Exploring Everyday Experiences of a Multimorphic Textile-form Artifact

Alice Buso *, Holly McQuillan, Kaspar Jansen, Himanshu Verma, and Elvin Karana

Delft University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands

Multimorphic Textile-forms (MMTF) proposes a novel approach for creating seamless and sustainable textiles by simultaneously understanding both textile and form, which change over time across material, social, and ecological scales. MMTF capitalizes on textiles’ ability to be situated in multiple contexts, i.e., multi-situatedness, for enriched experiences and prolonged user-textile engagements. In this paper, we delve into this under-explored potential of textiles’ multiplicity by investigating the materials experience, particularly the performativity of an everyday MMTF artifact, AnimaTo. We designed AnimaTo to display morphing behavior when exposed to water over two sequential stages: shrinking and unfolding. Then, we deployed AnimaTo in a two-week longitudinal study, presenting it as an ordinary tea towel and encouraging users to interact as they wished, guided by its evolving shape, size, and texture. We collected in-depth accounts of materials experiences combining qualitative and quantitative methods. AnimaTo’s morphing behavior generated curiosity, suggesting creative uses beyond the kitchen context. However, deviations from AnimaTo’s initial state also caused frustration and interrupted use. We discuss the design implications of MMTF artifacts, emphasizing a critical balance between function, temporality, and materiality. This work advocates for embracing multiplicity in designing textile artifacts, generating value at use time, fostering sustained user-textile relationships, and ultimately contributing towards regenerative futures.

Keywords – Materials Experience, Multimorphic Textile-form, Multi-situatedness, Performativity.

Relevance to Design Practice – This paper offers designers insights into introducing textile artifacts that change over time to people and investigating their experiences. Moreover, it contributes methodological insights to design communities interested in exploring materials experiences, particularly at the performative level, in everyday settings and over an extended period.

Citation: Buso, A., McQuillan, H., Jansen, K., Verma, H., & Karana, E. (2025). Exploring everyday experiences of a multimorphic textile-form artifact. International Journal of Design, 19(3), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.57698/v19i3.01

Received August 9, 2024; Accepted October 27, 2025; Published December 31, 2025.

Copyright: © 2025 Buso, McQuillan, Jansen, Verma, & Karana. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-access and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: alice.buso@icloud.com

Alice Buso is a designer and design researcher. Her doctoral research at Delft University of Technology demonstrates the challenges and opportunities when designing textile-forms through the lenses of performativity and multi-situatedness. The thesis advocates for holistic and ecological approaches to designing interactions with textiles that embrace their unique temporal, unpredictable, and multi-situated qualities. Alice currently works as Product Manager at Foamlab, where she leads the identification of application domains and business development efforts to translate bio-nanocellulose foams from lab scale into viable products and market opportunities. Trained in industrial design engineering, with expertise spanning textiles, smart materials, and biomaterials, she aims to advance the adoption of next-generation materials and support the transition toward sustainable and circular futures.

Holly McQuillan is an assistant professor in Multimorphic Textile Systems at TU Delft, where her research explores the design and development of complex interconnected fiber-yarn-textile-form systems as a means for transforming how we design, manufacture, use, and recover textile-based forms. Co-founder of the Centre of Design Research for Regenerative Material Ecologies (DREAM), Holly’s research explores the material potential of textile systems to transform how textile products are designed and made, while also enabling enriched experiences that extend use-time. Oriented through a holistic lens, and builds on her experience developing and disseminating the field of zero waste fashion design, Holly’s work advocates for a new understanding of the relationship between designer and system, material, and form to conceptualize and prototype alternative futures.

Kaspar Jansen is a professor of Emerging Materials at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering. He studied Chemical Engineering at the University of Twente and received his PhD degree from TU Delft in 1993 for his research on injection molding. After postdoctoral work at the universities of Salerno and Twente, he returned to Delft in 2001 to work as an associate professor at the Mechanical Engineering faculty. He joined Delft’s faculty of Industrial Design Engineering in 2012 and was appointed as a full professor in 2015. His current research focuses on smart textiles, particularly the development of soft, textile-based sensors for sports and health applications.

Himanshu Verma is an assistant professor of Inclusive Human-AI Collaboration at the Delft University of Technology (Netherlands) and an Affiliated Researcher at the Institute of Mathematics and Computer Science (CWI, Amsterdam). His current research focuses on designing and evaluating inclusive, collaborative, and empathic mixed-initiative AI agents that can act as effective team members and enhance the performative and creative potential of humans and teams. His work spans the contexts of healthcare, education, and accessibility. He is co-leading the largest Dutch public-private partnership on co-designing inclusive and accessible AI and XR technologies with diverse disabled communities through the TACIT project. His research is supported by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and Horizon Europe programs.

Elvin Karana is a professor of Materials Innovation and Design at TU Delft. She investigates the intersections of design, biotechnology, and materials science. Elvin founded the Delft-Biodesign Lab, which advances biodesign research by developing frameworks, tools, and methodologies that deepen engagement with microbial systems and inform the design of biomaterials that integrate into everyday socio-material practices, aligning with the cycles and temporalities of ecological systems.

Introduction

Textiles are the ‘archetypal everyday material’ (Lee, 2020), the most ordinary materials permeating and shaping our routines and environments. Our collective understanding of textile artifacts regarding their expected texture, appearance, and functionality is deeply rooted in the interplay between textile production methods, functional requirements, and cultural meanings. Recently, a significant paradigm shift has been introduced with the concept of Multimorphic Textile-forms (MMTF) by McQuillan and Karana (2023). MMTF represents a novel approach for seamless and sustainable textiles, wherein both form and textile are designed simultaneously, considering their temporality across material, use, production, and ecological scales. This approach suggests that textiles can be designed for multiplicity, capitalizing on their inherent abilities to invite people to act, i.e., performativity (Giaccardi & Karana, 2015), and to be situated in various contexts and serve multiple purposes—a concept known as multi-situatedness (Karana et al., 2017)—and therefore building towards extended lifespans. However, to date, no study has explored the use of multi-situated textiles in everyday life. To bridge this gap, we will investigate how the ongoing changes of an everyday, MMTF during use influence its performative qualities and invite people to situate it in multiple contexts. Specifically, we ask: 1) What role does textile-forms morphing behavior play in the unfolding of novel interactions, creative uses, and the emergence of unexpected performances?; 2) How does the performativity of an everyday MMTF evolve during use?; and lastly 3) How can we map material temporality shifts to materials experience, with a focus on the performative qualities? To address these questions, we designed a MMTF artifact for performativity, called AnimaTo, which reacts to water in two stages: shrinking and unfolding. This study builds on our previous work (Buso et al., 2024), which documented the design and making of AnimaTo, including material choices, weaving experiments, and the tuning of temporal behavior. In this work, we conducted a longitudinal materials experience study of AnimaTo through a two-week field deployment in eight households. We analyzed quantitative data collected from the experiential characterization and a movement sensor embedded in the artifact. We analyzed qualitative data collected during the interview sessions through thematic analysis. By combining this knowledge, we discuss the implications for designers of MMTF organized around the themes of function, temporality, and materiality. Our paper offers two contributions to the design research community. First, it sheds light on how the performativity of a MMTF unfolds in everyday life (theoretical). Second, it demonstrates how we can study and evaluate the performativity and experience of MMTF in general through an extended temporal frame (methodological). Specifically we ask: how can we map the changes in textiles to everyday experiences? The next section discusses the existing literature and theoretical background that inform our longitudinal study.

Related Work

Multimorphic Textile-forms (MMTF)

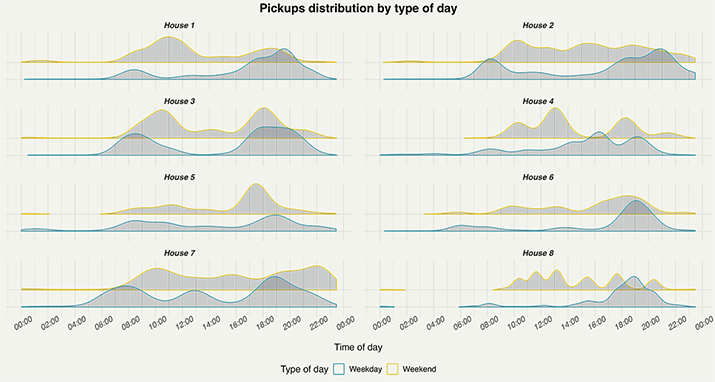

Diverse strategies to prolong textile artifact lifespans have been explored in design, e.g., textile artifacts with the possibility to renew or customize their expression (Fletcher, 2016; McQuillan et al., 2018; Persson, 2013; Riisberg & Grose, 2017), designing products with multiple states within product-service models (Earley & Forst, 2019; Niinimäki, 2013; Pedersen et al., 2019) and with the ability to change over time (Talman, 2022; Tonkinwise, 2004; Wu & Devendorf, 2020). Expanding on these lines of inquiry, McQuillan and Karana (2023) proposed MMTF as a design approach to invite designers to holistically consider the temporality of textiles throughout the interconnected scales of the textile system (Guo et al., 2016). At the material and design/production scale, textile-forms are textile-based artifacts obtained through the simultaneous thinking of both textile and form (Figure 1a). Textile-forms, obtained through diverse textile construction methods (i.e., weaving, knitting, 3D printing, molding, and growing), minimize textile waste compared to conventional textile production techniques and ease the seamless integration of responsive materials or technologies into textile artifacts. Zooming out at the design/production and use time, textile-forms can be designed to change over time, i.e., morphic textile-forms, through reversible or irreversible changes (Figure 1b). Zooming out even further at the ecological scale, morphic textile-forms can be designed to address broader sustainability concerns, i.e., MMTF (Figure 1c). MMTF are morphic textile-forms that can be developed through sustainable, circular, and regenerative practices, such as integrating ecologically safe materials, designing for circularity, zero waste, and multiple life cycles. This approach builds on design practices that increasingly aim to design systems that can adapt and co-evolve with human and non-human actors (Karana et al., 2023). Through MMTF thinking, we can envision textile artifacts with multiple functions or contexts of use, evolving seamlessly over time across their various embedded states and extending their lifespan beyond momentary experiences. However, this proposed multiplicity in use time to promote prolonged relationships with textile artifacts remains under-explored.

Figure 1. Multimorphic Textile-form (MMTF) thinking (McQuillan & Karana, 2023). Image: courtesy of the authors.

Performativity in Material-driven Design and Textiles

Understanding Materials Experience

The value of understanding the relationships between people and interactive artifacts through a material lens has been widely acknowledged by accounts in design and HCI, e.g., Jung and Stolterman (2011) and Wiberg (2018). Among these, the Materials Experience Framework proposed by Giaccardi and Karana (2015) considers materials as building blocks of experiences and as active collaborators in shaping people’s ways of doing and practices. The framework identifies four levels on which materials experience unfolds: sensorial (how does a material feel), affective (which emotions does the material elicit), interpretive (which meanings does the material evoke), and performative (which actions does the material elicit). In particular, the performative level of materials experience concerns which actions and performances a material elicits. During the use of a material artifact, when performances are repeated over time, they can either mutate existing practices or create new ones. Giaccardi and Karana’s (2015) understanding of practices as a sum of performances originates from social practice theories (e.g., Bourdieu, 1990; De Certeau & Rendall, 1984; Schatzki, 1996) and practice-oriented design (Kuijer & Giaccardi, 2018; Kuijer et al., 2013; Shove et al., 2007) that defined social practices as socially shared, materially embedded ideas of appropriate forms of action. For example, a social practice like cooking consists of a sum of performances, such as washing the vegetables and chopping ingredients. These are routinized activities that people perform as a result of the interplay between the objects and tools available, their competencies to use such objects, and their shared interpretations and ideas about the performed action (Shove et al., 2012).

To support designers’ understanding of the material at hand and reveal its potential for performativity, Karana et al. (2015) proposed the Material-Driven Design (MDD) method. Among the tools advanced by the MDD method, the Ma2E4 toolkit (Camere & Karana, 2018) guides designers to systematically investigate how material qualities elicit experiences on the four levels of Materials Experience, i.e., experiential material characterization. Understanding the experiential qualities of materials is essential in predicting how people might interact with and the timespan during which they engage with artifacts made from these materials (Karana et al., 2017). In particular, as performativity also affects other levels of the materials experience, it becomes relevant to map new performances and practices to the different levels, such as emotions, meanings, and associations (Karana, 2010) that arise during use.

Experience of Textiles

Because of textiles’ ubiquity and pervasiveness in our everyday lives, we are used to textiles that slowly change over time through repeated uses, accumulating imperfections (Rognoli & Karana, 2014) and material traces (Giaccardi et al., 2014). Especially, close-to-body textiles and garments manifest signs of body-textile relationships that carry embodied memories or records of events, becoming a kind of ‘historical artifact’ (De Koninck & Devendorf, 2022). Understanding the experiential qualities of textiles is essential for anticipating how people might interact with textile artifacts, particularly over an extended timespan of engagement (Karana et al., 2017). In the materials and design domain, the experiential material characterization of textiles commonly takes place in the form of empirical studies conducted in laboratory environments, which involve subjective user assessments of a pool of fabric samples, such as tactile or multi-sensory evaluations (Veelaert et al., 2020). Such studies range from investigating the tactile properties of automotive fabrics (Giboreau et al., 2001) to the experience of fabric shading (Karmann et al., 2023), the perception of naturalness in textiles (Overvliet et al., 2016), the affective tactile experience of textiles (Petreca et al., 2015; Stylios & Chen, 2016), and their impact on individuals’ wellbeing (Kyriacou et al., 2023). Recently, Parisi et al. (2024) presented a toolkit to support the design of serene textile experiences, providing a vocabulary to relate matter, form, and temporality in textile experiences. Other scholars have investigated the role of use in textile design processes, conducting empirical studies on the emotional value of textiles (Bang, 2011) and exploring how discontinuity and irritation can prompt users to actively redefine their relationships with textile artifacts (Bredies, 2008). However, as Veelaert et al. (2020) pointed out, longitudinal studies are necessary to investigate the unfolding of the textile experience over time. In the field of HCI, studies have extensively assessed the performance of interactive textiles (e.g., Luo et al., 2021; Nowak et al., 2022) and the interaction with textile interfaces (e.g., Karrer et al., 2011; Vogl et al., 2017). Others have investigated the impact of textile interfaces on user emotions (Jiang et al., 2020) and on their performativity (Buso et al., 2023).

A few studies have explored the experience of interactive textiles by conducting short-term and in-situ studies on specific technologies, such as knitted touch sensors (McDonald et al., 2022) and a touch-sensitive, lighted cord (Olwal et al., 2018). While these studies aim to address potential future use scenarios, they often occur in laboratory environments, failing to account for how the experience may evolve over time. Other design researchers explored textile experiences ‘in the wild.’ Mackey et al. (2017) conducted an autoethnographic study exploring the lived experience of wearing dynamic clothing for ten months. Valle-Noronha (2019), following the Research-through-Design (RtD) methodology (Stappers & Giaccardi, 2017), deployed color- and form-changing garments to explore how surprise and open-endedness can build richer engagements with clothes in everyday life. These studies provided valuable methodological contributions to exploring the experience of interactive textiles in day-to-day settings. However, none of the existing studies have systematically explored how the material and form qualities of textiles, which change over time, are experienced at the four levels of materials experience in everyday life, and how these changes elicit specific and creative actions from their users over time.

Performativity of Textiles in Everyday Life

The concept of the performativity of materials (Giaccardi & Karana, 2015) encompasses theoretical perspectives from post-humanism (Forlano, 2017; Wakkary, 2021) and new materialism (Barad, 2003; Bennett, 2010; Bennett et al., 2010) on the agentic capacity of matter in human-non-human relationships. Accordingly, designing for performativity involves the intention to create materials that support creative user-textile artifact interactions, potentially generating new, non-canonical, or non-conventional uses, thereby expanding the pre-established action repertoires and routines we already perform in our everyday, socially and materially situated activities. To understand how such expansions occur, Glăveanu (2012) offered a sociocultural understanding of affordance theories, arguing that people’s possibilities of action are restrained by an environment’s affordance (what one could do), intentionality (what one would do), and normativity (what one should do). The Romanian Easter egg decoration case study illustrates how creative practices emerge through diverse ‘mechanisms’, such as casual discovery, inventing new techniques and tools, and transgressing socially accepted norms. These mechanisms are closely tied to prior experiences, through which we make sense of the world and develop expectations about how an artifact might perform or how it may respond to user actions (Demir et al., 2009). When such expectations are not met, the resulting negative experience can be understood through Latour’s (1993) concept of distributed agency: skills and responsibilities are shared between humans and non-humans, and when a tool ceases to function, this balance shifts and the human part bears the burden. This is also reflected from a psychological standpoint. Norman (2013) observed that people often question their own abilities to handle non-functioning artifacts before attributing failure to the artifact itself.

Building on these perspectives, Barati et al. (2018) proposed the ‘disruption of function’ as a design strategy that intentionally interrupts expected affordances in a material to generate unexploited action possibilities. Grounded in practice theory (Schatzki, 1996), the conceptualization of ‘resourcefulness’ as a ‘dispersed practice’ (Kuijer et al., 2017) provides a valuable entry point to consider the materials’ performative qualities and their crucial roles in shaping our everyday practices with artifacts. Together, these approaches frame performativity as a means of supporting appropriation. Expanding on these discourses, this work also acknowledges the extensive work in everyday design (Wakkary & Maestri, 2007) that investigates the resourceful appropriation of everyday artifacts, e.g., through unselfconscious interaction (Wakkary et al., 2016), unintended product design (Wakkary et al., 2015), and the creative re-use emerging from product affordances (Soyoung et al., 2021). Here, ambiguity (Boon et al., 2018; Gaver et al., 2003; Sengers & Gaver, 2006) and failure (Petroski, 2018) in objects are shown as resources or strategies to invite action, adaptation, and improvisation.

In the field of textile experiences, Petreca et al. (2019) highlighted that even before the advent of responsive materials, “textiles were already performing and relating in such a manner. …Textiles are soft materials that respond actively to being touched or otherwise moved, and are generally worn close to our body, adapting to it” (p. 9). As textiles are inherently performative materials and are so deeply rooted in the fabric of everyday life, the actions we perform with them often go unnoticed. Therefore, understanding textiles through a performativity lens allows one to embrace their “becoming-ness” (Bergström et al., 2010) and their ability to be “alive, active and adaptive” (Karana et al., 2019) to invite creative interactions. The performativity of textiles has been explored in design research and practice across different disciplines, ranging from textile design (e.g., Jacqueline Lefferts: http://www.jacquelinelefferts.com/pleasebeseated; Salmon, 2020) to fashion design (e.g., Lamontagne, 2017), from interactive and performing arts (e.g., Skach et al., 2018; Dopple: https://www.nerding.at/dopple/) to architecture (e.g., Schneiderman & Coggan, 2019; Thomsen & Pišteková, 2019). Recently, accounts in HCI textiles investigated the actions elicited by textiles for input-output pairings in textile interfaces (Karrer et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2010; Olwal et al., 2018; Vogl et al., 2017) towards intuitive textile interactions driven by ‘textileness’ (Buso et al., 2022; Gowrishankar et al., 2017). Buso et al. (2023) designed woven textile-form interfaces for performativity as a first attempt to leverage the multiple states of woven textile-forms for richer interactions. However, it remains unclear how textiles with morphing behavior may invite new interactions in the mundane or ‘ordinary’ context of everyday practices.

Longitudinal Studies to Understand Everyday Experiences of Interactive Artifacts

To plan the longitudinal study with our multimorphic textile artifact, we looked outside of the textile field to address the need for more extensive examples of longitudinal studies with textiles in everyday life. Recently, a vast body of work in design and HCI has shifted focus from testing the ‘efficient use’ of interactive artifacts or early interactions to examining how artifacts are experienced over time and acquire meaning in one’s life (Karapanos et al., 2009). Empirical studies informed by post-phenomenological theory, specifically the technological mediation approach lens (e.g., Verbeek, 2005), inspired our documentation of the experience with our MMTF artifact. Here, interactive artifacts are deployed in a RtD fashion (Stappers & Giaccardi, 2017) to investigate complex human-artifact relationships in everyday settings (Odom, 2021; Wakkary et al., 2018; Zhong et al., 2021, 2023). A particular influence was Zhou et al.’s (2024) longitudinal study on the role of materiality and performative qualities in supporting human-living artifact engagements.

Because of the multifaceted nature of textiles’ performativity, both qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques (e.g., Baskan & Goncu-Berk, 2022; Karahanoğlu & Ludden, 2021; Vaizman et al., 2018) were necessary. The experiential characterization toolkit (Camere & Karana, 2018) collects data on the performative level in an observational manner. During the field study, however, we would not be able to observe the actions performed with the deployed artifact in first person, so we aimed to capture its use in a systematic and quantifiable manner while guaranteeing participants’ privacy. Recent HCI scholarship has highlighted the need to address privacy and data transparency in domestic IoT and sensing contexts (e.g., De Chaves & Benitti, 2025; Naeini et al., 2017), which informed our decision to capture only artifact-level interaction data, explicitly excluding any information pertaining to individual users. We were inspired by Zhang and Hung’s (2018) sensing system used to monitor continuous usage routines of objects to capture people’s resourcefulness in field studies. Here, we borrowed Verma et al.’s (2017) pervasive sensing technique through Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) beacons and wireless data loggers. To conclude, this work, through the field study of AnimaTo, aims to expand former user studies on living with interactive artifacts and serves as a first attempt to systematically investigate the materials experience of a MMTF artifact over time.

Field Study with a Multimorphic Textile-form Artifact

Methodology

The study presented in this paper consists of a field deployment of a research artifact (Odom et al., 2016; Stappers & Giaccardi, 2017) called AnimaTo in eight households in the Netherlands for about two weeks. Firstly, we wanted to keep track of the variation in the experience of AnimaTo at the different stages of the artifact’s lifetime. The responsible researcher (first author) performed three visits to the two adults living in each house at the start, halfway, and end of the study. Each visit consisted of a semi-structured interview with both participants together and an experiential material characterization (Camere & Karana, 2018) of AnimaTo with each participant individually. Secondly, we also aimed to collect rich accounts from participants about their interactions with AnimaTo through self-reporting. The responsible researcher received the participants’ self-reported pictures of AnimaTo every two or three days via WhatsApp. Lastly, we aimed to validate and triangulate participants’ felt experiences with quantitative data on interactions with AnimaTo. During the entire duration of the study, we collected frequency of use data through a BLE beacon in each AnimaTo and a data logger installed in the participants’ kitchens. This allowed us to record the frequency and duration of AnimaTo’s use throughout the day in a fine-grained manner, without the need for manual observations. Through the field deployment, we expected to observe changes in the materials experience and performativity of AnimaTo.

Design Rationale

AnimaTo is a MMTF artifact designed with the intention to alter its performative qualities in use and to be situated in multiple everyday contexts elicited by those alterations. We designed AnimaTo as a tea towel as we wanted the artifact to be a familiar everyday object that is intrinsically open to diverse interactions, serves multiple functions, and is movable to various situations to support diverse practices (Karana et al., 2017). Because the morphing behavior in a tea towel is novel, we sought to make AnimaTo look as much as possible like a regular tea towel, ensuring the right balance between familiarity and novelty and allowing it to fade into the background of everyday life (Odom, 2021). The first author conducted a short pilot study in her own household. This helped define the action repertoire for a tea towel and refine the temporal transition between AnimaTo’s initial and morphing states for the final design.

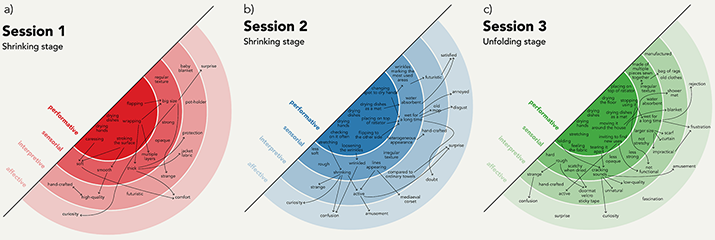

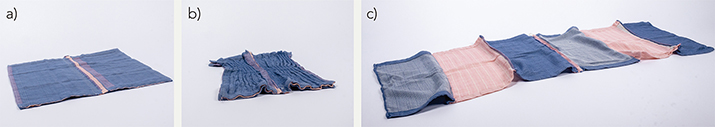

We selected water as input for AnimaTo’s morphing behavior, as this stimulus is commonly encountered in kitchens. We wove polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) water-soluble yarn in a multilayer woven textile-form to enable fiber-yarn (and ultimately form) morphing behavior when exposed to humidity and water. To sustain long-term morphing behavior, we intentionally tuned the temporal expressions of AnimaTo (Vallgårda et al., 2015) to evolve and remain interesting during the two weeks. AnimaTo’s morphing behavior consists of 2 stages (Figure 2). In the shrinking stage, during the first week, AnimaTo (originally 50 × 70 cm) gradually shrinks in length, revealing surface patterns. In the unfolding stage, after washing, AnimaTo expands into an artifact three times longer than its original size (approximately 50 × 200 cm) thanks to the dissolving of the PVA yarn.

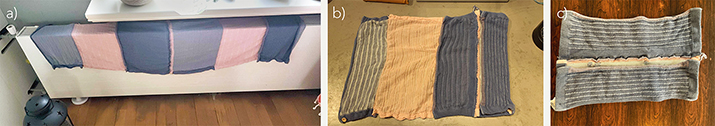

Figure 2. AnimaTo’s multiple states. (a) Initial state, presented to users as a tea towel. (b) After exposure to water, AnimaTo enters its shrinking state. (c) After washing, AnimaTo unfolds into an open-ended artifact.

The combination of material-form qualities and their temporal expression in AnimaTo aimed to be ambiguous and open to subjective interpretation (Tholander & Johansson, 2010). In the shrinking stage, we anticipated that participants might feel surprised and curious, resulting in frequent interactions with AnimaTo. In the unfolding stage, we speculated that the unfolding of AnimaTo would cause it not to be perceived as a tea towel anymore, and that participants may find alternative uses. Ultimately, we produced eight AnimaTo artifacts by industrial weaving. For more details, refer to Buso et al. (2024), which fully unpacks the design process of AnimaTo, including material choices, weaving experiments, and the rationale behind tuning its temporal behavior. Next, we will describe the research setup.

Recruitment and Participants

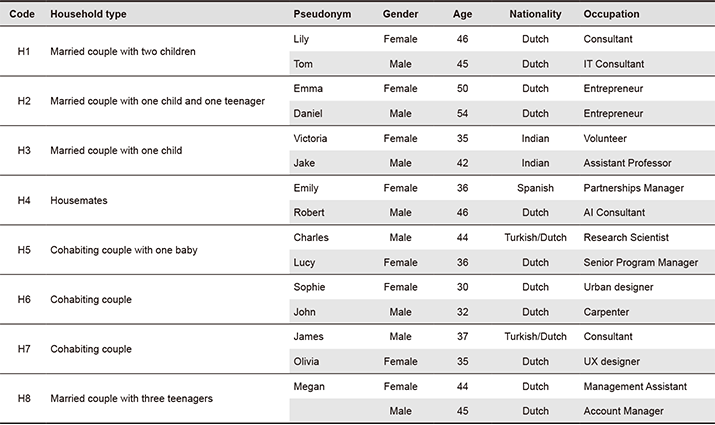

We recruited eight households as participants in the study. Our selection criteria included 1) that they lived within a 35 km radius of the research institute and 2) that they used the kitchen or prepared a meal at home at least once daily. We sent invitation flyers (see Appendix A) to 15 people in the neighborhood of colleagues unknown to the responsible researcher. Eight subjects agreed to participate in the study with their partner or housemate voluntarily, and none dropped out of the study. We recruited 16 participants living in eight houses (Table 1). All participants’ names are pseudonymized. The household types varied from married couples with children and/or teenagers to cohabiting couples and a couple of housemates. Participants have Dutch, Indian, Spanish, and Turkish nationality. Even though we sought a diverse sample of households, most participants (13 out of 16) have Dutch nationality. All study sessions were conducted in English, which was a second language for 13 out of 16 participants. When needed, the researcher provided clarifications in Dutch to ensure comprehension. Two participants had prior experience in design research studies.

Table 1. Overview of participants (8 females, 8 males, the average age is 41 years old).

The Study

Data Collection

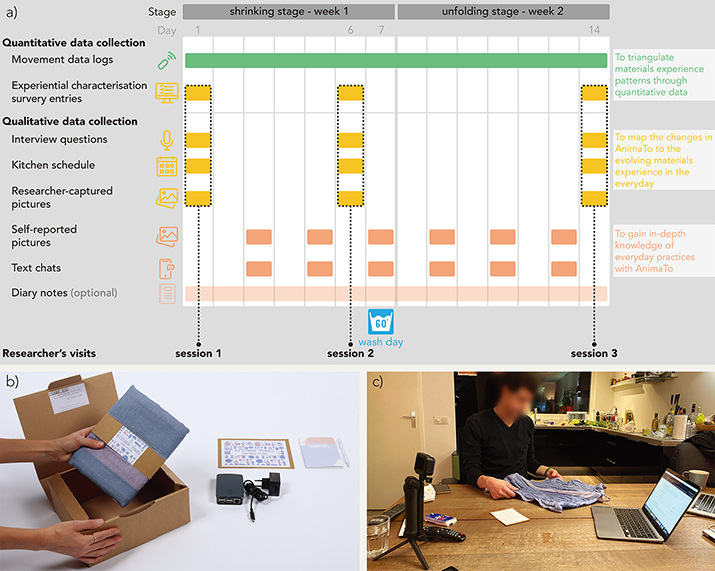

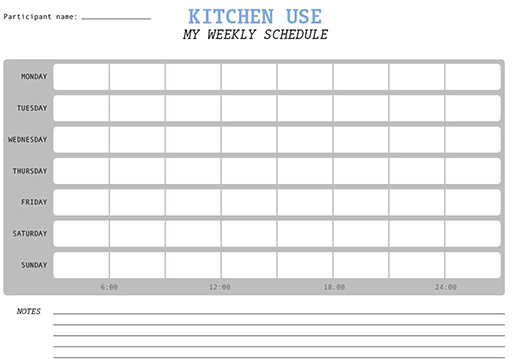

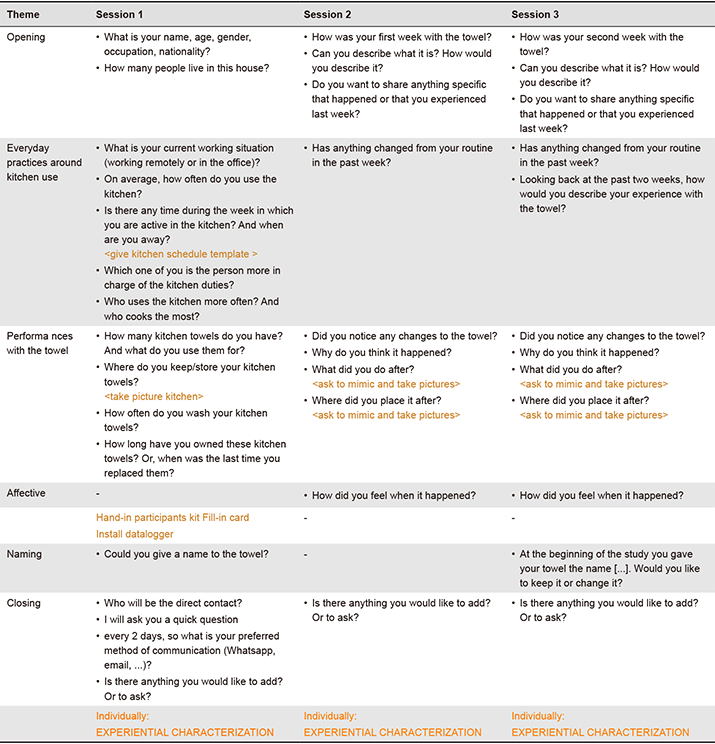

The data collection took place over two weeks between November and December 2023, with an average duration of 14 days (minimum 13 days, maximum 17 days) (Figure 3a). During the first visit, the responsible researcher delivered the participants’ kit (Figure 3b), including 1) the artifact AnimaTo with a BLE beacon, 2) an A5 instruction card (see Appendix B), 3) a notebook and pen, and 4) a data logger and its charger. The participants were asked to sign the informed consent form. The instruction card was read aloud to introduce the artifact and explain the study’s timeline. The participants were asked to replace their kitchen towel with AnimaTo and keep using it for the next two weeks. The participants were reminded that the artifact might change over time, but were not provided with specific details on the nature of the change. They were asked to continue using the artifact until the end of the study, and they were reminded that they could not do anything wrong. After the interview questions, the responsible researcher conducted the experiential material characterization, collecting answers on their laptop (Figure 3c). The participants were asked to wash the artifact only after the second visit, which took place around the seventh day of the study. At the beginning of the interview, participants filled out the kitchen schedule template (see Appendix C) to illustrate their typical kitchen use over an average week.

Figure 3. Data collection. (a) The study design and timeline. (b) Participants’ kit. (c) Interview setup.

Before leaving the participant’s house, the responsible researcher informed the participants and connected the data logger to the power supply in a safe spot in the kitchen. The second visit, which occurred at the end of the first week before the washing day, and the third visit, that occurred at the end of the study, consisted of some initial interview questions followed by experiential characterization. Each visit lasted between 45 and 60 minutes. This study protocol was approved by the research institute’s Human Research Ethics Committee. The interviews were both audio- and video-recorded. Due to the unavailability of some participants, three interviews were conducted via video call on Microsoft Teams and screen recorded. In total, we collected about 10 hours and 43 minutes of conversations, which were transcribed, 47 experiential characterization survey entries (1 missing because the participant was sick during a session), 45 self-reported pictures, 24 researcher-captured pictures, eight text chats, eight kitchen schedules, eight movement data logs, and diary notes from 1 notebook.

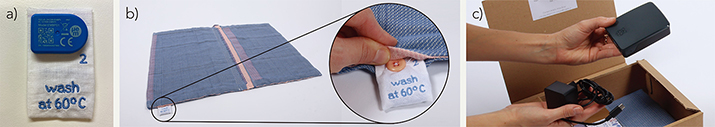

The Movement Sensing System

Inspired by the work of Verma et al. (2017), we developed a sensing system to detect the movement of AnimaTo, consisting of a BLE beacon and a data logger (Figure 4). For each AnimaTo, we fabricated a removable care label containing a BLE beacon with an accelerometer (EMBP01 from EM Microelectronic, Switzerland). Each beacon broadcasted a packet containing its Universally Unique Identifier and timestamp when the embedded accelerometers detected a movement for at least 2.5 seconds consecutively. To preserve battery life, the beacon returned to ‘inactive’ mode after more than 0.5s without movement. The data logger (Raspberry Pi 4B) received the beacon packets in proximity and locally stored them on a 16GB SSD card, while ignoring other nearby Bluetooth devices. Additionally, the beacon broadcasted an ‘inactive’ packet every hour during inactivity to check that it was working. Even though the selected beacons are fully waterproof, we recommended the participants to temporarily remove the label during washing to avoid battery damage due to high temperatures.

Figure 4. Movement sensing system. (a) A BLE beacon before being inserted into the care label. (b) The care label attached to AnimaTo via a button. (c) The data logger installed in every house.

Semi-Structured Interviews

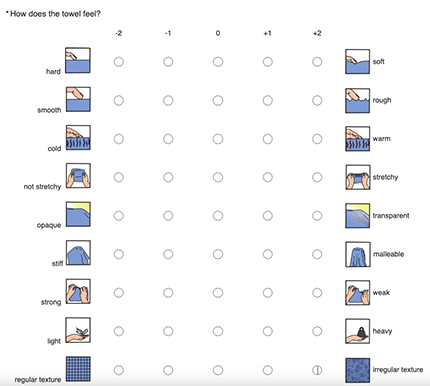

The semi-structured interviews were divided into two parts. In the first part, the participants were asked to answer questions together. In the second part, participants were asked to complete the experiential material characterization survey individually—the interview questions aimed to document the everyday practices with the artifact and its materials experience. The interview questions are based on the Materials Experience Framework (Giaccardi & Karana, 2015) and are designed to unpack the theme of performativity of AnimaTo (see Appendix D). The original experiential characterization toolkit (Camere & Karana, 2018) was adapted to better fit with textiles’ unique properties and digitalized on an online survey platform (https://www.qualtrics.com/) (see Appendix E for detailed information on the adaptations). At the beginning and end of the study, participants were asked to name the artifact to investigate whether participants related to it as a more-than-functional artifact, and how this might influence their materials experience.

Analysis

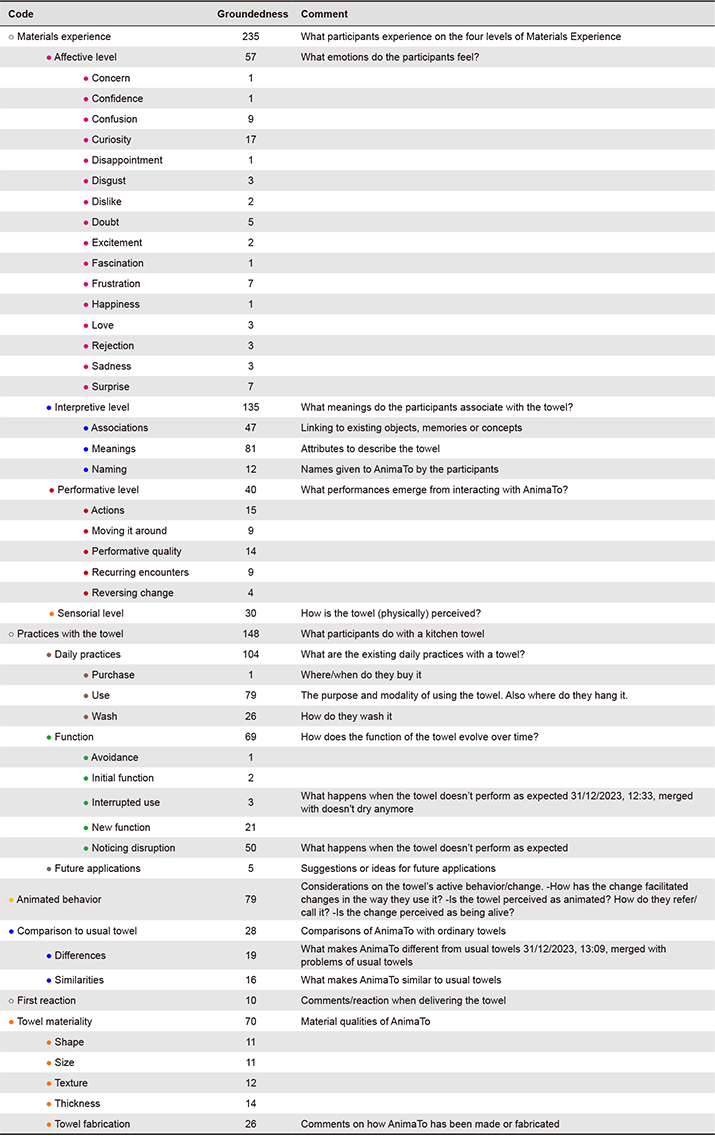

Thematic Analysis

After every visit, the video recordings were transcribed using an online transcription software (https://www.transkriptor.com) and manually corrected. The diary notes were manually transcribed. The interview transcripts, text messages, diary notes, and self-reported and researcher-captured pictures were imported into ATLAS.ti software (https://atlasti.com/). We conducted a thematic analysis over three phases, applying a hybrid coding approach (Clarke & Braun, 2013). In the first phase, the responsible researcher read through the entire dataset to familiarize themselves with the data and take notes. Then, we applied a set of a priori codes based on the four levels of materials experience (deductive coding). The researcher also started applying new codes that emerged from the existing ones (inductive coding). In the second phase, the responsible researcher discussed the newly emerged codes with the second and last authors, and together, they identified new potential codes for the second round of analysis and early-emerging themes. In the third and last phase, the responsible researcher performed another coding iteration and discussed the emerging themes among the research team using affinity maps. This phase resulted in the reframing of specific themes. Ultimately, this process yielded 50 codes and three themes in total. An overview of the codes and their corresponding descriptions can be found in Appendix F.

Experiential Characterization Analysis

We conducted a structured analysis of the survey entries from the experiential characterization survey. We considered each house as our unit of observation, based on the assumption that participants in the same house mutually influence one another. We computed summary statistics and frequency counts using R software and visualized the results. For the performative level, we combined the qualitative observation technique with quantitative analysis of the movement data collected from the data loggers. We took into account 1) the most common and unique actions performed during the sessions and 2) self-reported pictures, retrospective descriptions of actions during daily use, and actions re-enacted by the participants during the sessions. Moreover, we summarized the main experience patterns using the materials experience map diagram, as employed in Camere and Karana (2018) and Elkhuizen et al. (2024) (see Appendix G).

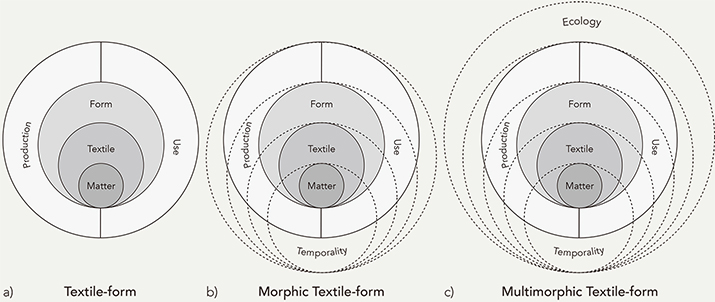

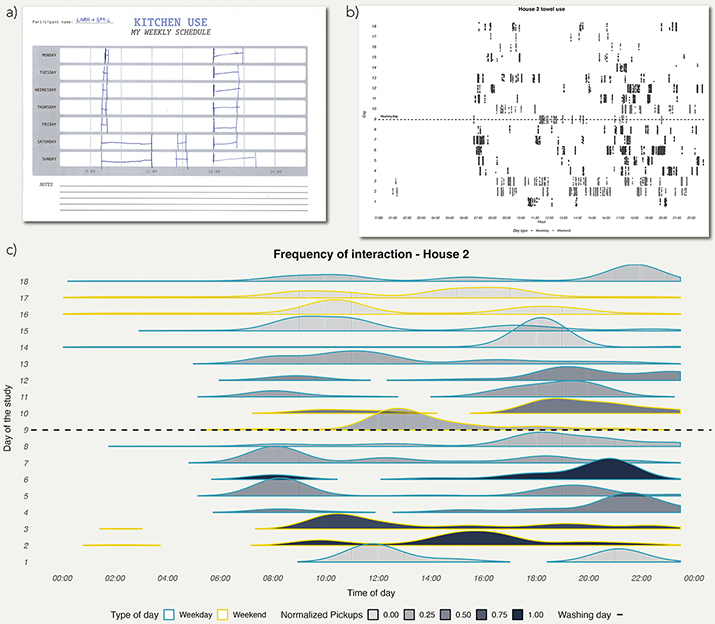

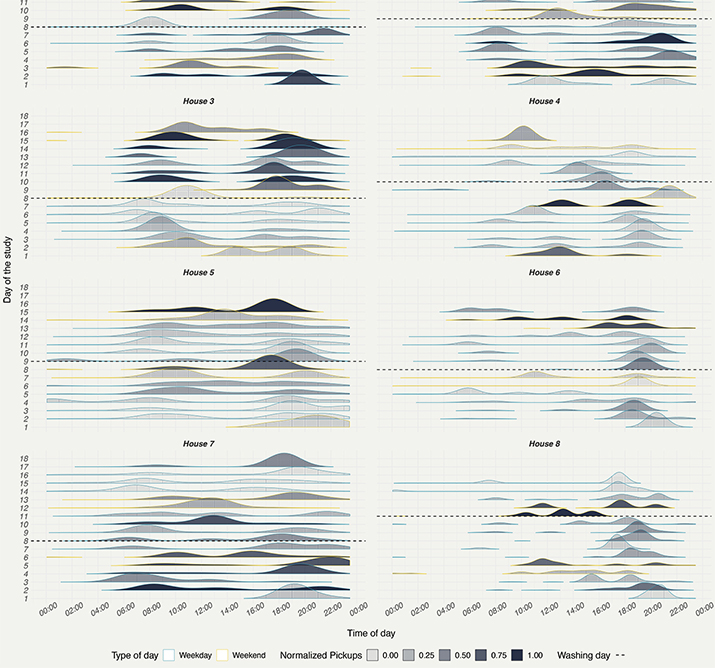

Movement Data Analysis

At the end of the study, we collected the logs from the 8 data loggers and merged them into a single database. In the first round of analysis, to familiarize ourselves with the movement data, we compared the kitchen schedules for each house (Figure 5a) with the raw data logs visualized in R via jitter plots (Figure 5b). This revealed the moments of the day when the participants were using AnimaTo and actively engaged in the kitchen. The density of the distribution of points (each point representing a single movement) in the jitter plot can be considered an indicator of the intensity of use. Moreover, comparing the jitter plots with the previously filled kitchen schedules allowed us to notice any drastic changes in their kitchen use routines (Figure 5a). In the second round of analysis, we utilized density plots to illustrate activity patterns with AnimaTo, as they depict the distribution of the pickup points over time. We used ridgeline plots to compare movement patterns within the same house over multiple days and to compare movement patterns across houses (Figure 5c). For each house, the movement data for each day was normalized using min-max normalization, which gave us an overview of which days corresponded to intensive use of AnimaTo compared to days when AnimaTo was sparsely used. In the plots, the high peaks represent the times of day when the artifact was used intensely (e.g., while preparing a meal in the kitchen), and the high opaqueness corresponds to days when the artifact was used more intensely compared to days when it was used sparsely. As an example in H2, the minimum pickups may happen on the day when the artifact was used the least (days 16 and 17), and the maximum pickups may happen on the day when the artifact was used the most (days 2, 3, and 6). We used the printed version of these plots to support the discussion among the research team.

Figure 5. Example of movement data collected from H2. (a) The kitchen schedule filled in by participants. (b) Jitter plot of AnimaTo’s motion. Each dot represents a single movement of AnimaTo. (c) Ridgeline plot of AnimaTo’s motion. The height represents the time of the day when AnimaTo was used more intensely. The opacity represents which days corresponded to more intensive use compared to days of less intensive use.

Results

The longitudinal study aimed to map the felt experiences with the changes and multiple states of AnimaTo. As a first attempt to conduct an RtD investigation framed within the Materials Experience framework, we organized our findings around the two types of data collected. First, we describe the results of the quantitative analysis for the four levels of materials experience and movement data. Secondly, we present the results of the qualitative analysis, which were obtained through thematic analysis.

Quantitative Results

Sensorial Level

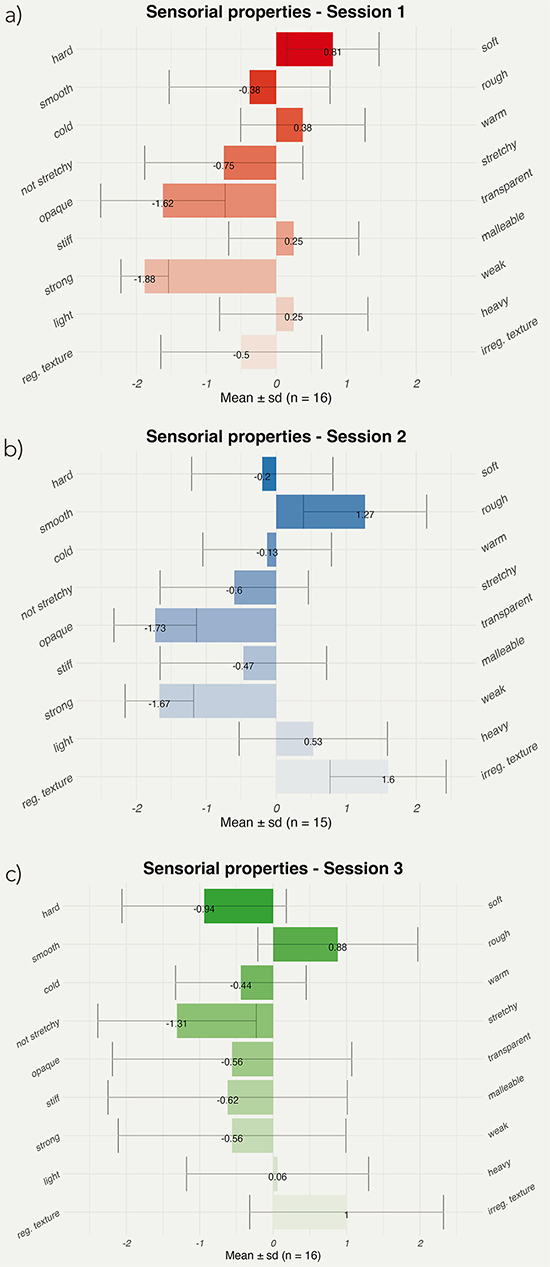

At the sensory level, opinions varied significantly among participants (Figure 6). At the beginning of the study (session 1), AnimaTo was perceived as softer, smoother, more opaque, stronger, and with a regular texture. After one week in session 2, AnimaTo felt rougher and had an irregular texture due to shrinking. At the end of the study in session 3, after washing, AnimaTo was perceived as hard, rough, with an irregular texture, less stretchy, and weaker than in the previous sessions.

Figure 6. Mean values and standard deviation of sensorial properties over the three sessions.

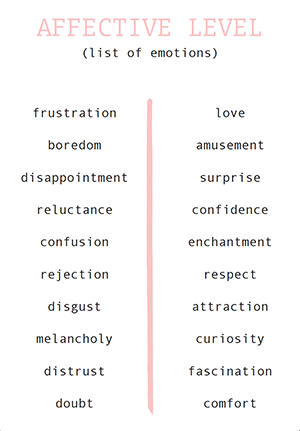

Affective Level

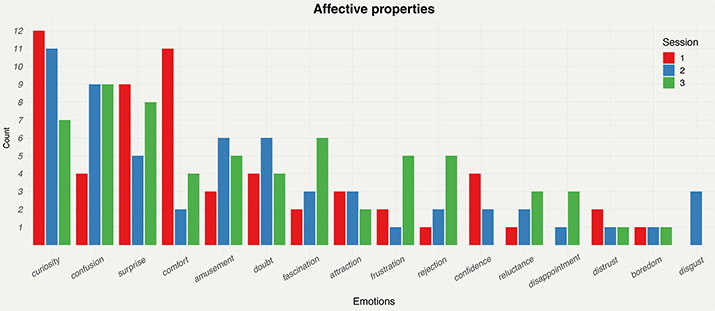

At the affective level, participants expressed the most frequent feelings of curiosity (n = 30), confusion (n = 22), surprise (n = 22), and comfort (n = 17) (Figure 7). Curiosity decreased over time. Instead, confusion increased in the second and third sessions. Surprise was higher in the first and last sessions. Participants never mentioned feeling enchanted or respectful. The most pleasant emotions were confidence (n = 6, mean = 2.16) and amusement (n = 14, mean = 1.71), whereas the most intense emotions were disgust (n = 3, mean = 1.66) and fascination (n = 11, mean = 1.54).

Figure 7. Frequency count of emotions over the three sessions. The plot does not display the emotions mentioned only once: calm, closeness, and love in Session 1; annoyance and strength in Session 2; and melancholy in Session 3.

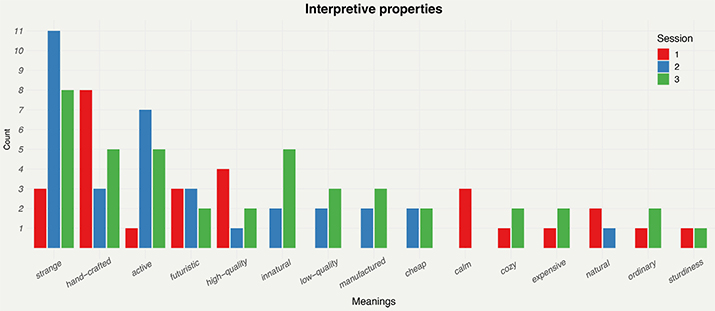

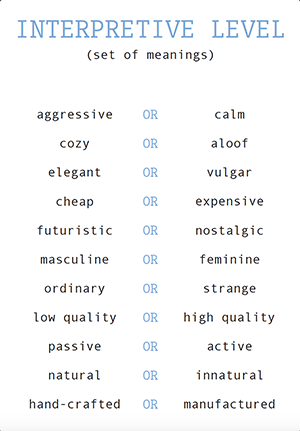

Interpretive Level

At the interpretive level, participants perceived AnimaTo as being most frequently described as strange (n = 22), handcrafted (n = 16), active (n = 13), and futuristic (n = 8) (Figure 8). Strange and active were attributed to AnimaTo in the second session. Hand-crafted was frequently mentioned in the first and last sessions. High quality was often mentioned in the first session (n = 4), whereas terms such as unnatural, low-quality, and manufactured were mentioned in the second and third sessions. Participants never attributed meanings to words such as “elegant,” “vulgar,” and “masculine.” Participants associated AnimaTo with textile objects from the domestic environment (e.g., pot holders, baby blankets, curtains) or garments (e.g., corsets, scarves).

Figure 8. Frequency count of meanings over the three sessions. The plot does not display the meanings mentioned only once: cleaning, comfort, dirty, feminine, good quality, homey, old-fashioned, summery, trendy, and warmth in session 1; aloof, interesting, less cosy, not functioning, reactive, shrunk, unique, and unpractical in session 2; aggressive, compact, nostalgic, passive, unusual, and used in session 3.

Performative Level

Visual analysis of the ridgeline plots of the movement data (Figure 9) revealed the moments of the day when participants were more active in the kitchen (height) and the days over the entire study during which AnimaTo was used more intensively (opacity). For H2, H3, and H5, we observed distinguishable patterns on weekdays versus weekend days (see also the plot in Appendix H). H4 used AnimaTo to the least. The peak increase on day 1, the day before washing day, and the last day of the study are negligible due to the researcher’s visits. During the first week, differences in the intensity of use emerged from the participants’ daily routines and kitchen practices. In households where participants worked away from home, AnimaTo was used only at breakfast, in the evenings, and more frequently throughout the day during weekends (H6). In households where at least one participant worked from home, AnimaTo was often moved around at lunch and dinner (H5, H7). In H3, AnimaTo was used as a drying mat for dishes, resulting in fewer data points in the first half of the study compared to the second half, even when AnimaTo was used. During the second week, the data logs revealed a general tendency to use AnimaTo less after washing. H3 was an exception, as the average number of pickups increased in the second week.

Figure 9. Distribution of the pickups of AnimaTo over the entire study duration.

Qualitative Results

Session 1

On Day 1, participants replaced their tea towels with AnimaTo (Figure 10a-e). Some households used it to dry their hands, while others used it to dry dishes and while cooking. Participants appreciated that AnimaTo looked handcrafted, as a synonym for high quality. AnimaTo was described as soft, smooth, opaque, strong, and with a regular texture. Participants often referred to the thickness of AnimaTo’s fabric, and some thought it consisted of multiple layers (Daniel-H2). They associated AnimaTo with other textile objects from the domestic environment [e.g., pot-holder (H7-Olivia), baby blanket (H8-Megan)], or garments [e.g., jacket fabric (H2-Emma)]. Participants felt curious and surprised by the size of AnimaTo. Some households were intrigued and started speculating on what type of change to expect from AnimaTo: “I hope there is sound coming out” (H6-Sophie). When asked to give a name to the artifact, participants assigned AnimaTo human names, e.g., George (H2) or Kitchen Rani [meaning “queen” in Hindi (H3)], cartoon characters [Coco from Sesame Street (H4)], or nicknames that they found cute, e.g., Doekie (H1) and Poekie (H7).

Figure 10. AnimaTo in the first days of deployment. (a-b) AnimaTo on Day 1. (c-d-e) AnimaTo on Day 4 in different households. In H3 (e), AnimaTo was already almost entirely shrunk.

Session 2

Participants noticed that AnimaTo had started to shrink in the early days of use, and they reported it via pictures. Most households understood that the changes happened in reaction to AnimaTo getting wet. After the initial days, participants observed that AnimaTo would not dry as quickly as it had at the beginning due to the fabric’s thickness (Sophie-H6). For this reason, they felt disgusted or annoyed that AnimaTo would no longer dry well. Emma-H2 associated AnimaTo with an old mop to clean the floors. Emma-H2 also placed AnimaTo on a radiator to dry more quickly, and she expected it to return to its initial, unshrunk state. The day before the session, she wrote, “I’m confused/worried what to do with the towel. I think I’ve killed George [name of her AnimaTo].” While the PVA yarn was still wet, other participants attempted to stretch AnimaTo to return it to its initial state.

In the second session, some participants expressed difficulty rating the sensorial scales because of the heterogeneity of AnimaTo. They still felt curious, but their level of confusion increased. Charles-H5 shared his confusion in a text message on day 6: “Because it doesn’t change how we use it. So shouldn’t there be a bigger change?” AnimaTo was often compared with ordinary towels: “If this [shrinking] would happen to my regular towel at a regular time, I’d definitely be annoyed” (Lucy-H5). Some participants mentioned being more aware of the towel because they wanted to see what would happen every time they used it. James-H7 said, “Every time I was using it, I was conscious I was using it, and that’s different than using a normal [towel], like any other towel that we have.” Differences in modality of use influenced the speed of change. H3-Victoria used AnimaTo to place hand-washed dishes to dry as a drying mat (Figure 10e). Even though AnimaTo was rarely moved from the kitchen counter, the shrinking happened quickly. As shown in Figure 10e, on day 4, AnimaTo had already reached almost its fully shrunk state. In other households, the changes appeared more gradually (Figures 10c and 10d). Some participants mentioned that the reaction in their AnimaTo was not immediate. H2-Emma would dry her hands and walk by the kitchen again after a few minutes to check if anything had happened. The different ways of use also affected how AnimaTo’s shrinking behavior was received. Despite most households sharing a degree of disappointment or frustration, H3 particularly appreciated AnimaTo’s shrunken state because the thicker structure would allow it to absorb more water.

Session 3

During the second week of deployment, participants felt excited about what change to expect on washing day. H3 washed AnimaTo by hand before the expected day. Even though the rest of the houses followed the instructions, AnimaTo showed three unfolding behaviors after washing: unfolding completely [H1, H7 (Figure 11a)]; partially unfolding [H2, H5, H6, H8 (Figure 11b)]; and not unfolding at all [H3, H4 (Figure 11c)]. Probably due to differences in washing cycles among houses, the PVA yarns did not dissolve completely. In H7, participants washed AnimaTo twice because they thought the change was incomplete after the first wash cycle. Despite the differences, all participants were surprised and fascinated by what happened after washing.

Figure 11. AnimaTo’s multiple unfolding behaviors.

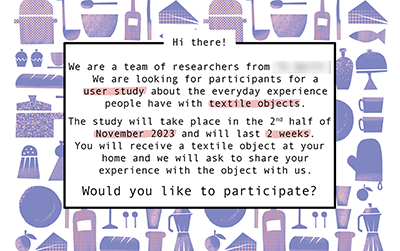

Lily-H1 considered AnimaTo to be of low quality due to the cracking sounds it made when folded. In H1, participants would no longer call their AnimaTo a “doekie” (meaning “a small cloth” in Dutch) because it had become larger. They assigned AnimaTo the new function of a blanket (Figure 12c): “I did not want to use it as a towel anymore because it was too large. OK, so we actually put it on the couch to use this sort of cloth” (Tom-H1). Sometimes, their kids would use it to play and build a fort for their pets (Figure 13c). They also moved AnimaTo around the house, for example, on the railing of the stairs (Figure 12d). Despite participants claiming to be confused, some looked for new functions of the unfolded or semi-unfolded AnimaTo: “The only thing I’m doing with the towel is stretching, touching, feeling the fabric and wonder what a better use [it] can have” (Emma-H2). During the last interview, Emma-H2 also shared that Animato was “[...] strange because of the initial meaning of the towel, but it’s not meant to be a towel because it stays wet, doesn’t dry really good, and when you put this wet towel over the… the heating, it cracks afterwards. So, I think the purpose of the towel is far gone.” Participants in H2 moved AnimaTo around the house to dry on different radiators (Figure 13a) and on the bathroom floor, where it was used as a shower mat (Figure 13b).

Figure 12. AnimaTo in different situations. (a-b) In the kitchen. (c) In the living room. (d) In the hallway.

Figure 13. Sketches of AnimaTo in new situations that were not captured in photos. (a) AnimaTo drying on a radiator. (b) AnimaTo used as a shower mat. (c) AnimaTo used by kids to play with their pets.

Other participants felt confused and frustrated, and almost stopped using the artifact: “[...] at the beginning I was trying to use it more like… like I put all the other towels for laundry. And lately, since this is in a new state, I’m like… I… I’m taking again the other towels and using them because yeah, now it’s not functional [...]” (Emily-H4; Figure 12b). Eventually, also in H4, participants started to use their AnimaTo as a drying mat for other objects (Figure 12a). Lucy-H5 was frustrated because her AnimaTo “just doesn’t do anymore what it’s supposed to do” and admitted that she would have stopped using it if she was not participating in the study. According to Megan-H8, their AnimaTo was no longer usable as a kitchen towel, but she enjoyed tearing it apart and hearing the cracking sounds of dried PVA yarns (Figure 14a-d). The only exception to the general trend is H3. The repeated wash cycles, both by hand and in cold water, made AnimaTo shrink even more. Vicotria-H3 was satisfied with her AnimaTo because it would still absorb water as intended.

Figure 14. Megan-H8 shows how she enjoyed tearing her AnimaTo apart and hearing the cracking sounds.

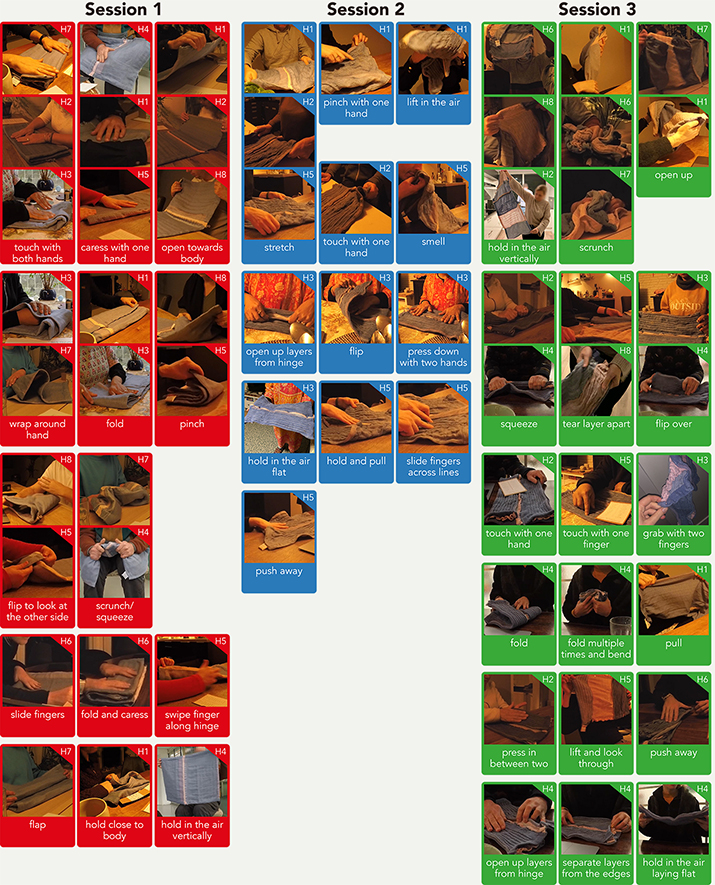

Observations on AnimaTo’s Performativity

At the performative level, the most common and unique actions recorded during the sessions are shown in Figure 15. Generally, in the first session, participants handled AnimaTo with care. Most participants repeatedly caressed AnimaTo’s surface, sliding the tips of their fingers and folding it accurately. During the interview, AnimaTo was held close to their bodies, in front of their chests, when lying on the table or on their laps. In the second session, participants performed actions with less care, such as stretching and pulling the shrunk areas of AnimaTo. In H3, AnimaTo was washed by hand before the indicated washing day, and it shrank to its maximum potential. Here, participants held AnimaTo lying horizontally on their hands, as it would no longer drape. Also, in their AnimaTo, the PVA around the edges started to dissolve. This encouraged participants to pinch and pull the hems along the central hinge to open up the layers. Other participants were attracted by the parallel lines emerging in the shrunk areas of AnimaTo and rubbed their fingers across them. Charles-H5 also smelled the artifact. During the session, some participants kept AnimaTo on the side. Others pushed it away when they no longer needed it to assess its sensorial qualities. In the third session, participants whose AnimaTo had completely unfolded extended their arms in the air to keep it open. When evaluating its sensorial qualities, they squeezed and scrunched it rather than accurately folding it, as they had done at the beginning of the study. Participants whose AnimaTo did not unfold completely tended to stretch it and pull the hems to separate the layers.

Figure 15. Selection of actions performed by participants during the visits. The top right corner of every photo indicates the corresponding household.

Summary of Findings

In summary, we analyzed the materials experience of AnimaTo over two weeks, focusing on its performativity. AnimaTo’s multiple embedded states successfully initiated reflective experiences and invited creative uses over time. In the first week, AnimaTo displayed similar shrinking behavior across all houses, where it was used as a tea towel (except H3). However, in the second week after washing, AnimaTo showed varied behaviors: unfolding completely, partially, or not at all. Generally, curiosity and confusion were the predominant emotions experienced by participants, following opposite trends. Curiosity was initially high and gradually decreased over time, while confusion was initially low and increased over time. We designed a familiar object, a tea towel, to facilitate its adaptation in home settings. This pre-defined function created a certain level of expectation on its functional and aesthetic qualities. The progressive departure of AnimaTo from its initial function created frustration. Some participants were expecting changes to be more extreme or continuous over time. Thus, a critical balance is sought between maintaining the artifact’s expected function and waiting for novel expressions of morphing behavior that would have kept the artifact intriguing and relevant for a longer time.

We designed and deployed AnimaTo to observe whether its MMTF nature, which we argued would enhance its performativity, would open up new possibilities for use towards multi-situatedness. During both stages, AnimaTo invited its users to situate it outside of the kitchen context, as anticipated. Yet, different patterns of multi-situatedness emerged. Only after washing, AnimaTo was taken out of the kitchen in its unfolded (or semi-unfolded) state for other purposes, such as the bathroom and living room. In the following section, we provide a meta-level discussion on the potential reasons and tensions behind users’ materials experiences with MMTF, organized under three themes: function, temporality, and materiality. We extracted these themes within our research team through thematic analysis of all cases. In the following sections, we will unpack these themes by providing examples from our findings and discussing their broader implications for the design research community. To conclude, we will reflect on the limitations of the current study and provide recommendations for future work.

Discussion

On the Role of Function in the Performativity of Multimorphic Textile-forms

While AnimaTo’s shrinking behavior was negatively experienced, participants did not stop interacting with it. The movement data showed that participants were even more active, performing new actions to bring AnimaTo back to its initial state and preserve its tea towel function. These findings relate to the strategy of “disruption of affordance” (Barati et al., 2018, p. 2). In the second week of the study, participants became more used to AnimaTo’s inability to fulfill its function. Some avoided it, and some stopped using it. A few participants began to think of new functions, but generally struggled to find them, feeling confused and disappointed. Their deep emotional engagement was further evidenced by the anthropomorphizing of AnimaTo, with several participants assigning it names such as “George” and “Queen”. Assigning a clear function to AnimaTo negatively affected its materials experience rather than drastically increasing its performativity, especially in its unfolded and open-ended state. This aligns with theories of anticipation and expectation (McCarthy & Wright, 2004). Confirmation or contradiction of a specific expectation generates satisfaction or disappointment, respectively (Demir et al., 2009). Emma-H2’s remark, “I think I’ve killed George”, when her AnimaTo named George shrank and remained wet, exemplifies how users respond when an artifact does not function as expected (Latour, 1993; Norman, 2013). Accordingly, users experienced AnimaTo positively until it stopped functioning as intended. Humans perceive objects as resourceful (Kuijer et al., 2017)—we utilize everyday objects in numerous ways, and when the materials of these objects help situate them in multiple contexts, they become part of various practices (Glăveanu, 2012; Karana et al., 2017). Yet, conventional design practices tend to treat design outcomes as static and are not used to thinking in terms of multiplicity, relegating the users’ role to that of ‘consumers’ and limiting their creativity. Following recent prompts for action on regenerative ecologies with living artifacts, we envision future design practices to disentangle themselves from rigid and constrained thinking to “create situations that encourage creative assemblages, where humans actively participate and coevolve with non-humans within a dynamic ecology of interconnected living and non-living entities” (Karana et al., 2023, p. 4). The main implication of this perspective, substantiated by recent work in practice-oriented design (Kuijer et al., 2013), is that designers should not fully predetermine the value of an artifact within a practice at design time, but rather allow it to emerge during use. As Bredies (2008) argues, irritation from discontinuities can be a productive entry point for such open-ended engagement, inviting users to renegotiate the role of artifacts in practice. This will allow the artifact to generate value at use time, opening up to unanticipated appropriations. Therefore, designers should empower users and support them in noticing the artifacts’ action possibilities, finding a balance of open-ended design outcomes that do not cause users to doubt their abilities.

As advanced by previous research in sustainable fashion, unfinished garments can invite users to complete them, developing feelings of ownership while alleviating the fear of making mistakes (Niinimäki, 2013). For instance, visual cues can guide users in creating and personalizing zero-waste garment patterns (McQuillan et al., 2018) or in customizing and reusing modular smart textile garments through intentional unraveling (Wu & Devendorf, 2020). In contrast to ready-to-use modes of designing textile artifacts and garments, design can support active user engagement rather than passive consumption. Reflecting on AnimaTo’s design, we see opportunities to include transitional functions rather than leaving the last state completely open-ended. For example, the shrunk state of AnimaTo could have included a visual and tactile cue that hinted at the use as a potholder (e.g., a circular and thicker section suggesting insulation). Such transitional functions, leveraging the material affordances of the artifact, could mitigate frustration when the initial function becomes less viable and support users in adopting new uses. By doing so, MMTF will tend to remain personally and socially relevant for extended time frames. This finding opens a space where further research can explore 1) the impact of an initial function when a MMTF is presented to users, 2) the time needed for users to notice multi-situatedness, and 3) the extent to which each embedded state should have a predefined or fixed function. To break free from our preconceived expectations of artifacts, we challenge designers to embrace the fluidity and openness required in both their own practice and in their final design outcomes. By doing so, we could foster a sense of openness in society that would help individuals see materials as more resourceful and, therefore, extend human-artifact relationships.

On the Role of Temporality in the Performativity of Multimorphic Textile-forms

We designed AnimaTo as a MMTF artifact to display multiple changes over its lifespan. Textiles’ impermanence is one of the qualities that makes them emotionally significant to us, as they carry meanings (Karana, 2010) and encapsulate memories over time. Designers leveraged irreversible changes to textile artifacts, such as locally burning, as a strategy to permanently store memories in the material itself (Persson, 2013). However, in MMTF, change happens on a different temporal scale as it is (almost) immediately visible to the human eye. Designers of MMTF possessing a good understanding of the material at hand could fine-tune the timeframe in which changes take place. In particular, they could leverage cumulation, i.e., the tension that arises as an experience unfolds over time (McCarthy & Wright, 2004), and carefully map the temporal qualities of each embedded state to their relative function. By “mapping,” we do not mean prescribing a single function for each state, but rather ensuring that the temporal transitions remain distinct and do not obstruct appropriation. This clarity can support multi-situatedness by allowing users to perceive a range of possible uses across states, rather than being confused by unexpected transformations.

Changes in everyday textiles are often perceived negatively. Depending on the degree of emotional attachment, we dispose of worn textiles quickly or downgrade their function. For example, old shirts might be torn to make cleaning rags, or a worn-out pillow might be used as a bed for a pet. Recent studies in sustainable consumption of clothes proposed ‘craft of use’ as a new fashion experience grounded on practices of preserving and tending garments (Fletcher, 2016). In these examples and in the textile artifacts that surround us daily, change is not intentionally crafted during the design time. Embracing the temporality lens to design MMTF requires us to shift from seeing things as ‘being finished, as completely static’ but rather as ‘things in motion’ (Tonkinwise, 2004). This raises questions concerning how to introduce change to people, the number of embedded states that need to be effectively perceived by users, and the minimum spatiotemporal distance between them that must be perceived as distinguishable states. We invite designers to anticipate how the temporal qualities of change might lead to upgrades in the perceived quality and function. Designers could give users control over the changes across the multiple states of MMTF artifacts, increasing their sense of agency and emotional attachment. Often multifunctional or ‘half-finished’ artifacts such as these require a level of time investment, skill, or risk-taking on the user’s side, which is not always desirable [e.g., McQuillan et al. (2018); Niinimäki (2013)]. We suggest that by building morphing behavior through the material-textile-form system, leveraging its performative qualities, the transformations in MMTF can be made more innate or inherent to the properties of the artifact itself.

Other strategies designers could employ are related to the reversibility of change. In this work, we selected PVA as the active material displaying irreversible morphing behavior. However, by making specific material choices, designers can manipulate the directionality of change and allow for a back-and-forth shift from one state to another, adding an extra experiential level, for example, through recurring movements at seemingly random moments that may cause surprise in people. These considerations can enhance the experience of change and facilitate the integration of MMTF artifacts into everyday life, particularly when their multiple state temporalities and overall lifecycles are aligned with the temporalities of the materials they are made from.

On the Role of Materiality in the Performativity of Multimorphic Textile-forms

The materials surrounding us are expected to feel and perform in specific ways, and textiles are no exception. We have gained this intimate yet universal knowledge through daily interactions with cloth, specifically through its textileness (Buso et al., 2022; Gowrishankar et al., 2017). We expect a blanket to feel thick and heavy, or running leggings to feel stretchy and supportive. We rely on the physical knowledge associated with the various types of textile artifacts that populate our everyday lives to provide a sense of comfort and security. Because we introduced AnimaTo situated in the kitchen, our design choices were dictated by the fact that we would introduce AnimaTo as an identifiable ordinary object, such as a tea towel. The choices made across all the elements of the textile-form system were made to match AnimaTo’s initial function: at a fiber-yarn level, we selected a soft and absorbent material, cotton; at a structure level, we used a twill weave structure for its strength and smooth hand-feel; at a form level, we selected a size for the initial state of AnimaTo comparable to that of ordinary towels. Consequently, the study participants expected AnimaTo’s material qualities to remain constantly ‘tea towel-like’ even though they were aware of the coming changes. By multi-situating AnimaTo through its materiality in both its shrunken and unfolded states, we expected that participants might start using it as a pot holder or shawl. Even though some participants successfully found new uses for AnimaTo in its changed states, all participants shared a comparable degree of doubt. Confusion and disappointment arose because they could not link the new AnimaTo experience to the familiar and known object they were first introduced to, and it was not designed for.

Despite changes at surface, shape, and size levels through shrinking and unfolding, the form component in AnimaTo remained relatively planar throughout the study. AnimaTo, especially after unfolding, consisted of a long rectangular textile reminiscent of a shawl or multiple pieces of cloth assembled together. On one side, the planar form allowed AnimaTo to be perceived as more open to interpretation and, therefore, could encourage patterns of appropriation and resourcefulness, e.g., wrapping AnimaTo around one’s neck. On the other hand, the planar form of AnimaTo in its unfolded state prevented users from seeing it as a ‘real product’, as it appeared to lack a pre-determined function. We could have designed the second stage of AnimaTo material qualities to remind more clearly of an existing textile artifact, e.g., a furry blanket or a canvas shopping bag, but this could have hindered participants’ creativity of use. Therefore, designers of MMTF should carefully consider the material qualities of each state of their artifact, as this determines the overall degree of openness of the artifact and, consequently, its potential for performativity and multi-situatedness.

Limitations and Future Work

This study is our first attempt to systematically map the materials experience of an everyday textile artifact over time and during use. We described the materials experience of AnimaTo both at the moment, i.e., when materials-people encounters occur, and over time, i.e., when performances and collaborations unfold into practices (Giaccardi & Karana, 2015). To document the evolving component of the four levels of materials experience, we digitized the original paper experiential characterization toolkit to collect data during in-person visits and remotely. While we adapted the toolkit’s vocabulary and pictorials for textile qualities, further research is needed to develop textile-specific vocabulary, particularly related to the temporal qualities of textiles, to be included in a textile experience characterization toolkit. Another point to consider is the language used in the study: most participants were non-native English speakers, which may have influenced their ability to articulate their experiences during the visits. Moreover, a few participants had previously attended or conducted design research studies, which might have made them more comfortable in exploring creative uses of AnimaTo. Future work could investigate the role of language and prior research participation in shaping the richness of materials experience accounts.

The documentation and duration of the longitudinal study could benefit from further improvement. The three experiential characterization sessions served as snapshots at the most crucial moments of the study, i.e., the beginning, after the shrinking, and at the end. Moreover, we were unable to record immediate reactions after the shrinking or after washing AnimaTo. Researchers should explore experience-sampling methods such as those used in Vaizman et al. (2018), in which sensory data is recorded through self-report in the wild and in the moment. Moreover, a longer study duration could have led to more inventive uses of AnimaTo in its unfolded state. It could have excluded the novelty effect that might have affected the frequency of interactions.

This study instantiates how performativity can be captured during the use of a material artifact over time through a mixed-methods approach. The experiential characterization allowed us to collect qualitative data at three points in time. The movement-sensing system enabled us to collect quantitative data in a continuous and fine-grained manner. While this combination provided valuable insights, we were unable to record the actions participants performed outside of the visits (unless they were retrospectively reported). Further developments in the sensing system could address this gap. For example, detecting movements of the artifact around the house could be achieved by installing multiple data loggers and using the signal strength to triangulate the artifact’s location (as in Verma et al., 2017). Moreover, future work could conduct in-depth quantitative analysis of the movement data combined with Animato’s states and experiential qualities. For instance, this could reveal how different movement trajectories relate to the resulting Animato’s form, experiential qualities, and ways of use. Lastly, despite the sensing system’s unobtrusiveness, its influence on participants’ expectations and overall experience is still unknown. Acknowledging recent advances in electronic textiles, other seamless technologies could be embedded in the textile artifact. By doing so, the textile artifact itself, through its physical affordances, could also be used for subjective data collection (Karahanoğlu & Ludden, 2021).

Conclusion

This paper explores the opportunity advanced by textiles’ potential to be situated in multiple contexts, serving multiple functions that arise from their unique material qualities, i.e., multi-situatedness. We report on a longitudinal materials experience study of the MMTF artifact AnimaTo. By applying a mixed-methods data collection approach, we gathered insights into how AnimaTo’s materials experience, particularly its performativity, evolves during use in everyday contexts. AnimaTo’s morphing behavior, displayed in two stages through shrinking and unfolding, invited participants to situate it outside the initial kitchen context. However, curiosity diminished as the function of AnimaTo became less apparent, and confusion and frustration took over. Generally, this caused participants to distance themselves from AnimaTo, interact with it less intensely, and, in some cases, stop using it altogether. While we intentionally designed the two distinct stages of AnimaTo to enhance its performativity, we speculate that assigning an initial function negatively influenced perceptions of the artifact in subsequent states and, consequently, its overall materials experience. Discussing these empirical findings, we outline the design implications and considerations for creating MMTF. In particular, we highlight the crucial role of designers in carefully introducing change to people by providing an initial ordinary function to the artifact’s initial state, such as a tea towel. We invite designers to manage the tensions emerging at the intersection of assigning functions to MMTF’s multiple embedded states, tuning the temporality of their morphing behavior, and crafting their materiality to match the expected materials experience. This work represents an initial attempt to investigate the unfolding of the performativity of a MMTF in the everyday life. We suggest a methodological approach to systematically evaluate the evolving components of the materials experience of a textile artifact. Lastly, we expect this work to serve as a basis for building on and expanding ongoing endeavors to minimize the ecological impact of textile artifacts by extending their lifespan through ongoing changes in their states, thereby prolonging their relevance in human-textile relationships.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to the longitudinal study participants for their valuable contributions to this work.

References

- Bang, A. L. (2011). Emotional value of applied textiles: Dialogue-oriented and participatory approaches to textile design [Doctoral dissertation, Kolding School of Design]. Designskolen Kolding. https://adk.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/emotional-value-of-applied-textiles-dialogue-oriented-and-partici/

- Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(3), 801-831. https://doi.org/10.1086/345321

- Barati, B., Giaccardi, E., & Karana, E. (2018). The making of performativity in designing [with] smart material composites. In Proceedings of the conference on human factors in computing systems (Article No. 5). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173579

- Baskan, A., & Goncu-Berk, G. (2022). User experience of wearable technologies: A comparative analysis of textile-based and accessory-based wearable products. Applied Sciences, 12(21), Article 11154. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122111154

- Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822391623

- Bennett, J., Cheah, P., Orlie, M. A., & Grosz, E. (2010). New materialisms: Ontology, agency, and politics. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822392996

- Bergström, J., Clark, B., Frigo, A., Mazé, R., Redström, J., & Vallgårda, A. (2010). Becoming materials: Material forms and forms of practice. Digital Creativity, 21(3), 155-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2010.502235

- Boon, B., Rozendaal, M., & Stappers, P. J. (2018). Ambiguity and open-endedness in behavioural design. In Proceedings of the DRS international conference on design as a catalyst for change (pp. 2076-2085). DRS. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2018.452

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/doi:10.1515/9781503621749

- Bredies, K. (2008). Confuse the user! A use-centred view on participatory design. Retrieved December 12, 2025 from https://mlab.taik.fi/co-design-ws/papers/Bredies_confuse_the_user_pdc08.pdf

- Buso, A., McQuillan, H., Jansen, K., & Karana, E. (2022). The unfolding of textileness in animated textiles: An exploration of woven textile-forms. In Proceeding of the DRS conference (Article No. 208). DRS. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2022.612

- Buso, A., McQuillan, H., Voorwinden, M., & Karana, E. (2023). Towards performative woven textile-form interfaces. In Proceedings of textile intersections conference (Article No. 6) DRS. https://doi.org/10.21606/TI-2023/106