Value-Sensitive Design Generation with Stakeholders for Perinatal Life Support Development

Juliette Stephanie van Haren 1,*, Angret de Boer 2,3, Jan Heyer 4, Katie Verschueren 1, Tamara Hoveling 1, Marlou Monincx 1, Rooske van Loon 1, Emma L. Reiling 1, Sylvia A. Obermann-Borst 5, Panos Markopoulos 1, Rosa Geurtzen 3, Mark Schoberer 6, E. Joanne T. Verweij 2, Frank L. M. Delbressine 1, and M. Beatrijs van der Hout-van der Jagt 1,7

1 Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, the Netherlands

2 Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands

3 Radboudumc, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

4 RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany

5 Care4Neo, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

6 RWTH Uniklinik Aachen, Aachen, Germany

7 Maxima Medisch Centrum, Veldhoven, the Netherlands

Artificial Placenta and Artificial Womb (APAW) technologies are being developed to improve outcomes for extremely premature infants. Before such technology can be advanced to human trials, disparate challenges need to be addressed, spanning from technological issues that are addressed through functional prototypes to implementation challenges that require the definition of suitable procedures, as well as ethical issues for which public awareness and engagement are necessary. To involve future users and other stakeholders in the design process, we use a value-sensitive design approach. We advocate for an integrated approach that combines insights from the medical and technical fields with those from medical ethics, parent advocacy groups, and public opinion. Using a tripartite methodology, combining non-functional design prototypes, surveys, and (focus group) interviews, we collect a list of concerns, values, preferences, and design prerequisites. Values discussed included those related to safety, a nurturing environment, monitoring and intervention, parent-infant bonding, family-integrated care, and visceral aspects. Our results highlight how stakeholder involvement can make values more explicit and help formulate design requirements, as well as steer design processes. Our study demonstrates how applying a value-sensitive design process throughout APAW technology development enables stakeholder involvement to address implicit user needs, such as affective needs, early in the technology development.

Keywords – Artificial Womb, Extra-uterine Life Support, Parent-infant Bonding, Participatory Design, Value Sensitive Design.

Relevance to Design Practice – This study demonstrates a value-sensitive design method to collect stakeholder perspectives on novel life support technologies for premature infants.

Citation: van Haren, J. S., de Boer, A., Heyer, J., Verschueren, K., Hoveling, T., Monincx, M., van Loon, R., Reiling, E. L., Obermann-Borst, S. A., Markopoulos, P., Geurtzen, R., Schoberer, M., Verweij, E. J. T., Delbressine, F. L. M., & van der Hout-van der Jagt, M. B. (2025). Value-sensitive design generation with stakeholders for perinatal life support development. International Journal of Design, 19(3), 121-140. https://doi.org/10.57698/v19i3.06

Received January 8, 2025; Accepted July 31, 2025; Published December 31, 2025.

Copyright: © 2025 van Haren, de Boer, Heyer, Verschueren, Hoveling, Monincx, van Loon, Reiling, Obermann-Borst, Markopoulos, Geurtzen, Schoberer, Verweij, Delbressine, & van der Hout-van der Jagt. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-access and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: j.s.v.haren@tue.nl

Juliette van Haren is an assistant professor in the Industrial Design Department at Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands. She holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in (neuro)biology and a Ph. D. in industrial design. Her research interests involve designing for human and planetary health. She currently researches the development of life support technologies through value-sensitive design methods.

Angret de Boer is a Ph. D. candidate in obstetrics and neonatology at the Leiden University Medical Center and the Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands. She holds a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in medicine. Her research focuses on decision-making at the limit of viability and the (ethical) perspectives on the development of artificial amniotic and placenta technology.

Jan Heyer is a Ph. D. candidate in Mechanical Engineering at the Institute of Applied Medical Engineering, Dept. of Cardiovascular Engineering, RWTH Aachen University. He holds a bachelor’s and master’s degree in Mechanical Engineering and a master’s degree in Economic Sciences. Jan’s research interests include medical cardiovascular technologies for neonates and children. He is currently researching the approach of an Artificial Womb and Placenta for neonates from 24 to 28 weeks of gestational age.

Katie Verschueren graduated with a master’s in Industrial Design from the Eindhoven University of Technology. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Communication & Multimedia Design. Her research interests include designing for healthcare topics. Her current research interests range from design for people with dementia to design for the well-being of students while focusing on human-centred design and participatory design methods.

Tamara Hoveling was a master’s student in the Industrial Design Department at Eindhoven University of Technology. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Product Design and a Master’s degree in Constructive Design Research. Tamara’s research interests include clinical innovation and sustainable healthcare. She is currently a Ph. D. candidate at Delft University of Technology, researching the design of medical devices for a circular economy.

Marlou Monincx is an MSc graduate from the Industrial Design Department at the Eindhoven University of Technology. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Product Design. Her research interests include healthcare-based design topics, including the artificial womb and sustainable healthcare devices. She is interested in working in the design field to create devices that solve healthcare challenges within hospitals.

Rooske van Loon is an MSc graduate from the Industrial Design Department at Eindhoven University of Technology.

Emma Reiling is an MSc graduate from the Industrial Design program at Eindhoven University of Technology. She also holds a bachelor’s degree in Food Technology. Emma is currently working as a product owner at a company specializing in IT solutions for healthcare professionals.

Sylvia Obermann-Borst is the director of Science and Care at Care4Neo, a Dutch parent and patient association dedicated to supporting families with prematurely born, low birth weight, or ill infants.

Panos Markopoulos is a full professor in the Industrial Design Department at Eindhoven University of Technology. He is currently working on ambient intelligence, behavior change support technology, sleep quality monitoring, end-user development, interaction design, and wearable rehabilitation technology for children.

Rosa Geurtzen is a pediatrician and neonatologist at the Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Her research interests focus on complex decision-making in neonatal care.

Mark Schoberer is a senior neonatologist and pediatric intensive care physician at RWTH Aachen University Hospital. He is a private lecturer in pediatrics. His particular research interests are technological solutions for the protection of preterm infants.

Joanne Verweij is a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands. Her research interests focus on maternal-fetal medicine and perinatal ethics.

Frank Delbressine is an assistant professor in the Industrial Design Department at Eindhoven University of Technology. He has a background in mechanical design, engineering, and manufacturing. His research interests are medical simulation and smart mobility.

Beatrijs van der Hout is a medical engineer for the Obstetrics Department at Máxima Medisch Centrum. She holds a bachelor’s degree in both midwifery and biomedical engineering, a master’s degree, and an EngD in (qualified) medical engineering and a Ph.D. degree in electrical engineering. Beatrijs’ research interests include fetal-maternal monitoring, fetal physiology, and mathematical simulation thereof. She is currently researching the development of liquid-based incubation for extremely premature infants.

Introduction

Current medical treatment for extremely premature infants, born before 28 weeks of gestational age (GA), involves intensive care such as respiratory support and enteral feeding. Despite these efforts, the mortality and morbidity rates for these infants remain high due to the fragile and underdeveloped nature of their organs (Morgan et al., 2022; Patel, 2016). The investigation of extracorporeal life support, known as the artificial womb (AW), has been a subject of study since the 1950s (Greenberg, 1955; Westin et al., 1958). This technology aims to extend organ maturation within an environment resembling the womb. This approach entails maintaining the infant in a fetal physiological state, with the lungs immersed in amniotic fluid, and sustaining a fetal blood circuit through the umbilical vessels using an artificial placenta (AP) (van der Hout-van der Jagt et al., 2022). Advances in creating a liquid-based environment, sustaining fetal circulation, and ensuring physiological placental blood flow have given rise to optimism that clinical application will soon be feasible. With human trials now under consideration (Kozlov, 2023), the methods proven effective in animal studies should be adapted to suit human patients.

The core concept of APAW systems is to mimic the native situation as closely as possible to benefit the infant’s development (van der Hout-van der Jagt et al., 2022). This concept, of a liquid-filled environment, necessitates distinct design features and scenarios compared to conventional neonatal incubators. Potential design-related differences with current incubators may include the presumed limited direct parent-infant interaction, altered roles for parent access to the incubator, altered roles for clinicians, and different use scenarios for monitoring and intervention.

Previous studies on APAW technology have examined it from multiple perspectives, such as fetal physiology (van der Hout-van der Jagt et al., 2022), the needs of parents and clinicians (van Haren et al., 2023), societal (Nabuurs et al., 2023), and ethical considerations (Krom et al., 2023; Verweij et al., 2021). These perspectives affect the prerequisites for a system’s functionalities, monitoring needs, and staff involvement. In preclinical studies, the focus of existing technological setups has primarily been on addressing immediate life-support needs, as well as the technical and clinical validation of the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of mimicking fetal cardiovascular physiology. Meanwhile, exemplars from the Design field have typically focused on experiential needs. Yet, they lack a foundation in current scientific evidence (Usuda et al., 2022) and thereby fail to steer the direction of current innovations. The field lacks contributions that simultaneously address clinical, technical, and experiential needs.

As previously argued by Verweij et al. (2021), an integrated approach is needed, where insights from the medical and technical fields are combined with those from medical ethics, parents (of extremely premature infants), parent advocate groups, and public opinion. The connection between technical, medical, and patient requirements, on the one hand, and parental and societal values, on the other hand, has not been described and integrated from a design perspective in APAW research before. This study focuses on the process of stakeholder involvement by collecting (design) requirements through a value-sensitive design approach. Where co-design, co-creation, and participatory design focus on stakeholder collaboration throughout the design process, value-sensitive design emphasizes a structured approach to embed these values explicitly in the technology’s design. Using value-sensitive design methods enables the prioritization and alignment of diverse stakeholder values, promoting responsible outcomes and technology acceptance among its intended user groups. We employed a tripartite methodology that combines conceptual, empirical, and design investigations iteratively (Friedman & Hendry, 2019). The design concept sketches and prototypes presented in this study aim to explore the potential implications of new technologies, identify overlooked aspects, engage stakeholders, and ultimately guide the development of preferable futures, rather than merely serving as functional prototypes. Using prototypes helps to identify the difference between what people say they do or value (declared practices) and what people actually do or value when they see or use a prototype (real practices), also known as theory-in-use (Friedman & Hendry, 2019). Therefore, this approach encourages participants to reflect on (physical) attributes and experiential needs that might previously have been unarticulated, and to provoke cognitive reactions that can be further explored (Forlizzi et al., 2003; Norman, 2004). They may help reveal new opportunities and potential tensions between stakeholders, such as parents and clinical staff.

This study applies value-sensitive design methods to the challenging domain of APAW technology development to elicit insights of both direct and indirect stakeholders.

Background

Sensorial Development

In utero, the development of the sensory system relies significantly on natural sensory stimuli (Clark-Gambelunghe & Clark, 2015). Therefore, sensorial development may benefit from enabling interaction with the infant and allowing various stimuli–such as maternal physiological sounds, external sounds, maternal movements, uterine contractions, and diurnal rhythm, whether simulated, pre-recorded, or real-time–to reach the infant (van der Hout-van der Jagt et al., 2022). Despite advances in neonatology practices, premature infants in the NICU are still exposed to some unfiltered sensory experiences (Lickliter, 2011). While the long-term cognitive and perceptual impacts of these changes are not fully understood, research suggests that this altered sensory environment can have lasting effects on the development of the premature brain (Gressens et al., 2002).

Neural circuits and nociceptors involved in touch are the earliest to form during prenatal development (Marx & Nagy, 2017; Salihagić Kadić & Predojević, 2012). By the seventh week of GA, various skin sensory receptors develop, covering the entire skin surface by the 20th week (Salihagić Kadić & Predojević, 2012). Functional connections link the spinal cord to the brain between the 20th and the 24th week (André et al., 2018). During these stages of development, the fetus can sense pain (Salihagić Kadić & Predojević, 2012), respond to passive touch stimuli such as pressure applied to the mother’s abdomen (Marx & Nagy, 2017), or respond to vibroacoustic stimulation (Kisilevsky et al., 1992).

At approximately 25 weeks of GA, the auditory system permits fetuses to perceive sounds (Graven, 2000). Despite the protective function of amniotic fluid against harsh sounds, the uterus is far from silent, and the exposure to sound is important for fetal development (Graven & Browne, 2008a; Krueger et al., 2012; Panagiotidis & Lahav, 2010; Philbin, 2017). Fetuses can perceive a mother’s voice (Krueger, 2010) and maternal intra-abdominal sounds, including heartbeat and the flow of blood (Panagiotidis & Lahav, 2010; Philbin, 2017). Excessive noise exposure may have detrimental effects on cardiovascular and behavioral function, thereby harming neurodevelopment (Brown, 2009; McMahon et al., 2012; Morris et al., 2000; Vincens & Persson Waye, 2022; Williams et al., 2009). Recommendations could be based on current NICU guidelines to avoid long-term exposure to low-frequency sound (<250Hz) and to prevent exceeding dB levels above 50dB (Graven, 2000; Philbin, 2008; Philbin & Evans, 2006).

The vestibular system is responsible for the sense of balance, position, and spatial orientation, and can be recognized by the sixth week of GA (Jouen & Gapenne, 1995). Research showed that the labyrinth’s shape of the vestibular system stops changing after 17-19 weeks of GA (Jeffery & Spoor, 2004). However, there is a lack of literature data on the functional development. Factors triggering this system include maternal movements (i.e., walking), which enable infants to prepare for maintaining balance (Besnard et al., 2018; Lickliter, 2011; Salihagić Kadić & Predojević, 2012). Although alterations in direction, force of gravity, and rotation have been shown to influence the prenatal development of the vestibular system, no safe threshold ranges have been identified in the literature that can serve as a guide.

The visual sensory system is developed at approximately 24 weeks of GA with a first pupil reflex at 30 weeks (Hazelhoff et al., 2021; O’Connor et al., 2007). Inside the womb, some light may permeate through the human skin, providing optimal conditions for the visual system to gradually prepare for visual experiences following birth (Magoon, 1981; Reid et al., 2017). Harsh light directly hitting the infant’s eyes is generally avoided for extremely premature infants, since their eyelids are still transparent, allowing ambient light to pass through (Fielder et al., 1988; Graven & Browne, 2008b; Rodríguez & Pattini, 2016).

Gustatory chemosensory circuits become functional around 17 weeks, and olfactory circuits at 24 weeks of GA (Lipchock et al., 2011), with taste buds being involved in stimulating swallowing. The maternal diet is transmitted via volatile chemicals to the amniotic fluid and can therefore be experienced by the fetus (Lipchock et al., 2011). Chemosensory continuity, both prenatally and postnatally (e.g., via amniotic fluid), may help stabilize the emotional state of premature infants (Schaal et al., 2004).

Bonding and Well-Being

Compared to current premature infant care, the APAW system is a physical barrier and, by nature, restricts parent-infant contact. Since it functions as a life-sustaining environment, this barrier cannot be temporarily removed or overcome. From the infant’s perspective, being placed in a liquid-based incubator means that superficial sensory contact with the mother is entirely inhibited, and other sensory perceptions are significantly restricted. The infant is in contact with a technical surface rather than the usual biological tissues as an interface to the mother’s body. This highlights the need for design (and technology) efforts to increase the ‘permeability’ of the surface, to enable possibilities for reciprocal interaction with the environment.

Psychological research on premature infants indicates that separation from the mother after birth can lead to insecure attachment patterns, increasing the risk of mental disorders, addiction, and antisocial behavior in these infants (Mehler et al., 2023). Inadequate bonding in extremely premature infants may adversely impact their hormonal, epigenetic, and neuronal development (Kommers et al., 2016). The first hours post-birth are crucial for attachment in premature infants, with mothers who see their infants within 3 hours being more likely to establish secure attachment (Mehler et al., 2011). Additionally, direct skin-skin contact in the delivery room has been shown to significantly reduce postpartum depression in mothers (Mehler et al., 2020). Parent-infant physical and emotional closeness is crucial for the infant’s social, cognitive, and physical development, as well as maternal outcomes and adjustment to the parental role, which in turn benefits the infant’s development (de Cock et al., 2016; Flacking et al., 2012; Joas & Möhler, 2021).

NICU environments, filled with unfamiliar elements, increase parental stress, often diverting the parents’ focus from the infant to the NICU itself during early preterm care (Aagaard & Hall, 2008). Providing emotional support, clear information, and involving parents in their infant’s care helps improve their confidence and effectiveness as parents (Cleveland, 2008; Obeidat et al., 2009). The field of neonatology has learned the importance of parental involvement, leading to ongoing adaptations in medical standards, procedures, and treatment environments that are tailored to these insights. In current care methods, it is recommended to ensure the bonding, thereby promoting the well-being of both the parent and the infant (World Health Organization, 2022). These interventions include kangaroo care and the Newborn Individualized Development Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) (Kleberg et al., 2007). Kangaroo care has been shown to stabilize oxygen levels and body temperature (Head, 2014), improve weight gain (Evereklian & Posmontier, 2017), and improve neurodevelopment (Head, 2014). On the part of parents, it is shown to enhance their confidence and competence in a parental and caring role (Mu et al., 2020). Skin-to-skin care promotes oxytocin release, thereby preventing postpartum hemorrhage, supporting uterine involution, lactation, parental attachment, and reducing postpartum depression (Saxton et al., 2015; Walter et al., 2021). During pregnancy, a mother experiences the fetus as part of her being, with fetal movements allowing her to feel and monitor the unborn child’s well-being. Having given birth but being separated from the child and deprived of the role as primary caregiver can induce traumatic feelings of loss, guilt, helplessness, anxiety, and grief, with depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms being common in preterm parenthood (Gökçe İsbir et al., 2023; Mehler et al., 2020). This highlights the importance of early, consistent, and thorough parental involvement in the care of the preterm newborn. Family-integrated care practices promote this approach and engage family caregivers in the daily care of their hospitalized infants, which may also foster bonding (O’Brien et al., 2018; Soni & Tscherning, 2021).

Design Landscape

Design research, specifically interaction design, can extend its considerations to include the previously described neurodevelopment and bonding, aiming to support both the infant’s sensory development needs and the parent’s bonding needs (Schrauwen et al., 2018). Research on APAW has predominantly focused on technical and clinical validation. The technical experimental set-ups of these systems reflect this and consist mainly of the following essential components: a liquid-containing bag, an artificial placenta, a cannula connecting to the umbilical vessels, tubing for fluid supply and drainage, and a dialyzer (De Bie et al., 2021). Meanwhile, on the other side of the spectrum, speculative and artistic artificial womb designs, although predominantly aimed at full ectogenesis rather than partial, emphasized experiential aspects. Examples include the Par-tu-ri-ent (Minkiewicz et al., 2017), the wearable system Cybele (Iqbal, 2017), and the exteriorized womb-like balloons by Next Nature Network (Grievink, 2018). No design exemplars have been published that simultaneously address clinical, technical, and experiential needs.

Within the field of AP technology, researchers are also exploring a liquid-filled-lung approach, an alternative to full-body immersion (Church et al., 2018; Schoberer et al., 2012; van der Hout-van der Jagt et al., 2022). This method involves using a liquid-filled cuffed endotracheal tube to keep the preterm infant’s lungs fluid-filled, thereby still allowing for direct contact between care providers and parents with the infant, similar to present preterm care practices. Our current study, however, examines APAW technology, which involves full-body immersion.

While conventional neonatal incubators also establish a physical barrier, parent-infant interaction remains possible to a certain extent; infants may be held by their parents, the incubator itself allows for touching or close-up viewing, or remote observation via camera when parents are absent. The incubators, initially designed for newborn thermal care, have evolved into highly technological devices with peripheral technologies such as ventilators, circulators, pumps for medication/nutrient supply, phototherapy lights, and sensors and displays for physiological monitoring (Ferris & Shepley, 2013). The basic architecture of the incubator has remained largely unchanged, while improvements have been made by mitigating external stress, facilitating some parent involvement, and thereby enabling developmentally supportive care (Antonucci et al., 2009; Ferris & Shepley, 2013). ISO standards exist for components of infant incubators, as well as for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Recently, a standard of care for NICU design has been developed to support high-quality, family-centered care optimally (Moen et al., 2018). Some projects have adopted a patient-centered and neuroprotective NICU design approach, like the Wee Care and LOTUS projects by Philips Healthcare (Altimier et al., 2015). This design aims to reduce external disruptions between the infant and the NICU environment. Hybrid incubators are increasingly becoming the standard of care in high-resource NICUs. With a removable upper lid, they can function as either incubators or warming cots, providing both thermal regulation and easy access to the infant. This transformation is reversible and can be achieved within seconds.

Sensory-based interventions in the NICU have shown positive effects on infant outcomes (Pineda et al., 2023). Design systems that can capture and release the recorded sensory signals to allow for indirect but mediated contact have also been described. While there is considerable enthusiasm around sensory-based interventions, many studies provide only circumstantial evidence of their assumed beneficial effects on infants. Several studies recorded maternal heartbeats, abdominal sounds, and voices using microphones or electronic stethoscopes, and replayed them in the incubator (Liu et al., 2008; Panagiotidis & Lahav, 2010; Parga et al., 2018; Vitale et al., 2021). A concept that demonstrated a way to comfort the infant by capturing and replaying the maternal heartbeat is the Hugsy blanket (Claes et al., 2017).

During kangaroo care, the maternal heartbeat may be recorded, and when the infant is placed in the incubator, the blanket reproduces the heartbeat (Claes et al., 2017). Similarly, the Mimo pillow records a mother’s heartbeat and transmits it to the infant when distressed (Chen et al., 2015). Another product is the Babybe cradle (Natus Medical, USA), which features a gel mattress that simulates the mother’s breathing movements and a maternal wearable device that transmits the mother’s heartbeat and voice to the baby in real-time when they are separated (Vitale et al., 2021). Rocking provides vestibular stimulation that replicates the rhythm of maternal walking and fetal movement in utero (Korner, 1990; Zimmerman & Barlow, 2012).

Methods

Tripartite Methodology

Within this study, we focused on the process of understanding and incorporating the values of parents and clinicians as direct stakeholders. In this study, we used the definition of values as ‘what a person or group considers important in life,’ following the framework of Friedman et al. (2006), which distinguishes between moral values (such as autonomy, dignity, clinical safety, and justice) and stakeholder preferences (such as comfort, usability, and aesthetics). In the context of perinatal intensive care, this includes, for example, the moral value of parental bonding and the non-moral value of preferring a translucent incubator or a specific aesthetic design of the incubator. However, the distinction between (non-)moral values is not always clear-cut. A preference may be given the status of a moral value when it reflects a deeper ethical concern, such as a design feature that allows parents to see their infant and facilitate bonding, or one that prevents light and noise exposure to reduce the infant’s stress. In this study, we included both values and preferences that were discussed by the stakeholders.

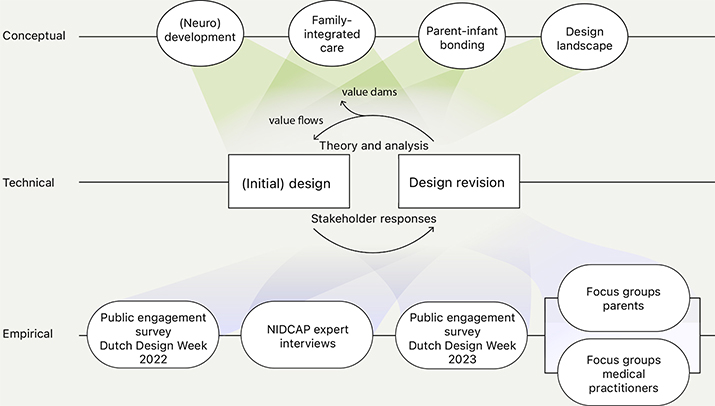

We invited parents of extremely premature infants, and a range of medical practitioners involved in current perinatal care, experts from the fields of neonatology, pediatrics, obstetrics, clinical psychology, as well as NIDCAP. Perspectives were also collected from the general public, who are considered indirect stakeholders. Information on study participant characteristics is presented in Table 1. Using a tripartite methodology (see Figure 1), we conducted (1) conceptual investigations, followed by (2) design investigations, and (3) empirical studies.

Figure 1. The tripartite process included conceptual, design, and empirical investigations.

Conceptual Investigations

Related literature was reviewed to identify and clarify the themes and values relevant to the design context, particularly current care aspects that may be altered by the technology being developed. Aspects identified included infant (neuro)development, parent-infant bonding, family-integrated care, and existing NICU design interventions. Pubmed and ACM databases were searched to identify relevant articles. Keywords used in different combinations were (neuro)development, fetal (neuro)development, parent-infant bonding, family-integrated care, family-centered care, NIDCAP, kangaroo care, NICU design, extracorporeal life support, artificial placenta, and artificial womb technology. A hand search of the reference lists of the most relevant literature was conducted. The literature study served to sensitize the researchers and thus prepare them for the interview questions, preliminary sketches, and prototypes.

Research-through-Design Investigations

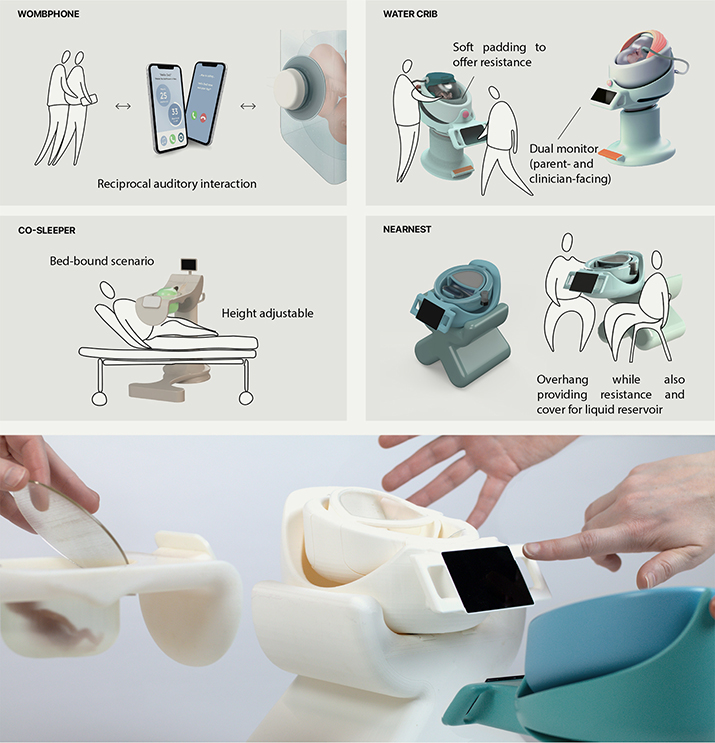

This research is conducted within the EU-funded Horizon 2020 Perinatal Life Support consortium. As part of this research, a technical proof-of-concept prototype of the incubator was developed by RWTH Aachen University to demonstrate functional feasibility (Heyer et al., 2024). In parallel with this technical development, we initiated a well-being-oriented design exploration focused on the emotional, ethical, and relational dimensions of incubator use in neonatal care. To support this exploration, a series of conceptual sketches and small-scale prototypes were created, which are the focus of the present study. Alongside value collection, design investigations into the APAW system’s features and mechanisms were conducted iteratively and in an integrated way. The design-for-debate prototypes in this study were designed to facilitate tangible demonstrations and discourse on concerns and opportunities relevant to the design of the APAW system. Although based on medical and technical requirements, the prototypes featured in this article are not medical devices and are not intended to demonstrate technical advances. The prototypes were modeled at a 1:4 scale and then 3D printed. The functionality and interaction of the prototype were explained verbally to the participants and visually through renders in a slideshow. Focus group participants were able to physically interact with the prototypes.

Empirical Investigations

To broaden the value collection before conducting in-depth conversations, we conducted a survey with 138 responses, featuring open-ended questions, to gather insights on concerns and opportunities from a broad audience during Dutch Design Week (Eindhoven, the Netherlands) in 2022 and 2023. Using a Showroom approach (Koskinen et al., 2011), we exhibited small-scale prototypes and research artifacts, aiming to assess audience perceptions on the technology (see Figure 2). Survey participants were selected by convenience sampling. Due to the nature of the exhibition, in-depth conversations were not possible, which may have affected engagement levels compared to other empirical studies. Although entry was free, the visitor profile, likely skewed towards those interested in design, may not accurately represent the broader population. The surveys used in both years were substantially the same: after viewing the exhibition, participants received a tablet to complete a short questionnaire with open-ended questions and text boxes for short-answer responses. The average time taken to complete the survey was 4.5 minutes. This survey included several inquiries: (1) What is your perspective on conventional incubators? (2) What do you appreciate about a potential new incubator, also known as an artificial womb? (3) What concerns do you have about such a future incubator? (4) What do you think is important in the design of such an incubator?

Figure 2. Perinatal Life Support research presented at Dutch Design Week 2022.

Seven semi-structured interviews were conducted with medical practitioners experienced in NICU care, particularly those with expertise in family-integrated care. Experts were selected through purposive sampling. The interviews lasted between 30 and 45 minutes and were audio-recorded. The questions focused on the current care of premature infants, exploring both positive and negative aspects. A comprehensive list of the questions is available in Appendix 1. Interviewed NIDCAP expert IDs are labeled “E” followed by their interview number (e.g., E1). Data collection was concluded after participant E7, as there was sufficient overlap in responses across participants E1–E7, with few new insights emerging after the initial interviews. This led to repetition and data saturation in the later interviews.

As part of a large qualitative study ‘Towards INdividualized care for the Youngest’ (TINY), focus group interviews with parents with experience of (threatened) extreme preterm birth (< 28 weeks of GA) (n = 15) and six focus groups with medical practitioners (n = 46) working in perinatal care (neonatologists, gynecologists, psychologists, and nurses) were conducted.. In these focus group interviews, counseling, decision-making, medical ethics, and design prerequisites were discussed, during which small-scale physical prototypes and concept sketches were presented, sparking discussions. While an in-depth thematic analysis of these studies is part of another article, this article discusses the use of prototypes within the tripartite methodology and highlights excerpts of the reactions they elicited. Questions related to the design can be found in Appendix 2. Prototypes differed in interaction possibilities, visibility of the infant, user scenarios, geometry, color, and material. To create an environment where all focus group participants could freely express their thoughts, data anonymization was included as part of the informed consent process.

Design Prototypes

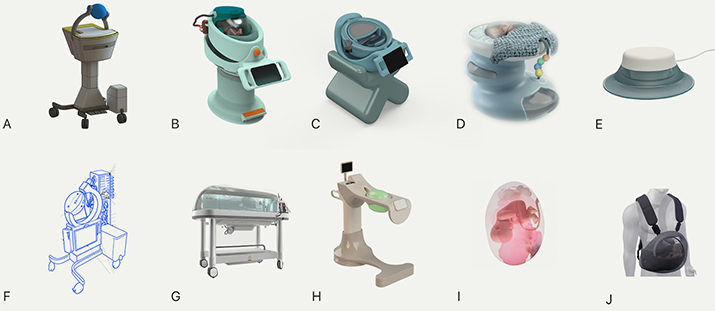

The design approach (see Figure 1) resulted in several design ideas, sketches, and small-scale physical design prototypes. To include in the surveys, interviews, and focus group interviews, several designs from our and external research groups were shown. The iterations of this study did not aim to arrive at a final design prototype but rather to explore a range of design concepts. The concepts synthesized different design priorities; the scenarios supported by the prototype aim to encourage debate on a clinically and technically plausible design direction preferred by stakeholders. The (non-functional) prototypes differed in concept, material, interaction possibilities, visibility of the infant, user scenarios, geometry, and color to elicit reactions. Refer to Figure 3 for an overview of the concepts included in the surveys and focus group interviews.

Figure 3. (A-J) Prototype illustrations that were included during surveys and focus group interviews.

- Designed as a full-system APAW design that could mimic maternal movements. (Design by van der Kruijs, W.).

- Designed as a full-system APAW design, mimics a rounded baby crib. It features a light-reducing cap, two axes for horizontal and vertical rotation, a monitor for both parental and clinician access, and customization accessories. The crib is designed for a single-room setting, creating a private, stress-reducing environment. (Design by Hoveling, T.).

- A full-system design. The reservoir is equipped with soft padding that may move and emit sounds resembling the maternal environment. It features height adjustability and extension capabilities for positioning over a hospital bed or for more comfortable parental seating. Parts of the crib surrounding the reservoir are detachable, facilitating parental touch (Design by Wijen, M. and Kuijpers, R.).

- A full-system design. The infant is placed in a liquid-filled bag on a soft surface. A cover, such as a blanket, is placed over the infant. (Design by Hoveling, T.).

- A separate functionality for liquid-based incubators. It may facilitate auditory bonding by allowing parents to call their infant. Through a mobile app, not only can recorded sounds be shared, but parents may also receive information. These sounds are transmitted to the infant via a speaker attached to the APAW system’s fluid reservoir. (Design by Monincx, M. and van Loon, R.).

- Designed as a full-system APAW design. (Design by Thielen, M.).

- A fluid-filled incubator with a conventional neonatal incubator typology.

- A full-system design that may promote parent-infant closeness by allowing parents, even when bedbound, to sit underneath the fluid reservoir and let it rest on their abdomen. It accommodates seating on either side of the infant, features a transparent reservoir for visibility, offers dual-axis rotation, and is height-adjustable. (Design by Verschueren, K.).

- A fluid-filled reservoir that mimics the uterus as an organ.

- A wearable system. (Design by Cybele, Edinburgh College of Art, UK (Iqbal, 2017))

Several concepts (B, C, E, and H) were turned into small-scale physical prototypes for the exhibits and focus group interviews (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Top: Concepts that were developed into physical prototypes. Bottom: Small-scale (1:4) physical prototypes during workshop setting. The contributors include Monincx, van Loon, Hoveling, Verschueren, Wijen, Kuijpers, van Haren, and Delbressine.

Data Analysis

Data from each empirical investigation (surveys, interviews, and focus group interviews) were analyzed separately, using conventional thematic content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) to identify themes, generate initial codes, and refine them. A process of open, axial, and selective coding was performed using ATLAS.ti 24.0.0 for Windows (Berlin, Germany), following Strauss and Corbin’s Grounded Theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1994). Quotes included in the results section were translated from Dutch to English. Quotes from the interviews with NIDCAP experts are accompanied by participant ID.

Value-sensitive design encourages finding solutions that maintain a balance between the values under tension, ensuring all values are eventually upheld in the technology. Therefore, we use a simplified “value dams and flows” method for value analysis to identify viable designs and features (Friedman & Hendry, 2019). Features facing opposition from all stakeholders are discarded (“value dams”), while preferred design elements are selected as promising solutions (“value flows”) and forwarded to the next design iteration. Features for which no consensus was found were regarded as value tensions and thereby constraints, or design trade-offs, of the design space (Friedman & Hendry, 2019). Miller et al. (2007) outline a method for quantifying addressed values, ranking them by percentage, and setting a threshold for value flows and dams. However, the anonymization of focus group interview data in our study made it impossible to trace individual contributions, preventing us from using this systematic approach. Instead, we identified value tensions through thematic analysis and mapped these tensions within and between stakeholder groups.

Table 1. Demographics and characteristics of participants.

| Phase II: Family-integrated care expert interviews (E1-E7) | |

| ID | Role |

| E1 | Senior NICU nurse |

| E2 | Neonatologist and pediatrician |

| E3 | Physician and researcher |

| E4 | Guides preterm infants and parents, trains healthcare professionals in NIDCAP |

| E5 | Clinical psychologist |

| E6 | General practitioner |

| E7 | Neonatology specialist nurse and case manager for extremely premature infants |

| Phase III: Parent focus group (FG-parent1-2) | |

| Participant characteristics | n = 15 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 10 |

| Male | 5 |

| Phase IV: Interdisciplinary professionals focus group (FG-medical1-6) | |

| Participant characteristics | n = 46 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 38 |

| Male | 8 |

| Discipline | |

| NICU nurse | 16 |

| Neonatologist | 12 |

| Nurse practitioner | 5 |

| Maternal fetal specialist | 4 |

| Midwife / physician assistant obstetrics | 4 |

| Obstetrics nurse | 3 |

| Other | 2 |

Results

Thematic Analysis of Empirical Studies

Several themes emerged from the public engagement survey, interviews with NIDCAP experts, and focus group interviews with parents and medical practitioners related to the design of APAW technologies: safety, nurturing environment, monitoring and intervention, family-integrated care, parent involvement, parent-infant bonding, and visceral design.

While the public engagement functioned as a societal exploration to broaden the spectrum of values, it set a foundation for further in-depth analysis through (focus group) interviews. Where the survey results focus on identifying values, the (focus group) interviews offer richer, more nuanced insights into the expressed perceptions. We refer to the participants as survey respondents, NIDCAP experts, parents, and medical practitioners.

Safety

In response to the inquiry about the most crucial design aspects during APAW technology development, numerous survey respondents underscored the importance of durability, reliability, medical access, and ease of use for healthcare professionals. The potential benefits for the physiological development of the infant in an environment mimicking the uterus, and the related potential for reduced infant discomfort, were appreciated by NIDCAP experts. Expert E2 described: “[..] it’s terrible for parents to see their child in pain or discomfort from IVs, lines, tubes, wires, and such [..], if the child can move freely but also have the security of a nest-like space.” Similarly, parents appreciated the potential reduced risk of infection and the avoidance of IV lines and resulting trauma as the benefits of APAW technology.

Medical practitioners raised concerns regarding the risk of cannula disconnection due to infant movement, how to maintain sterility, and how to ensure stability and secure fixation of the system, as well as concerns about the durability of the liquid-containing bag. Also, parents emphasized safety, stability, and reliability; “That there is a triple assurance that the artificial placenta doesn’t fail. Also, in terms of the sturdiness of the bag” (FG-parent1, 52:51). Certain prototype features intended to enhance interaction were viewed negatively by parents if they compromised on safety or reliability. For example, the ‘Co-sleeper’ prototype’s overhang (see Figure 3H & Figure 4) was seen as unstable, with concerns about the free-hanging bag potentially rupturing or being bumped into, undermining its overall positivity on parent-infant interaction. Generally, designs exposing the flexible liquid reservoir unshielded, such as Figures 3A, F, and H, were deemed too vulnerable.

Nurturing Environment

NIDCAP experts emphasized that the challenge of this technology lies in ensuring physiological security while also enhancing the overall quality of life. Emphasis was placed on the importance of focusing more on the emotional aspects during technology development, widening to psychopathology, psychosocial functioning, parent-infant bonding, and general quality of life outcomes. This was echoed by survey respondents who used ‘caring’ as a common descriptor for an ideal incubator.

Concerns were raised about whether current clinical knowledge can ensure proper immune and neurodevelopment, as well as hormone, growth factor, and nutrient supply, with this technology, questioning its ability to surpass existing care. Expert E2 described, “APAW wants to try to reduce mortality [..] and reduce those complications and thereby also improve the long-term outcomes. However, [..] is there also an eye for [..] the psychopathology, the psychosocial functioning, because that determines even more than your lung function, what your quality of life ultimately is.”

Parents emphasized reducing exposure for the infant to harmful stimuli. A parent explained, “If you have the option to eliminate as many [stressor] stimuli as possible in such an incubator, I would indeed opt for such a system” (FG-parent1, 1:07:06).

Physical prototypes with soft, expandable reservoirs and surroundings, which allowed infants to stretch and move, received positive feedback as they could provide intra-uterine-like pressure and comfort. A medical practitioner described, “although [in current care] we come up with various solutions [..], it doesn’t provide the resistance they would experience in the womb. This ‘Watercrib’ design offers that, [..] the ability to push against something, hopefully receiving the necessary stimuli” (FG-medical4, 14:39).

The design prototypes were generally assessed for their ability to shield the fetus from stressors, such as alarms, light exposure, and the transport of the incubator, as well as other harmful external influences. Design features that maintain womb-like lighting conditions, while allowing for medical observation, such as the adjustable covers in Figure 3D and in the prototype ‘Watercrib’ (Figures 3B & Figure 4), were regarded positively. In the survey and interviews, auditory stimulation, such as continuous ambient noises, the mother’s heartbeat, bowel sounds, and exposure to the human voice, was mentioned as desirable. Another aspect discussed was the possibility that the incubator environment mimics the mother’s movements. This potential was appreciated in the prototype figures (Figures 3A and F). Lastly, several medical practitioners and NIDCAP experts discussed the possibility of altering the taste and smell of artificial amniotic fluid.

Monitoring and Intervention

Survey respondents expressed concerns about the ability to accurately assess the infant’s condition and the system’s conditions, due to limited physical access and potentially reduced visibility. These concerns were further addressed in the focus groups with the medical practitioners. The electronic screen shown in Concepts Figure 3B and C prompted discussions on the potential for having different interfaces for users, parents, or clinicians. Several practitioners mentioned the wish that the child needs to be observable. In contrast, others raised the point that some parameters may be indirectly gathered and do not need to be visually observed, as is the case in current obstetric care. In the discussion on infant monitoring, medical practitioners debated whether to approach it from a gynecological or neonatal perspective, utilizing their respective technologies. The technology should improve infant outcomes; thus, APAW incubators must meet existing monitoring standards. However, the parameter values are neither exactly like those in the intra-uterine environment nor completely like those in the NICU or on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

A medical practitioner asked, “For many [premature infants] there’s an underlying issue [..] that prevents them from progressing further. Can you investigate this in those four weeks [when the child is in the APAW system]?” (FG-medical1, 07:35). Other medical practitioners stated that the conceptual idea of the APAW system also seems to entail that less care can be given. In an ideal situation, they argued, it needs as little maintenance or intervention as possible, “...let’s limit ourselves as much as possible, because we could do all sorts of things. We should leave [the infant] alone. Or [intervene] as little as possible, other than perhaps small movements [..] and [focus on] that which could be done outside the child: blood [sampling]” (FG-medical3, 1:15:54). Use cases for blood sampling were discussed, such as to help verify medication doses and conduct CRP tests. At birth, the child is exposed to external elements and will also receive extracorporeal blood circulation, necessitating infection monitoring. In terms of medical access, when reverting to conventional care in case of emergencies, quick access to the child is essential.

Parent-infant Bonding

Survey respondents, NIDCAP experts, and medical practitioners all expressed their concerns regarding parent-child separation. They emphasized the need to develop design opportunities for parent-infant interaction, such as physical closeness or some form of contact. They described the APAW incubator as bridging the gap between the natural conditions of the womb and traditional incubators. However, it lacks the immediate maternal closeness that is achievable in current incubators. Parents also confirmed this in the focus groups. They regarded the ability to connect with their child as crucial. Designs that seemed to hinder this possibility were evaluated negatively, “First [the child] is in your belly, there you can make contact, and with premature birth it can be through kangaroo care. But how do you ensure this if your baby is in such a new incubator?” (FG-parent2, 17:20). Experts mentioned a discrepancy between expectations of a newborn and the reality of a premature baby in an incubator, emphasizing the need for physical reunion to facilitate parental attachment. Expert E3 described, “In the case of a spontaneous birth, [..] you may not be able to see the child, you must rely on the equipment or the doctors [..] as a parent, you want to feel more closeness [to your child].”

Designs that facilitated greater physical closeness, such as features that allowed parents to touch, sit close by, or sit underneath the incubator, were regarded as positive. For example, the possibility of placing the incubator in a static kangaroo care position, such as in physical prototypes ‘Co-sleeper’ (see Figure 3H & Figure 4) and ‘Nearnest’ (see Figure 3C & Figure 4), so that the parents may sit or lay below, was welcomed by the majority of parents, medical practitioners and NIDCAP experts, “As if you can hold him a bit, at least for the feeling [..] then it’s really a great, kind of kangaroo care idea. Only in a very different way” (FG-parent2, 33:04). In line with NIDCAP expert E2: “If [parents] can’t hold the child, they want to see and touch the child.” This was reiterated by parents, who judged the ability to feel, touch, or hold the infant, such as its kicks, as important. This was confirmed by their preference for prototypes made of soft materials, which allowed them to ‘feel’ the child.

Survey respondents, NIDCAP experts, and medical practitioners all proposed solutions to overcome the physical separation. A wearable solution was often proposed. Expert E2 suggests, “We need to get the idea of the incubator out of our minds [..] if you could carry a warm bag filled with fluid, containing a baby, on your belly, or at least be able to sit or lie down with the baby close by, it would be much better than in a fishbowl.” Other stakeholder suggestions were a hybrid system that could be both wearable and stationary. A setup allowing parents to lie or sit closely near their child, or the ability to place and tilt the ‘bag’ on the parent’s lap, as in ‘Co-sleeper’ (see Figure 3H & Figure 4), ‘Nearnest’ (see Figure 3C & Figure 4), and using the arms of Figure 3A. However, parents viewed the physical moving or transportation of the incubator as undesirable. A wearable belt attached to a mother’s abdomen was proposed, capable of recording and transmitting signals (e.g., heartbeat, movements) to the incubator and vice versa, thus enabling the device to simulate, e.g., infant movements for the mother. There were disagreements in these discussions, some medical practitioners and survey respondents cautioned against overlooking the fact that it remains a highly risky intensive care treatment, noting, “[With such solutions] we focus more on treating the mother than the child” (FG-medical3, 01:13:28) and, “I find the difficult part in the discussion: we want to be as close as possible to the womb, while on the other hand, we want to improve it for the parents” (FG-medical3, 01:11:57).

Sound, as demonstrated by the ‘Womb Phone’ (see Figure 3E & Figure 4), was mentioned by all stakeholders as an important means of connecting with the infant, fostering two-way auditory interaction. Related to this sensory stimulation, experts and medical practitioners emphasized the significance of reciprocal natural (unrecorded), continuous feedback in the interaction between the infant and the exterior, such as the parent.

The visibility of the child emerged as a consistent priority. One parent described, “When it’s in the womb, you don’t have a choice, […] but once it’s brought into the world, I would really appreciate being able to see the child to establish a connection” (FG-parent2, 24:25). Parents described wanting to have the option to see the child live, but also through video. “If you want to go home, you can still watch through a [video] stream [..] it would also be nice if […] close family could follow along, you need them in the process” (FG-parent2, 25:40). Parents also mentioned that it is beneficial if moments can be captured, to revisit them later, for reflection. Survey respondents expressed a desire to see the infant and mentioned that transparency, partial transparency, translucency, or a video connection would be desirable.

Family-Integrated Care

The importance of considering the psychological and emotional well-being of both the infant and the parents was mentioned by survey respondents. Descriptions emphasized the need for psychological support, enhancing active maternal involvement, facilitating parents’ access to information and monitoring, and ensuring the technology is also humane for healthcare staff by addressing the emotional needs of both families and providers. Experts discussed the stress that parents face and how parents often struggle to comprehend events as they unfold. Expert E4: “As soon as the child arrives on the ward, parents often feel that the child belongs to the ward.” The parents also repeated the overwhelming experience. Allowing participation in care was frequently mentioned as important by all stakeholders, and possibilities, such as being able to sleep next to your child, as envisioned in the prototype ‘Co-sleeper’ (see Figure 3H & Figure 4), were discussed. A parent explained, “That [the incubator] itself is accessible. That as a parent you can do something with it, instead of sitting a meter away watching” (FG-parent1, 55:58). In a related context, medical practitioners noted that the impact of sharing detailed information (e.g., heart rate) or visuals of the infant with parents vary; it can be stressful for some yet comforting for others; “It [Womb Phone] may be reassuring for a mother” (FG-medical2, 1:37:37). Experts recommended allowing uninterrupted parental access to the child’s status.

All NIDCAP experts emphasized the critical importance of integrating the benefits of NIDCAP and family-integrated care into any potential future care facilitated by APAW. Expert E2 noted, “[…] any system that improves technical opportunities is a step forward. But […] you shouldn’t disregard the progress made in the last 10 to 20 years, basically the soft things that improve the well-being of the infants.” Some medical practitioners expected that family-centered care would likely be reduced with this technology, as it would form a barrier between the infant and the parent: “The medical staff would only look at the numbers on the monitor, and the parents are sitting next to it for the show.” (FG-medical6, 01:03:04).

NIDCAP experts emphasized the crucial role parents play in soothing restless or stressed infants through physical contact, providing unparalleled comfort and dedication. Expert E2 explained, “[..] offer the boundaries of the womb, [..] and then they calm down, [..] it gives parents a role.” In addition, experts noted that kangaroo care not only reduces stress in infants but also in their parents.

In current care, parents facing a threatened preterm delivery are prepared to some extent, which may include discussions with clinical staff, visiting the NICU ward, or access to various forms of information. On the topic of preparing parents for the use of an APAW incubator, NIDCAP experts emphasized the importance of familiarizing them not only with the process but also with the technology’s explicit features and appearance, as well as the child’s appearance within it. Expert E3: “That they have already seen how their baby will be placed in the artificial womb […] not to be caught off guard by it.”

Parents addressed the personalization of the incubator, such as the use of personal blankets or the ability to track progress, similar to a growth journal. A parent recalled, “Once the oxygen was turned off, they would also get [..] a nice picture and the date added, that they had reached this milestone. Something like that [..] must be guaranteed in this as well” (FG-parent1, 01:11:30). Another parent shared, “[..] put photos next to each other. We are a week further. He has grown a bit again. That also gives a better picture of what is happening” (FG-parent2, 26:38).

The NIDCAP experts and medical practitioners in the focus groups discussed that the design of the incubator or new technology cannot be addressed in isolation from its environment. NIDCAP experts mentioned downsides of current NICU wards: limited privacy, exposure to the distress of others, and the alarms. NIDCAP expert E5 describes, “That you not only experience the stress of your child but also that of other children.” Introducing family rooms can offer privacy, but NIDCAP experts and medical practitioners underscored the need for continuous positive stimuli for the infant, even when parents are absent, making the presence of family members essential. They argued to offer family-friendly settings, recovery support for mothers, and breast milk pumping options. If this is impossible, alternatives must be provided to avoid under-stimulation of infants in incubators.

Visceral Aspects

Visceral design aspects relate to the immediate emotional responses a design evokes. The consensus among the public, parents, and experts was that conventional neonatal incubators, although functional, felt cold, clinical, stressful, and unwelcoming. The NICU environment was perceived as intense, with unfamiliar machinery and alarming sounds. When describing the ideal future APAW incubator, survey respondents used descriptors as warm, nurturing, protective, safe, friendly, soft (also material-wise), and rounded (e.g., womb, belly, egg, cocoon). This was confirmed during the focus groups; designs with soft and curved features, like those in Figure 3B, were favored and described as ‘friendly.’ In contrast, designs with more technical and angular features, such as those in Figures 3A and 3F, were characterized as ‘technical’ and not generally favored. A few medical practitioners in the focus groups explicitly reported experiencing [negative] emotional reactions when viewing all four physical prototypes, which were less prominent when seeing illustrations of concepts. The prototypes forced the participants to visualize the technology; one medical practitioner mentioned, “Now that I start to visualize it, I feel that this technology is so unnatural, and it really pushes the boundaries.” (FG-medical6, 01:00:34).

To achieve a softer appearance, several stakeholders (respondents and medical practitioners) proposed to hide technical elements, such as tubing, to make it look and feel less like a machine. A medical practitioner said, “It should be welcoming. It must invite parents close to it” (FG-medical2, 01:23:49) and, “it doesn’t need to look high-tech just because it’s a high-tech treatment. In current NICU’s, we have rooms that are homely and warm, other people [than staff] are involved too” (FG-medical2, 01:24:48).

Summary of Integrated Stakeholder Needs

The conditions from various stakeholders largely aligned and reflected a similar vision, such as value flows. In general, the involved parents described the ideal APAW incubator as being safe, stable, and friendly-looking, providing a protective environment for the infant, shielded from harmful external stimuli, yet receptive to external stimuli from parents. The overall clinical judgment (from NIDCAP experts and medical practitioners) favors a design that integrates elements to enhance safety via monitoring and medical access, alongside promoting parent interaction for infant (neuro)development by simulating a uterine environment. On certain aspects, there were different opinions, value tensions, and also within stakeholder groups. One of these design tensions is balancing the infant’s need to feel womb-like comfort with the reality that, for parents, the child is born and physically separated from the mother. Another tension involves striking a balance between parental control and ensuring the safety and stability of the system. Lastly, several medical practitioners found it challenging. They had objections to providing advice on the design due to the current limited knowledge about the effects of the technology on perinatal development.

While the interviewed parents may lack a comprehensive understanding of the technology, we can still discern their values and concerns. Additionally, empirical studies have captured the varying priorities among stakeholders regarding their values and concerns. An overview of key insights collected from the literature study and empirical investigations is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview of collected values and preferences. The interviewed stakeholders also spoke on behalf of others (e.g., infant or parent). These values are included in the column of the stakeholder who made the statement.

| Infant needs | Parental values and preferences | Medical practitioner values and preferences | Current technological / clinical knowledge | |

| Safety | Protection against hazardous factors that may cause infection and/or trauma. Secure and stable (cannula and reservoir) fixation. | Other functionalities should not compromise on safety or reliability. | Durability, reliability, medical access, and ease of use (attention to minimize user errors). IC treatment standards. | APAW studies have investigated contamination removal (Usuda et al., 2020) and cannula fixation (Verrips et al., 2023). Decannulation events were avoided by restricting the range of motion of animals (Partridge et al., 2017). |

| Nurturing environment | Intrauterine conditions for optimal development (e.g., in terms of stimuli, self-regulation). | Reducing hazardous stimuli exposure for the infant. | Uterus as comparator, as in current care. Appropriate developmental conditions. Flexible material of a liquid environment and boundaries to allow for self-regulation, muscle development, contracture prevention, and growth. | APAW studies have investigated movement and temperature control. NICU studies on neuroprotection protocols (Altimier et al., 2015). |

| Monitoring and intervention | Minimal- or non-invasive monitoring. Quick access to the child in case of necessary intervention. | Option to receive information, track, and share growth progress. Ability to see the child both live and through video. | Monitoring comparable or superior to current obstetric and NICU care. Blood sampling required, minimize other interventions. Quick emergency access, sterile, and safe. (In)direct visual observation: live, video, or through intrauterine monitoring means. | Studies have investigated non-invasive monitoring (Amendola et al., 2023), monitoring via umbilical vessels (Partridge et al., 2017). Adjustment of physical visibility (e.g., a cover over a transparent bag) and camera placement in the system. |

| Parent-infant bonding | Maternal stimuli (audio, taste, smell, vestibular) for reciprocal bonding and fetal sensorial development. Prevention of under-stimulation. | Enabling closeness to the infant. Allowing for parent-infant interaction and nearness to the infant. Contributing to care, reciprocal bonding (e.g., through sound). | Reduce physical parent-infant separation. Improvements of current care should be taken to future care. | Current bonding practices, such as kangaroo care, are limited due to the fluid reservoir. Proximity to the infant is limited due to the fluid-filled chamber. |

| Family-integrated care | Stress reduction by balancing protection from hazardous stimuli and safe parental stimulation. Enabling secure attachment with parents. | Receiving professional support. Friendly, quiet, and private setting, allowing for, e.g., co-sleeping and breastmilk pumping. | Continuing family-integrated care practice and NIDCAP. Single-family rooms from which medical practitioners are able to receive adequate alerts/notices. Parents are regarded as vital members of the caregiving team with access to information about) their baby. | Stimuli may be filtered via the liquid barrier. Single-family rooms have economical and logistical constraints. |

| Visceral design | - | Friendly, stable, protective, non-technical, and designed to alleviate an otherwise stressful environment. | Nurturing and friendly design to invite parents, hidden technical aspects, yet easily accessible. | - |

Discussion

In this study, we have applied a value-sensitive design methodology to collect and integrate insights from different stakeholders regarding their perspectives on the design of APAW technology. The first section of our study details the current knowledge of the (neuro)development, parent-infant bonding, and the current design landscape for perinatal care. Subsequently, through empirical studies and prototypes, we iteratively explored how novel perinatal technologies might be designed to support stakeholder values and concerns (Manders-Huits, 2011).

Past APAW studies have looked at the technology through various lenses, including fetal physiology (van der Hout-van der Jagt et al., 2022), the needs of parents, the needs of clinicians (van Haren et al., 2023), and societal (Nabuurs et al., 2023) and ethical considerations (Verweij et al., 2021) (Krom et al., 2023). This research seeks to expand the focus, incorporating a wider range of concerns and prerequisites that consider the broader impact on stakeholders and infant development. This is critical as participants in this study raised concerns that the existing technological setups in preclinical studies have primarily prioritized, or communicated on, immediate vital life-support needs. Research indicates that an infant’s sensory development benefits from parent-infant interactions, which should provide stimuli of appropriate intensity, duration, and pattern. Although APAW developers may recognize the need to integrate these ‘experiential’ requirements, there is a lack of studies directly addressing these needs. More efforts are needed to communicate the benefits and reasoning behind design decisions, particularly when they constrain aspects that would have been possible in conventional NICU care. This is crucial for broad stakeholder acceptance; stakeholder concerns should be embedded from the start, rather than being added as afterthoughts.

The development of technology is influenced by values, which can either compromise or support certain values (van de Kaa et al., 2020). Instead of postponing the identification of stakeholders’ experiential needs until after technology implementation, we should adopt methods that enable immediate input on potential research and development directions. Certain tensions or concerns may necessitate seeking solutions through technological adjustments that accommodate or find a middle ground between conflicting values, or by making value trade-offs and thereby weighing some values above others (Taebi et al., 2014). This study was a first step in exploring how these values, both within and across stakeholder groups, can be safeguarded through design. Future research could continue using a more extensive “value dams and flows” approach (Friedman & Hendry, 2019). Tensions could then be further investigated by adapting and focusing the interview and focus group guides on conflicting values, and thereby presenting and questioning design options that resulted from value trade-offs. Within this study, we followed a route of exploration through surveys and in-depth discussion through (focus group) interviews. Future research should elaborate on applying a systematic value trade-off approach, translating and integrating it with technical and clinical criteria (e.g., safety, feasibility, and effectiveness), thereby creating a guideline for APAW developers. For example, the value of parent-infant bonding, identified as a moral concern by various stakeholders, can be translated into a user requirement for visual and emotional connection. This, in turn, informs the development of technical design features, such as the transparency of materials, the positioning of the incubator, and video/audio input systems that allow parents to see and speak to the infant, even within a closed environment. Choosing between these design features involves trade-offs with clinical and technical criteria such as safety, feasibility, and efficacy. Various methods exist to systematically address conflicting values, such as trading the loss of one value for gains in another (van de Poel, 2015) or more quantitative approaches that derive the weights based on the preferences of the interviewed stakeholders (van de Kaa et al., 2020).

As APAW technology is still an abstract concept, engaging stakeholders through tangible interaction can lead to a wider and deeper range of insights into how people relate to it. Therefore, the varied prototypes in this study were designed to allow for articulation of (implicit) values considered important by the participants. In discussions, participants frequently agreed but encountered differences when asked to elaborate on or make their ideas concrete. Using physical prototypes in this context serves as a form of ‘value sensitive design generation’, a way to elicit, clarify, and negotiate values through material engagement. Prototypes can make abstract ethical concerns more accessible and actionable, enabling stakeholders to reflect on trade-offs visible between different prototypes and imagine use scenarios. This iterative, design-led approach can enrich the value-sensitive design methodology by grounding conceptual and empirical investigations in embodied experiences.

The thematic analyses in this study showed several areas of concern and provided insights into how design can address them. Recurring themes included safety, nurturing physical environment of the incubator, monitoring and intervention, parent-infant bonding, family-integrated care, and the visceral design aspects. In terms of safety, parents and medical practitioners raised concerns about the durability, reliability, and stability of the technology, as well as the long-term outcomes of the potential treatment. The interviewed professionals emphasized the importance of designing APAW technology to significantly improve infant outcomes beyond cardiopulmonary development, such as neurodevelopment, which requires a balanced stimulus that the incubator could be designed to provide. In terms of features and functionalities, the material choices of the prototypes triggered debates on self-regulation and muscular development. In contrast, the geometry of the prototypes sparked debates on parent involvement and the stability of the system.

A recurring topic was the visibility of the infant within the incubator, which is either transparent and womb-like (Verweij et al., 2021) or transparent for visual examination. Design interventions discussed in the focus group interviews, such as integrating video or adjusting the transparency of the incubator, may address these visibility concerns. Other value tensions emerged regarding access to perinatal physiological parameters. Parents expressed anxiety over constant access to alarms or heartbeats and not understanding the purpose of certain monitors, alarms, and wires, a concern echoed in other studies on current care (Aagaard & Hall, 2008; Roller, 2005). Conversely, parents in the focus group interviews expressed a wish to monitor their infants’ growth progress, as it would have been possible in conventional care. A solution discussed was a dual interface solution, both clinical-facing and parent-facing, that could address this need. Monitoring technologies from both the obstetric and neonatology fields should be utilized, and this will also necessitate the development of non-invasive methods to overcome the liquid barrier. Parent involvement in the care of the infant was regarded as important by all interviewed stakeholders.

Regarding the visceral design aspects, renders or prototypes that were positively judged in interviews depicted the infant in a secure, protected area, allowing for a certain degree of parent-infant closeness. The survey results showed that visceral reactions to conventional neonatal incubators often included terms such as ‘distant’ and ‘impersonal’. In contrast, an ideal design for an APAW incubator was uniformly described as ‘nurturing’, ‘friendly’, ‘warm’, and ‘soft’.

Although situated in the context of future perinatal technologies, the collected insights into stakeholder values reinforce existing evidence in the field of extremely premature infant care: progress made in the NICU, beyond cardiopulmonary needs, should be safeguarded. This viewpoint is reflected in the design features that stakeholders valued, such as neuroprotection, parent-infant bonding, and parental involvement through family-integrated care.

Limitations

This exploratory study aimed to provoke dialogue and thereby differs from typical clinical studies. Although our method may not accurately capture the exact values, preferences, or thoughts of a target demographic, it does open up various perspectives and considerations. These can be brought into the technological development process to explore new designs (Gaver et al., 2004).

Variations in data collection approaches, including showroom methods for public engagement and field methods for parents and medical experts (Koskinen et al., 2011), likely contributed to the varied depth and breadth of collected perspectives among stakeholders. However, the distinctions between direct and indirect (general public) stakeholders warrant these methodological differences. Apart from the surveys, the inclusion of only Dutch participants might have introduced bias, as experiences were informed based on current NICU care in the Netherlands. Cultural differences may also make a diverse range of technological setups and features preferable. A limitation inherent to the patient population is that the interviewed stakeholders often spoke on behalf of others, with medical practitioners representing both infants and their parents, and parents speaking on behalf of their infants. This may have introduced bias into the findings.

The small-scale prototypes in this study were intended to facilitate debate, not to meet medical-grade design standards. Managing prototype fidelity is crucial during stakeholder engagement; varying levels of detail in prototypes and sketches can introduce preference bias. The difference in prototype format and refinement could have skewed results by directing participant focus to certain aspects (Deininger et al., 2019). Highly detailed prototypes may suggest that significant adjustments are not possible, while overly abstract ones may not effectively encourage discussion with participants who are unable to envision beyond familiar scenarios. Some focus group participants mentioned that discussing design prototypes came too early, pushing them to accept the technology’s progress before addressing fundamental concerns.

Conclusion

This study used value-sensitive design methods to collect stakeholder perspectives on the design of APAW technology. Using a tripartite approach, we identified core values and concerns from parents, patient advocates, medical professionals, and the public regarding this technology. Using illustrations and prototypes of design concepts during conversations with stakeholders allowed for the addressing of implicit user needs, such as experiential needs. We iteratively explored how novel perinatal technologies might be designed to support stakeholder values and concerns. Our analysis of the values highlighted the importance of an integrated approach that prioritizes reciprocal parent-infant bonding and the well-being of both infants and parents. By adopting this approach for future APAW development, it may encourage responsible innovation through the timely assessment and integration of expressed concerns.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for their time and valuable insights into this study. We thank the team of Care4Neo and Stille Levens for their support in recruiting participants for the NIDCAP interviews and the focus groups in the TINY study. We thank Maud Wijen, Wout van der Kruijs, Ries Kuijpers, Anouk van Luijk, Jasper Sterk, Chet Bangaru, and Mark Thielen for their contributions to the research and fabrication of prototypes. We sincerely thank Jeannette Schoumacher, Lucas Asselbergs, Marjan Thielen, and Marcel Sloots for facilitating multiple exhibits of the research prototypes at Dutch Design Week–Drivers of Change in Eindhoven, the Netherlands. This work was funded by the European Union via the Horizon 2020 Future Emerging Topics call (FET Open), grant EU863087, project PLS, and Clinical Fellows Programme 90719039 of co-author EJT Verweij.

References

- Aagaard, H., & Hall, E. O. C. (2008). Mothers’ experiences of having a preterm infant in the neonatal care unit: A meta-synthesis. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 23(3), e26-e36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2007.02.003