers and police officers |

| C1 | P3 | Portfolio manager | National Police | Responsible for a program that aims to develop and future-proof community policing. Commissioned the project as part of that program. |

| C1 | P4 | Social designer | Freelance | Participated as one of the designers in the program, collaborating with a neighbourhood police officer (P5). |

| C1 | P5 | Police officer | Local police region | Participated as one of the police officers in the program, collaborating with a social designer (P4) |

| C2 | P6c | Program manager | Public Prosecution Service / Creative meeting space | Initiated the program, functioning as the linking pin between the organization and the designers. Contributed to the implementation of promising end results |

| C2 | P7 | Designer | Design agency | Designed the concept of the online platform, and led the process of turning the concept into an actual service |

| C2 | P8 | Design researcher | Design/research agency | Performed the first phase research activities to reframe the problem into several design briefs |

| C2 | P9 | Program manager | Non-profit organization | Organized the social innovation program in which the online platform was developed |

| C3 | P10 | Program manager | Public Prosecution Service / Innovation lab | Responsible for the innovation lab, commissioned the project. |

| C3 | P!1 | Innovation manager | Public Prosecution Service / Innovation lab | Participated in the project as a team member, developing the vision and ideas. |

| C3 | P12 | Prosecutor | Public Prosecution Service / Local district | Participated in the project as issue owner, and was involved in a related student project |

| C3 | P13 | Senior design researcher | Design lab university | Facilitated workshops and played an advisory role in the project |

| C3 | P14 | Junior design researcher | Design lab university | Performed most of the design and research activities in the project. |

| C4 | P15b,c | Designer | Design agency | Initiated the project as a contractor, designed and performed the interventions, responsible for the continuation of the initiative |

| C4 | P16b,c | Designer | Freelance | Initiated the project as a contractor, designed and performed the interventions, responsible for the continuation of the initiative |

| C4 | P17* | Strategic advisor | Municipality / Urban management | Involved (in a later stage) as a collaborating partner, functioning as a linking pin between the organization and the designers |

| C4 | P18 | Account holder | Municipality / Security neighbourhood | Participated in some of the performed interventions, involved for professional perspective |

Note: a,b Participants interviewed as a duo, given that they closely collaborated; c Participants interviewed ~1 year later to reflect on the interim outcomes of the multiple case study.

Before the interview, participants were (digitally) asked to provide informed consent and to review project materials to refresh their memories of the project. The interviews lasted between 1 and 1.5 hours. After introducing themselves and their role in the organization, participants were first asked to describe their account of how the project was initiated, what their expectations were, and how the project was executed, after which we discussed the quality of the project outcomes. We started by asking open questions that allowed participants to verbalise their own experiences, after which we asked the participants semi-structured questions on specific topics, such as relationships between team members, dealing with setbacks, role definitions, internal and external communication, and the role of external actors.

Interview recordings were anonymised, fully transcribed, and analysed using an inductive approach. The first coding round identified challenges, which were grouped into broader themes. In the second coding round, we shifted our focus to design practices that might enable implementation. We excluded challenges irrelevant to our research when they are not addressable through design practice (e.g., infrastructural challenges coming from the tendering process). As our research aim was to identify emergent implementation practices, we mapped the relationship between challenges and design practices, thereby identifying three complexes of practices (Schatzki, 2019; Shove et al., 2012)—interconnected composite practices that exhibit some co-dependence in terms of sequence and synchronisation.

Finally, we discussed the initial themes with key participants in the cases during four one-hour reflection sessions. This helped to enrich our analysis, validate interpretations of results with participants to increase reliability, and to stay up to date with developments in the project. Only in the case of Systemic Design & Money Laundering (C3), we were not able to organize a reflection session.

Findings: Implementation Challenges, Design Practices, and Tensions

As our analysis revealed both challenges to implementation and emergent design practices that aimed to address these challenges, we will first present these, drawing on examples and illustrative quotes from the cases. With this, we build towards the tensions that characterise implementation challenges.

Implementation Challenges

Through analysis of the cases, we identified several challenges to implementation in collaborations between designers and public sector organizations. These challenges manifest across three distinct but interrelated focal areas, each representing different scales of complexity that design initiatives navigate:

- Initiative level: The immediate collaboration space where different professional practices directly intersect through project work. This encompasses the day-to-day interactions between designers and public sector professionals as they collaborate.

- Organization level: The broader organizational environment with its formal practices, processes, and structures. This includes paying attention to existing hierarchies, procedures, and resource allocation mechanisms that shape how outcomes can be implemented.

- System level: The macro context of the complex issue or societal challenge being addressed, often involving multiple interconnected actors, organizations, and wider systems (external to the collaboration). This level deals with aiming to address the complexity of societal challenges rather than developing quick fixes.

Initiative-Level Challenges

These challenges emerge from the immediate context of the design initiative—the core collaborative space where the main actors involved collaborate on a regular basis, and as such, different professional practices, mindsets, and cultures intersect. Initiatives often span multiple consecutive projects and interventions over time, creating a distinct sphere of activity within but somewhat separate from the broader organization with which they collaborate.

The initiative level is characterised by intensive interactions between diverse professional groups trying to work together while navigating different institutional logics, professional identities, and ways of working. Our analysis of the cases revealed three challenges at this level:

- Cross-disciplinary friction: Given the collaborations between safety professionals and creative professionals studied, collaborating often came with crossing disciplinary, positional, and cultural boundaries between team members. For instance, for a police officer, the term intervention may mean the use of violence, whereas for a designer, it may mean developing a product or a service.

- Maintaining momentum: Another significant challenge was maintaining momentum and engagement over longer project timelines, particularly given competing priorities:

I showed that to my colleagues, and that really motivated them to start doing it themselves. [That sticks to some extent,] but we also quickly get caught up in day-to-day urgencies—the busyness, the hecticness. (P5, police officer)

- Value translation: A challenge across cases was effectively translating and demonstrating the value of design initiatives. While organizations favoured quantifiable outcomes, design initiatives often generated different forms of value—such as new ways of thinking or enhanced relationships. In Social Design Police (C1), this manifested in different expectations about what constituted valuable outcomes, such as:

Social Design Police was not about implementing 30 new working methods in neighbourhoods... our expectation was to answer the two main questions: can neighbourhood police officers learn from social designers? And can we, as police, discover other—possibly more meaningful—ways of working by collaborating with social designers? (P1, creative manager)

Organization-Level Challenges

These challenges emerge from the broader organizational context within which the collaborations operate. Organization-level challenges reflect the organizational structures, processes, and hierarchies that shape how design outcomes can be implemented. Unlike initiative-level challenges, which focus on immediate collaborative interactions, organization-level challenges concern how design initiatives interface with established organizational systems and practices over time.

The organization level is characterised by navigating formal rules and processes whilst attempting to embed design outcomes into existing structures. Our analysis of the cases revealed three key challenges at this level:

- Organizational integration: A major challenge was how initiatives could go beyond experimental niches by embedding and integrating outcomes within existing organizational structures, processes, and ways of working. Design initiatives often were initiated in innovation units or special programs at the periphery of organizations, making it difficult to integrate outcomes into organizational practices later. For instance, The Night Club (C4) developed novel participatory practices that had no clear connection to existing participation structures within the municipality.

- Engaging middle management: While engagement from top-level decision makers could often be sparked, engaging middle management proved consistently challenging (evident across all cases, particularly C3, C4). One participant described this as:

That is also the layer that is quite difficult to reach, with whom this may not always end up so easily (...) They just ignore it I always have the feeling. They are like: ‘let them play outside, that’s fine. We’re not necessarily against it, but we’re not really going to do anything with it either’. (P17, strategic advisor)

This disengagement manifested not through active resistance but through passive non-participation. This was evidenced in our interviews as we asked participants to connect us to people who were critical of their project (see appendix, question 12.4), a question which they could not answer. They suggested that others in the organization often ignore it rather than actively resist or voice their concerns.

- Sustainable resources: While interviewees commonly, often as the first thing, cited funding constraints as the main barrier to progress, our cases reveal this as perhaps a convenient explanation for stalled initiatives. Nonetheless, securing long-term resources remains a challenge. Public sector organizations control significant budgets, yet these remain bound by annual cycles and departmental allocations that conflict with the flexible, iterative nature of design work:

Public organizations handle large budgets, but these are tied to annual budgets, results, or departments... People often say, “we can manage it this year, but I can’t make any promises about next year.” (P17, strategic advisor)

This structural misalignment shows through practical constraints—from procurement barriers requiring formal tendering processes for larger budgets to resource limitations that force creative professionals to work with restricted time allocations.

System-Level Challenges

These challenges emerge from the ambition to develop appropriate responses to the complex and systemic nature of the problem being addressed. System-level challenges relate to the macro context of the societal issues that design initiatives aim to address, often involving multiple interconnected actors, organizations, and wider systems that extend beyond the immediate collaboration.

The system level is characterised by the difficulty of addressing underlying systemic conditions whilst working within organizationally bounded projects. These challenges emerge from the ambition to develop appropriate responses to the complex and systemic nature of the problem being addressed.

- Reframing system boundaries beyond mandate: In these cases, the design process was impact-driven: the complex problem guided design activities, e.g., reframing of the problem expanded relevant actors and altered the (potential) role of the organization in the problem. This proved challenging—especially in the safety and security domain—as organizations operate as a chain, where individual organizations focus on their specific responsibilities, such as investigation or prosecution. While organizations could initiate a project, sustaining the outcomes often fell outside their supposed core business, and thus, was not considered legitimate. This was particularly evident in The Night Club (C4), where addressing feelings of safety in the community required working across traditional departmental boundaries and challenging established ways of working, as well as in No Place for Sex Trafficking (C2) where the Public Prosecution Service did not feel that it could legitimately sustain the platform as it aims at prevention rather than contribute to prosecution.

- Involving various actor constellations: Involving and coordinating diverse actor networks across system boundaries proved consistently challenging (strongly present in C2, C4). In impact-driven design processes, outcomes are emergent, meaning that key actors often became apparent only when interventions were being developed, as No Place for Sex Trafficking (C2) required, amongst others, coordinating across hospitality businesses, law enforcement, and support services.

When starting a design process on sexual exploitation of minors, you have no idea where you will end up. Organizational advisors say you need to involve the right people from the start, but it is hard to know who those people are. You cannot predict that [the designers would eventually propose] making a beer brand, a platform for a hotel, or putting educational material in tampon boxes. Involving too many different stakeholders at the start doesn’t work and influences the design process. With complex problems, you cannot arrange everything at the start because you do not know what will come out of it. (P6, program manager)

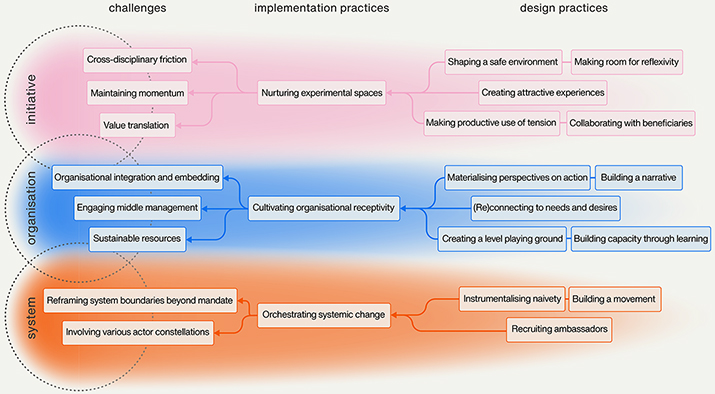

Design Practices

Our analysis revealed 13 design practices that contributed to addressing these implementation challenges. We arrived at these practices by closely examining the relationships between challenges and asking the question: How did the designers in these projects deal with these challenges? Additionally, these practices can be clustered along the previously identified levels (i.e., initiative, organization, system), resulting in three emergent implementation practice complexes (Figure 2). These are: Nurturing experimental spaces, cultivating organizational receptivity, and orchestrating systemic change. An overview of all design practices and examples from the cases can be found in Appendix 2.

Figure 2. Overview of the challenges, emergent implementation practices, and design practices along the three levels.

1. Nurturing Experimental Spaces

The first emergent implementation practice—nurturing experimental spaces—primarily addresses initiative-level challenges by creating conditions that enable productive collaboration between designers and public sector professionals. This practice recognises that meaningful experimentation requires attention to both the physical and relational aspects of collaborative spaces.

Social Design Police (C1) demonstrates how multiple design practices combine to create the conditions for experimentation. The program deliberately employed shaping a safe environment through interventions such as carefully selected venues to meet, a creative learning journal called Vreemde Vrienden Boekje2 (Figure 3, right), and other crafted moments of communication. This reduced performance anxiety and fostered psychological safety for participants in the program.

Figure 3. Role of formgiving and materialisation in nurturing experimental spaces. Left: The Night Club used wooden installations and neon lights to attract and engage visitors (source: denachtclub.com). Right: Social Design Police designed a creative learning journal to structure and shape moments of reflection (source: From the Police With Love publication).

On the outside, it seems to be very much about social design, but actually we wanted to create a setting, a context, a climate where uncertainty is allowed to be, where you can be yourself, where you can learn new things, where it’s not about instructions [as is common within the police organization], but about inspiration. (P1, creative manager)

Rather than trying to eliminate tensions, designers engaged in making productive use of tension and friction through the concept of ‘strange friends’—explicitly framing differences between police officers and designers as opportunities for mutual learning. As one designer reflected:

By the frame ‘strange friends’ I came in differently at the police, as a friend of the police officer. It wasn’t that I was the expert and [police officer] the spectator. We were both disrupted, and both had to let go of what we already knew. (Social designer in ‘From the Police With Love’ publication, p. 33)

In The Night Club (C4), designers combined creating attractive experiences with shaping a safe environment to transform public spaces into intimate settings for conversation. They used distinctive material elements—e.g. disco balls in trees, neon lighting, and silent disco headphones (Figure 3, left)—to create unexpected interventions which signalled that something unusual was happening. As one designer noted:

The other thing that attracts people is [its material form]: The Night Club, it’s an exciting thing, that you quickly get it, but also don’t quite get it. Because what exactly happens in that darkness? I see those chairs, I see that disco ball, but what does it mean, what is that neon light doing there? It’s something that sparks curiosity. (P15, social designer)

The designers also engaged in making room for reflexivity throughout the process. This reflexive practice enabled participants to process experiences and articulate the value of collaborative work from their positional point of view. In The Night Club (C4), as one designer explained,

Really that struggle which is very different in such a team. The [program manager] was just concerned with the goals, do our activities contribute to that. The district manager was more concerned with getting the Directorate of Safety on board, because if they don’t move, we’ll keep having problems with that. [...] So you have to look for some kind of space where you can express this to each other. But you can’t do that all the time, because then you have very long sessions. (P15, social designer)

Collaborating with beneficiaries was central to both initiatives. The Night Club (C4) co-produced events with residents and officials from various organizations in the neighbourhood, having them collectively determine topics and locations as well as organize the events. This collaborative approach ensured the initiative remained relevant to community needs and generated momentum.

Each time we took steps before a Night Club. These were about what’s happening at the moment. What’s happening with you? What’s happening in the neighbourhood, what are you picking up, what are you hearing? And what’s going on in residents’ lives? And then an idea would emerge for how to organize a Night Club around that, and by paying attention to what they’re struggling with at that moment […] really co-designing those questions. (P15, social designer)

2. Cultivating Organizational Receptivity

The second emergent implementation practice—cultivating organizational receptivity—primarily addresses organization-level challenges by creating conditions that enable design outcomes to gain traction within existing structures and processes.

In Social Design Police (C1), the creative managers engaged in building a narrative and materialising perspectives on action through careful documentation and reflection on the process. They created a book titled From the Police With Love that captured the project’s process and outcomes, transforming ephemeral experiences and learnings into a tangible artefact that could circulate within the organization and beyond. The program also focused on (re)connecting to needs and desires within the police force, as one creative manager explained:

The Dutch police have the neighbourhood police officer as their unique selling point. And over the years, that has actually been pushed back a bit by systems, by computers, by working information-driven. So, I think [with this project we connected to a] deep desire: [reconnecting] to our intention, working according to the Dutch way of how we as police want to act in society. (P1, creative manager)

Or as put in another reflection in the book, how the initiative addressed deeper organizational needs: “Being able to ‘be yourself’ seems obvious but can often be more complex than it sounds within a systemic organization such as the police force.” (P1 and P2 in From the Police With Love publication, p. 28).

Together, the initial focus on shaping experimentation spaces and personal development of participants also contributed to strengthening the creative manager’s ability to facilitate social innovation processes and match creative professionals to internal actors. This contributed to a more enduring impact by building capacity through learning, in part addressing the challenge of finding sustainable resources by developing alternative ways to continue these social innovation processes in less costly and time-intensive ways.

No Place for Sex Trafficking (C2) showed how materialising perspectives on action through designed artefacts can build organizational receptivity. The high-quality visual execution of the platform and certification program helped communicate the value proposition clearly, right from the first proposal onwards. As one participant noted, “They had already made something that you could see how it would look...very visual, very graphically strong. Moreover, that works, that is received well.” For internal actors and potential external partners, this helped to generate buy-in as the proposition “was fairly small and manageable, practical, applicable, executable. You can simply say yes to it and then you can do it” (P7, program manager).

Creating a level playing ground was evident in how The Night Club (C4) flattened power dynamics through its informal design, encouraging more equitable dialogue between residents and officials in the neighbourhood. In Systemic Design & Money Laundering (C3), particular attention was paid to equitable exchange of ideas in more traditional co-creation activities performed in a hierarchical organization:

And there were some young people there who were with the project for the first time, I suspect they were new to the Public Prosecution Service and therefore did not yet understand very well where they could start pushing and pulling. [...] We often asked them for a reaction first, but then often left their opinions on the surface, because we also felt that the people who had already thought about it a bit more and were a bit deeper in the field could contribute more in terms of content. (P14, junior design researcher)

3. Orchestrating Systemic Change

The third emergent implementation practice—orchestrating systemic change—addresses system-level challenges by creating conditions for design outcomes to influence broader systems and structures beyond the immediate briefing and organizational boundaries. These practices acknowledge that addressing complex societal challenges requires engaging with multiple interconnected systems and actors, whilst remaining grounded in concrete situated initiatives.

In general, Systemic Design & Money Laundering (C3) was concerned with ways to introduce systemic thinking in the Public Prosecution Service. Here—by instrumentalising naivety—a proposed concept on circulating laundered money triggered deeper discussions about systemic approaches to prevention rather than just prosecution.

There was a [concept], which from a criminology point of view, is super naive to think like that. But the funny thing was that we detailed that for a specific group of people and then it started to become very relevant. When we presented this in the final presentation there were indeed a few people who said that that it is very naive. But there was also someone who was like: this is kind of interesting, because the Public Prosecution Service does work under the radar on such a project. However, what makes such a project very difficult is public acceptance, so it may well be a solution but most citizens won’t accept such a solution. (P13, senior design researcher)

This led to, as another participant observed, the main impact of the project being that it revealed the role of the organization and its practices:

Just the fact that prosecutors [through this process] are now saying ‘wow, I see potential in one of these interventions’ and want to act on it is already a win. It shows we’ve done something valuable that makes people think ‘we should try this.’ It’s different, and though we might not fully admit it, we understand our current methods aren’t working well, making people more open to alternative approaches and interventions. (P10, program manager)

In The Night Club (C4), recruiting ambassadors was evident in how participants became enthusiastic and strategic advocates for the initiative. One designer described:

Those have been touched by something that makes them say: ‘I want this to stay’, and they work hard for that. At the last Night Club a [participating civil servant] called the municipal secretary [i.e., highest civil servant in the municipality] to say that we weren’t getting power for the headphones. Really, I mean, you don’t normally go and call the municipal secretary for that. But just because she really thought this just has to happen, because this is for our residents. That kind of enthusiasm I think, is just to push things through that they would normally approach differently, more cautiously. (P15, designer)

Finally, it showed strategically building a movement by turning The Night Club into a Night Club Academy after successfully conducting several neighbourhood events. This program taught social design approaches to professionals across multiple municipalities—prioritising capacity building and network formation over continuing the initiative in the original neighbourhood.

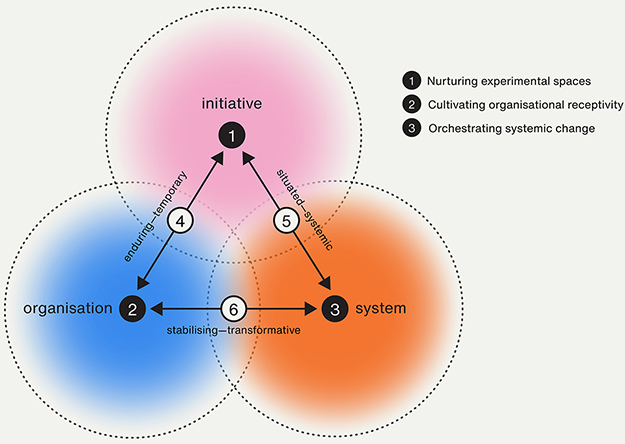

Towards A Tension-Driven Approach to Implementation

So far, our analysis has revealed implementation challenges that manifest across three levels (i.e., initiative, organization, system) and three practice complexes (Schatzki, 2019; Shove et al., 2012) that involve 13 design practices to help address these challenges. Through discussions among co-authors on how the challenges, levels, and design practices are related, we identified a complex dynamic characterised by tensions that link the three levels and the design practices therein. We found that, while these areas can be viewed as nested levels (as shown in Figure 2), they also represent distinct areas of attention that must be balanced throughout the implementation process. Furthermore, focusing exclusively on one area can undermine efforts in others. For instance, prioritising experimentation at the initiative level without considering organizational structures may generate innovative ideas with limited pathways to implementation.

Consequently, the interaction between these focal areas produces three key tensions that practitioners must navigate when implementing design outcomes in public sector contexts: temporary-enduring, situated-systemic, and stabilizing-transformative (Figure 4). The tensions emerge precisely because implementation is not a linear process but rather a continuous practice that requires simultaneous attention to different focal areas, which require active negotiation.

Figure 4. Tensions between implementation practices. The framework illustrates how adapting to three focal areas (initiative, organization, system) through the three emergent implementation practices (1, 2, 3) generates three tensions that must be navigated when implementing design outcomes, (4) temporary–enduring, (5) situated–systemic, (6) stabilising–transformative.

In the following sections, we describe each tension in detail, drawing (where possible) on illustrative examples from our cases that demonstrate approaches to navigating these tensions productively.

4. Temporary–Enduring Tension

The tension between temporary and enduring elements manifests in how design initiatives interface with organizational structures. Whilst temporary spaces enable experimentation and the development of novel approaches, affecting organizational structures leads to an enduring impact.

In the cases, projects were typically positioned at the organizational periphery—within innovation programs (Social Design Police, No Place for Sex Trafficking), or innovation units (The Night Club, Systemic Design & Money Laundering). These arrangements reflect places where external designers commonly operate in the public sector. Starting projects away from organizational structures helped to avoid bureaucratic obstacles, but this detachment complicated later integration into existing structures—ultimately hindering structural change. For example, No Place for Sex Trafficking (C2) had to find a new host organization as the Public Prosecution Service could not long-term sustain the platform as it did not contribute to their core business.

Similarly, The Night Club (C4) developed novel participatory practices disconnected from existing participation structures in the municipality. However, here we see an initial example of deliberate translation mechanisms between experimental spaces and the wider organization. Here, The Breakfast Club (Figure 5) emerged specifically to convert the rich, qualitative experiences obtained at night during a nightclub event into actionable insights for organizational actors.

Figure 5. The Breakfast Club as a translation mechanism between nighttime lived experiences and daytime organizational reality. The Breakfast Club was specifically designed to bring rich qualitative experiences from Night Club sessions into actionable insights for organizational actors. Municipal representatives who had not participated in night sessions were invited to engage with authentic stories from residents. (source: denachtclub.com)

And then in that search for how to do that, how to translate the content of the conversations into what we can do with what we discuss in the night? Can we get to work with it during the day? And that’s when the Breakfast Club was born. And that was really a form to translate those stories, questions, needs and fears that people had into what we can do if we are going to work on it anyway. (P17, strategic advisor)

This intervention aimed to address the disconnect between the intimate experiences created in the Night Club sessions and the more structured, outcome-oriented processes of municipal departments. The Breakfast Club was deliberately designed as a translation space, where representatives from various municipal departments—who had not previously participated in the night sessions—were invited.

We really invited other people who until then weren’t involved with the Night Club at all. And who suddenly got acquainted with those real stories of real people, as they would normally always sit behind their desk in the ‘system world’. (P17, strategic advisor)

This example illustrates how design practices can leverage the tension between temporary interventions and enduring structures. Rather than attempting to integrate the Night Club directly into municipal systems—which might have diminished its distinctive qualities—the designers created a deliberate translation space that protected the integrity of both worlds while facilitating productive exchange between them.

5. Situated–Systemic Tension

This tension emerges between situated engagement within a specific context and attention to broader systems. Situated engagement involves a deep understanding of local relationships, meanings, and ways of working, as it foregrounds the contextual knowledge and lived experience that make interventions meaningful for specific groups of professionals or communities. However, systems change requires a broader impact than can be achieved through local experimentation alone.

The challenge here is how to stay true to localised and situated understanding—and the individuals and communities who contributed to that understanding—whilst simultaneously creating interventions that can achieve meaningful systemic impact. Pursuing a bigger impact carries the risk of leaving engaged actors behind, potentially generating participation fatigue amongst those who contributed significantly to initial phases, as they see diminishing connection to later iterations. Conversely, remaining too locally focused may limit an initiative’s ability to address the structural conditions that perpetuate problems across contexts.

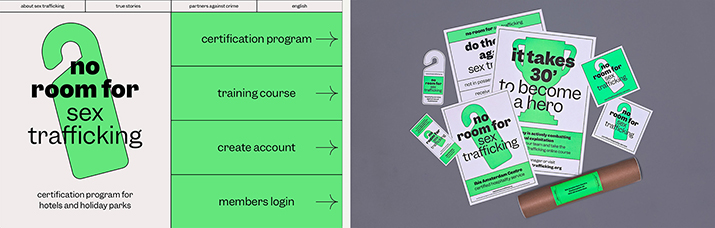

The No Place for Sex Trafficking (C2) case illustrates one way how this tension can be productively leveraged. The designers developed a visually attractive campaign that transformed a difficult and sensitive societal challenge—sexual exploitation of children—into an approachable certification program for the hospitality industry.

The point is, of course, that when you have this huge problem that seems almost unsolvable, if you break it down into smaller problems, suddenly all kinds of possibilities emerge. And that’s exactly what I saw happening with No Place for Sex Trafficking, because it suddenly became specifically relevant and targeted to [the hospitality sector] (P9, program manager)

The high-quality visual execution as well as smart service design choices of the platform (Figure 6) lowered the effort (in comparison to existing in-person trainings), contributing significantly to its adoption across the hospitality sector.

Figure 6. No Place for Sex Trafficking platform interface and certification materials. The digital platform (left) provided a low barrier to have all employees participate in e-learning, while also making specific design choices in their certification program (right) to contribute to its spread. (source: what-the.studio)

When we were still being part of the design challenge of WDCD, what we realised is that there were some similar initiatives from NGOs trying to train employees from the hospitality industry to prevent sex trafficking, but they were like live trainings, 1-on-1. [...] So this is something that doesn’t give any visibility to the problem and, it goes very slowly in a small scale. So we wanted to build on that and make something that would easily reach a lot of people, and which also gives visibility to the problem. (P7, designer)

The project aimed to balance the situated-systemic tension through several mechanisms. First, the initiative deliberately made design choices to create low barriers to entry, tailored to the hospitality sector’s operational realities. Second, the positive approach to certification and the visible markers of being certified implicitly established a norm that encouraged participation from other hotels. The designers were initially concerned about resistance from the hospitality sector, but were pleasantly surprised by their receptiveness:

[At the beginning, we thought] this is going to be probably really hard. They are going to say that yes, sexual exploitation happens, but not in their other companies and so on. […] The response was totally the opposite way. They were super proactive and willing to participate, because the project is free. Then they say, why not? What do I have to lose? No, It’s better they have a tool to prevent a case of sexual exploitation, then if such a situation happens, because then they can get in a bigger trouble. (P7, designer)

This approach demonstrates one way how design can productively navigate the tension between situated engagement and systems perspective—not by choosing one over the other, but by creating interventions that maintain contextual relevance whilst incorporating features that enable broader adoption and visibility. By reframing a complex social problem into manageable, sector-specific actions, the project achieved both situated engagement and systemic reach.

6. Stabilising–Transformative Tension

This tension exists between stabilising organizational practices and enabling transformative change. Public sector organizations require stability to deliver consistent services, yet must also transform their organizational practices, as all cases studied at some point in their process touched upon the entanglement of the partnering organization in the complex societal problem being addressed.

However, while the cases reveal the presence of this tension, they reveal limited evidence of design practices being applied to actively address it. In these cases, we see a pattern that while an initiative is being established (i.e., an initial project is carried out), implementation activities are primarily directed towards nurturing the initiative. Some attention is given to infrastructuring organizational engagement and amplifying impact in the background; however, these are often parallel processes, with one taking priority over the other. For instance, in The Night Club (C4), the situated context and underlying root cause of feelings of unsafety in the neighbourhood took priority over the goals of the program that commissioned the project. This led to outcomes that were considered as foreign objects detached from the organization (cf. Seravalli & Witmer, 2021). In these cases, there is limited evidence of practices that successfully balance stabilisation and transformation, suggesting this as an area requiring further development in implementation practice.

Discussion

Our main aim in this article was to understand how design practices can contribute to the implementation of project outcomes when collaborating with public sector organizations on complex societal challenges. Our research reveals implementation challenges across three distinct but interrelated focal areas—initiative, organization, and system—each requiring different approaches to address effectively. To address these, we identified three emergent implementation practices—nurturing experimental spaces, cultivating organizational receptivity, orchestrating systemic change—which can be seen as so-called complexes (Schatzki, 2019; Shove et al., 2012): interconnected and mutually dependent composite practices which exhibit a certain co-dependence in terms of sequence and synchronisation. As not all of the design practices that were grouped together featured in all the cases, and given the exploratory nature of this study, we cannot establish any causal relationships. Therefore, we refer to these complexes as emergent implementation practices. These design practices provide a complementary perspective to previous research on making public sector organizations more receptive to design approaches (Brinkman et al., 2023; Kim, 2023; Peters, 2020). While organizational receptivity is important, we find that designers can also leverage their distinctive competencies to enable implementation. The design practices we identified demonstrate that the same four competencies valued for addressing complex social issues (van Arkel & Tromp, 2024) can be effectively applied to implementation challenges.

Leveraging Tensions Productively

The cases underscore that implementation practices cannot be viewed as a final stage in a linear process but rather as continuous activities that run concurrently with what would traditionally be seen as designing (i.e., generative practices). This reinforces findings from practice-based research (Boyer et al., 2013; Raviv, 2023) that argues for viewing implementation, or stewardship, not as a final stage in a linear process, but as a continuous process that continues carrying the initiative to the next step, iterating on it, improving it, scaling it, and spreading it (Raviv, 2023).

However, our study also shows that implementation is not simply about performing the identified practices. Adapting to the initiative, organization, and system concurrently introduces inherent tensions that need to be productively handled. Therefore, the primary contribution of our research is a preliminary tension-driven framework for understanding implementation in complex public sector contexts. Rather than just providing a list or taxonomy of challenges, actions, factors or conditions for successful implementation (Brinkman et al., 2023; Pirinen et al., 2022; Yee & White, 2016), our framework highlights the inherent tensions that characterise the implementation process. The three tensions we identified—temporary–enduring, situated–systemic, and stabilising–transformative—capture the complexities involved in turning design ideas into action. With this framework, we highlight the need for critical reflection and adaptation of design practices to the context at hand and propose it as a means to making informed decisions on how to proceed and where to dedicate attention.

We propose working with tensions as they stimulate considering both sides of the coin, instead of proposing a normative orientation. For instance, it may be appropriate in some contexts to privilege temporary engagement over enduring organizational change. Alternatively, the cases reveal that, rather than favouring one pole over another, it may be possible to resolve or creatively leverage all three tensions. For instance, in No Place for Sex Trafficking (C2), designers balanced situated engagement with systemic impact by developing a contextually sensitive yet broadly applicable certification program. Similarly, in The Night Club (C4), the tension between temporary interventions and enduring structures was addressed through the creation of the Breakfast Club as a translation mechanism between experiential events and organizational processes. These examples, however, remain somewhat anecdotal compared to the more robust emergent implementation practices identified, suggesting the need for more systematic methods or tools to support design practitioners in navigating these tensions. Given that tensions are considered to be productive sites of innovation for design (Dorst, 2006; Neuhoff et al., 2022; Ozkaramanli et al., 2016; Tromp & Hekkert, 2019), we see a clear opportunity to develop more systematic approaches for leveraging these tensions.

From Reactive to Strategic Implementation Practices

In design processes, there is often an implicit expectation that a well-designed outcome will naturally lead to implementation and other strategic or field-level changes, which is not a given (Dorst & Watson, 2023). In these cases, significant time and attention were allocated to implementation activities throughout the entire design process, not merely at its conclusion. This continuous maintenance of the collaboration increases the capacity to reorient in case of failure, which also enhances the resilience of the collaboration. Adapting to the context requires greater strategic sensitivity to the organizational context from creative professionals, as well as greater accountability for boundary work as a team, including clients (Brinkman et al., 2024). This includes connecting to people within the organization in a timely manner, or helping the creative professional navigate the organizational context by providing internal organizational knowledge (Seravalli & Witmer, 2021).

Despite identifying promising emergent implementation practices, our findings reveal several significant limitations in how design currently operates in the public sector. The design practices we identified remain largely reactive rather than intentionally strategic. In most cases, designers responded to implementation challenges as they arose, rather than proactively anticipating and addressing them through deliberate planning. This reactivity often makes implementation contingent on serendipitous encounters, personal relationships, or organizational contingencies rather than methodologically sound approaches.

This points to a broader need for systemic design reasoning (van der Bijl-Brouwer et al., 2024), a perspective on systemic design that combines the abductive reasoning logic of design (Dorst, 2011; Roozenburg, 1993) with various systems theories and practices to develop systemic design rationales. Such rationales underlie the intentional aim of design interventions, as intervention is the purposeful action by a human agent to create change (Midgley, 2000). A more sophisticated understanding and application of systemic design rationales may support more deliberate implementation strategies by explicitly connecting the designed artifact, its working principle, and the systemic value or desired effects to be achieved (Goss et al., 2024; van der Bijl-Brouwer et al., 2024). The framework presented in this paper can be valuable when coupled with explicit systemic design reasoning to make strategic choices and articulate the desired effects that should be consolidated through implementation activities.

Limitations and Future Research

Interviewing several different people from each collaboration team affected the type of cases that were eligible to be included in the first place, as only in relatively successful cases were people willing to participate. This may have resulted in identifying a set of challenges that are the most persistent, as relatively easy challenges would have been dealt with without noticing. Furthermore, although all cases come from the Dutch public safety and security sector, the findings may have broader applicability. Specific sectoral characteristics observed—such as strong inter-organizational dependencies (chains), and respective strict adherence to core mandates—exist in other public organizations, but to a lesser extent. This suggests that insights about implementation challenges and practices may transfer to other public sectors, with appropriate consideration of contextual variations in institutional arrangements.

Although we studied the role that the collaboration played in the development and implementation of outcomes, we were only able to retrospectively inquire into these collaborations. This may have given more idealised descriptions of how those collaborations went, as participants may have forgotten certain episodes, or were not even aware of relevant insights in the first place. Thus, longitudinal or ethnographic studies of collaborations could provide valuable in-depth knowledge that could complement our findings in this study.

The practice of outsourcing expertise in public sector organizations by hiring agencies and consultancies is criticised in general (Mazzucato & Collington, 2023), and the outsider relationship between agencies and the organization may affect implementation success (Brinkman et al., 2024; Junginger, 2017). Some of the challenges are the direct result of our focus on collaborations between external designers and public organizations. For example, the challenge of reframing system boundaries beyond mandate only results from there being a client to begin with. At the same time, the cases from this study point towards some distinct characteristics external designers can bring. For instance, The Night Club (C4) developed a new perspective on the relation between citizens and the municipality that probably would not have emerged from within the organization, even in the creative unit that they partnered with later. Here, proposing radical alternatives or instrumentalising naivety can be beneficial to question taken-for-granted structures in organizations. And as complex issues often do not have a clear owner or client (Dorst, 2019), taking an issue-driven approach, such as in the case of No Place for Sex Trafficking (C2), can help to nurture initiatives in the space between organizations, which can be connected to later. Further research is required to develop a typology of public design practices, outlining the advantages and disadvantages of different collaborative forms, such as working with external designers, in public sector innovation labs, and with in-house designers. This can contribute to a better understanding of these different approaches, for instance by building on research that identifies various approaches to PSI labs (McGann et al., 2018) or performing comparative analyses between projects of external and in-house designers.

The tension-driven framework proposed in this paper remains preliminary and would benefit from further systematic empirical research and theoretical development. Future studies should investigate how designers and public sector professionals intentionally navigate the identified tensions in practice—particularly through longitudinal case studies—where these tensions were productively leveraged rather than merely managed. This can then contribute to the development of methods and tools that can guide practitioners in addressing each tension strategically, to eventually develop robust implementation practices for navigating these tensions as well.

Conclusion

This article contributes to understanding design’s impact in the public sector when working on complex societal challenges by examining implementation challenges when external designers collaborate with public organizations. Our analysis reveals implementation challenges across three levels (initiative, organization, system) and thirteen design practices. The design practices coalesce into three emergent implementation approaches: nurturing experimental spaces, cultivating organizational receptivity, and orchestrating systemic change.

Moreover, our research reveals that effective implementation requires navigating tensions (temporary-enduring, situated-systemic, and stabilising-transformative) between these levels, thereby viewing the levels as focal areas in implementation work. Our tension-driven framework enables practitioners to make more informed and strategic choices about where to focus their efforts throughout the implementation process. However, current design practices remain largely reactive rather than intentionally strategic, pointing to a need for more deliberate approaches that incorporate systemic design reasoning.

Our findings demonstrate that implementation is not a final stage but a continuous, adaptive practice beginning at the outset of design initiatives, extending previous work on stewardship (Boyer et al., 2013) and continuous implementation (Raviv, 2023)—where the pathway from ideas to change deserves as much attention and effort as the design of interventions themselves.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of our consortium—Tabo Goudswaard, Madelaine Berlis, André Schaminée, and Wim Wensink—for their collaboration, insightful feedback, and joint learning during the research. We are equally grateful to all participants who contributed their time and perspectives during the interviews. We also wish to acknowledge the constructive contributions of two anonymous reviewers and Sofie Dideriksen, whose feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript significantly enhanced the final work. This research was made possible with a KIEM GoCI grant, an initiative of CLICKNL and Regieorgaan SIA.

Endnotes

- 1. Here we take the word ‘project’ in a broad sense, focusing on the execution as well as acquisition, problem formulation, and the continuation and impact after the conclusion of the project.

- 2. Strange Friend Booklet, analogous to a Dutch custom where kids at primary school exchange booklets with a set of pre-formatted sections in which friends, classmates, and even teachers write personal messages, draw pictures, and share information about themselves.

References

- Bailey, J. A. (2021). Governmentality and power in ‘design for government’ in the UK, 2008-2017: An ethnography of an emerging field [Doctoral dissertation, University of Brighton]. https://research.brighton.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/governmentality-and-power-in-design-for-government-in-the-uk-2008

- Bason, C. (2017). Leading public design. Policy Press.

- Bason, C. (2018). Leading public sector innovation 2E: Co-creating for a better society. Policy Press.

- Boyer, B., Cook, J. W., & Steinberg, M. (2013). Legible practises. Helsinki Design Lab.

- Braams, R. B. (2023). Transformative government: A new tradition for the civil service in the era of sustainability transitions [Doctoral dissertation, Utrecht University]. Utrecht University Repository. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/433379

- Brinkman, G., Molenveld, A., Voorberg, W., & van Buuren, A. (2024). Turning rejection into adoption: Enhancing the uptake of externally developed design proposals through boundary spanning. Public Management Review, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2024.2436614