Service Design and Change of Systems:

Human-Centered Approaches to Implementing and Spreading Service Design

Mike C. Lin 1,*, Bobby L. Hughes 1, Mary K. Katica 1, Christi Dining-Zuber 1, and Paul E. Plsek 2

1 Kaiser Permanente- Innovation Consultancy, Oakland, United States of America

2 Paul E. Plsek & Associates, Atlanta, United States of America

This paper provides an ‘on-the-ground’ design case study dealing with the important issue of how to implement and spread service design concepts in large, complex organizations. When implementing a service design concept called Nurse Knowledge Exchange (NKE and NKEplus) with the frontline staff at our hospitals, our design team explored the value of converging basic change management theories with our existing design practice. Using change management theories to guide us as a design team during the implementation process resulted in a redesign of our implementation methods and inspired a more human-centered approach to spreading our service design concept with the people delivering the service. This paper outlines the implementation challenges we encountered, details how change management principles shifted our methods in implementing our service design, and reports on the value and shortcomings of our approach for the design community to consider in the future.

Keywords – Human-Centered Design, Change Management, Healthcare, Implementation, Service Design.

Relevance to Design Practice – This case study provides an example of existing theory and literature put into practice. Designers stand to benefit from seeing a role for themselves in helping implement new processes and service designs as well as from developing an understanding of how design practice, when combined with existing change management theory, can create engaging, human-centered ways to roll-out new services and behaviors.

Citation: Lin, M., Hughes, B., Katica, M., Dining-Zuber, C., & Plsek, P. (2011). Service design and change of systems: Human-centered approaches to implementing and spreading service design. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 73-86.

Received November 1, 2010; Accepted April 29, 2011; Published August 15, 2011.

Copyright: © 2011 Lin, Hughes, Katica, Dining-Zuber, & Plsek. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

*Corresponding Author: michael.c.lin@kp.org

Mike C. Lin is a senior design strategist at the Innovation Consultancy at Kaiser Permanente. Keenly interested in the neurological basis for behavior, he started out as a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University. Mike then went on to work at various consumer insight, brand and innovation consultancies. Over the last 10+ years, Mike has contributed his energy and expertise to helping companies like PepsiCo, Diageo, Samsonite, Microsoft, and Royal Caribbean understand their consumers better, and articulating fresh opportunities, platforms and product ideas to better engage and connect with them. In his most recent role at Kaiser Permanente, Mike guides a team of designers and clinicians to develop and implement human-centered solutions aimed at addressing some of the most challenging frontline patient care challenges. Over the last couple of years at the Innovation Consultancy, Mike has been leading the team in exploring how design can be used to motivate and sustain change in a health care setting.

Bobby L. Hughes is a senior designer and innovation consultant with a passion for creating engaging, playful experiences that promote learning and cultivate lasting, positive change. Prior to his experience as Lead Designer with Kaiser Permanente’s Innovation Consultancy, Bobby served as a product designer and innovation consultant at IDEO, a design and consulting firm based in Palo Alto, CA. He is a part-time lecturer at the HassoPlatner Institute of Design at Stanford University (a.k.a. the d.school), and has consulted a variety of organizations including Nike, Smith Sport Optics, Walmart, and Teach for America, bringing a design approach to tackling complex systemic problems. Bobby holds a BS in Physics from the University of Washington and an MS in Engineering/Product Design from Stanford University.

Mary K. Katica is a senior innovation and design analyst with Kaiser Permanente’s Innovation Consultancy. A creative problem solver, Mary has focused on bringing human centered design to healthcare – working in her previous role with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center to use design thinking to explore home healthcare opportunities. In her current role with Kaiser Permanente, Mary thoughtfully ideates and creates solutions to improve the care experience. Mary holds a BFA in Industrial Design from Carnegie Mellon University.

Christi Dining-Zuber is a nurse with a passion for design. She is the director of the Innovation Consultancy at Kaiser Permanente. Christi has been with Kaiser Permanente since 2001, in roles that have encompassed finance, strategy, facilities design, and her current position in the Innovation Consultancy which she began to build in 2003. In her innovation and design work, Christi has partnered with IDEO to learn and internalize a human centered design methodology into Kaiser Permanente. Christi and her team have spent thousands of hours of time shadowing, conducting ethnographic observations in clinics, hospitals and patient’s homes, and field testing ideas in the front lines of healthcare. Christi has a master’s degree in Health Administration and a Bachelor of Science in Nursing from the University of Oklahoma.

Paul E. Plsek is an internationally recognized consultant on service innovation and change management in complex organizations. A systems engineer, former director of corporate quality planning at AT&T, and developer of the concept of DirectedCreativity, his work can be described as “helping organizations think better.” Clients have included the Ministries of Health in England and Norway, Kaiser Permanente, the Veterans’ Health Administration, and the Mayo Clinic. He is the Chair for Innovation at the Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle; the Director of the Academy for Large-Scale Change in the UK; a former senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement; a research investigator with the Vermont-Oxford Network; and a popular conference speaker. Paul is the author or coauthor of dozens of journal articles and seven books. He holds an MS in systems engineering from the Polytechnic Institute of New York (Brooklyn).

Introduction

Much has been published, in academic literature as well as practitioners’ recounts in business publications, about organizations employing human-centered design and design thinking to drive service innovation (Bitner, 1992; Holmlid & Evenson, 2006; IDEO, 2008; Morelli, 2002; Shostack, 1984). As an in-house group that has been practicing the application of design thinking and human-centered methods to deliver innovations in frontline hospital operations for seven years, our team has found that, in practice, implementing service design changes across a complex organization poses significant challenges design methods alone sometimes fail to address. This paper poses the question: Can design thinking be constructively coupled with change management thinking to help practitioners, in addition to helping design the innovations themselves, also design better implementation of service innovation?

As designers, we are trained to understand the varied and complex needs of people, and then to design solutions and services that meet those needs. Typically, we think of optimizing the encounter so that it primarily meets the needs of the person receiving the service – the “customer.” This often requires a fundamental change in the behavior of the person providing the service. While we of course take into account the needs of the service providers in developing the design, we typically rely on approaches such as training, information technology (IT) supports, and changes to formal job descriptions to bring about this behavior change.

The common challenges associated with implementing design in a health care setting have been noted by Bate and Robert (2007). They specifically point out that because the service providers are strong, autonomous professionals (e.g., doctors and nurses), there is a heightened need to design the process to foster personal ownership and create a more immersive experience while making implementation fun, stimulating, and interactive. The topic of ‘spread’ of service innovations is also well-studied in health care, revealing key themes of innovation attributes that effectively ‘predict’ successful adoption and spread (Bodenheimer, 2007); among these are: fit with the culture and values of the majority of potential adopters, degree of involvement of the adopters from the start, and listening to and addressing the ideas and needs of the laggards rather than dismissing them as heel-dragging. The extensive systematic literature review on spread of innovation in healthcare conducted by Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, and Kyriakidou (2004) also draws attention to the importance of a cluster of factors regarding the needs, motivation, values, learning styles, social networks, and peer influencers of professionals that must be taken into account during design and implementation. Much is also known about best practices in health care process improvement, specifically the importance of plan, do, study and act (PDSA) cycles of change involving front-line professional staff (Shewhart, 1931), as reflected by wide-adoption of the Model for Improvement (Langley et al., 1996) by health care organizations and by our own organization’s Rapid Improvement Method (Schilling, 2009).

We are not the first to suggest linking design and change management thinking. There is a small, but growing, body of literature examining the value of such a cross-discipline approach. For example, Van Aken (2007) describes a ‘design science’ approach to organizational development that aligns business and human values, and underscores the importance of (1) designing minimum specifications for the process (formal, made by change agents), while enabling (2) a “second redesign” (informal, made by direct stakeholders) that allows those providing the service to customize what finally gets implemented. Van Aken concludes that for effective change, it is essential to treat the first design as the means rather than the end, and to focus on creating the conditions and learning that enables the second redesign to occur. Likewise, in looking at human-centered service design and organizational change, Junginger and Sangiorgi (2009) encourage designers to move from playing the role of ‘directors’ in the process, to playing the role of ‘enablers’, ‘facilitators’ and ‘connectors’ in a participatory design process that iteratively ‘builds capacities from within.’

Despite this, there are very few practitioner accounts reflecting tangible practices to implement the above principles. Here, through a project called Nurse Knowledge Exchange (NKE and NKEplus), we provide an ‘on-the-ground’ case study with practice-oriented insights into how to leverage design methods in a multidisciplinary way that integrates change management methods to impact the implementation and spread of service design. Given the specifics of the challenges we encountered during the implementation of NKE and NKEplus at our hospitals, we detail three key insights from change management that impacted our approach -- the Concerns-Based Model (Hord, Rutherford, Luling-Austin, & Hall, 1987), Force-Field Model and Three-Stage Process for Change (Lewin, 1951), and the concept of thinking about managing change as a series of conversations (Ford, 1999). We share how these change management concepts were applied with design-centric methods to create a more humanistic and engaging service design implementation process, and we discuss the value of such a multi-disciplinary approach, as well as the shortcomings and limitations we discovered.

Methodology

NKEplus was developed from April to September of 2009 with four medical-surgical units in two Northern California Kaiser Permanente hospitals (Sacramento and Santa Clara) and about ten design team members from Kaiser Permanente’s Innovation Consultancy. The design team spent more than 200 hours working in the field, observing, shadowing, and interviewing frontline staff from April to May 2009. From June to September 2009, ideas and solutions were gathered during more than 2,000 hours of piloting and field-testing from a multi-disciplinary group of 150 participants. Roles represented include: staff nurses, unit assistants, nursing assistants, unit managers, educators, charge nurses, discharge planners, and physicians. Ancillary support departments such as pharmacy and environmental services also participated.

After early failures in our first three units, a new implementation approach was needed. From December 2009- March 2010, the final unit participated in what we have called a ‘soft-start implementation approach’ - one that merged change management concepts and human centered design. To understand the impact of the new approach, the design team collected data through five key methods:

- Documentation: Meeting agendas, e-mails, 5,246 photos, and 214 videos from key events.

- Direct observation: Contextual notes and thoughts from events that occurred in real time.

- Physical artifacts: Evidence such as posters, notebooks, and prototypes created by the participants.

- Qualitative interviews: The team held two video-taped, one-hour sessions to debrief the implementation approach: a session with the unit manager and assistant nurse managers and a second session with three RNs involved in the implementation process. The sessions covered both open-ended questions about the process and focused questions aimed at feedback on each of the specific tools and activities used throughout the new approach.

- Process Metrics: Collected a baseline then seven months post-go-live data by auditing 30 RN-Patient interactions per month per pilot unit. The audits tracked the RN adherence to the seven components of NKEplus and how many minutes it took to do each exchange.

The data was then analyzed by sorting the data points into the key activities and tools used. These activities were then measured by the quality of engagement, enthusiasm, and ownership each activity inspired in the participants. This approach facilitated an understanding of whether the ‘soft-start’ approach activities resulted in a better implementation than the initial approach.

Human-Centered Implementation Case Study: NKE and NKEplus

Background

In 2004, we were asked to apply our innovation and design skills to a very complex challenge – nursing communication and knowledge handover. After a great deal of time in the field observing and interviewing, many hours of design sessions, countless iterations of prototypes, and weeks of field testing, a suite of ideas was born which we named Nurse Knowledge Exchange (NKE). The essence of these ideas was to focus on improving the process of information exchange between nurses as they handed off the care of their patients from one shift to another, with a particular emphasis on having this transfer of knowledge occur at the bedside.

This transfer of knowledge occurs in every unit at all 37 of our hospitals, involves all 45,270 staff nurses in our hospital system, and happens three times every 24 hours, 365 days a year. The solutions that were designed as a part of NKE required significant behavioral shifts. At the time, information at shift change was primarily passed from one shift to the next using a tape recording made by the off-going nurse on a recorder in a back break room. Inspired by patient stories around the feeling that hospital units felt like a “Ghost Town” during shift changes (because all of the nurses disappeared to exchange information), the frontline staff wanted to develop a new way to provide a warmer and safer exchange that was more visible to the patients.

Those hospitals involved in co-designing the “new way” developed a process where a face-to-face hand-off would occur between the off-going and on-coming nurse that included the patient at the bedside. As a part of this exchange, the patients’ upcoming plan for the day was also visually captured on the wall. All of these components were very powerful. They had the ability to fundamentally change the interaction not just between nurses, but between nurse and patient as well. As a part of this effort, our team helped to lead the spread of NKE across Kaiser Permanente’s 37 hospitals.

In 2009, many projects and cycles of learning later, our team was looking for opportunities to increase nurse’s time at the patient’s bedside in the hospital. The nurse shift change again surfaced as an opportunity. We saw a significant variation in how the spread, and particularly the sustainability of NKE, had occurred throughout Kaiser Permanente since 2004. Many hospital units were still struggling to get nurses to go to the bedside at shift change, while other units had not only adopted the ideas in NKE but had also improved upon them. Our field observations revealed that there were many reasons nurses were not uniformly going to the bedside at shift change. Some of these were due to competing priorities that would arise during that time period, such as new patients being assigned to them or caring for a patient in pain. Other reasons were less technical and more emotional, such as the nurses not being comfortable at the bedside, feeling as if they were ‘on stage’ during the shift exchange. Other reasons were more fundamental; for example, some nurses didn’t believe that going to the bedside at shift change was important or necessary.

These insights led us to begin co-developing NKEplus with the frontline staff in 2009. Inspired by stories and observations around the disruptions and interruptions that occurred during shift change, the frontline staff focused on creating a suite of solutions to build on the original NKE that better supported the nursing staff around that time.

Early Failures

After the concepts had been co-developed and field-tested with our pilot units, our initial approach to implementation seemed fairly straightforward. We assumed that the units were “bought-in” to the idea of the change associated with NKEplus, so we focused on “know-how,” compliance, consistency, and clarity.

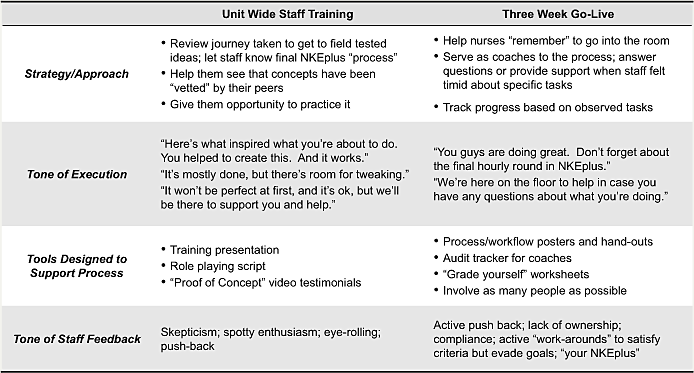

As shown in Table 1, our plan was to train the unit staff on the principles of NKEplus, share stories gathered from observations, review the framework that was developed in detailed design sessions, show the progression of the iterative prototypes, present ‘proof of concept’, and offer opportunities to practice through role playing. As shown in Figure 1a, we presented this information to staff using a traditional lecture format and an on-screen presentation for the first part of our sessions. To build confidence in the concepts that were developed, we emphasized how their hard work had contributed to creating ideas that were “mostly done” but that there were still opportunities to tweak as needed. We felt confident the ideas would be received with enthusiasm.

Table 1. Initial approach to NKEplus implmentation.

To demonstrate how involved the frontline staff had been in developing the ideas and the benefits of these ideas, we produced videos that included testimonials from those who were directly involved in the design. These videos showed nurses standing behind the concepts of NKEplus. We were certain that there was no better endorsement than peer validation.

To help staff engage in and understand the new concepts through kinesthetic learning, we facilitated a role-playing exercise where we provided a sample script (Figure 1b) to direct them in how to perform this new process. This facilitated some playfulness in the training such that we felt we had taken enough measures to cover our bases and that all would go well.

Figure 1. Initial training approach: (a) Training presentation; (b) role-play script for the break-out session.

Surprisingly, our approach to the training resulted in criticism and created skepticism. Those who were less involved or not involved at all quickly criticized the ideas that had been developed by some of their teammates.

As a whole, the unit staff struggled to see the connection of how their peers’ insights and suggestions from shadowing, interviewing, prototyping, and field testing became the final product – largely because it was very difficult for us to include every member of the staff in every step of the rapid development process. Furthermore, our lecture format and written script left little room for staff who had not been involved to provide additional input and ultimately engage and feel ownership of this new process.

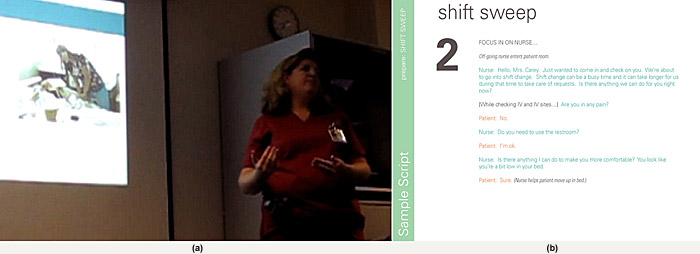

As a part of the three-week go-live process, we set up an around-the clock floor presence to coach nurses and staff on ‘what to do’; provided tips on situational challenges that came up; and tracked progress in terms of the tasks associated with the new workflows. Figure 2 shows a checklist we used to observe how nurses were doing with this new process and to measure, for both their benefit and our own, how well they were adopting the steps we had prescribed. During regular communications with the unit, the tone of the communications at huddle meetings and with individual nurses focused on the rational, problem-based urgency of why we were doing what we were doing (“better patient care”, “safer”).

Figure 2. Tracker used while coaching during initial implementation.

Without having accepted the need for change, our task-focused coaching approach created even stronger push-back to change. In our initial pilot go-lives, we encountered spotty enthusiasm, resistance, and attitudes reflecting lack of ownership and even disinterest. This became evident in the feedback. We heard statements such as “well, we do things differently here” and “you’re not nurses, how is it that you think you know how to do our jobs better.” Observations from members of the team not directly involved in the day-to-day of the implementation revealed “behind-the-scenes” chatter criticizing the idea, as well as “eye-rolling” and “we’re doing it because we have to” sentiments.

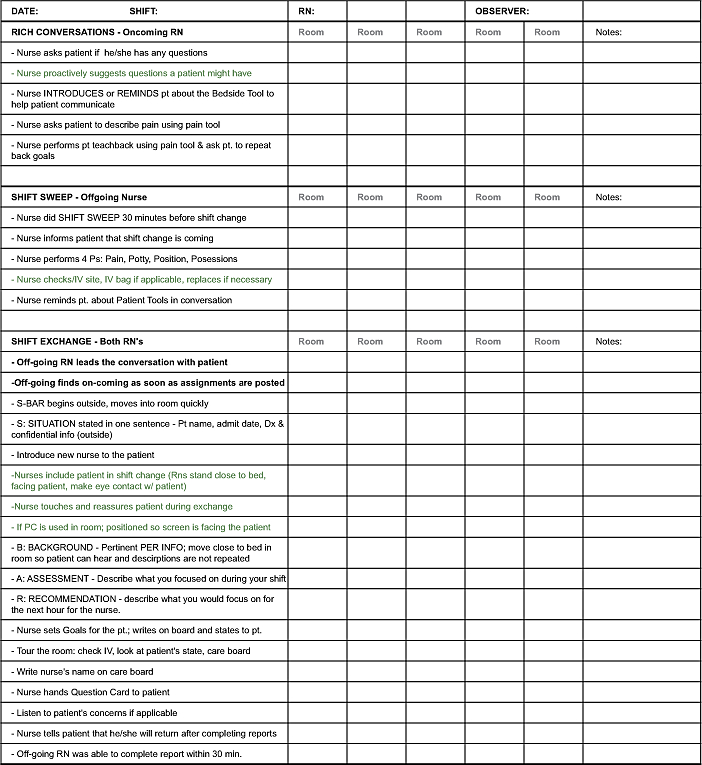

As we collected process metrics around the components of NKEplus, it became evident that our efforts to convince and remind the staff of NKEplus was not a successful and sustaining effort (Table 2). Collectively, we hadn’t realized that what the frontline staff needed wasn’t help in performing the workflows associated with NKEplus. We started suspecting that they didn’t believe in the need for change. As we listened and observed, we realized that they didn’t need coaches. They needed facilitators that could help them see and feel the reasons behind the change.

Table 2. Process metrics from unit with initial implementation approach.

This oversight was reinforced when we met with individuals whose role at Kaiser Permanente is to work on improvement projects. They underscored similar observations from their experience. In their efforts to spread evidence-based best practices they often did not see the same kind of “stickiness” or sustainability that they saw in the pilot sites from which the ideas were born. They attributed this to “not made here” sentiments from those units not involved in original design.

It was clear that our approach to fully engage clinicians in implementing NKEplus had failed.

Fresh Solution: Converging Change Management Insights with Design Practice

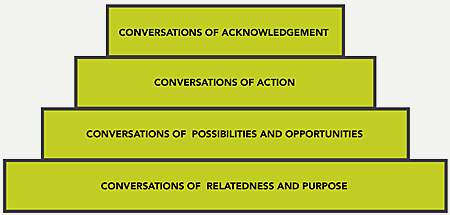

We were frustrated, and the staff members felt the same. We needed new ideas for a fresh approach. Seeking inspiration and help, we were directed to meet with an organizational development consultant at Kaiser Permanente. Upon hearing our stories, we were introduced to a model (see Figure 3) to think about change as a progressive series of conversations.

Figure 3. The cake model for change.

This material is drawn from the work of Landmark Worldwide, LLC and used with permission.

The cake model implies that talking to staff about “what to do” (conversation of action) is only valuable after giving appropriate time and effort to helping them relate to the underlying goals of the action and involving them in seeing a variety of possibilities of how to achieve that goal. Specifically, we were encouraged to spend more time talking about the issues driving the need for change, with special emphasis on whether staff could relate to those issues. Likewise, we were also encouraged to be aware of individuals that made up the collective whole.

The underlying concepts that she introduced us to, as well as the specific points of change management advice that inspired us as a design team, are well-documented principles in change management literature. The Concerns-Based Model (Hord et al., 1987) posits that change is a process, not an event. Furthermore, it presents change as a process that is accomplished by individuals acting on their own concerns. Force-Field Analysis and the Three-Stage Process for Change (Lewin, 1951) describe the importance of the ‘unfreezing’ that is necessary to create change on an organizational level and point out that the need and awareness for change must exceed the restraining and resisting forces that are preventing change. Ford (1999) describes the usefulness of thinking about managing change as a series of conversations and suggests that one can use these conversations to gauge the reality of the change.

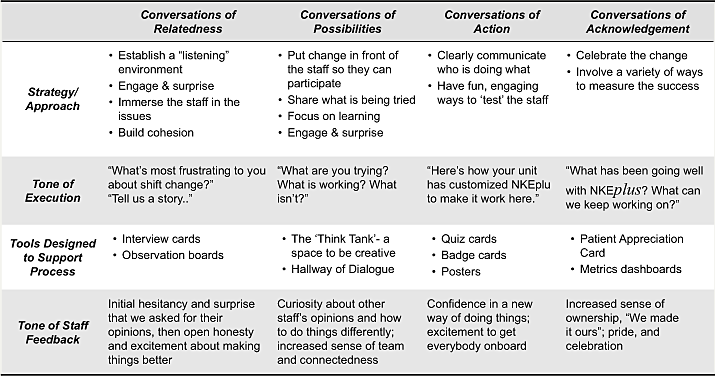

Together, we interpreted these change management principles as an opportunity to design a more human-centered process for implementing NKEplus. We went back to the drawing table and devised a three-week ‘soft-start’ process that would purposefully create conversations and other opportunities for interaction with the service design before implementation. Table 3 describes the approach and provides contrast with the previous approach described in Table 1.

Table 3. Soft-Start approach.

The goal for this ‘soft-start’ was to allow time to focus on more listening and sharing (rather than telling), more “trying on” of ideas and letting people tailor existing solutions for fit with their unit’s demands, and to use design skills to foster more excitement and true engagement.

Design Examples for Building Relatedness

We found that the best way to motivate and prime the team for implementation was to create a strong foundation of shared purpose with the frontline staff. They needed to feel what was happening. We observed that frontline staff is often so accustomed to issues and work-arounds that they don’t see what is happening. They needed to believe in the reasons it is important to change their behavior, understand the common goal, and the role that their individual behavior plays, both in contributing to the challenges and solving them.

A Playful, Engaging Start

To kick off the ‘soft-start’ process, rather than just telling the frontline staff the goals to drive toward, we engaged them and connected with them on an emotional and visceral level first. This is especially valuable in a hierarchical setting, where frontline staff members often have their guards up, where they feel overwhelmed with organizational imperatives, and where there are more messages than people can possibly remember.

To break through, and to create an element of surprise and delight, we created a quick and rough rap video to communicate the goal of increasing nursing time at the bedside with patients. In a matter of days, the team came up with some rhymes and lyrics to capture the background of NKEplus, goals, and potential implications. Our team recorded a soundtrack and filmed one of their own rapping and dancing around on the top floor of the hospital parking garage (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Rap video development: (a) rap lyrics; (b) video still image.

With this video, we set the tone early on that it was safe to be vulnerable and that fun, humor, and creativity are encouraged. When reflecting on the rap video during a debrief session, a RN commented on how it really shifted the tone of NKEplus: “It made me realize this was going to be a fun thing.” Furthermore, the unit staff responded and built on the fun atmosphere by stepping up voluntarily to create a video of their own that celebrated the purpose of NKEplus and their commitment to creating a safer, more consistent shift change.

Establish Open Lines of Communication

After setting an early playful tone, we emphasized transparency and open communication among staff of all levels throughout our initial training session. We were frank in our introductions that this change was about them.

“Let’s be really clear. This is a time for us to really talk about these issues and be very forthright and honest about how you feel. Are these things important to you guys?” – Design Team Facilitator, Kick-Off Session 2/13/2010

“The other thing is if you have reservations, say it now. So that a change can be made or that your reservations can be addressed and dealt with. This is really important” – Assistant Nurse Manager, Kick-Off Session 2/13/2010

“Everyone’s idea has equal value. That’s the whole point of us getting together is to determine what we can do to make it better. It’s not just, we are going to do this because we are told to do it. We are really trying to get away from that dynamic and really try to see what it is like when we all work together to make a change.” – Unit Manager, Kick-Off Session, 2/13/2010

In addition to telling them how important their thoughts and ideas were, we physically set up the room and our training materials to have everyone on the same level conversing as peers. Seating the group in a circle established a feeling of cohesion and open communication. Rather than lecturing with a PowerPoint, we shared communication materials using printed posters mounted on foam-core that could be passed around (Figure 5). This brought the information down to a tangible and approachable level in a way that people could engage with it directly.

Figure 5. Example of how the sessions were set-up to encourage open communication.

First-Hand Immersion

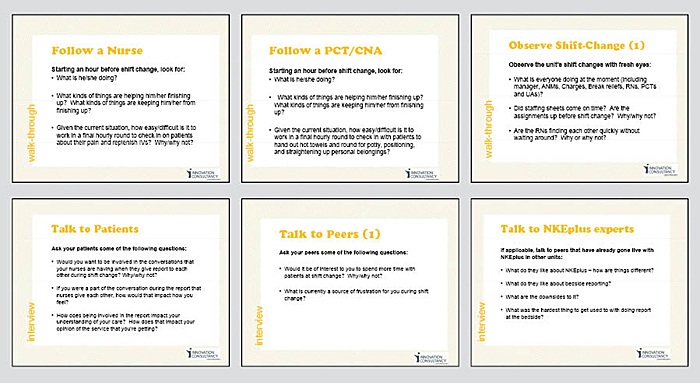

The notion of immersive understanding is common in the early stages of the design process (Bate and Robert, 2007), however our team wanted frontline staff to experience the issues firsthand as a part of the soft-start implementation approach. The RNs needed to have the time to observe and reflect as outsiders because when on-shift, frontline staff are so often dealing with hectic situations that they don’t stop to think about the consequences. Likewise, they often don’t have the opportunity to see how issues manifest for others. As such, we developed observation guides to point staff to problems within the current system that had been uncovered from earlier discovery work and interview cards with specific questions to ask their peers and patients regarding key issues (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Interview cards helped guide the staff to understand the key issues.

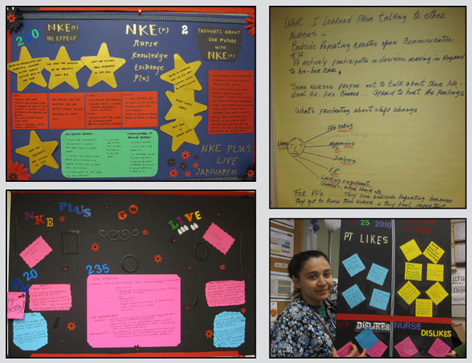

After conducting interviews and observations, we gave the unit staff craft supplies to create boards to communicate what they had learned and to share them with their peers (Figure 7). This provided a visual story that was easy to share with the unit staff, opening up the door for individuals to communicate their accounts with others. This resulted in a more engaged critical mass of people and a stronger sense of cohesive purpose around shift change.

Figure 7. Observation boards helped to facilitate discussion and sharing among the staff.

Peer-to-Peer Story-Sharing, Don’t Just Story-Tell

Storytelling has been touted as a powerful tool in design for communicating and bringing design issues to life in a concrete manner for the design team, the users, and the organization (Erickson, 1995). In our early implementations, we noticed that even though the stories that were retold to others were emotionally charged and true for the original co-designers, new audiences didn’t feel like the stories reflected their own experience. This time around, we would take a very different approach and use our story to prompt their own personal accounts – to “story-share” in a group setting amongst each other, rather than just to rely on our signature story. In the case of NKEplus, we very quickly shared stories about getting late assignments, starting the shift off with patient requests, and being interrupted during shift change. And as we brought these up, the staff members were prompted to share their own stories:

“You have a time crunch. They don’t want you to get overtime and you only have 30 minutes. So, for you to go into the room, and then the patient’s asking you questions. ‘Well, what do you mean about my labs?’ ‘Well, what do you mean about my surgery?’ ‘Oh, that’s what really happened?’ ‘Who said that’ or ‘When is my doctor coming? Are they coming now?’ ‘When am I getting discharged?’ ‘What do I have to do?’ Ughhhh” – RN, 2/13/2010

“Just last Monday, I had a patient. I assessed the patient at 8 o’clock and I noticed the patient had slurred speech, but it was not assessed at shift change because we don’t do [in-room shift change] NKE. I don’t see anything in the notes that the patient had slurred speech. When I called the doctor, the doctor told me it’s not his baseline. So, we had to call rapid response team right away. But, if it was in front of me by the night shift nurse or we found out during the NKE we would be able to determine, at least, if it just happened or it happened last night.” – RN, 2/13/2010

As RNs told their stories, their peers nodded their heads and chimed in, which opened up conversations, allowing us to facilitate discussions of how people felt about each other’s stories on their own units.

This story-sharing approach had two key results: (1) staff felt the issues were much more relevant to them, and (2) it ultimately got the group closer to a shared sense of urgency because unit staff had the opportunity to hear each other speak of their experiences, frustrations, and reflections. This was especially important in creating a sense of cohesion, because “disbelievers” had an opportunity to hear numerous recounts from their peers, rather than us (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Story-sharing during the initial project Kick-Off.

Together, the combination of a playful, engaging start, story-sharing, experiential immersions, and peer-to-peer sharing solidified the emotional bond to the issues and the goals that we lacked in our early implementations. Even those who were resistant to change at this stage of the process were willing to move forward, despite their reservations, because they had heard how important the issues underpinning NKEplus were from their immediate peers. It is important to note that, here, our design team played the role of facilitators to encourage discussions around the issues. Three elements were important during this process: tonality, opportunity to experience the issue, and assets and forums that promoted group sharing.

We knew the unit staff was ready to move on as soon as they naturally started talking about solutions in an engaged way as a unit and not just as a few individuals amongst a group.

Designing to Encourage Conversations around Possibilities

As people started to talk about solutions, we then shifted our attention to creating an environment that fostered a willingness to change, fail, and revise as needed. It was also critical that we engage as many people as possible in discussing solutions. Rather than being directive about what they needed to do, we asked them: What do you think should be done? What are you willing to try? What are you willing to change? If you try something and it doesn’t work, how do you want to change it?

Customizing for Ownership

To encourage the above, we deliberately left the ideas unfinished and rough, allowing the staff to customize the ideas to make them work for them. This might seem counter-intuitive, but at the time, we thought that by giving everyone the opportunity to collectively have a hand in shaping the final finish of the concepts to fit their needs, they would feel a stronger sense of ownership in the final “product.” This is consistent with Van Aken’s findings on providing a formal design with “minimum specs” up front and focusing more effort on the learning associated with the second “informal” design (Van Aken, 2007). In order to allow for customization and ownership, we stressed the importance of key goals of NKEplus (patient safety, quality patient engagement time). The team outlined certain minimum specifications that would create just enough structure to create the desired patient-to-nurse and nurse-to-nurse interactions. But important details regarding roles and specifics around safety were left up to the unit to decide. For example:

How would roles be coordinated before end of shift? How would roles be coordinated during the shift change?

What safety check will be performed during the exchange while two nurses are in the room with the patient?

With this approach, we needed to make the questions very specific, to keep the staff members focused on where help was needed. This allowed for focused contributions by everyone, and kept them on-goal, while giving them the flexibility to own the design.

Made for Trialing

Fail early to succeed sooner is one key hallmark of design thinking (Kelley & Littman, 2005). Embracing this design principle and the idea of trialing small tests of change through PDSA cycles in real work settings (Schilling, 2009), our team wanted to find an efficient way to have people experience the many ideas that comprised the suite of solutions that made up NKEplus. That way, they could modify these ideas as needed and personally experience the benefits associated with the concept before agreeing to go-live with them.

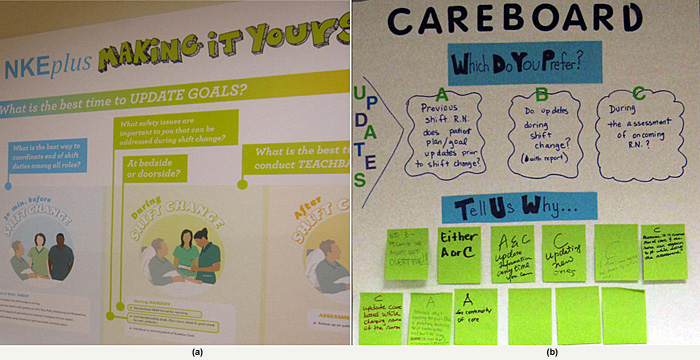

To facilitate this, we broke down the system of concepts into bite-size tests, which made it easy to pilot these ideas and encourage experimentation (much like applying the rapid prototyping principle, but in this case, in the implementation rather than in the field testing phases of design). Systematically, the frontline staff members tried out one bite-sized concept at a time, working out the details of how they preferred it to be executed in their unit’s context (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Posters used to illustrate: (a) the areas of customization; (b) ideas for different options.

In addition, we demarcated a public space, the Hallway of Dialogue, for staff to post their communication posters and solicit feedback from each other (Figure 10). The goal here was to leverage the creativity of staff champions to keep the issues, feedback and ideas visibly in front of the entire unit. This was especially valuable in reminding people why we were doing what we were doing.

Figure 10. Encouraging trialing and creativity: Hallway of Dialogue.

Try, Then Assess

One particular hallmark of NKEplus that encountered tremendous resistance from the nurses in our implementation was the idea of exchanging the entire report at the bedside with patients. When presented with the concept, nurses were adamant that: (1) they didn’t have the time to do that, (2) it was unnecessary, (3) the added value was not worth the extra time, or (4) it was difficult and uncomfortable. However, we knew from earlier field tests that many of the nurses who had tried this new process felt that there was an adjustment period in getting used to it, but that it was no more time consuming than their existing way of exchanging information at the nursing station. More importantly, there was added value in exchanging information at the bedside that the nurses never expected. The nurses were surprised to learn that they could plan for their day better after seeing their patients early on and that they could visibly talk through the report by showing each other intravenous lines and wounds.

With all of the resistance we had encountered in our previous implementation efforts, we realized we needed to create an environment where people felt like they had nothing to lose by trying something new. We wanted them to experience the concept, then make a decision, rather than to judge the idea based on what they were told. But to be genuine, we also knew we had to be fully prepared to concede to the staff’s judgment, if the concept did not bear proof of benefit.

So rather than just telling them, and trying to convince them of the benefits that others had experienced, and that patients loved the warm handoff, we said, “Don’t take our word for it.” We asked the nurses if they would be willing to try it for a week. And if the effort was not worth the benefit, they could continue with their existing practice, which was to do part of the nurse shift exchange outside the room, and part of it inside.

When we reconnected with the unit for feedback one week later, the nurses decided their standard would be to conduct the entire exchange at the bedside, rather than partly inside, partly outside because they had experienced benefits by doing this which they hadn’t believed in, and hadn’t been able to imagine.

Crowdsourcing to Address Challenges and Pushback Directly

In the process of extensive mini-trials, many challenges and pushbacks surfaced. For example, around bedside reporting, questions were raised such as: What happens if the doctor is in the room? What if family members are present? How do we manage needy patients with a lot of questions or demands when we have to see five patients in a period of 30 minutes without short-changing other patients or slowing down the process?

This time around, our team was committed to take a more facilitative approach to problem solving these issues as a part of the implementation. In early efforts, we had anticipated the questions that we would receive and had prepared answers and the design team did the responding. We soon learned that the best approach was to actually throw the question back at the unit as a whole, and solicit answers from their peers. So, rather than attempting to provide all the answers – which we sometimes possessed and sometimes didn’t – we relied on the wisdom of the unit staff, to problem solve and facilitate situations where nurses could show each other what to do in specific situations. In some cases, this took the form of nurses role-playing scenarios to get a feel for the right approach in specific situations. These teachable moments were captured on video and later used for training purposes.

In other cases, where specific barriers existed that might inhibit the success of the entire system, we pulled together a multi-disciplinary team of staff to call out and address problems through a rapid idea generation workshop.

Not surprisingly, both approaches resulted in much better and more credible answers and ideas that strengthened staff ownership and engagement. Rather than having designers or project managers attempting to answer questions related to clinical practice, the clinicians provided the expertise.

Designing for Action

In our earlier implementations of NKEplus, most of the work started at a point where we were telling people what they needed to do. We tried to generate excitement by being “cheerleaders” – expressing encouragement that was often heartfelt on the giving end, but not on the receiving end. Having built a solid foundation of understanding, ownership and proof of concept over the period of the three-week “soft start” process, we found that the unit was chomping at the bit to start testing out the ideas and was ready to go live and actually implement what felt like their own solutions.

Designing for Clear Communication

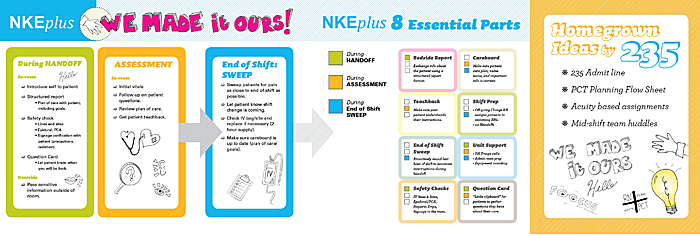

At this stage of the process, design and design thinking played a vital role in bringing clarity to a complex system of concepts. The key to NKEplus and the redesign lay in the preparation and coordinated mechanisms that supported the shift reporting and warm patient engagement at the bedside. Here, visual and information design played a key role in clarifying what was decided, and what the unit had agreed on as “their” NKEplus. To do this, we created posters that clearly laid out all the “essential parts” and posted them all around the unit (Figure 11). This clearly spelled out what all the key pieces were, so that they could be kept visible in front of people at all times. That way, no one forgot important “back-end” support pieces that needed to happen in order to support the nurses’ shift report without interruptions.

Figure 11. “We made it ours” poster.

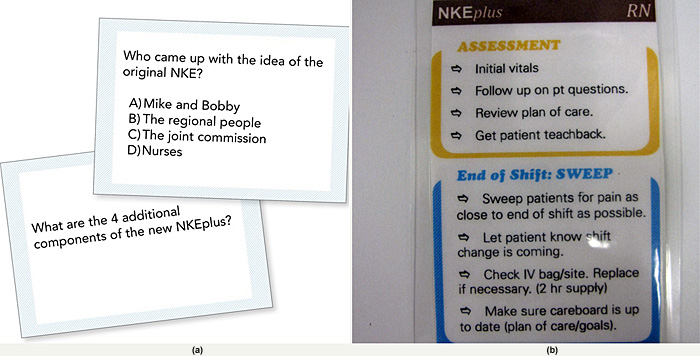

In order to actively encourage the staff to “review” and remember everything, we also created quiz game cards that could be used at staff meetings and huddles (Figure 12a). Many of these quiz questions included funny “throw-away” answers that kept it light and engaging.

For each staff role, e.g., nurses, nurse assistants, unit assistants, we spelled out the protocol describing what should take place just before the shift, and during the shift change, on portable badge cards. These badge cards were given to people so that they could carry them and refer to them as needed (Figure 12b).

Figure 12. Creative ways to keep the ideas in front of staff:

(a) Huddle quiz cards; (b) Role-specific badge cards.

Building anticipation for the Change

We were very intentional about making the official “go-live” memorable to the entire unit. Our strategy was to build a sense of anticipation on the days leading up to the change, to get as many people involved as possible, and finally, to make the first day of change stand out.

On the days leading up to the go-live, there was a daily countdown to build a sense of anticipation. The unit convened huddles on a daily basis the week leading up to the go-live, and we started reminding everyone how many days were left before kickoff.

Design for Acknowledgement and Accomplishment

As we went live, we took every opportunity, big and small, to celebrate all of the hard work of each staff member in incorporating new processes and behaviors into their practice. We found that celebrating accomplishments was critical to helping the staff maintain new behaviors.

Making the Change Moment Memorable

The Go-Live day was a celebration in itself. Members of the frontline staff came in on their day off to help decorate the unit and pass out our NKEplus badge cards. Managers, our design team, and hospital leadership came to all three shifts to serve made-to-order smoothies and ice cream sundaes. Moreover, to get others involved to help celebrate and “commemorate” the occasion, we invited physicians, frontline staff from sister units, and hospital leaders to visit and provide support.

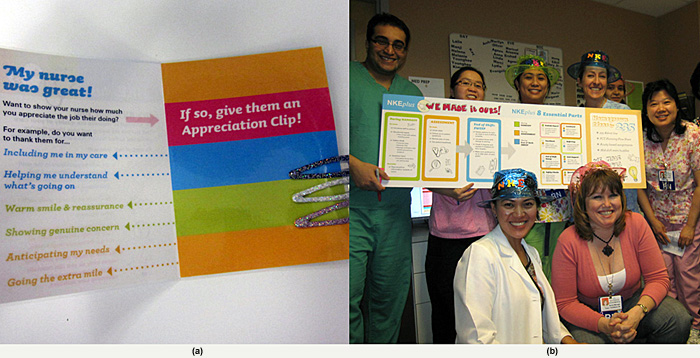

During the course of the NKEplus go-live, we also found that a great way to reinforce the change was by getting patients involved. Managers actively solicited patient feedback about bedside reporting to hear how it was going. They also created a Patient Engagement Competition, facilitated by tabletop cards (Figure 13a) where patients could award outstanding nurses for involving patients in their bedside reporting. At the end of each week, winners of the competition were awarded Starbucks gift cards.

Figure 13. Making the Go-Live memorable:

(a) Patient engagement card; (b) Go-Live celebration with staff.

Making Progress Visible and Engaging

After the go-live, we focused on sustaining NKEplus by keeping staff engaged and mindful of the change that was happening.

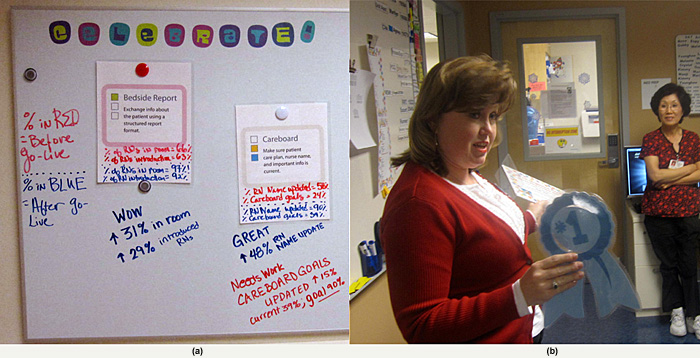

From a traditional healthcare implementation perspective, one of the most important aspects of sustainability is showing progress in terms of data. This allows for a culture of learning and growing where staff can make regular adjustments as needed (Van Aken, 2007) rather than “refreezing” a single new process. In this regard, working with the unit manager, we focused our efforts in finding a place where people could consistently expect to see data, so that we could keep it visible and in front of people. We established a “celebration” board in the hallway just outside the managers office where we shared unit progress in engaging, creative ways in which the staff used colorful, simple elements rather than the traditional method of “posting” reports.

We also worked with the unit manager to celebrate staff accomplishments related to NKEplus, big and small. During huddles, managers celebrated individual staff accomplishments by handing out ribbons and certificates to those who had made significant contributions. At the same time, large colorful posters describing the unit’s ‘customized by them’ NKEplus, as well as regular visits from hospital leaders, provided an ongoing sense of pride and celebration about this change for the unit as a whole.

Figure 14. Engaging ways to show accomplishments:

(a) One approach used for NKEplus to show progress; (b) Huddles highlight progress and accomplishment.

Refreshers and Reminders of the Cause

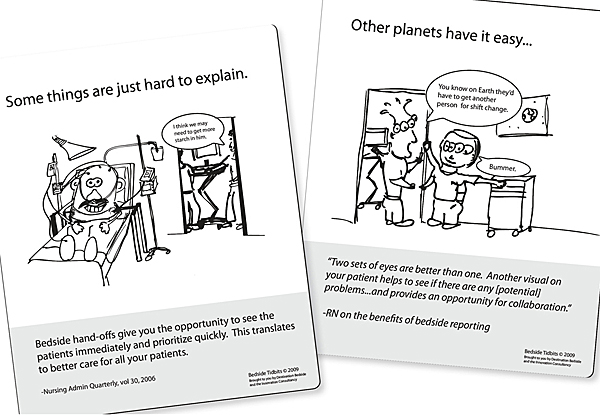

We also developed assets that managers could use to refresh the message, and remind people why they were doing what they were doing through what were called “Bedside Tidbit Cards” (Figure 15). These were “Farside-esque” cartoons that used humor as a vehicle to communicate messages that had already been conveyed, but in a fresh and unexpected way. The Bedside Tid-Bit Cards were left around the unit at nurses’ stations for people to discover and displayed as computer workstation screensavers.

Figure 15. Bedside Tid-Bit cards.

Results and Conclusions

In the introduction, we posed the question: Can design thinking be constructively coupled with thinking about change management in order to help practitioners not only design better service innovations, but also improve the implementation of service innovations?

Our experience suggests that it can indeed. The case of NKE implementation provides a practical, albeit small-scale, confirmation of the cross-discipline concepts put forth by Van Aken (2007) and Junginger and Sangiorgi (2009).

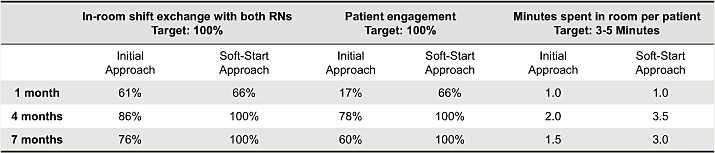

We have described the qualitative differences in tone of staff feedback throughout this paper, and summarized these in Tables 1 and 3 previously. Clearly, the staff felt better with the ‘soft-start’ approach. But did that difference make a difference in performance?

Comparing the quantitative process metrics from the initial implementation versus the more human-centered, ‘soft-start’ approach in Table 4 suggests that there was indeed a difference in performance, and that the difference is manifested in both the ultimate level achieved and the sustainability of the change over time.

Table 4. Process metrics: initial approach vs.‘soft-start’ approach.

The two approaches achieved somewhat similar results in the short term on the three indicators we tracked. Recalling the comments heard “behind-the-scenes” in the initial implementation – “we’re doing it because we have to” – seems to suggest that compliance approaches can work.

However, note the differences observed at the end of the seven-month data collection period. Compliance with the key service design ideas of both nurses going into the room and actively engaging the patient in conversation during the shift-change handover was 100% on both indicators with the human-centered ‘soft-start’ implementation approach, versus 76% and 60%, respectively, with the initial approach. Furthermore, nurses who were involved in the ‘soft-start’ approach were spending twice as much time on average as their counterparts who went through the initial approach (3 minutes versus 1.5 minutes).

This finding is consistent with broader findings from the field of social movement theory when comparing what are called “compliance approaches” to “commitment approaches” (see, for example, Bibby, Carter, Bate, & Robert, 2009). Being actively involved in understanding both the why and the what of the service innovation (commitment) is essential to sustainability over the longer term.

Clearly, ours is a very preliminary finding based on a single case. We have not studied this rigorously. But given that the case of NKEplus implementation provides a practical, suggestive confirmation of concepts put forth by theorists such as Van Aken (2007) and Junginger and Sangiorgi (2009), and that the results are consistent with those found in other fields that study compliance versus commitment, we believe that more study of approaches that involve designers in the ways we have described here is in order.

An important drawback in our more human-centered approach that must be acknowledged revolves around the amount of time and effort required during the extensive, three-week, ‘soft-start’ process. While we did not record the amount of time spent by design team members and front-line professional staff in this period of up-front engagement, it was substantially more than the effort required in the initial approach. During the qualitative feedback session, the RNs commented on how slow the process was and the unit manager shared similar sentiments, commenting that, “Don’t get me wrong. What we did was fantastic. But it took a lot out of us.”

Reflecting on this, we are continually modifying the ‘soft-start’ approach to maximize each individual facilitative effort required in subsequent implementation work that we do, and streamlining less “value-added” activity. Conceptually, we imagine that there is some optimal, minimum level of effort that still delivers sustainable results. However, in identifying this level it would be important to compare like-for-like efforts over some extended time period. It might be, for example, that when one looks over months of effort what we have done is not so much to increase the total amount of effort required for sustainable results, but simply front-loaded it into the three-week ‘soft-start’. If the service providers are truly committed to the change, much less supervisory effort may be needed later to sustain it. A further complication is the fact that one must also quantify the economic benefit of achieving a given level of sustainable performance. For example, in our case, there was a 100% versus 76% compliance rate on the indicator of both nurses going into the patient’s room. The economic value of that 24% higher compliance rate must be compared with the higher cost of the ‘soft-start’ approach in order to determine if this new approach was a good investment of organizational resources.

Finally, it is also important to once again note that our service providers were relatively highly paid professionals accustomed to autonomy and control over their daily work. A similar situation might also exist in service design in legal or financial firms, or in educational institutions, but we recognize that it might not necessarily apply in all service industries. We cannot say how much of a factor this was.

In summary, while we believe our case study is suggestive of a positive path for future development in the design sciences, we have raised more questions than we have answered. We would like to encourage our academic colleagues to design further research along a number of interesting avenues of investigation:

- This case study suggests that combining design and change management thinking in the service innovation design implementation process produces better results. Is this result replicable in larger, better designed studies?

- What other combinations of design and change management concepts might also be useful? How might practitioners select combinations to suit their situations?

- What are the optimal components and resource requirements to support the business case for an implementation process like the one described here, given an organization’s required return on investment?

- How much do the service providers’ values and traditions of professionalism, autonomy and control matter in terms of selecting an optimal human-centered implementation design?

- Could designers be helpful to organizational change managers even if they were not involved in designing the actual service change; i.e., is this potentially a new application for designers?

References

- Bate, P., & Robert, G. B. (2007). Bringing user experience to healthcare improvement: The concepts, methods and practices of experience-based design. Abingdon, UK: Radcliffe.

- Bibby, J., Bevan, H., Carter, C., Bate, P., & Robert, G. (2009). The power of one, the power of many: Bringing social movement thinking to health and healthcare improvement. Warwick, UK: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement.

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 56-71.

- Bodenheimer, T. (2007). The science of spread: How innovations in care become the norm. Oakland, CA: California Healthcare Foundation.

- Erickson, T. (1995). Notes on design practice: Stories and prototypes as catalysts for communication. In J. M. Carroll (Ed.), Scenario-based design: Envisioning work and technology in system development (pp. 37-58). New York: Wiley.

- Ford, J. D. (1999). Organizational change as shifting conversations. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(6), 480-500.

- Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., & Kyriakidou, O. (2004). Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly, 82(4), 581-629.

- Holmlid, S., & Evenson, S. (2006, October). Bringing design to services. Paper presented at IBM Service Sciences, Management and Engineering Summit, New York.

- Hord, S. M., Rutherford, W. L., Luling-Austin, L., & Hall, G. E. (1987). Taking charge of change. Alexandria, VA.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- IDEO (2008). IDEO human centered design toolkit field guide (2nd ed.). Retrieved Oct 15, 2009. from: http://www.ideo.com/images/uploads/work/case-studies/pdfs/IDEO_HCD_FieldGuide_for_download.pdf.

- Junginger, S., & Sangiorgi, D. (2009). Service design and organizational change: Bridging the gap between rigour and relevance. Paper presented at 3rd IASDR Conference on Design Research, Seoul, Korea.

- Kelley, T., & Littman, J. (2005). The ten faces of innovation: IDEO’s strategies for beating the devil’s advocate and driving creativity throughout your organization. New York: Doubleday.

- Langley, G. J., Moen, R., Nolan, K. M., Nolan, T. W., Norman, C. L., & Provost, L. P. (1996). The improvement guide: A practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. New York: Harper.

- Morelli, N. (2002). Designing product/service systems: A methodological exploration.Design Issues, 18(3), 3-17.

- Schilling, L. (2009). Implementing and sustaining improvement in health care. Oak Brook, IL: Joint

Commission Resources. - Shewhart, W. A. (1931). Economic control of quality of manufactured product. New York: D. Van Nostrand.

- Shostack, G. L. (1984). Designing services that deliver. Harvard Business Review, 62(1), 133-139.

- Van Aken, J. E. (2007). Design science and organization development interventions: Aligning business and humanistic values. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 43(1), 67-88.