Growing Tessellations: Negotiation and Wayfinding in Interdisciplinary Design Practice

Laureen Mahler 1,* and Bahareh Barati 2

1 Aalto University, Espoo, Finland

2 Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, the Netherlands

As design practices are increasingly positioned in interdisciplinary contexts, origami tessellations present a powerful analogy for navigating shared design processes. This paper explores “growing tessellations”, an innovative approach that integrates craft, biofabrication, and digital fabrication to create dynamic tessellated structures. By examining the relations among diverse processes and making traditions involved in growing tessellations and drawing on Ingold’s theory of entanglement, we illustrate the intricacies of a living design process based on practice-led research methodologies. Our analysis of design events reveals the negotiations and novel affordances of individual processes, and these entanglements are captured through intermediary and final artifacts that are crucial in materializing and nudging diverse becomings. This reconstruction of the design process is aided by the development of a reflective and generative visualization tool, through which we untangle the symbiosis between designing-with and practice-led research, with implications for biodesign, digital fabrication, and beyond.

Keywords – Biofabrication, Designing-with, Negotiation, Practice-led research, Tessellations.

Relevance to Design Practice – We provide a methodological framework and visualization tool for navigating diverse entanglements in interdisciplinary design research. Through wayfinding techniques that facilitate noticing and negotiating, specific design events and their corresponding affordances can be identified, engaged with, and synthesized.

Citation: Mahler, L., & Barati, B. (2025). Growing tessellations: Negotiating and wayfinding in interdisciplinary design practice. International Journal of Design, 19(3), 31-61 https://doi.org/10.57698/v19i3.02

Received February 11, 2025; Accepted October 27, 2025; Published December 31, 2025.

Copyright: © 2025 Mahler & Barati. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-access and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: laureen.mahler@aalto.fi

Laureen Mahler is a doctoral researcher at Aalto University in Finland. Her research focuses on the designer-maker and the cultivation of knowledge through making, as well as the role of material engagement in fostering a more holistic conception of design. Fundamental to her work is the visuality of making: specifically, how spatial engagement facilitated by craft-driven practices supports interdisciplinary research and provides new perspectives on designing. She works in the field, laboratory, and workshop, combining material-driven exploration, craft methodologies, and digital tools. Prior to joining Aalto, she was a university lecturer at design faculties in Germany and the United States.

Bahareh Barati is an assistant professor in the Making-with research cluster and co-founder of the Material Aesthetics Lab in the Department of Industrial Design at Eindhoven University of Technology. Her research explores the intersections of Material-Driven Design, Biodesign, and More-than-Human design, aiming to materialize alternative and reparative ways of relating and cohabiting in More-than-Human worlds. Her work emphasizes intimate, in-situ modes of engagement and leverages digital fabrication and computational tools to support transitions toward regenerative ways of making and living. Bahareh publishes in leading venues across design, engineering, and Human-Computer Interaction.

Introduction

Designers are makers, and in that making lies vital potential for knowledge production: this is the notion at the heart of practice-led research, which, through systematic documentation and analysis of practice, argues that making is knowing (Dunin-Woyseth & Michl, 2001; Frayling, 2012). This growing field of research has, in recent years, proposed new ways of approaching materials and their agencies (e.g., Tuin & Dolphijn, 2012), demonstrated the importance of process-focused inquiry (e.g., Ingold, 2013), and provided a venue for innovative modes of collaboration (e.g., Groth et al., 2022). At the same time, designers across the discipline are pursuing sustainable approaches by engaging with a broader repertoire of materials, including living organisms (Karana et al., 2020). These pursuits are further facilitated by new technologies and digital fabrication techniques, requiring designers to navigate through and negotiate their intentions with disparate agencies. Accordingly, there is a need for increased mindfulness about interaction and negotiation in the design process, as well as a renewed urgency to design with intentionality, thus making space for diverse agencies. This is reflected in the evolution of designing-with and more-than-human design (Wakkary, 2021), as well as in the growing emphasis on processes rather than outcomes across the scope of design research (e.g., Gaver et al., 2022). This paper proposes that through practice-led research, a better understanding of the conditions and consequences of designing-with can be achieved; furthermore, it cultivates insights about the value of entangling practices, techniques, and expertise in interdisciplinary contexts.

The Growing Tessellations project presented here brought together two design researchers and makers with diverse expertise: one with a practice-led focus on bio-based materials and craft methods in origami tessellations, and the other with an extensive background in smart and biological materials from a Material-Driven Design (MDD) perspective. This resulted in an exploratory collaboration that combined tessellations and biofabrication in order to investigate whether dynamic, three-dimensional structures could be grown rather than folded. Our objective in this project was to push our own understandings of practice by integrating non-human makers—in our case, growing materials and digital fabrication—into a living design process built on the notions of reflection and negotiation. In achieving that, we set out to discover how designing happens differently with living materials, and, additionally, in what ways the agents and processes involved might converge to embody a living design process (Alexander, 2002b). Our respective backgrounds intertwined craft techniques centered around paper and folding together with digital tools and laboratory-based mycelium work, and we immediately found that craftsmanship (both manual and digital) and mycelium shared numerous commonalities, creating a foundation for fruitful exchanges between materials and processes.

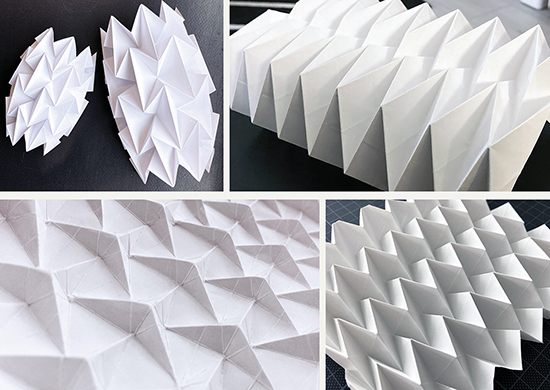

With practice-led research as a methodological basis, we aimed to deconstruct and analyze our process in order to address crucial gaps in the largely philosophical approach of designing-with: specifically, how novel affordances are unveiled, where relevant critical theories lie, and how artifacts serve as crucial access points for the analysis of emerging practices. The seemingly disparate methods of creating origami tessellations and growing organic material provided a serendipitous departure point for the project. While necessitating close collaboration and the development of innovative tools and techniques, it also served as a conceptual model to navigate the theoretical aspects of the research. Tessellations are defined as periodically repeating patterns that extend indefinitely with no gaps, and origami tessellations merge mathematics and craft to produce dynamic, three-dimensional structures that utilize tessellated patterns (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Origami tessellations:

dynamic structures that use the (clockwise from top left) waterbomb, Kresling, Miura, and Resch triangle folds.

As such, origami tessellations embody a simultaneity requisite for designers working in interdisciplinary contexts: a necessary adherence to formal and structural constraints alongside an openness to agency, emergence, and negotiation. In particular, tessellations underscore the dynamic and emergent nature of holistic designing, where distinct disciplinary processes and traditions interweave to create innovative and sustainable outcomes. In the case of the tessellation, mathematical parameters dictate grids and unit cells, but emergence engenders the dynamic, three-dimensional form through a process called “collapse” (Figure 2). In the processes depicted here, yet more diverse and distant agential capacities—spanning fungi, fibers, humans, tools, and 3D printers, to name just a few—are incorporated, allowing diverse practices and making traditions to entangle, negotiate, and become together (cf. Camere & Karana, 2018). Tessellations as a concrete medium, defined by specific mathematical and material properties, thus serve as a useful boundary condition to navigate the entanglements and negotiations of such multivalent processes.

Figure 2. Folding an origami tessellation (from left to right):

creating a grid, pre-creasing the unit cells, and collapsing the form into a dynamic structure.

This paper therefore joins a developing body of research that focuses on process rather than outcomes of designing and making (e.g., Meiklejohn et al., 2024; Oogjes & Wakkary, 2022), including examination of the unexpected turns that make clear-cut narratives messier and more controversial (e.g., Ikeya et al., 2023). In our work, we draw on Ingold’s entanglement theory of lines and knots (Ingold, 2013; 2015) and Alexander’s (2002a; 2002b) living design process to identify the entanglements and negotiations between human and more-than-human actors, and investigate how these are mediated through tools, techniques, and artifacts. We then unpack our practices of making mycelium-based tessellations and reconstruct the design events (Roberts, 2014; Whitehead, 1979/1929; Whitehead, 2022/1919; Wilkie, 2018) deemed as vital moments of translation between diverse courses of action and the creation of keystone intermediary artifacts. Our work contributes to ongoing discourses in both the evolving field of designing-with as well as practice-led research, with particular emphasis on the importance of reimagining practice in material-driven, more-than-human, and interdisciplinary contexts. The contributions are therefore threefold: 1) detailed accounts of our living design process aimed at growing tessellated structures with mycelium, 2) the investigation of intermediary and final artifacts as both generated from and prompting acts of negotiation, and 3) a methodological tool for mapping and synthesizing the interactions among different craft, digital, and biofabrication processes (growing tessellations).

Related Work

This paper outlines a collaborative approach to growing “origami” tessellations that incorporates craft as well as bio- and digital fabrication, thus connecting several established and emergent fields in the broad discipline of design. Combining this diverse body of work with methodologies from practice-led research, we aim to address the existing gap between philosophical approaches to, and concrete processes and implications of, designing-with.

Perspectives on Making, Practice-Led Research, and Designing-with

Practice-led research is a growing field in which design research and craft practices are closely integrated (Nimkulrat, 2012). Whether papermaking, weaving, ceramics, glass-blowing, or anything in between, this branch of design research investigates hands-on practice as vital in the production of knowledge (Candy & Edmonds, 2018) and is predicated on the notion that making and knowing are inseparable (e.g., Mäkelä, 2007; Pye, 1995/1968; Sennett, 2008; Vega, 2021). Craft’s prominent role in practice-led methodologies indicates a fundamental aspect of this type of research: inherently process-driven, it aims to investigate tacit knowledge—or knowledge implicit in experience—which is particularly difficult to explicate (Frayling, 2012; Polanyi, 1997). These experiential aspects of designing are equally instrumental in new-materialist and post-humanist views and concepts, and the work of Barad, Haraway, and Ingold has been of particular influence in shaping the related discourse around design practice (e.g., Nordmoen & McPherson, 2022; Shlain & Goldberg, 2019; Ståhl et al., 2022). More-than-human design, for instance, emphasizes the importance of diverse agencies in the design process, from technologies to living entities (e.g., Verbeek, 2008; Wakkary, 2021). This includes making space for a plurality of actors and perspectives (e.g., Akama et al., 2020; Mancini et al., 2012), considering ethics and care in work with living materials (e.g., Chen & Pschetz, 2024; Oktay et al., 2023), and including first-person relational perspectives in research methodologies (e.g., Goveia da Rocha et al., 2021; Ofer & Alistar, 2023; Oogjes & Wakkary, 2022). Closely aligned with more-than-human design is the concept of designing-with, which aims to upend human-centered approaches with a focus on diverse perspectives and interactions between materials, machines, and species (e.g., Ávila, 2022; Ooms et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2017).

These distinct areas of design research share a common objective of fundamentally rethinking the role of process, and their methodologies are thus not only complementary but capable of facilitating insightful cross-pollination. In practice-led research, comprehensive documentation serves as a mode of accessing and analyzing the actions that take place during the making process (e.g., Lehmann, 2012; Mäkelä & Nimkulrat, 2018). Documentation also allows for reflection—a critical aspect of both practice-led research and more-than-human approaches (e.g., Dalsgaard & Halskov, 2012; Meiklejohn et al., 2024; Pedgley, 2007). In reconnecting design researchers with making processes, these parallel areas of research also generate essential discourses about the agency of materials (e.g., Tuin & Dolphijn, 2012), the significance of making in the generation of knowledge (e.g., Dunin-Woyseth & Michl, 2001), and the importance of morphogenetic approaches in designing (e.g., Ingold, 2013).

Tessellations in Design, Engineering, and HCI

Origami tessellations encompass a wide range of design-related research, and recent applications include innovations in auxetic textiles (e.g., Mohan, 2020; Wang et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022) as well as packaging design (e.g., Kouko et al., 2023). Both instances illustrate the significance of tessellations’ mathematical and mechanical properties in functional applications, and this is indicative of a long history of interdisciplinarity amongst mathematics, engineering, and design in the context of tessellations (e.g., Davis et al., 2013; Kankkunen et al., 2022; Meloni et al., 2021; Zhang & Zhao, 2024). Similarly, applications of origami tessellations are well represented in HCI-related research, including foldable interactive displays (Kinoshita et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2021; Olberding et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2015), deployable technologies (Liang et al., 2023; Zirbel et al., 2013), soft robotics (Kaufmann et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022), actuators (Purnendu et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2024), metamaterials (Chen et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2018), and shape-changing tessellations developed with 4D printing (e.g., Feng et al., 2024; Mühlich et al., 2020; Narumi et al., 2023).

At the same time, the shape-changing capabilities of tessellations have been examined in both architecture and soft robotics, including their ability to flat-fold, capture multiple degrees of freedom, and demonstrate a negative Poisson’s ratio (Felton et al., 2014; Narumi et al., 2023; Yousefi & Parlac, 2023). In addition to mechanical properties, the experiential possibilities of tessellations are especially evident in designing tangible interactive interfaces that use origami-inspired structures (Kinoshita et al., 2014; Olberding et al., 2015). These include wearable technologies that adapt to user preferences (e.g., Ku et al., 2024), as well as physical supplements to digital technology that utilize corrugated structures to enhance user interaction (e.g., Tan et al., 2015). The tunability and flexibility of tessellations are of particular interest here, where research focuses on customizing user experience and making digital information available in tangible forms (e.g., Chang et al., 2020).

Biofabrication and the Practice of Growing

With the shift towards more sustainable practices, biodesign and biofabrication have become growing areas of focus, including design that incorporates microorganisms—such as microalgae, bacteria, and fungi—into the fabric of (often interactive) artifacts (e.g., Groutars et al., 2022; Ikeya & Barati, 2023). A developing body of work investigates the offerings of such a partnership with biological nonhumans for interface design (e.g., Barati et al., 2018; Breed et al., 2024), sensing and actuating (e.g., Yao et al., 2015), and growing parts (e.g., Bell et al., 2023). Biofabrication with mycelium makes up a significant portion of this research and includes the cultivation of fungal networks to achieve desired forms and/or functionalities (e.g., Genç et al., 2022). Recent work in mycelium-based biofabrication demonstrates a wide range of applications, from mycelial textiles and wearables (Lazaro Vasquez et al., 2024; Vasquez & Vega, 2019), to self-healing (Elsacker et al., 2023) and repair (Ng et al., 2021), to comprehensive tools for prototyping with mycelium (Bhardwaj et al., 2021; Gough et al., 2023). Such works in Growing Design (Camere & Karana, 2018; Karana et al., 2020) address an urgent need to reconsider how we use natural resources (D’Olivo & Karana, 2021), what opportunities biofabrication offers (Gough et al., 2021), and the ways in which growing processes can be used to foster innovation (Chen & Pschetz, 2024; Zhou et al., 2022). In addition, recent work examines both the sustainability and growing-as-making potential of regenerative design, in which living materials are introduced as active agents into the design process (Pollini & Rognoli, 2024).

Growing Tessellations

The shift to process-focused perspectives has led to greater consideration of how knowledge is developed through the design process, with the examination of processual events and intermediary artifacts as central elements of designing in a research framework (Nimkulrat, 2012; Perner-Wilson et al., 2010; Wiberg et al., 2013). Recognizing design events as units of analysis (Oogjes & Desjardins, 2024; Whitehead, 2022/1919) has offered fresh insights into how making contributes to innovative design processes, whether by illuminating agencies and roles of materials, clarifying designers’ intentionalities, or focusing inquiry on different modes of becoming (Roberts, 2014; Wilkie, 2018). In our approach to growing tessellations, we focused on events that defined the design process, with the objective of tracing how those events informed subsequent actions. This emphasis allowed the design process itself—and the negotiations inherent in it—to shape the project as it unfolded. Our concept of growing tessellations can thus be leveraged in following the lines and knots of designing and making processes, with intermediate and final artifacts serving as access points for analyzing those processes.

To support our understanding of “growing tessellations” as a concept and unpack its corresponding events and processes, we look to the theory of entanglement and its notion of lines and knots that form a process of becoming (Ingold, 2013, 2015, 2021). In Ingold’s view, the process of becoming is exemplified in the life of a line (Ingold, 2015). A line travels along its own path, from which it entangles with other lines, creating a knot. Thus, in both social and creative endeavors, interactions can be viewed as a meshwork of entangled lines, each retaining its particularities but also intertwining to create new “knots.” Specific to designing, these lines represent actors or processes—constituents in the making process—and their meshwork becomes a configuration of correspondence (Ingold, 2013).

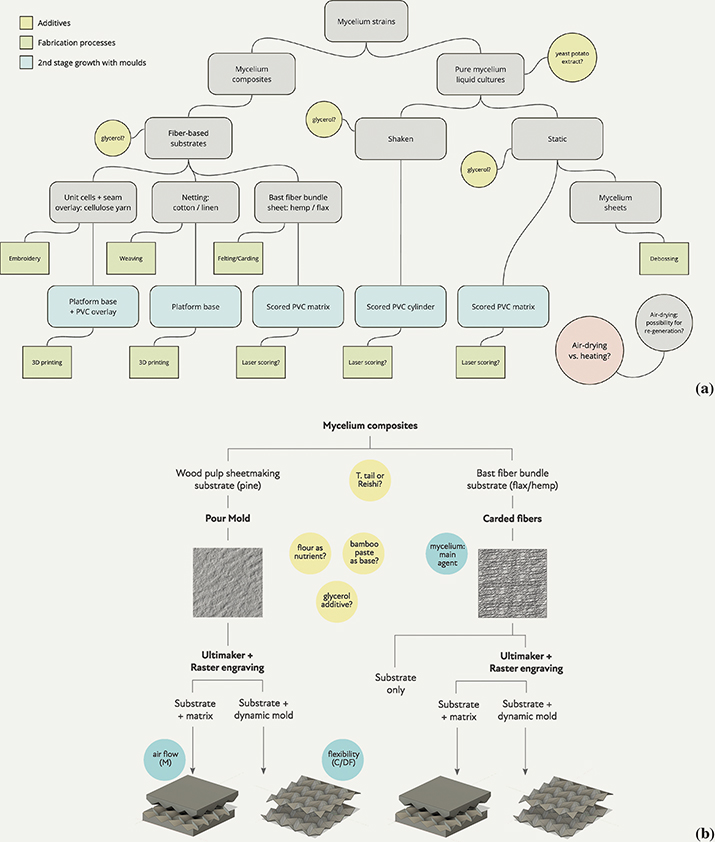

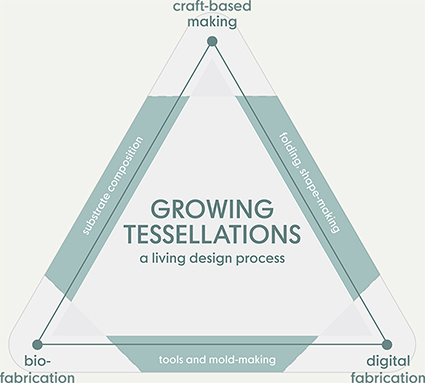

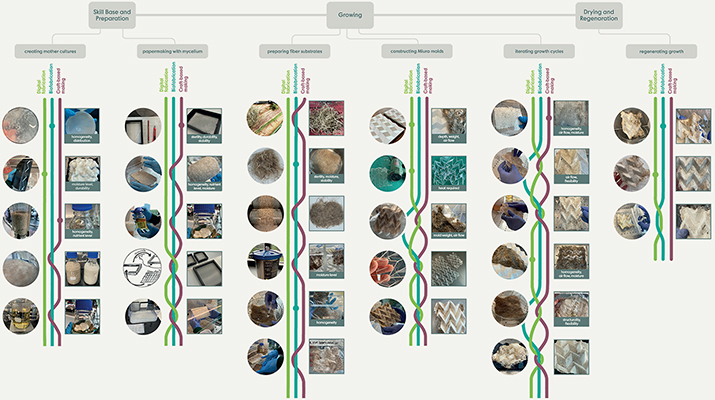

This meshwork and the flux in which it operates are part of a living design process, as described by Alexander (2002b): “the nature of order is interwoven in its fundamental character with the nature of the processes which create the order” (p. 2). In the work presented here, diverse techniques, tools, and perspectives converge to collectively shape events and their subsequent artifacts. By combining conventional making practices with interdisciplinary approaches focused on growing as a mode of designing-with, we engage with the contingency of growing tessellations: a living design process that entangles the diverse processes of craft-based making, digital fabrication, and biofabrication, as well as their corresponding techniques and tools (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Practices entangling:

amidst craft, digital- and biofabrication, “growing tessellations” provides concrete objectives and methodological framework.

Lines to Knots

As a basis for our synthesis of entanglements and growing tessellations, we consider craft-based making, digital fabrication, and biofabrication as distinct processes, or separate “lines.” Each exists with its own assemblage of techniques and tools, and thus distinct approaches and perspectives. Nonetheless, there are also commonalities that tie these practices together and thus lie at the core of the project structure.

Craft-Based Making

We define craft-based making as a material-driven endeavor that requires a practiced skillset and is necessarily characterized by motion, physical interaction with materials, and form-making (Adamson, 2007; Sennett, 2008). A crafted artifact “reveals both the material and the maker simultaneously” (Adamson, 2007, p. 95) and serves as the reification of a cycle of circular metamorphosis that involves construction, reflection, and subsequent opening up (Ingold, 2015; Sennett, 2008). Craft-based making also entails movement towards a form that is not predetermined and therefore unpredictable: a “workmanship of risk” (Pye, 1995/1968, p. 20). Regardless of the form it takes, craft represents an ongoing and ever-transitioning interaction between maker and material, one in which meaning emerges from material engagement. Therefore, in craft, “thinking and making are soluble with one another” (Dormer, 1994, p. 33).

Digital Fabrication

Though similar to craft in that it is dynamic and form-making, digital fabrication depends upon machinery “that is the intersection of the digital and non-digital” (Andersen, Wakkary, et al., 2019, p. 32). Software or code acts as an intermediary between maker and machine, whether the medium is 3D printing or CNC machining. While preconceptions of digital as mere automation are rapidly changing and making way for novel fabrication methods (Andersen, Wakkary, et al., 2019; Fossdal et al., 2023), the machine remains a vital and requisite element of the form-making process. Many cases in digital fabrication focus on executing a predetermined form with precision, although there are exceptions that tap into the vast potential for exploratory designing with machines (e.g., Goveia da Rocha et al., 2021; Zoran & Buechley, 2013). The latter approach shares many traits with craft and often combines the two both methodologically and ideologically (Andersen, Goveia da Rocha, et al., 2019; Barati et al., 2018; Devendorf et al., 2020). Notably, the notion of “digital craftsmanship” foregrounds the collaborative interplay between human makers and machines as a means of bridging craft and digital fabrication (Andersen, Wakkary, et al., 2019, p. 34).

Biofabrication

Biodesign broadly refers to the integration of living organisms into the design process to enhance the functional and/or aesthetic qualities of the final artifacts (Gough et al., 2021; Myers & Antonelli, 2018). Related to biodesign, biofabrication includes practices of “fabricating with biology” (Lee et al., 2020, p. 14). What distinguishes biofabrication from craft or digital fabrication is its reliance on living organisms, which have specific growth requirements and implications. This introduces unique stages into the biofabrication process, such as inoculation, growth, maturation, and harvesting. Typically conducted in dedicated laboratories or biolabs, biofabrication extends making activities beyond the traditional studio setting and requires strict protocols to ensure safety and prevent contamination by other microorganisms. Despite these specifications, biofabrication shares notable synergies with craft and digital fabrication: for instance, to produce sculpted or digitally-fabricated molds (e.g., Gough et al., 2023) and scaffolds (e.g., Zhou et al., 2021), and to post-process and shape biofabricated materials using craft techniques and digital technologies (e.g., Bell et al., 2023). The unpredictability of form and the importance of dialogue between the designer and the material are common traits in biofabrication, particularly when approached in an exploratory manner.

Entangling Processes

In our view, the overlaps amongst each of these processes are highly relevant to the notion of entanglement. On a practical level, craft, digital fabrication, and biofabrication all share a reliance on material engagement, the objective of form-making, and wayfinding through negotiation as a requisite condition for progression. More abstractly, they also represent methods that align closely with both practice-led research and more-than-human approaches to designing. They follow an unknown path rather than selecting a predetermined route, and their nature is thus more about attention than intention (Goveia da Rocha et al., 2022; Ingold, 2013, 2015; Tsing, 2015). If “lines” are processes, then “knots” are instances in which those processes intertwine, and this is fundamental to entanglement. Lines must ultimately tangle up with other lines, creating a meshwork of knots that illustrates entwining as a durable condition: a drawing together or correspondence that is always in process (Ingold, 2014; 2015). Through correspondence, process transforms into inquiry, and through making, inquiry translates to attention: an openness to happenings beyond the maker and a willingness to mediate between diverse actors. Knots in this sense can be seen as veritable footsteps along that path, flexible and in flux, but also retaining their particularities and recalling their linear origins.

Knots as Wayfinders for Becoming

We turn to Ingold’s entanglement and Alexander’s living design process in order to understand the process of growing tessellations as a negotiation among diverse actors, practices, and tools. Craft-based making, digital fabrication, and biofabrication are distinct “phenomena with their sets of apparatus” (Barad, 2007, p. 128), but the negotiations that occur in their entanglements present opportunities for emergence. Understood as domain shifts (Sennett, 2008), these are instances in which the application of specific expertise to diverse processes yields unexpected innovations (Rietveld & Kiverstein, 2014). In our view, domain shifts are moments of negotiative potential: knots defined by the intertwining of processes—the entanglement of lines—with the ability to transcend their individual capabilities and affordances. We define these particular knots as events because they are characterized by the convergence of processes, perspectives, tools, and techniques, and their entanglement is capable of facilitating change on both individual and collective levels (Whitehead, 1979/1929; Wilkie, 2018).

In events marked by entanglements, an artifact is a “local resonance in a reality composed of intersecting events” (Roberts, 2014, p. 977), encompassing not only a physical object but also the diverse constituents that intertwined to create it. In this way, artifacts are both mediated upon and mediators for ongoing events (Ståhl et al., 2022; Wilkie, 2018), regardless of their state of completeness. We therefore consider both intermediate and final artifacts as keystones for identifying design events, in that they reify the notion of diverse entities entangling to produce novel insights. To trace an artifact is to distinguish an event from an ongoing process (Wilkie, 2018) or to perceive knots from the meshwork of lines. In growing tessellations, our artifacts range from molds, customized tools, and documentation to in-progress samples and static prototypes, and their function is to provide access to the tangled essence of the events that produced them.

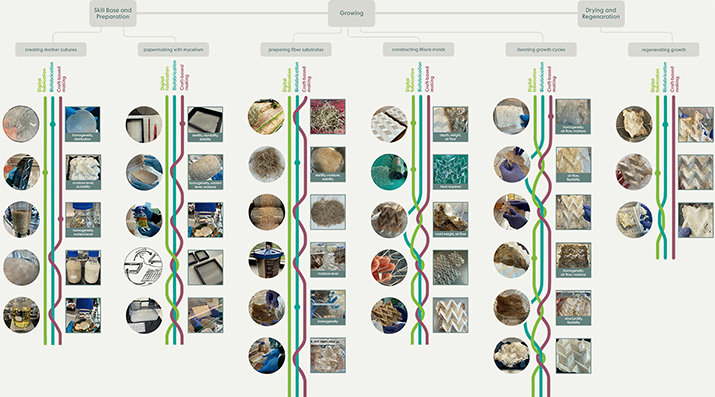

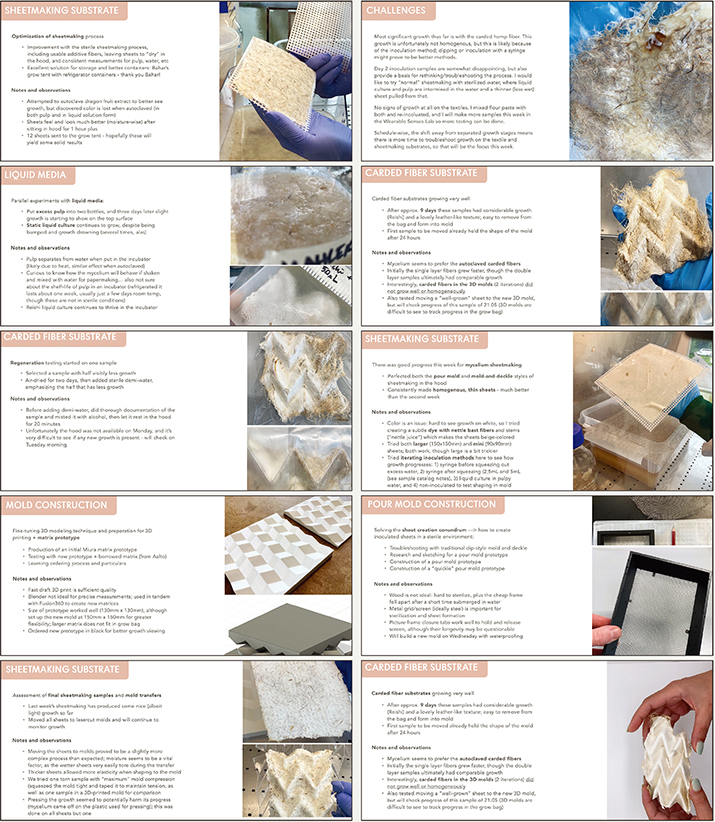

Methodology

This project was designed with a flexible structure that anticipated a workflow but remained adaptable, as determined by ongoing design events. Detailed documentation, as well as weekly team meetings, were thus essential to our methodology. This is reflected in a collectively developed project flowchart, which served as a living document that changed as the project progressed (Figure A1). Each weekly meeting provided a point at which to pause and “make space”: to consider the progress of the prior week, review artifacts, and discuss actions as determined by the negotiations we had observed. Therefore, analysis of design events and the documentation thereof became an active part of the process that prompted reflection and guided ongoing events (Bardzell et al., 2016; Dalsgaard & Halskov, 2012).

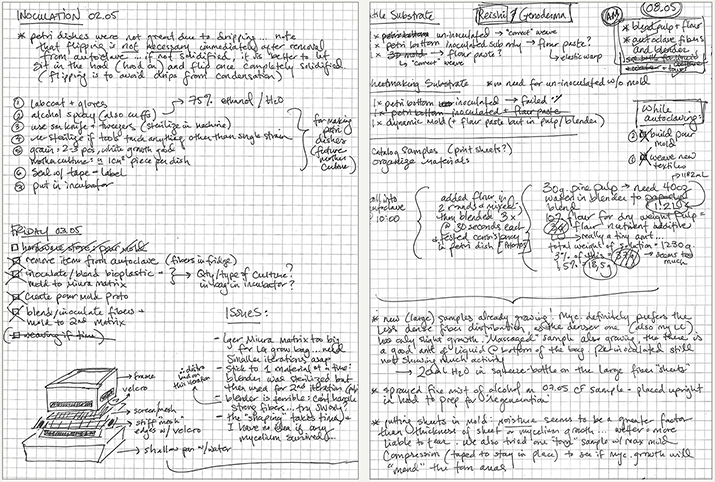

While we were working towards an ultimate objective (growing dynamic tessellations with mycelium composites), the nature of how we would achieve that aim remained in flux, and we could not foresee where impactful design events or moments of negotiation would occur. Accordingly, the structure and function of our documentation had to be holistic by design. We implemented methods that would capture diverse snapshots of both processes and artifacts: laboratory notes (Figure A10), a shared project diary (Figure A3), a comprehensive sample catalog (Figure A4), video footage (Table A1) and photographs (Figure A9) of laboratory procedures and samples, and a series of workflow instructions for project activities as they developed.

These varied forms of documentation then became intermediate artifacts in themselves and served as fundamental informants in the design process. From this extensive body of documentation, we employed two methods of analysis: 1) reconstruction of the design process through intermediate and final artifact analysis, with particular attention to the transitions between artifacts and the ways in which their making became part of the ongoing process; and 2) development of a methodological tool used to identify, map, and synthesize key events in order to discover patterns and collective insights that aided us in abstracting our process. In the visualization, lines represent different processes (digital fabrication, biofabrication, and craft-based making). Round images represent event activities in which these processes intertwine, and artifacts and iterations appear as square images and parenthetical notes to the right of the lines (Figure 4; also see the larger version, Figure A1).

Figure 4. The methodological tool maps key events by visualizing entanglements and their “knots.”

A larger version of this visualization is included in the Appendix (Figure A1).

The reconstruction process took place over the course of multiple team meetings, during which photographs and video footage were reviewed, as well as artifacts and tools integrated into discussions. Prior to these meetings, laboratory notes were analyzed for key concepts, including moments of noticing, process adaptations, and the introduction of new procedures (Figure A11). This allowed us to identify and “relive” central design events in the larger context of the completed project. In addition, the visualization tool guided us in identifying design events and the corresponding negotiations involved in their occurrence, while serving as a visual means of navigating entanglements.

Making Methods

In this research, our objective was to explore—both concretely and conceptually—the notion of growing tessellations: firstly, whether a conventionally folded or assembled structure could be grown through methods reliant on the contributions of diverse constituents; and secondly, how a close examination of the design process integrating these varied constituents might be abstracted to provide a framework for interdisciplinary designing.

We begin with brief background information about the project parameters, after which we present first-person perspectives of three design events excerpted from our process. These events were chosen as representative of the shared design process that characterized the project as a whole, and they are accompanied by a supplemental materials appendix that further documents our activities.

Project Parameters

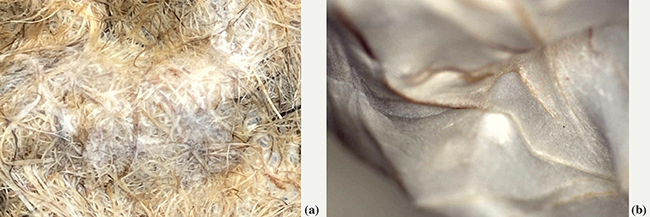

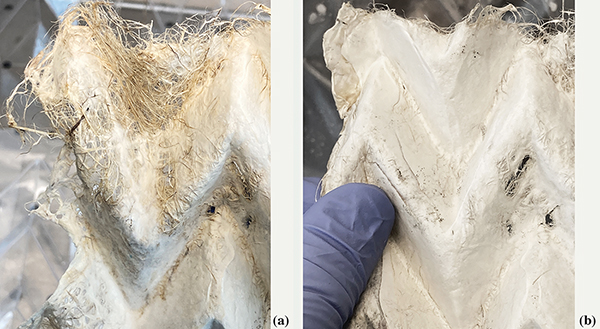

Mycelium consists of networked hyphae, which serve as the roots for fruiting mushrooms, and it is characterized by interlacing tendrils that produce a homogeneous—and surprisingly resilient—“fuzzy” white layer (Figure 5). In a laboratory setting, mycelium can be cultivated from mother cultures and introduced into substrate materials that provide it with the necessary nutrients. These mycelium-substrate composites can, in turn, be molded into desired shapes, providing myriad possibilities for design applications. Mycelium has been used to create modular blocks for building construction (Abdelhady et al., 2023), interior design tiles for decor and soundproofing (Karana et al., 2018), alternatives to leather (Amobonye et al., 2023), and protective packaging material (Madusanka et al., 2024), to name just a few recent case studies.

Figure 5. Mycelial root systems or hyphae:

(a) forming a white “fuzz” on carded hemp fibers, and (b) the same structure under the microscope.

The ability to shape mycelium, combined with its flexible structure when cultivated homogeneously, makes it a particularly well-suited material for growing dynamic tessellations. However, the choice was not purely mechanical. Aligning with the relational nature of affordances as materials potential (Barati & Karana, 2019), our unique backgrounds as practitioner-researchers played a crucial role—bringing together the knowledge and skills of working with mycelium in the lab as well as crafting with plant fibers and alternative sources of cellulose (an ideal substrate for mycelial growth). The intertwining of expertise enabled a prospective search for commonalities amongst materials, practices, media, and techniques that pushed beyond practitioners’ intuition. Taken together, the authors’ situated knowledge and the bridging role of mycelium allowed for a sharper analytical focus on emergent possibilities arising from the entanglement of our shared capabilities, materials included (c.f., Barati & Karana, 2019).

Different strains of mycelium exhibit diverse behaviors, and material benchmarking led to the selection of Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum) as our primary species. Reishi grows reliably in the laboratory (Stamets, 2005), bonds successfully with various substrate materials, including cellulosics (Sayfutdinova et al., 2022), and is amenable to structural manipulation (Cotter, 2014). In addition, as practice provided a foundation and condition-setting operation for this work, we selected two methods of creating mycelium composites that would be grown into tessellations: 1) papermaking with mycelium, which provided a strong connection to craft and human-driven efforts, and 2) molding natural cellulose fibers, which relied primarily on mycelial labor. For both methods, we selected the Miura tessellation, a relatively straightforward corrugation that nonetheless demonstrates enhanced kinematics and flat-foldability (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Miura examples: (a) structure folded from paper; (b) Reishi growth on fiber substrate.

Design Events

Our criteria for selecting events were as follows: 1) diverse processes becoming entangled into “knots”, 2) entanglement creating conditions with potential for processes to transcend their conventional capabilities, and 3) artifact(s) produced by the event reifying the notion of processes entangling. We believe that the three design events excerpted here represent the entangling of intentions and agencies (human and more-than-human) across the scope of the project. While these events are depicted separately, it is essential to note that processes and intermediary artifacts have impacts that extend beyond individual moments or stages: the nature of a living design process necessitates attention to the ongoing significance of each event.

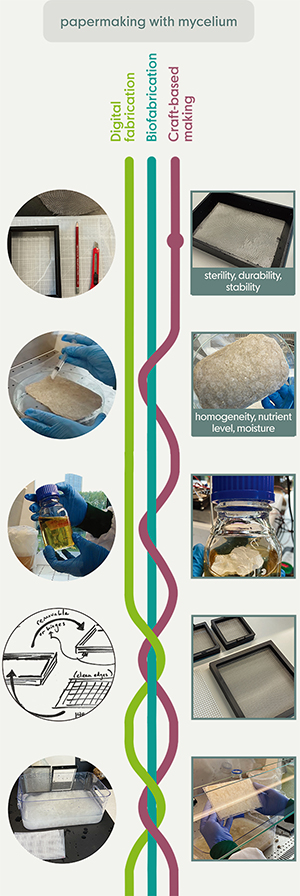

Papermaking with Mycelium

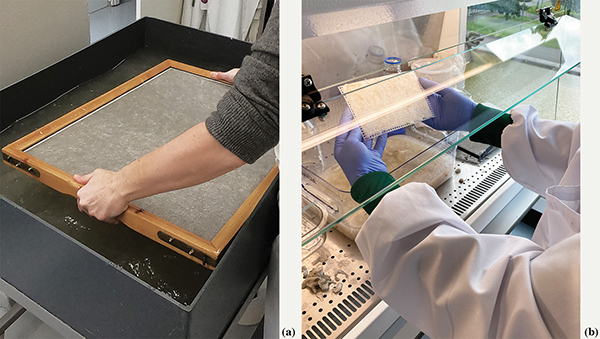

There is perhaps no better example of the benefits of combining (seemingly) disparate processes than papermaking with mycelium. Initial testing showed that prefabricated paper sheets inoculated with mycelium produced uneven growth, underscoring the need to create a homogeneous mixture of pulp and mycelium inoculant, as well as to adapt the papermaking process for mycelium. At the outset, we taught each other our respective crafts: trading expertise as we shared how to prepare mycelium mother cultures and inoculate substrate, and how to process cellulose pulp and pull paper sheets. However, entangling mycelium cultivation with papermaking posed numerous challenges from the start. Mycelium requires a sterile inoculation environment and is particularly sensitive to moisture during the growth stage. Laboratory inoculation takes place inside a contained ventilator, which maintains airflow while minimizing the possibility for contamination. Papermaking, on the other hand, tends to be an expansive process that flows freely between pulp beater, water basin, and press. Combining the two required a collective rethinking of conventional techniques, necessitating an approach—a negotiation—that could move beyond solely biofabrication or craft (Figure A5).

Within the larger design event, the first “knot” involved developing a solution for inoculation (Figure 7). After less successful attempts with mixing pre-prepared liquid mycelium into pulp, we chose to craft our own liquid inoculant, enabling us to address the requirements of both papermaking and our living material: specifically, achieving a condensed yet homogeneous distribution of inoculant and pulp in water, while responding to the mycelium’s need for additional nutrients in a high moisture environment.

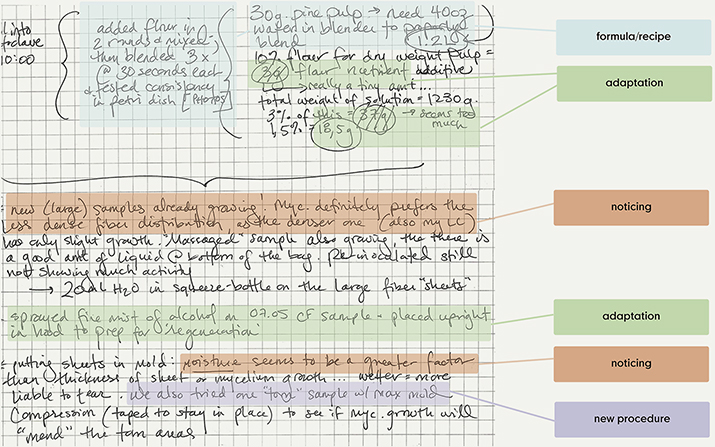

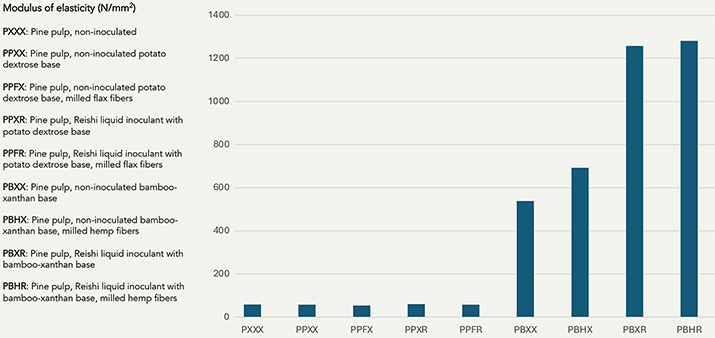

Figure 7. Papermaking event: closeup of the visualization tool.

After experimenting with potato dextrose and flour as potential nutrients, our final liquid medium consisted of seeds inoculated with a Reishi mother culture and a slurry made from bamboo fibers and xanthan gum. This proved to be fluid enough to thoroughly mix with cellulose pulp while remaining stable enough to concentrate the mycelium and nurture its growth. As we would later find, this negotiation between actors and processes also led to an unexpected “transcendence”, or the ability of entangled processes to move beyond their own isolated capabilities. Mechanical testing of our mycelium-paper tessellations demonstrated heightened elasticity and fracture toughness, as compared to non-inoculated sheets made under the same laboratory conditions (Figure A12; Figure A13).

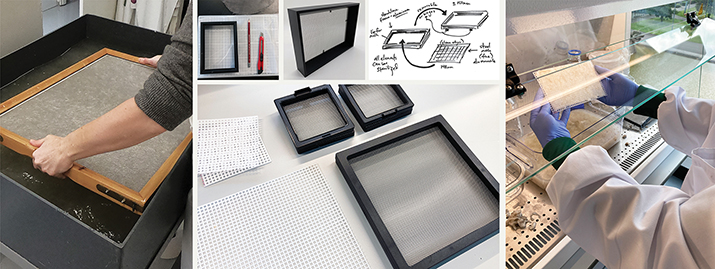

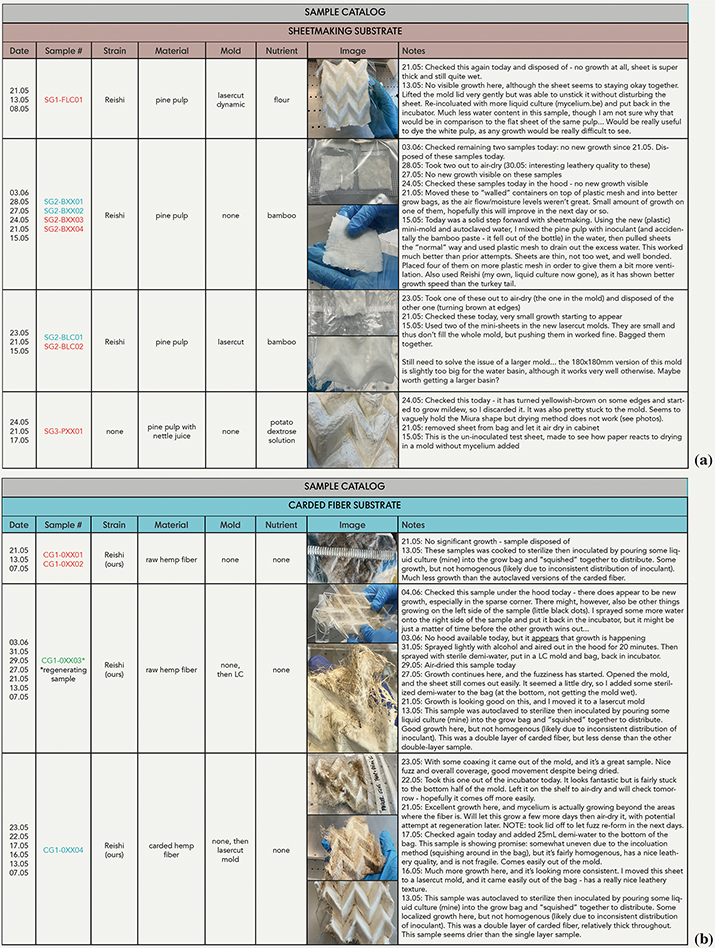

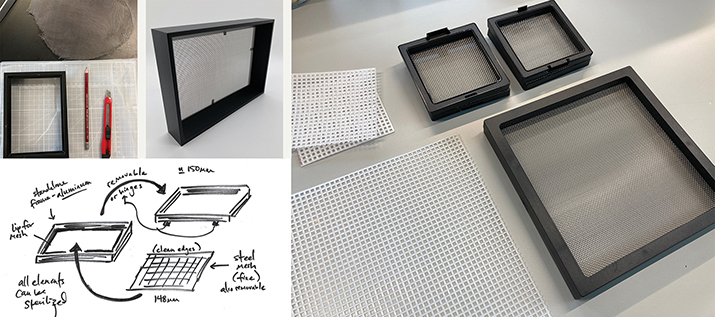

Our next step was to use the inoculated pulp to create sheets through which the mycelium would grow into tessellated structures. In papermaking, the mold and deckle are submerged in a diluted pulp-water mixture, resulting in a distribution of fibers that are drained and removed from the screen. These fibers are then pressed and dried to form sheets. Early prototypes of our mold and deckle for mycelium sheets utilized a traditional wooden frame and cloth mesh, as well as a pour-mold style construction (Figure A6). These efforts were guided by papermaking standards and reflected minimal biofabrication input. We soon discovered that the resulting sheets were not only too wet to support mycelium growth but also highly susceptible to contamination. In response, we speculated on the needs of mycelium and how we might better address them: the mold and deckle should be sterilizable to avoid contamination, deconstructable to ease the removal of newly-pulled sheets in a small workspace, and inclusive of a solution for mitigating excess water retention.

We then turned to digital fabrication to create a custom set of tools that met these concerns. Aluminum and stainless steel were used to construct a sterilizable mold and deckle that easily released the screen, allowing for the removal of pulled paper sheets. The deconstructed pieces could be cleaned and sterilized more efficiently, and a set of custom-cut polyethylene mesh sheets provided sterilizable surfaces that could be sandwiched to remove excess water. This assembly represents an instance where digital fabrication techniques merged with biofabrication and craft sensibilities, creating an entanglement that led to the development of new tools and techniques.

Preparing Bast Fiber Substrates

Numerous studies have shown that mycelium proliferates in natural plant fiber substrates (Cotter, 2014; Geris et al., 2023; Stamets, 2005), which guided our selection of bast fiber (industrial hemp) as a substrate material. Bast fibers are exceptionally long and resilient, and thus ideal for creating both durable textiles and paper with increased tensile strength (Abdelhady et al., 2023; Kääriäinen et al., 2020). Hemp in particular is also one of mycelium’s preferred substrate materials (Elsacker et al., 2019). The selection of industrial hemp for this purpose was therefore a negotiated choice: our combined knowledge of cellulose applications in craft and mycelial growth conditions, entangled with the importance of choosing a substrate that would give mycelium a chance to play a central and requisite role in the formation of tessellations (Figure 8). However, this negotiation was just the first of many that enabled the success of the substrate.

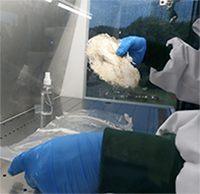

Figure 8. Bast fibers event: closeup of the visualization tool.

Our first iteration of preparing the fiber substrate involved shaping raw fibers into square “sheets”, boiling them for sterilization, then inoculating with a syringe of liquid medium—a standard procedure in biofabrication. The result, however, produced uneven mycelium growth that stalled after several days of incubation and showed signs of contamination. We then reflected on how we might utilize craft and alternative biofabrication techniques to better align with the needs of mycelium as a living material. Following a model of co-speculation (Wakkary & Oogjes, 2024), we reviewed our prior documentation and discussed potential conditions under which mycelium might respond best. The proposed solution involved three adaptations: 1) carding fibers prior to sterilization (a textile processing technique that unidirectionally brushes fibers while removing impurities); 2) autoclaving rather than boiling for sterilization, with careful iterations of measured water levels; and 3) using a manual massage technique to distribute the liquid inoculant. Each of these adaptations presents a “knot” or moment of negotiation within the larger design event.

As with papermaking, growing tessellations with hemp fiber substrates required a convergence of craft and biofabrication expertise. This design event captures a set of circumstances that we believe is integral to negotiation and transcendence: domain shifts that contribute to adopting openness and new perspectives, interconnected design events that collectively produce a living workflow, and production of intermediary artifacts that embody the actions of the design event. The fluidity and iterative/cumulative nature of these events, in our assessment, is what enabled the success of the “final” artifacts, or grown tessellations. However, equally significant are the intermediary artifacts themselves, as they not only represent entangled design events but also serve as tangible points of access for examining those entanglements.

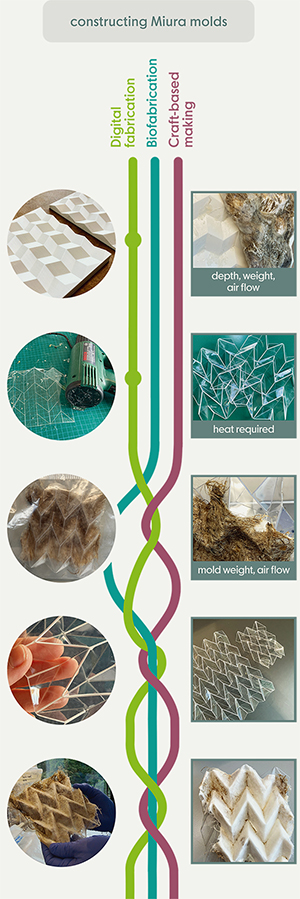

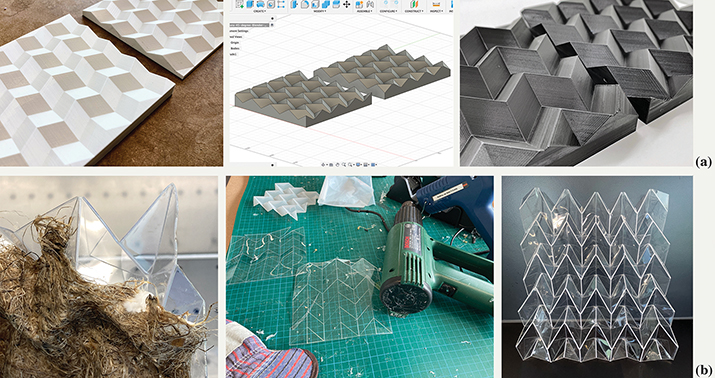

Constructing Tessellated Molds

In the project, constructing molds to form the Miura tessellations provided one of the richest opportunities for negotiating among actors and processes. Both inoculated paper sheets and carded fiber substrates were placed into the matrices we created, allowing the mycelium to grow into dynamic, three-dimensional tessellations. Digital fabrication techniques were invaluable for this process, and we utilized two types of matrix-style molds with conjoining top and bottom elements: 3D-printed molds made with PLA and laser-cut molds made with Vivak. The initial prototypes for each mold were created with standard digital fabrication guidelines in mind, including the preservation of material and optimization of the 3D printing process. It became clear, however, that the molds needed to be designed with input from both biofabrication and craft perspectives to produce amenable conditions for mycelium, as well as to support the tessellated structures we hoped to grow (Figure A8). Early 3D-printed molds were too light to press the growing mycelium sufficiently, and the Miura unit cells were overly shallow, inhibiting elasticity and dynamic growth in the resulting structures. Creasing the laser-cut Vivak into Miura patterns proved untenable unless thicker material and heat were applied, and the thicker material in turn suffocated mycelium growth. In the context of a shared design process, these “failures” were, in actuality, moments of opportunity to reflect on how tools, techniques, and perspectives could entangle, rather than forcing the considerations of one domain onto the others (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Molds event: closeup of the visualization tool.

This meant reassessing how we could utilize digital fabrication techniques in ways that would accommodate biofabrication and craft concerns, or performing reflection-based wayfinding. In the case of laser-cut molds, we ultimately selected an ultra-light Vivak material that was vector marked (a shallower laser-cutting technique) with the Miura crease pattern. With pre-creasing, these molds could be collapsed by hand into the Miura structure, and they not only remained dynamic, but were also capable of expanding or compressing to correspond with the mycelium’s preferences for air flow and moisture. Thus, the final laser-cut molds represent another instance of diverse domains entangling to transcend the capabilities of each on its own—as well as the vital role of noticing and negotiation in material entanglements.

In iterating the tessellated molds for mycelium, knowledge from digital fabrication, biofabrication, and craft-based making was invaluable. Digital fabrication skills provided a foundation for fluency with 3D printing and laser-cutting. However, expertise with bio-based materials brought clarity to the materiality aspect of the molds and mycelium’s needs and preferences in overly moist or too tightly sealed environments. Additionally, craft insights informed the creasing of Vivak into tessellated patterns, in which knowledge derived from origami practice enabled successful adjustments. Mold-making in this context thus transcended digital fabrication as a standalone process. Through the entanglement of processes, new types of dynamic molds were created, ideally suited for the biological needs of mycelium growth and the geometric precision of tessellated structures.

Discussion

We define and substantiate the concept of growing tessellations as the entanglement of diverse processes that, when combined, result in novel approaches to designing and making. Our conceptualization demonstrates how the conventional capabilities of each process—craft-based making, digital fabrication, and biofabrication—are transcended, leading to new insights and the creation of novel intermediary and final artifacts. This entanglement allows us to clearly observe and describe the negotiations of processes and practices, as well as the emergent properties that arise from such a drawing together (Ingold, 2014). By defining design events as knots formed from the intertwining of processual lines, we provide a tangible method of “untangling” these interactions and abstracting them at a conceptual level. Our analysis of the making process reveals that, alongside the development of interdisciplinary knowledge, new tools and techniques emerge, and the resulting artifacts capture these becomings. Artifacts serve as markers of a living design process, in which design is seen as an ongoing, fluid action (Ingold, 2014), with wayfinding guided by the interwoven influences of what has come before (Alexander, 2002b; Whitehead, 1979/1929). In other words, something becomes known only through its interaction with other things (Ståhl et al., 2022).

In the following sections, we discuss how this framework informs and expands our understanding of the negotiations that occur among various actors and processes in the act of designing-with. Furthermore, we propose that the combined forces of designing-with and practice-led research enable a new formulation of interdisciplinary design practice: namely, making-with. By delineating how interactions shape and transform the roles of both human and nonhuman makers, we propose that more-than-human collaborative making expands the notion of practice, allowing for innovation and insight. Additionally, we emphasize the importance of intermediary and final artifacts that prompt reflection—both as products of design events and as mediators for further action. We emphasize the emergent function of these artifacts as “boundary objects” (Star & Griesemer, 1989), as they embody the specificities of each process and the negotiations required to integrate them. Finally, we return to the notion of dynamic tessellations as a conceptual analogy for interdisciplinary design practice, underscoring the broader implications of our work. To this end, we discuss our visualization tool and draw on excerpts from the project’s extensive documentation and analyses (see Appendix) as concrete contributions toward supporting the transfer of knowledge to other practices and materials.

From Mediation to Negotiation

The maker’s role as a practitioner is often understood as one of mediation—carefully navigating techniques, skills, and materials to produce an outcome that is not entirely known at the outset (Adamson, 2007; Dormer, 1994). In conventional understandings of practice, the maker is ultimately “in control” of the process, although uncertainty and risk are inherent in collaborating with materials and tools (Pye, 1995/1968). Throughout this project, we aimed to move beyond conventional understandings of practice by integrating living materials and digital fabrication tools into our processes and responding to those non-human makers through reflection and negotiation. In other words, we set out to intertwine actors and processes, to tangle up the lines of what might be seen as disparate areas of inquiry. Negotiation, in line with Ingold’s (2013) argument that making should be a morphogenetic procession, is an opening up of feedback and dialogue amongst materials, tools, fabrication methods, and human and more-than-human actors. It can change these actors and shape ongoing processes, while respecting the characteristics and needs particular to each constituent. Successful negotiation is able to transcend the conventional capabilities of any one actor or process on its own, and this transcendence is what we sought to capture in our design events.

Noticing, Sympathizing, Opening

The act of negotiation shifts the emphasis from processes to necessarily considering actors. Whether human or more-than-human, actors are driven by an inherent purpose situated in their particular environs, histories, and intentions (e.g., Haraway, 2020). In simplified terms, mycelium requires a suitable environment in which to grow, and digital fabrication machines require precise codes and inputs with which to function. Entanglement, however, creates instances of interaction in which actors and their contexts tangle together: as lines, each retains its original form, but a collectively constructed knot emerges—a converging of paths rather than a merging of intentions—and this is where attention and noticing play a vital role (Tsing, 2015). In our work, the knots that comprise our design events embody this notion of noticing and adapting. Furthermore, in a living design process, the act of noticing and adapting makes space for the nodes of a “nested system of local symmetries”, each developing holistically from the other and resulting in a dynamic whole (Alexander, 2002b, p. 19).

Forms that entangle rather than assemble also allow room for a crucial step in the act of negotiation: empathizing. To notice is to observe the particularities relevant to each actor, and to sympathize is to recognize their value, whether it be techniques, tools, insights, or anything in between. Sympathizing creates a basis for domain shifts (Sennett, 2008), or what Tsing (2015) suggests can be productive cross-contamination—a necessary foundation for interdisciplinary work. Alongside noticing, sympathizing can produce a “deep-rooted engagement” (Spuybroek, 2016, p. 107) amongst diverse actors in a flat ontology, or a space in which work towards a common objective harmonizes otherwise disparate perspectives (Spuybroek, 2011). We view this harmonizing as a form of nudging that is requisite for negotiation and, ultimately, the revelation of novel affordances (Barati & Karana, 2019). The convergence of distinct processes such as craft, biofabrication, and digital fabrication illustrates the progression from line to knot, or from noticing to negotiating.

Implications for Designing-with

This unfolding of interactions is precisely how the design process should happen differently in the context of designing-with. The requisite steps of noticing, negotiation, and sympathizing, which we collectively refer to as wayfinding, provide a concrete method for unveiling novel affordances and pursuing a living design process in which each action is a holistic outgrowth of the actions that preceded it. When we see processes as lines, we experience their ability to intertwine and the effects of those entanglements. This aligns with the notion of viewing the world as a series of actions (Ståhl et al., 2022; Whitehead, 1979/1929), in which processes influence one another and insights emerge through interaction. As boundaries between processes blur, discoveries are made, and becomings are put into motion. Negotiation is then the unifying force behind artifacts, and designing clears the way for the design (Alexander, 2002b). An artifact is thus dependent not only on the events which led to its inception, but also on the negotiation through which it becomes. It is precisely this processual and reflexive approach that constitutes a more holistic approach to designing, or a living design process: one in which each actor and action (no matter how diverse) aligns to create a multifaceted whole, and their alignment in turn perpetuates that wholeness (Alexander, 2002b). This, then, is where the views of Alexander and Ingold align: the whole produced by a living process is an entanglement—a knot—that draws together disparate lines to define how something is made and what its making signifies for the greater whole.

Negotiation has implications for designing-with in that it inherently creates a shift away from human-centered perspectives in designing and making (e.g., Biggs et al., 2021; Loh et al., 2024; Nicenboim et al., 2025). Negotiation is not limited to reflection by the human designer, but rather opens the human designer to deeper dialogues with materials and processes from other domains, emphasizing attention rather than intention (Ingold, 2014; Tsing, 2015), and creating space for emergence as a basis of becoming (Aktas & Mäkelä, 2019). The act of negotiation becomes a catalyst for acknowledgement—and yet further, comprehension—of the value that non-human actors bring to a living design process, while providing a method of looking beyond human tendencies through tangible collaboration with diverse actors. In our case, growing tessellations is made possible through the discovery of novel affordances that transcend conventional capabilities, and this cannot be achieved without an equal recognition of the contributions of humans and non-humans alike.

Artifacts as Boundary Objects

The nature of a design event is that its origins form a prehension of actions which, synthesized together, return to an ongoing process in the form of artifacts and/or insights (Roberts, 2014; Whitehead, 1979/1929; Whitehead, 2022/1919). In our design events, individual processes could not act alone: artifacts were developed from the convergence of digital, biological, and craft-based insights, but those artifacts then went on to shape further processes. These artifacts both represent entanglement and promote further entanglements, and thus they can be characterized as boundary objects (Bowker & Star, 2000; Star & Griesemer, 1989).

Intermediate Artifacts

Tessellated molds, project diary entries, laboratory notes, constructed tools, and weekly reports: each represents a type of intermediate artifact that is both an object of entanglement and a fundamental contributor in the ongoing process of growing tessellations. Because these intermediaries are the result of negotiations, they provide tangible entities through which the entanglements of actors and processes can be observed and understood. In growing tessellations, these artifacts signify design events in which diverse processes came together—and thus moments with the potential to reveal novel affordances. Through analysis, their embedded learnings can return to the design process, serving as the origins of future events and intermediaries. Because they reflect the particularities of each actor who contributed to them, as well as achieve a “shared common identity” (Bowker & Star, 2000, p. 298), they operate as boundary objects.

Artifacts as Outcomes

Upon the project’s completion, we had developed a collection of tessellations using both mycelium paper sheets and carded fiber composites (Figure 10). While these outcomes serve as proof of concept for developing alternative methods of crafting tessellated structures, they also represent concrete manifestations of negotiations in design events. Yet further, each “final” artifact is a synthesis of entanglements in action, thus a boundary object in its own right.

Figure 10. Grown tessellations: artifacts with mycelium/hemp (top row) and mycelium/pine (bottom row).

We believe that these artifacts can be differentiated from intermediaries in that they facilitate boundary work, or the ability to generate knowledge at the boundaries between discovery processes and their outcomes (Elo, 2018; Rheinberger, 2018). In this sense, the “final” artifact is a necessary component in formulating concepts that may be abstracted to alter or develop design methods. Growing tessellations is a concept focused on the nature of designing, but grown tessellations allow for the emergence and concretization of that concept.

Implications for Interdisciplinary Research

In the introduction, we proposed that origami tessellations offer a conceptual analogy for the challenges designers face today. As dynamic structures, folded tessellations rely on both parametric inputs and emergent local behaviors, reflecting the complex work of designing as a shared process: one in which diverse constituents, techniques, and perspectives perform ongoing acts of negotiation. Tessellations in this context are themselves negotiations, and by introducing both living materials and digital fabrication into their development, we illuminate the negotiative exchanges inherent in domain-shifting practices. Our work, therefore, has direct implications for interdisciplinary design research on two levels: 1) providing a case for fostering negotiations in designing through reflection and analysis of intermediate and final artifacts, and 2) introducing a methodological tool developed during our process: a visualization of entanglements that can be applied to a broad range of cases (Figure A1).

In developing our visualization of entanglements, we focused on distinct process—craft-based making, biofabrication, and digital fabrication—as separate lines whose knots are manifested by intermediary and final artifacts. However, the applicability of this tool goes beyond the processes presented here and offers a relevant working method for the broad spectrum of interdisciplinary design-driven research. The diagramming of lines and knots provided us with a way of intentionally reflecting on the design process as it unfolded. By integrating elements of our documentation into the visualization (photos, sketches, iteration notes, etc.), we were able to actively identify design events and integrate the lessons learned from the artifacts produced along the way. Our “knots” served not only as progress markers, but they also became stimulating, occasionally challenging, and often joyful moments of acknowledgement and collaboration. Furthermore, in recreating our design process with the aid of this visualization tool, we were able to discern a circular progression illustrative of the living design process: 1) domain shifts lay the groundwork for design events, which were characterized by 2) entanglements of diverse actors with the potential to produce 3) boundary objects in the form of intermediary artifacts, which then returned to the 4) ongoing flow of events.

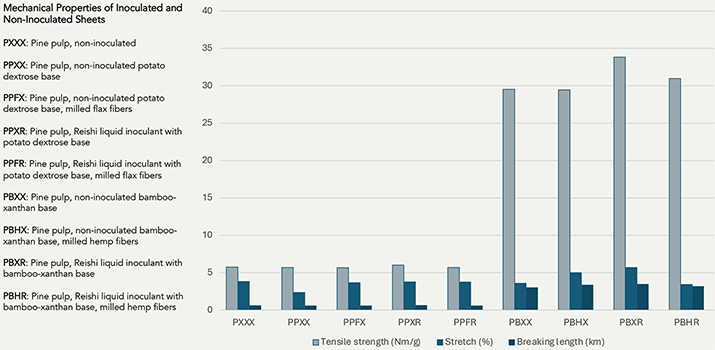

To further illustrate the connection between documentation, entanglements, and analysis within interdisciplinary design practice, we include an appendix that excerpts our documentation methods and results. In this way, the appendix is a vital part of our contribution, providing a guide for applying our framework to diverse cases of designing. From our positioning, we propose two points of entry for opening up and transcending in design practice: firstly, pursuing affordances of a specific type (in our case, growing rather than folding tessellations), and secondly, identifying and analyzing events that lead to affordances (the knots and entanglements presented in our visualization tool). The appendix provides concrete examples of both methods and thus serves as a model for how documentation can manifest an empirical yet fluid approach to process that enables novel affordances (Figure 11). By treating documentation as an intermediary artifact, it becomes an integral part of the living design process, creating a foundation for adapting the visualization tool to varied cases and circumstances.

Figure 11. Excerpts from the Appendix that illustrate the use of documentation as an artifact in itself.

By integrating holistic documentation methods into a living design process, events and their corresponding affordances can be identified and analyzed. Pictured here is the process of adapting papermaking for mycelium through the crafting of new tools as a response to mycelium’s needs and preferences.

Our objective in this project was to demonstrate a method of structured observation that nonetheless remained open to fluidity and emergence. While our shared expertise lies in specific areas of craft, biofabrication, and digital fabrication, the concept of “growing tessellations” transcends these domains by framing interdisciplinary design as a mesh in which key events entangle actors and processes with the potential to generate novel affordances. As such, “growing tessellations” provides a methodology for navigating interdisciplinary projects by identifying and bracketing events where the boundaries between craft, technology, and biology blur—regardless of the specific craft techniques, digital tools, or materials involved. It redefines expertise as fluid, context-dependent, and continually reshaped through negotiations among diverse processes and actors, both human and nonhuman. In doing so, it expands prevailing understandings of expertise in interdisciplinary contexts by proposing a mode of working in which negotiation provides a foundation for comprehending the needs and potential contributions of all constituents. These intertwinings, in turn, create conditions under which novel affordances can emerge.

Within the design discipline, there is a growing eagerness to pursue interdisciplinarity and explore more sustainable, bio-based materials. At the same time, designing-with proposes novel approaches to living materials and technologies as active participants (Giaccardi & Redström, 2020). In the work presented here, we synthesize practices relevant to both fields: biofabrication, digital fabrication, and craft-based making. We believe that practice-led research and designing-with have much to learn from each other (e.g., Aktas & Mäkelä, 2019; Lin et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2019). Together, their entanglements—in the form of making-with—demonstrate the potential to form collaborative design spaces with more-than-human actors, achieve innovations through transcendence of conventional capabilities, and produce dynamic artifacts that manifest the principles of negotiation.

Limitations and Future Work

The exploratory project presented here aimed to explore the synergies between practice-led research and designing-with, through the potentialities of tessellations as both concrete and conceptual structures. Our objective was to investigate an interdisciplinary design process as entangled, negotiative, and living. In doing so, we explored the viability of growing tessellations with mycelium composites rather than relying on conventional methods of folding or assembly. The planning and structure of the project allowed for preliminary exploration with the possibility of future expanded research. The objective was therefore not to provide comprehensive characterizations of the tessellated artifacts themselves, nor to conduct thorough experiential and qualitative testing. Rather, our focus was the development of methodological tools for interdisciplinary designing through event analysis, a visual means of entanglement, and reflection on our own practice. As a result, significant issues surrounding care and the implications of working with living materials (e.g., Camere & Karana, 2018; Groutars et al., 2024; Ooms et al., 2022), as well as the pursuit of technical innovation in fabricating tessellated structures, necessarily lie beyond the scope of this paper.

From an artifact characterization standpoint, many of our learnings warrant future research in grown tessellations—in particular, the feasibility of introducing more sustainable (bio-based) materials into the functionality of origami tessellations, the increased performance of mycelium as demonstrated by mechanical property testing (Figure A12; Figure A13), and the potential for structures that exhibit regenerative growth (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Regeneration: (a) air-dried mycelium composite; (b) new growth after re-incubation.

In terms of abstracting our concept of growing tessellations, we believe that the methods presented here can and should be applied in diverse design contexts, and that expanded use of the framework can reveal deeper insights about designing and collaborating with human and more-than-human constituents. Our visualization tool and documentation methods can, in turn, serve as a guide for mapping interdisciplinary projects with an emphasis on design processes that incorporate diverse perspectives and practices.

Conclusion

This paper presented the concept of growing tessellations with mycelium composites as a practicable framework for making-with in interdisciplinary contexts. Our objectives in pursuing this research were threefold: 1) to present a detailed account of our living design process combining biofabrication, digital fabrication, and craft-based making; 2) to investigate intermediary and final artifacts as boundary objects that both result from and engender acts of negotiation; and 3) to propose a methodological tool used to identify, map, and synthesize key events, actors, and processes. In the pursuit of these objectives, we proposed negotiation and the discovery of novel affordances as essential elements of a living design process. Our approach was informed by the theory of entanglement, as well as the concept of domain shifting. We employed Ingold’s terminology of meshwork, lines, and knots to clarify our understanding of design events. Within this meshwork, the processes of biofabrication, digital fabrication, and craft-based making provided lines to follow, with their convergences serving as events to untangle. By closely analyzing events through their subsequent intermediary artifacts, we identified a mode of wayfinding—noticing, sympathizing, nudging, and negotiating—through which the capabilities of any one given actor or process could be transcended. Indeed, it is the very nature of becoming as a series of negotiations that we argue is requisite for a reimagining of how we go about designing with diverse actors, practices, and techniques.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the Aalto University Bioinnovation Center, which was established by a grant from the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation. Additionally, the authors would like to personally thank the Bioinnovation Center Doctoral School at Aalto University, as well as the Industrial Design Department and Material Aesthetics Lab at Eindhoven University of Technology, for their support and encouragement throughout the project.

References

- Abdelhady, O., Spyridonos, E., & Dahy, H. (2023). Bio-modules: Mycelium-based composites forming a modular interlocking system through a computational design towards sustainable architecture. Designs, 7(1), Article 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs7010020

- Adamson, G. (2007). Thinking through craft. Berg. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350036062

- Akama, Y., Light, A., & Kamihira, T. (2020). Expanding participation to design with more-than-human concerns. In Proceedings of the 16th participatory design conference (pp. 1-11). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3385010.3385016

- Aktas, B., & Mäkelä, M. (2019). Negotiation between the maker and material: Observations on material interactions in felting studio. International Journal of Design, 13(2), 55-67. https://doi.org/10.57698/v13i2.05

- Alexander, C. (2002a). The nature of order: The phenomenon of life. Center for Environmental Structure.

- Alexander, C. (2002b). The nature of order: The process of creating life. Center for Environmental Structure.

- Amobonye, A., Lalung, J., Awasthi, M. K., & Pillai, S. (2023). Fungal mycelium as leather alternative: A sustainable biogenic material for the fashion industry. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 38, Article e00724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2023.e00724

- Andersen, K., Goveia da Rocha, B., Tomico, O., Toeters, M., Mackey, A., & Nachtigall, T. (2019). Digital craftsmanship in the wearable senses lab. In Proceedings of the international symposium on wearable computers (pp. 257-260). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3341163.3346943

- Andersen, K., Wakkary, R., Devendorf, L., & McLean, A. (2019). Digital crafts-machine-ship: Creative collaborations with machines. Interactions, 27(1), 30-35. https://doi.org/10.1145/3373644

- Ávila, M. (2022). Designing for interdependence: A poetics of relating. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Barati, B., Giaccardi, E., & Karana, E. (2018). The making of performativity in designing [with] smart material composites. In Proceedings of the conference on human factors in computing systems (Article No. 5). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173579

- Barati, B., & Karana, E. (2019). Affordances as materials potential: What design can do for materials development. International Journal of Design, 13(3), 105-123. https://doi.org/10.57698/v13i3.07

- Bardzell, J., Bardzell, S., Dalsgaard, P., Gross, S., & Halskov, K. (2016). Documenting the research through design process. In Proceedings of the conference on designing interactive systems (pp. 96-107). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2901790.2901859

- Bell, F., Chow, D., Lazaro Vasquez, E. S., Devendorf, L., & Alistar, M. (2023). Designing interactions with kombucha scoby. In Proceedings of the international conference on tangible, embedded, and embodied interaction (Article No. 65). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3569009.3571841

- Bhardwaj, A., Rahman, A. M., Wei, X., Pei, Z., Truong, D., Lucht, M., & Zou, N. (2021). 3D printing of biomass-fungi composite material: Effects of mixture composition on print quality. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 5(4), Article 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp5040112

- Biggs, H. R., Bardzell, J., & Bardzell, S. (2021). Watching myself watching birds: Abjection, ecological thinking, and posthuman design. In Proceedings of the conference on human factors in computing systems (Article No. 619). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445329

- Bowker, G. C., & Star, S. L. (2000). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences. MIT Press.

- Breed, Z., van der Putten, P., & Barati, B. (2024). Algae alight: Exploring the potential of bioluminescence through bio-kinetic pixels. In Proceedings of the conference on designing interactive systems (pp. 1412-1425). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3643834.3660728

- Camere, S., & Karana, E. (2018). Fabricating materials from living organisms: An emerging design practice. Journal of Cleaner Production, 186, 570-584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.081

- Candy, L., & Edmonds, E. (2018). Practice-based research in the creative arts: Foundations and futures from the front line. Leonardo, 51(1), 63-69. https://doi.org/10.1162/leon_a_01471

- Chang, Z., Ta, T. D., Narumi, K., Kim, H., Okuya, F., Li, D., Kato, K., Qi, J., Miyamoto, Y., & Saito, K. (2020). Kirigami haptic swatches: Design methods for cut-and-fold haptic feedback mechanisms. In Proceedings of the conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1-12). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376655

- Chen, T., Panetta, J., Schnaubelt, M., & Pauly, M. (2021). Bistable auxetic surface structures. ACM Transactions on Graphics, 40(4), Article 39. https://doi.org/10.1145/3476576.3476583

- Chen, Y., & Pschetz, L. (2024). Microbial revolt: Redefining biolab tools and practices for more-than-human care ecologies. In Proceedings of the conference on human factors in computing systems (Article No. 707). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3613904.3641981

- Cotter, T. (2014). Organic mushroom farming and mycoremediation: Simple to advanced and experimental techniques for indoor and outdoor cultivation. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Dalsgaard, P., & Halskov, K. (2012). Reflective design documentation. In Proceedings of the designing interactive systems conference (pp. 428-437). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2317956.2318020

- Davis, E., Demaine, E. D., Demaine, M. L., & Ramseyer, J. (2013). Reconstructing David Huffman’s origami tessellations. In Proceedings of the international design engineering technical conferences and computers and information in engineering (Article No. 12710). ASME. https://doi.org/10.1115/detc2013-12710

- Devendorf, L., Arquilla, K., Wirtanen, S., Anderson, A., & Frost, S. (2020). Craftspeople as technical collaborators: Lessons learned through an experimental weaving residency. In Proceedings of the conference on human factors in computing systems (Article No. 691). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376820

- D’Olivo, P., & Karana, E. (2021). Materials framing: A case study of biodesign companies’ web communications. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 7(3), 403-434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2021.03.002

- Dormer, P. (1994). The art of the maker. Thames & Hudson.

- Dunin-Woyseth, H., & Michl, J. (2001). Towards a disciplinary identity of the making professions: The Oslo millennium reader. Research Magazine, 4, 1-20.

- Elo, M. (2018). Ineffable dispositions. In M. Schwab (Ed.), Transpositions: Aesthetico-epistemic operators in artistic research (pp. 281-296). Leuven University Press. https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461662538.ch16

- Elsacker, E., Vandelook, S., Brancart, J., Peeters, E., & De Laet, L. (2019). Mechanical, physical and chemical characterisation of mycelium-based composites with different types of lignocellulosic substrates. PLoS One, 14(7), Article e0213954. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213954

- Elsacker, E., Zhang, M., & Dade-Robertson, M. (2023). Fungal engineered living materials: The viability of pure mycelium materials with self-healing functionalities. Advanced Functional Materials, 33(29), Article 2301875. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202301875

- Felton, S., Tolley, M., Demaine, E., Rus, D., & Wood, R. (2014). A method for building self-folding machines. Science, 345(6197), 644-646. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1252610

- Feng, S., Ta, T. D., Huang, S., Li, X., Koyama, K., Wang, G., Yao, C., Kawahara, Y., & Narumi, K. (2024). Rapid fabrication of haptic and electric input interfaces using 4D printed origami. In Proceedings of the conference on human factors in computing systems (Extended abstracts, Article No. 277). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3613905.3651022

- Fossdal, F. H., Nguyen, V., Heldal, R., Cobb, C. L., & Peek, N. (2023). Vespidae: A programming framework for developing digital fabrication workflows. In Proceedings of the conference on designing interactive systems (pp. 2034-2049). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596106

- Frayling, C. (2012). On craftsmanship: Towards a new Bauhaus. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Gaver, W., Krogh, P. G., Boucher, A., & Chatting, D. (2022). Emergence as a feature of practice-based design research. In Proceedings of the conference on designing interactive systems (pp. 517-526). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3532106.3533524

- Genç, Ç., Launne, E., & Häkkilä, J. (2022). Interactive mycelium composites: Material exploration on combining mushroom with off-the-shelf electronic components. In Proceedings of the Nordic conference on human-computer interaction (Article No. 19). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3546155.3546689