From Technical Support to Lifelong Learning? Reconsidering the Role of Municipal Digital Support Services for Older Adults

Riikka Eskola 1 and Johanna Ylipulli 1, 2, *

1 Aalto University, Espoo, Finland

2 University of Vaasa, Vaasa, Finland

The increasing digitalization of societies necessitates a wide range of digital skills from all citizens. Previous research indicates that certain demographic groups, such as older adults who do not participate in the active workforce or formal education, are vulnerable to falling behind in rapid development. We present a case study focusing on the experiences of older adults with digital technologies and the digitalization of public services in the capital region of Finland. The goal was to produce knowledge that would help cities design better digital support services for elderly residents. The study is based on qualitative data, including interviews and observation notes, analyzed through a theoretical framework informed by digital inequality studies and digital literacy research. Methodologically, our work highlights the importance of adopting a flexible and responsive approach when engaging in research activities with individuals who have experienced marginalization due to technological development. As a result, we challenge the existing service models of digital support. We ask whether designing a more comprehensive approach to improving digital literacy, which would provide possibilities for long-term learning processes, would be more useful than offering technical support for singular use cases through various channels. Finally, we present examples of practical design implications of our work.

Keywords – Digital Inequality, Digital Literacy, Digital Public Services, Digital Support Design, Older Adults, Qualitative Study.

Relevance to Design Practice – Our research highlights the importance of being flexible and sensitive when addressing technology-related issues with individuals who have been marginalized by technological development. We suggest how the ecosystem of digital support services could be redesigned to provide more holistic services for the aging population in rapidly digitalizing societies.

Citation: Eskola, R., & Ylipulli, J. (2025). From technical support to lifelong learning? Reconsidering the role of municipal digital support services for older adults. International Journal of Design, 19(3), 141-156. https://doi.org/10.57698/v19i3.07

Received June 15, 2024; Accepted July 22, 2025; Published December 31, 2025.

Copyright: © 2025 Eskola & Ylipulli. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-access and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: johanna.ylipulli@uwasa.fi

Riikka Eskola is a digital product designer at Reaktor Innovations. She holds a Master of Science (Technology) degree. Her work bridges academic inquiry and industry practice, focusing on design’s role in addressing societal challenges. She currently designs public sector services, where accessibility and inclusivity are paramount to ensure that digital solutions work for all citizens. Her approach combines user research, rapid prototyping, and participatory methods to bring multiple perspectives into the design process. Beyond her practice, she is interested in how digital products and service systems can work together to foster equitable user experiences and support social sustainability.

Johanna Ylipulli is a docent (adjunct professor) in digital culture and a design anthropologist, with a particular focus on urban contexts and the societal impacts of digitalization. She is working as an associate professor of communication studies at the University of Vaasa. With 15 years of experience in navigating the intersections of anthropology, design, and HCI, her work investigates the transformative capacity of urban digitalization and emerging technologies. She is especially interested in participatory and speculative design methodologies that enable communities to conceptualize diverse futures. Her research contests traditional norms and self-evident ‘truths’ by incorporating critical anthropological viewpoints into design and technology development, redefining how we engage with digital societies and smart cities.

Introduction

In today’s increasingly digital society, it can be argued that maintaining and continuously updating digital skills is essential. To ensure universal access to the digital world, it is essential to make a commitment to lifelong learning by establishing education and support networks that are easily accessible, inclusive, and tailored to meet the diverse needs of various populations. Due to their lack of participation in formal education and employment, older, retired adults constitute a particularly intriguing demographic in terms of learning opportunities (Korjonen-Kuusipuro et al., 2022). Further, as stated in the European Union’s 2018 Directive (2018/1808 EU), municipalities and the government bear the responsibility of enhancing the digital literacy of all citizens, even if it is not a component of formal education (Korjonen-Kuusipuro et al., 2022).

However, even in societies that are heavily investing and leaning towards digitalization, such as the Nordic countries in Europe, digital support and lifelong learning opportunities offered for the aging population can be scattered and sparse (Christensen et al., 2022; Gustafsson & Wihlborg, 2021). This is particularly alarming because, at the same time, more and more everyday services (e.g., banking) are becoming accessible only by digital means; moreover, public services such as healthcare and public transportation are increasingly leaning towards digitalization.

The research context of this article is the capital region cities of Finland, one of the Nordic countries, where the challenge described above has been recognized (Korjonen-Kuusipuro et al., 2022; Koskimies et al., 2021); this led us to launch a collaboration project with two large cities of the area, Espoo and Vantaa. The initial aim was to design tentative ideas for better digital support services for older citizens in these two cities during a five-month academic study. Cities did not fund our research, but the funding was provided by a long-term academic project on digital inequalities (“Digital Inequality in Smart Cities”, funded by the Academy of Finland). Collaboration with the Cities was motivated by our urge to conduct research with a real-world dimension. We began our work by negotiating with the city officials in charge of digital support in both Cities to gain an understanding of their challenges and needs. They introduced us to an earlier public sector project on digital support funded by Finland’s Ministry of Finance and carried out between 2021 and 2022. The project, titled “Multi-sited digital support for city residents,” aimed to ease access to digital support services for people living in Vantaa and Espoo, while also providing background information on how the Cities could strengthen people’s digital skills (Koskimies et al., 2021). Through our discussions with city representatives, we determined that the public sector project serves as a much-needed first step; however, a more in-depth understanding of older adults’ experiences and needs regarding digital technologies and digital support is also necessary.

We decided to proceed by following some of the central principles of participatory design (PD) (Björgvinsson et al., 2012; Björgvinsson et al., 2010; Björgvinsson & Karasti, 2012). Although our relatively short study cannot be considered a full-fledged PD project, our initial aims were aligned with PD in the sense that we aimed to co-create ideas for the desired digital support services and foster mutual learning among older adults, service providers, and researchers. Thus, we deemed that encounters enabled by multi-stakeholder workshops would form the backbone of our approach. However, when we began recruiting older adult participants for our workshops, we quickly learned that they were not motivated to participate in this way. At the same time, they were eager to share their mostly negative experiences with digital public services. These affective responses occurred during numerous encounters, prompting us to change our approach and focus on listening to older adults instead of asking them to participate in solving challenges. Instead of co-creation, we decided to follow an approach inspired by design anthropology, in which people’s life-worlds are studied in-depth, and their experiences are interpreted through a theoretical framework in order to open up new design horizons (Gunn et al., 2020; Smith & Otto, 2020; Ventura & Bichard, 2017). PD and design anthropology can be seen as overlapping in many ways: for example, both prioritize user perspectives. However, we understand they have different emphases. Design anthropology leans towards understanding cultural contexts through an ethnographic approach, whereas PD emphasizes collaborative processes that engage stakeholders directly in shaping outcomes (e.g., Björgvinsson & Karasti, 2012; Smith & Otto, 2020).

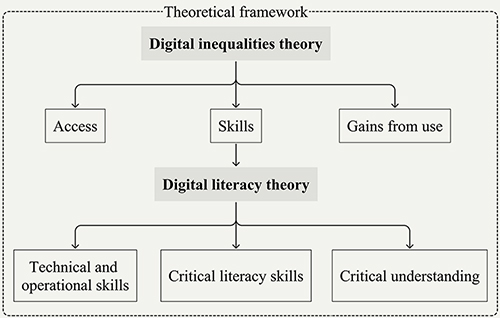

Theoretically, our study is based on combining insights from two different theoretical bodies: digital inequality research and digital literacy research. Based on these two strands of study, we developed a framework that guided the formulation of the interview agenda and the subsequent analysis phase. The framework was also a useful tool for depicting and defining suggestions on how to improve or redesign digital support services offered by the Cities, as it revealed how certain aspects of digital literacy are not adequately addressed in current services. These refer especially to more critical degrees of digital literacy, including critical literacy skills and critical understanding.

In the next section, we provide a brief overview of how digitalization is affecting Finnish society from the perspectives of the public sector and citizens; additionally, we offer a brief overview of the current digital support services available in the studied cities. Secondly, we report our theoretical underpinnings and describe our methods and materials. Next, we present the main results, interpreting them through the theoretical framework. In addition to offering detailed descriptions the digital life-worlds of our study participants, older adults living in a rapidly digitalizing society, our paper discusses three findings: 1) insights on engaging with people experiencing being marginalized by technology development; underlining the need to stay flexible and responsive during the research process; 2) proposition for new design horizons, indicating the whole concept of public digital support targeted for older adults might need to be redesigned; 3) implications for design, offering more incremental suggestions on how to improve municipal digital support offered for our target group.

Accelerating Digitalization and Finnish Public Services

Finland has made significant investments in digitalizing its services, as evidenced by its impressive statistics. For example, Finland received the highest score (69.6) in the European Union’s Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI 2022) comparison, indicating a high level of digital competitiveness. The Finnish government is committed to enhancing technology capabilities in the public sector and promoting collaboration between the public and private sectors, in line with its overall goal of advancing digital evolution (Ministry of Finance, 2023).

Finland, as a Nordic welfare state, provides all citizens with access to a comprehensive range of public services, including public healthcare, education, childcare, and cultural and sports facilities. Finnish municipalities bear significant responsibility for providing these public services (Moisio et al., 2010; Ylipulli & Luusua, 2020), and their strategies shape the overall trends in service development. The Cities of Vantaa and Espoo have incorporated digital advancements into their municipal strategies. Vantaa’s municipal strategic plan, “The Vantaa of Innovations,” prioritizes digitalization of public services, envisioning improvements in accessibility, quality, and efficiency (City of Vantaa, 2021). Similarly, Espoo’s municipal strategy, “The Espoo Story,” emphasizes the digitalization and utilization of emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and robotics, to streamline public services (City of Espoo, 2021). Compared to Vantaa, Espoo’s strategy states more directly that cost savings are one key driver in public service digitalization. According to Espoo’s strategy,

[In service development], we will promote social innovations, resident-, customer- and partnership-based activities, effective service provision, improved productivity, as well as cost savings. With the help of digitalization, we will increase the openness of our activities, develop new platform solutions and speed up service processes. (City of Espoo, 2021.)

When it comes to digital support services, the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture (2019) is responsible for providing media education for all age groups. Media education aims to enhance an individual’s media literacy, ability to understand and create various media forms (The National Audiovisual Institute, 2024). Hence, media education is an important part of civic education and is defined as a component of civic skills (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2019). However, the Digital and Population Data Services Agency is tasked with promoting digital support solutions across Finland. This involves educating digital support providers from municipalities and NGOs, coordinating the development of digital support services, researching digital support solutions and the level of digital literacy nationwide, and establishing standard practices for digital support. The agency’s efforts aim to benefit municipalities, NGOs, and various stakeholders (Korjonen-Kuusipuro et al., 2022). In terms of designing and improving digital support services, the Finnish nationwide approach can be described as a top-down approach.

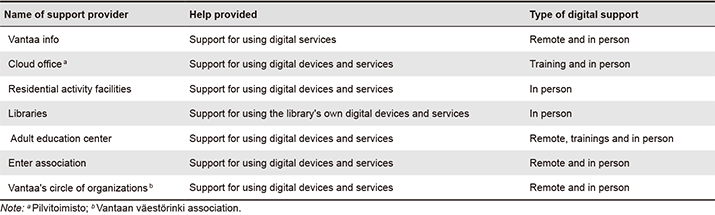

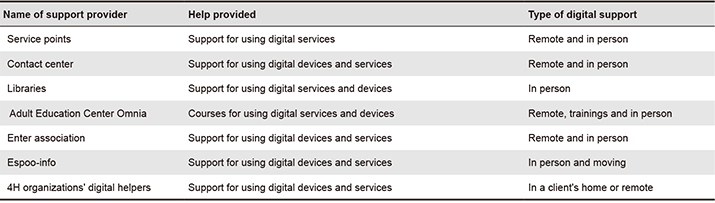

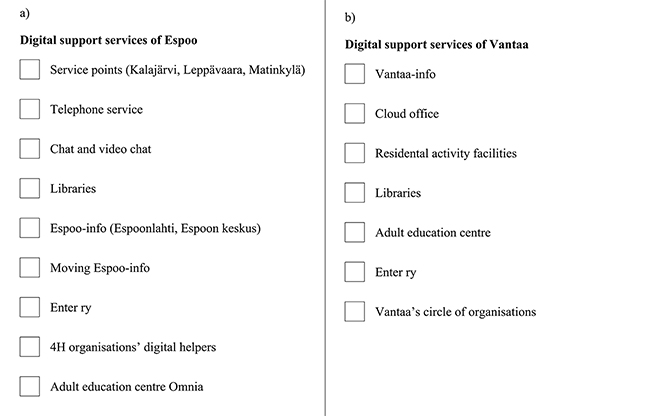

The available digital support services in both Vantaa and Espoo can be described as fragmented (see Tables 1 and 2). In both cities, similar types of digital support are provided through multiple services that focus on helping individuals use their devices and online services in specific use cases, i.e., they offer technical and operational support. The services are managed by different service providers, with no centralized guidance for citizens seeking digital support. In a study on IT helpdesks conducted by Christensen et al. (2022) in the Nordic context, it was found that there is a lack of clarity among various service providers regarding their understanding and communication of their offerings and locations. This has resulted in, for example, citizens being directed increasingly to public libraries with issues that are beyond the scope of a particular support service (see also Gustafsson & Wihlborg, 2021). In Espoo and Vantaa, third-sector actors, such as NGOs, play a significant role in providing digital support services. Christensen et al. (2022) also highlight that collaboration between municipalities and third-sector actors can leverage the strengths of both parties. Municipalities offer organizational capacity and necessary infrastructure, while volunteers provide a digital support service with greater flexibility.

Table 1. Digital support services in the City of Vantaa.

Table 2. Digital support services in the City of Espoo.

The earlier public sector project, “Multi-sited digital support for city residents,” which provided some background information for the study reported in this paper, aimed to develop a service model for Espoo and Vantaa to offer better access to digital support services and improve citizens’ digital skills. Developing the service model involved citizen consultation, a typical approach for public sector development activities (Design Council, 2013). According to Pirinen et al. (2022), many governments and cities worldwide use citizen-centered and collaborative design approaches to address the complex challenges in the public sector, driven by demographic, social, environmental, and economic change. However, this previous project did not explicitly incorporate any elements drawn from design fields, so we aimed to explore how our design expertise could assist the cities with these challenges. The citizen consultation of the project focused on five groups of people: 1) youth (11-24 years old), 2) working citizens, 3) retired citizens, 4) long-term unemployed citizens, and 5) immigrants. The residents’ needs and views regarding digital support were gathered through an online survey (n = 668), mail surveys (n = 286), and phone interviews (n = 50). The results highlighted that older and retired residents, in particular, require digital support and would prefer to receive it in person (Espoo Esbo & Vantaa, 2023; Koskimies et al., 2021). Despite this earlier project having produced some interesting results and suggesting improvements mainly to existing services (see Tables 1 and 2), the city officials emphasized the need for a deeper understanding of how older people interact with digital technologies and digital public services in their daily lives.

According to Pirinen et al. (2022), cities face significant challenges in defining appropriate target groups and reaching actual citizens, as they fear that focusing on too narrow customer segments may lead to unsuitable solutions, since public services need to cater to a diverse set of citizens. Moreover, engaging citizens is resource-intensive, requiring substantial time, financial resources, and expertise. Cities are addressing these issues in diverse ways, and the City of Helsinki, for example, which is part of the same region we studied, has addressed this issue by establishing a pool of citizens that can be contacted at a low cost per person (Hyysalo et al., 2019). Thus, our assistance in engaging with the older people to develop better digital support was welcomed by the Cities of Espoo and Vantaa.

Dimensions of Digital Inequality and Digital Literacy

The theoretical framework (Figure 1) used in this study draws from two distinct yet interconnected bodies of work: digital inequality research and digital literacy research. We decided to build a combination of these two because we wanted to gain a comprehensive understanding of our study participants’ digital life-worlds; we deemed it important to consider both the intersecting social inequalities and the different aspects of digital literacy, ranging from operational skills to a broader understanding of technology and society. Further, some prominent scholars of the field(s) have argued that these two areas have become detached (Helsper & Eynon, 2013). Naturally, assembling two broad theoretical traditions results in the loss of some nuances. However, we considered their central configurations, especially from the perspective of our context and focus: how the public sector should design digital support services for older adults in the context of a highly digitalized and heavily public service-oriented Nordic welfare state.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework of the study depicting dimensions of digital literacy and digital inequality.

According to Robinson et al. (2015), digital inequality is a relatively new type of societal inequality that interacts in many ways with more traditional forms of inequality, such as those based on age, gender, income, or educational attainment. Helsper (2019) defines it as the unequal distribution of digital technologies, skills, and advantages from using them. Digital inequalities have a profound impact on people’s opportunities in society and overall well-being, affecting daily life on multiple levels. Digital competencies are essential for accessing basic services and for acting independently, particularly in rapidly digitizing societies (Helsper, 2021; Ylipulli & Luusua, 2020). Because of their stage of life, older people tend to use more public services, such as health and social benefits, and if these services are increasingly being provided online, sufficient support should also be provided. Research from the Nordic region, however, shows that the growth of digital assistance is not keeping up with the rate of digitization. According to Christensen et al. (2022), this may exacerbate digital inequality and provide difficulties for Nordic welfare societies.

Digital literacy encompasses a wide range of technical and operational abilities required for efficient use of digital devices, software, and information. Typically, the concept also encompasses the skills required to produce various forms of media expression, comprehend and analyze the content, and maintain one’s online identity and presence (Hinrichsen & Coombs, 2013; Martin & Grudziecki, 2006). According to some academics, critical thinking abilities—which include the capacity to evaluate how technology affects both one’s own life and society at large—should be given more emphasis in digital literacy programs (Pangrazio, 2016; Toscano, 2011; Ylipulli & Vigren, 2023).

By utilizing a theoretical framework that incorporated insights from both research traditions, we aimed not only to understand the everyday digital experiences of older adults but also to begin conceptualizing the future digital support services offered by the public sector. Below, we provide a detailed explanation of the different dimensions of our theoretical model, organized under access, various types of digital literacy skills, and benefits from use.

Access

Digital inequalities emerged as a research subject in the 1990s, with the ‘first-level digital divide’ as the focus—referring to access to the Internet and desktop computers (Van Deursen & Van Dijk, 2019). Despite the commodification of computer technology, unequal access to digital resources remains a crucial issue. According to recent statistics, 7% of households in Europe still lack access to the Internet; however, the situation is more favorable in Finland, where 98% of homes have Internet connectivity (Eurostat, 2022).

Overall, access must be understood in a nuanced way, rather than as a binary scale, where it either exists or does not exist. According to Helsper (2021), three elements are influencing both potential and actual access: 1) quality, 2) ubiquity, and 3) autonomy. Quality pertains to the speed and reliability of the connection, as well as the equipment’s performance. Ubiquitous access refers to the ability to connect to the Internet from any location and at any time, regardless of physical location. Lastly, autonomous access refers to the ability to utilize the Internet independently, without dependence on or control by external entities. Acquiring and maintaining the essential equipment for this task sometimes entails significant costs (Helsper, 2021). This article uses this definition as a base for our understanding of access.

Furthermore, technology adoption theory suggests that a person’s motivation, opinions, and perception of potential risks can significantly impact their ICT use (Davis, 1989; Heponiemi et al., 2023). Studies have demonstrated that people who have a pessimistic outlook on digital technology and internet services tend to prefer face-to-face interactions (Helsper, 2021). Finally, we must note that the meaning of ‘accessing the digital realm’ has changed. This is a result of the ongoing development of ICTs and the Internet (Lutz, 2019). Artificial intelligence, 5G network, together with the constantly evolving Internet of Things (IoT), are setting new standards for ‘everyday’ access.

Digital Literacy Theory

In order to properly utilize digital services, one must possess a variety of skills, including technical and operational skills (Van Deursen et al., 2017), as well as skills in critical thinking, such as a knowledge of technology’s impact on contemporary society (Toscano, 2011; Iversen et al., 2018). Proficiency in both skill sets is essential for navigating the digital domain and participating in digital society. For example, Erstad (2015) and Sefton-Green (2013) argue that digitally literate individuals possess the ability to effectively utilize digital technology to achieve their objectives, while simultaneously adopting a critical mindset and understanding the symbolic and cultural implications of such technology.

Technical and Operational Skills

In digital literacy studies and education, technical and operational abilities are typically given higher weight (Pangrazio, 2016). Functional and operational abilities are perceived as more tangible and easier to teach and assess than critical literacy skills, which may be one explanation for this (Helsper, 2015; Pangrazio, 2016). Drawing from Van Laar et al. (2017), technical skills can be defined as follows: Firstly, technical abilities encompass the ability to effectively operate computers, phones, and other digital devices, referring to the ability to comprehend the characteristics of different devices and applications. Technical and operational skills also include information skills, sometimes referred to as information literacy. According to Van Laar et al. (2017), these abilities encompass the capacity to seek, organize, and select knowledge and information from various sources to accomplish a task. In such situations, informed decision-making is required to select the most reliable information sources. Furthermore, effective communication skills are also essential for achieving technical and operational proficiency. Van Laar et al. (2017) define communication skills as the utilization of digital technology to convey information and diverse ideas to oneself or unfamiliar audiences.

Critical Literacy Skills

According to the European digital competence framework for citizens (Van den Brande et al., 2019), digital skills must also encompass the ability to critically generate content, assess information, and utilize social media effectively. These critical literacy abilities include selecting and comprehending the source of information, identifying reliable sources, engaging in dialogues, and ensuring that one’s opinions are acknowledged (Helsper, 2021). Eshet (2004) argues that critical literacy encompasses a range of cognitive, physical, sociological, and emotional abilities on a more personal level. Self-efficacy, or the belief in one’s abilities and capabilities, is an important emotional skill in digital literacy (Helsper, 2021). It is essential to recognize that sociodemographic characteristics impact self-efficacy, which often reflects one’s usual social position rather than a direct measure of one’s ability to perform a task. Gecas (1989) asserts that a high level of self-efficacy increases the likelihood of trying new things and learning by experience. Although self-efficacy can aid in learning new skills, it is also possible to be highly self-efficacious yet lack sufficient critical, technical, or operational digital literacy. This may result in a lack of awareness of one’s own limitations (Broos & Roe, 2006).

Critical Understanding

Some scholars go beyond these definitions and stress a broader, societal dimension of digital literacy: According to Toscano (2011) and Iversen et al. (2018), there is an increasing need to foster social awareness of technology’s role in societal, political, economic, and environmental issues. It refers to having an understanding of how these areas intersect and affect each other, i.e., understanding the place of technology in society at large and how it affects one’s own life and activities. An everyday example of this is recognizing the general logic of data collection—how data is collected online, sold, and monetized (Zuboff, 2019). Critical understanding serves as a basis for participating critically, inquisitively, and constructively in technological advancements. Importantly, comprehending all the technical details, such as the workings of algorithms, is not a prerequisite for this dimension of digital literacy to flourish. This type of digital literacy does not have a settled name. However, different authors have referred to it, for example, as technological understanding (Ylipulli & Hämäläinen, 2023), computational empowerment (Iversen et al., 2018), or radical digital citizenship (Emejulu & McGregor, 2019). Toscano (2011) contends that to create digital technologies for human benefit effectively, one must go beyond the presumption that technologies are inherently advantageous and have a more critical outlook. We consider the dimension of digital understanding to be so central that it is depicted as a separate entity in our framework (Figure 1). This means extending the typical digital literacy frameworks, similarly to Ylipulli and Hämäläinen (2023).

Gains from Use

Digital literacy and accessibility become apparent through the use of technology. According to several scholars, the typical levels of technology engagement are non-use, potential, basic, and advanced use (see, e.g., Livingstone, 2003; Warschauer & Matuchniak, 2010). Non-use refers to individuals who are completely isolated from the digital world, either due to a lack of access or a deliberate decision not to engage. Potential use refers to circumstances in which people’s access to technology and the Internet is restricted. Basic use refers to those who use technology for routine tasks such as emailing, social media use, or internet browsing. Advanced use refers to utilizing technology for more complex tasks, such as software design or programming.

Furthermore, it can be beneficial to categorize the aspects of people’s lives that relate to the use of digital tools and platforms. Scholars such as Blank and Groselj (2016) and Van Deursen and Van Dijk (2014) classify use into five categories: economic, educational, political/civic, social, and creative/leisure use. The economic use of ICT encompasses banking, e-commerce, and shopping, which are becoming increasingly common as more people opt for online shopping. On the other hand, educational use includes online courses, e-books, and educational apps. Political and civic uses include voting, advocacy, community organizing, and engaging in political discussions on social media. Moreover, the creative/leisure use of ICT encompasses social media, gaming, and digital art, which enable users to express themselves, interact, and have fun. Finally, social and communicative use of ICT concludes with messaging, video calling, or social media to connect with friends, family, and others. In general, understanding these different types of technology use can shed light on how technology affects various aspects of our lives.

Engaging with the surrounding digital realm has different consequences for different people. Helsper (2021) suggests that one should examine the fair distribution of opportunities rather than solely focusing on unequal outcomes; structural inequalities often result in unequal outcomes. An individual’s resources outside of the digital sphere also influence how they interact with digital technologies. Therefore, when talking about the effects of ICT use, one should consider a person’s background and the societal context (Helsper, 2021). Following Van Deursen et al. (2017), people are not causing digital inequalities in terms of outcomes by acting differently online and reaping different benefits. Rather, these disparities arise from the fact that different people who engage in the same online activities get different outcomes.

According to Desai et al. (2022), older adults value especially practical gains, such as convenience and ease of use, when using technology. Similarly, Kainiemi et al. (2023) found that older adults perceived the strongest benefits from digital health and social services that were easy to use regardless of time and place, indicating the importance of convenience and accessibility. People can benefit from online interaction in several ways, including developing strong relationships, enhancing their sense of worth, achieving financial savings, accessing employment opportunities, and contributing to good causes (Van Deursen et al., 2017). However, unanticipated events might occur, which could lead to financial fraud, identity theft, discrimination, or bullying (Helsper & Smahel, 2020). ICT use can have an impact on one’s personal well-being as well as their economic, social, and cultural resources (Helsper, 2021). The results of ICT use are also influenced by the type of engagement (Helsper, 2021); for instance, using ICT for investing will probably result in financial gain for the user.

Methods and Materials

According to the public sector project preceding our study, “Multi-sited digital support for city residents,” older adults experienced a greater need for in-person digital support. They had more difficulties and concerns when using digital technologies than other studied groups. Many of the older adults had never heard of digital support services, or they had tried to obtain digital assistance but had not been successful. (Koskimies et al., 2021.)

To start tackling these issues, we decided to draw from participatory design (PD); we had planned to operationalize our approach by arranging a series of multi-stakeholder workshops in which digital support services would be co-created together with the older adults to better meet their needs (e.g., Björgvinsson et al., 2012; Björgvinsson et al., 2010). This approach, however, turned out not to be feasible. We promoted our workshops and approached our target audience in public spaces, such as libraries and community centers. Digital support is often offered in these places, and our idea was to reach older adults who were on their way to seeking help in using digital devices or services. During the intended recruitment period, we did have numerous encounters with people belonging to our target group. They invariably and extensively shared their experiences with digital services and opinions on the ever-digitalizing society, but they were not interested in participating in workshops. They stated that this was because they were frustrated with the increasing digitalization of everyday services, as well as the lack of comprehensive and easily accessible digital support. Interestingly, we were sometimes confronted with quite affective and negative reactions, and the whole concept of digital technology seemed to activate unease and protest, which had not been our intention at all.

These encounters made us understand two things: Firstly, we had severely overestimated our understanding of how older adults experience digitalization in their everyday lives, especially how they experience being marginalized by technical development as digitalized services become inaccessible for them; secondly, our hypothesis concerning that there was a dire need to redesign digital support services was correct. In other words, we had recognized the phenomenon, but our ideas on how to engage with older adults did not work. Thus, we took a step back and deemed that individual, in-depth theme interviews are needed to provide a more solid understanding of the everyday digital experience of older adults living in Espoo and Vantaa, and to redefine our design problem(s) and subsequent approaches. Thus, we decided to draw more from design anthropology, which emphasizes an ethnographic approach and the meaning of contextual and theoretically informed understanding as a basis for design activities (e.g., Gunn et al., 2020).

Data Collection

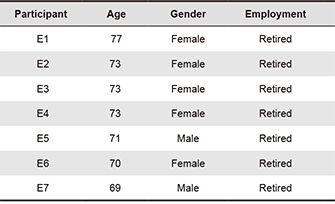

The study is based on qualitative data, consisting of one primary dataset and two secondary datasets. The primary data comprise 14 semi-structured thematic interviews, each lasting approximately one hour. The interviews were carried out with senior citizens between 62 and 77 years old (see Tables 3 and 4). Each interview consisted of five sections (Table 5), each having a different objective. Each section was covered during one interview, but the order and wording of questions varied in each interview.

Table 3. Senior citizen interviewees from Espoo.

Table 4. Senior citizen interviewees from Vantaa.

Table 5. Interview structure and objectives.

Furthermore, the two secondary datasets consist of 1) ethnography-inspired fieldnotes collected during the beginning phases of the project, when senior citizens were recruited on-site for the semi-structured interviews. The fieldnotes focus on describing interactions between the researcher and individuals belonging to the target group but were unwilling to participate in interviews. Further, we conducted 2) three semi-structured thematic interviews with actors providing digital support services for senior citizens, after the collection of the primary dataset. The interviews with digital support providers covered topics such as the particularities of providing digital support for older adults and thoughts on how digital support services should be organized and developed. All data was gathered during January and February of 2023. All the interviews were also audio recorded and later transcribed. This resulted in over 16 hours of recordings and approximately 270 pages of transcriptions.

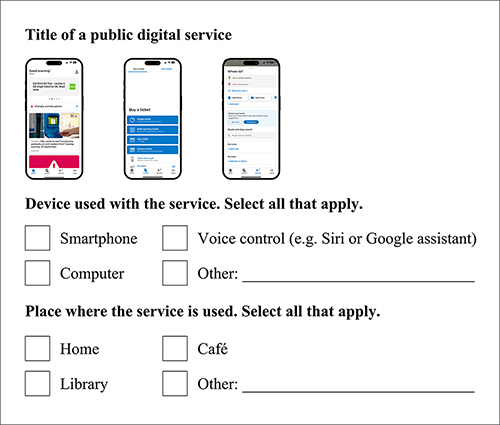

During the interviews with senior citizens, we utilized visual aids (Comi et al., 2014) to elicit comments and generate richer data (see Figures 2, 3, and 4). The visual aids were used as a cognitive aid in phases 2-4 of the interview (Table 5). The first visual aid (Figure 2) consisted of 16 cards, each showing one digital public service available in the interviewee’s city. The researcher asked the interviewee to review the cards and divide them into two piles: the services the interviewee currently uses and the services they do not use. If the interviewee had used a service presented on a card, the researcher asked them to mark where and with which device they used the service.

Figure 2. Template of a visual card about a public digital service.

The second visual aid (Figure 3) was a visual list of currently offered digital support services in the interviewee’s city. The researcher showed the list to the interviewee and asked questions related to challenges with digital technology, received digital support, views on digital support, and potential experiences with municipal digital support, as well as thoughts on improving municipal digital support.

Figure 3. List of municipal digital support services in a) Espoo and b) Vantaa.

The third visual aid (Figure 4) consisted of five contemporary technological phenomena: cookies, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), artificial intelligence, smart cities, and nursing robots. The researchers selected the five phenomena based on their relevance to digital society and their prominence in the news. Cookies are connected to data collection practices online and the data economy, and the GDPR primarily focuses on personal data and privacy. The latter three phenomena have multiple connections with the economy, social and cultural aspects, and environment, and they have been continuously discussed in Finnish media. Each phenomenon was presented on a card, and they were used to probe the interviewees’ familiarity with the technological concepts and to initiate discussions on the technology’s role in society. This part of the study was the most experimental; we aimed to investigate how visual aids can assist in exploring the level of critical understanding as a part of digital literacy (see Figure 1). The rationale for this approach lies in the fact that it is often difficult, if not impossible, to ask directly about abstract and broad issues such as ‘technological understanding’ in a research interview; thus, the selected phenomena and accompanying visual cards acted as a gateway to access study participants’ perceptions on digital technology’s role in society.

Figure 4. Example of a visual card about one contemporary technological phenomenon.

Data Analysis

All the interview transcriptions and fieldnotes were analyzed using qualitative content analysis, as it facilitates new insights or expands the researcher’s understanding of a particular phenomenon (Krippendorff, 2019). To be more specific, we employed a directed approach in this study, referring to the use of existing theory or prior research to create initial coding categories (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Directed qualitative content analysis was well-suited to the study’s general objective of creating a holistic understanding of the digital life-worlds of older citizens, as well as its aim to explore the usefulness of the framework itself and whether theories on digital literacy can be extended to include the category of critical understanding. We first categorized the data under seven predetermined categories, drawn from the theoretical framework and interview objectives, including: 1) Digital inequality-access, 2) Digital inequality-skills and digital literacy, 3) Digital inequality-gains from use, 4) Experiences with digital technologies, 5) Coping with digital technology challenges, 6) Experiences with public digital support services, and 7) Views on developing public digital support. If any data fell outside of these categories, we added a new category to the table. Further, we used sub-categories to gain more nuanced insights: for example, the main category 2) Digital inequality - skills and digital literacy included sub-categories on different digital literacy types. After completing the coding of the primary data, we integrated the analysis of the secondary data to enhance the findings of the primary data.

We carefully considered the ethical aspects, and each participant received detailed information on data protection, a consent form, and a background information form in print. All these forms are in line with the instructions provided by our university. All the information was also verbally explained to the participants at the beginning of the interview, and they were told they could withdraw from the study at any point. We report the basic background information on the age and gender of the participants; however, the data have been anonymized during the initial phases of the analysis process.

Results

Abundant Access

The majority of our interviewees stated that they are satisfied with their access to digital technology. All of them had a mobile phone with an Internet connection and an Internet connection at their home. In addition, 13 out of 14 participants had a computer or laptop at home, and only two interviewees (V7, E2) felt they would need more digital devices. Only one interviewee from Vantaa (V3) reported that the quality of her access (cf. Helsper, 2021; Lutz, 2019) is not good; she mentioned that a slow network at home complicates her ICT use. Perhaps surprisingly, some participants (V5, V6, E5) mentioned that they have other, unused digital devices laying around in their homes. The reasons varied from devices being broken to forgotten passwords; it seems that errors and problems were difficult to solve for them. On the other hand, the older adults did not necessarily even have an urge to fix the issues.

According to previous research (e.g., Helsper, 2021), attitude can pose an obstacle to access. This did not seem to be a significant issue for our participants, as only one (E1) directly mentioned having a negative attitude towards digital technology, and another (E3) stated that she tries to minimize her use of ICT. Overall, these results reflect the digital realities of a relatively wealthy, highly digitalized society. The lack of ownership and access does not define technology use, but differences are connected to other levels of digital inequality and digital literacy.

Fragmented Digital Literacy Skills

Intersecting Factors Affecting Technical and Operational Skills

The workings of older digital devices were familiar to many, for example, due to their work experience before retirement, which highlights the need for an intersectional approach to digital inequalities and consideration of other factors beyond age. On the other hand, some still lacked basic technical skills needed to operate in the current digital world—for example, a few interviewees clearly did not know how to use the new smartphones: V1 complained that she was “so annoyed with this smartphone. This one (a new Samsung phone) has a lot of different stuff. When I had a Nokia phone, it was very clear.” E1 had also experienced difficulties with her new smartphone, which had prevented her from using it for several months.

When the participants from Espoo were asked to assess their own functional skills, many considered them sufficient and believed they could complete tasks independently online (E2, E3, E4, E5, E7). Two of the Espoo participants reported lacking functional skills, such as creating a file, installing applications on a smartphone, or managing multiple passwords. There was a clear difference between the cities: in Vantaa, more participants reported to us that they lacked functional skills. Only two individuals (V4, V7) were confident in their ability to accomplish everything they wanted to do online. The rest experienced various difficulties, connected to tasks such as transferring files from their phone to a computer (V1, V3), not being able to download a desired application (V6), or files from the Internet (V1). It appears that the distinct economic profiles of these two cities are reflected here, even though our sample size is small: Espoo is well-known for its ICT sector companies and knowledge economy, whereas Vantaa has a large number of food, engineering, and machinery industries (see Kuntaliitto website: https://www.localfinland.fi/).

Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that almost all our interviewees in both cities expressed a positive attitude towards learning new functional skills related to digital technology, especially if the skills are perceived as necessary for everyday life. Many underlined the importance of repetition in learning to master new skills. Interviews with digital support services providers supported these findings, as they mentioned that older adults often lack basic functional skills, such as using a smartphone, logging in to email, or managing passwords.

Low Self-efficacy and Drastic Differences in Critical Skills

As mentioned in the theoretical section, self-efficacy, i.e., the belief in one’s abilities and capabilities, can be understood as an important emotional skill and as a part of critical digital literacy (Helsper, 2021). In the interviews, lack of self-efficacy was recognized as an obstacle to using digital technology. Some participants were afraid of making mistakes and facing unwanted consequences. For example, E1 hesitated to install anything on her smartphone due to concerns about getting hacked or other negative consequences; similarly, V4 had not installed email on his phone since “Email tends to be such a service that the hackers spy.” V1 said that she fears getting stuck in the middle of something. Some also feared appearing silly in the eyes of others if they tried out online meeting platforms without adequate experience, for instance. This lack of self-efficacy was partly due to concerns about cybersecurity, which several participants in both cities mentioned. The interviews with digital support providers reinforced this view, and they mentioned that the fear of cybercrimes has been increased, probably due to recent news headlines on the topic.

Other critical skills that can be seen as relevant to our participants include the capacity to generate content critically, assess sources of information, and utilize social media in various ways, both for sharing content and engaging in discussions. Here, the level of skills differed greatly among the participants: most of them used at least one social media, typically Facebook, but the use varied from just passive scrolling to belonging to “absurdly many groups” (E6) and being an active content creator. Often, these more active individuals also expressed the capability to evaluate content, mentioning, for example, the differences between content published in public social media groups and private conversations taking place on WhatsApp or via email. On the other hand, more passive users or those who were not using social media at all expressed confusion or irritation towards the typical communication patterns that take place on these platforms.

Societal Facets of Digitalization: Distant yet Interesting

We explored our participants’ broader digital understanding by asking them about selected technological phenomena that are not easily defined and can be seen as connected to numerous economic, social, political, and environmental issues, as explained in the Methods and Materials section. The approach proved to be quite effective, yielding rich results summarized below.

Many of the participants recognized that cookies relate to following one’s interests and/or receiving more advertisements. Most of them lacked more in-depth knowledge, and some expressed directly that they would like to understand better how cookies work, as they encounter them frequently online. Overall, the lack of understanding was experienced as frustrating. Some refused to accept unnecessary cookies. However, on the contrary, V6 was one of the examples who believed that accepting all cookies is mandatory if she wishes to enter a webpage. GDPR was already a more distant phenomenon, and the researcher needed to explain its meaning to half of the participants. However, after they understood that it was connected to data rights and privacy, almost all of them thought it was a very positive thing. A few participants reflected on online data collection practices and pondered the connection between extensive data collection and businesses and the economy.

Roughly half of the participants were unfamiliar with artificial intelligence (AI), although they recognized that it has been frequently discussed in the media. They raised concerns about whether it is needed for anything and if it is given too much power: “It [AI] puzzles me, I haven’t familiarized myself with it.—It is puzzling what people can achieve through AI, and with AI, it can write a novel, it can sing a song, and so on.” On the other hand, a few (E2, E5, V6) considered that AI can also be useful. For example, E5 stated that many services should be developed intensively by using AI and automation, but also reminded that “In all services related to security and health, one needs to be extremely careful when developing an AI-based software.”

Over half of the participants were familiar with the concept of smart cities and could mention specific application areas such as traffic or smart urban lighting. E5 extensively pondered both AI and smart cities, providing detailed analyses of their numerous challenges and opportunities, and reflecting on the environmental and economic connections. Nevertheless, almost all the rest were quite wary about the topic and considered it technocentric and dystopian. The City of Espoo has been promoting itself as a smart city (or a wise city), and perhaps not surprisingly, more participants living in Espoo were aware of smart cities and associated the concept with the digitalization of services. Importantly, the less the participant seemed to know about the phenomena under scrutiny, the more negative reactions it seemed to evoke: “These [AI and smart city] make me a bit afraid, or I feel horrified, like what is this, do we really need to have this.”

Our last example, nursing robots, was a more familiar topic for many. All the interviewees from both cities considered that a nursing robot could not replace human interaction, and some also expressed concerns about whether robots would be able to take care of them in a nursing home. Some were clearly appalled by the whole idea; however, those few participants who knew more about the topic considered that a nursing robot could be useful in some practical tasks, such as delivering food.

Overall, the digitalization of society raised concerns and strong opinions among the interviewees, and the number of digital devices and digital services was experienced as overwhelming by several individuals. V1 commented that “The more we get these (digital services), the more anxious I get.” Many interviewees in both cities raised concerns about the rapid pace of development and the vulnerability of the digital society; they were not assured that the digitalized society could withstand a major disruption or a catastrophe that could destroy its digital infrastructure. Although we can conclude that the broader implications and many societal dimensions of digitalization remained distant for our participants, they were interested in and quite eager to discuss digital technology and society.

Digital Connection as a Necessity

Most participants considered that digital technology helps save time and has made everyday life more flexible, as one can handle many things online, which is consistent with findings reported by Kainiemi et al. (2023). On the contrary, a few commented that their lack of digital skills makes taking care of everyday matters more time-consuming (V1, V5). On the other hand, online services also caused anxiety for some. For example, V2, V4, and E4 reported that they often spent a lot of time and felt lonely when searching for information from digital healthcare services or trying to understand reported medical information. V4 aptly summarized that “[ICT] has made it physically easier to take care of things but made it mentally more difficult.”

Most of our participants can be described as “basic users”, which refers to using digital technology for relatively simple tasks such as browsing the Internet, communication, or taking care of their matters through digital public services (cf. Warschauer & Matuchniak, 2010; Livingstone, 2003). However, one participant (E5) from Espoo was an exception. He can be described as an “advanced user,” as he utilized digital technology for more complex tasks, such as programming or developing software for academic research.

Everybody was engaging with the digital world to some extent, so we did not have any non-users. However, two participants (E1, E3) expressed a desire to quit using all digital technology if it were possible. However, they also felt that it is not an option in contemporary society. Many other participants also mentioned (e.g., V2, V5, E7) that staying digitally connected is a necessity in today’s world.

In both studied cities, leisure use was the most common engagement type, encompassing activities such as taking pictures, using social media, browsing the Internet, playing mobile games, listening to music, watching series online, reading online news, or conducting genealogy research online. The second most popular reason for using digital technology was economic, such as online banking or online shopping. Many participants used digital technologies for communication to stay in touch with family members and other social networks. In addition, two interviewees in Espoo (E2, E5) reported educational uses, such as attending Teams meetings or following research online. Furthermore, a few (E5, E7) were involved in online political or civic activities. Finally, all participants used digital public services. However, many expressed that they trust analogical services, such as paper forms, more when dealing with important personal matters, such as sharing health information or filling out documents related to taxation.

Current and Desired Forms of Digital Support

A significant number of our interviewees turned to their family or close friends for digital assistance. Previous research has acknowledged the significance of this kind of digital help (Hänninen et al., 2021). The problem with this approach appears to be that family members are not effectively teaching older adults; instead, they often do things for them. As a result, the older adults can lose their (digital) agency, and in the worst situation, this may lead to abuse as well as dependency. E6 described how a younger family member is offering help: “We sit next to each other, and they do everything. They do not teach. (...) I think that there is no benefit when they do not teach me.” On the other hand, receiving help from close ones can also fill social needs, which was evident in our data. It must also be considered that not everyone has such relationships.

Most of our interviewees primarily used digital technologies at home; however, none of them considered their homes a preferable place for receiving digital support from outsiders, mainly due to safety concerns. Half of the interviewees emphasized that the locations where public digital support is offered could include public spaces where they naturally spend time, such as libraries, cafés, grocery stores, or community centers. Older adult participants said they prefer face-to-face digital guidance where the counselor or teacher sees what is happening on the screen. This makes things easier, for example, if the digital vocabulary of an older adult is inadequate. One participant wanted to express a ‘utopia’, and envisioned that an ideal digital support would be offered in a “communal space. You would get peer support from others. And you could ask from the person sitting next to you, what is going on, and do we understand this in the same way. It would make learning more fun.”

When we presented the list of different digital support services already offered by the cities (Figure 3), many became confused: they had not even heard of most of the services, and it was unclear what kind of help different providers offer and for whom it is targeted. E7 said, “Now that I saw this list [of digital support services in Espoo], the first thing that came to my mind was, can’t they be somehow centralized? It seems a little strange that there are so many of these.” The interviewees suggested that the cities would inform older generations about digital support through conventional media, such as local newspapers, to raise awareness. Despite the seemingly long list of digital support services, several of our older adult participants and all three digital support providers we interviewed deemed that current services inadequately cater to the needs of senior citizens. For example, V1 needed help with a phone but had not got it: “I have tried to reach out to senior counselling in the library, but I couldn’t get an appointment. They said that they have no free time available. I do not know whom to turn to.” The volunteer from an NGO commented that “It [increased demand] is demonstrated by the fully booked appointments.” Some older adult participants had used commercial digital support services, such as those offered by teleoperators, but considered them expensive and ineffective.

Those few older adults who had reached public digital support providers had mixed experiences. V6 got assistance from the public library and described how library personnel had a very kind and professional approach. V5 had participated in an IT course but found it not very useful—she could not use her own device, and she felt that too much information was provided, which made the course difficult to follow. Interestingly, 8 of 14 interviewees from both cities explicitly emphasized the importance of involving the older population in developing municipal digital support together with the professionals. For example, E7 commented that “Those who have no idea about these digital devices should also be included.” E3 argued that the target group needs to be involved so that they can challenge and test the ideas. A couple of interviewees also underlined that, in addition to answering explicit, narrow questions, digital support should aim to help senior citizens more holistically. One participant emphasized the importance of proactive digital support over reactive approaches and suggested that instructors could recommend specific applications that would be beneficial to different individuals.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we present a case study exploring older adults’ experiences with digital technologies and the digitalization of public services, with the aim of producing knowledge that will assist the municipal sector in designing better public digital support services. The study was conducted in collaboration with the Cities of Espoo and Vantaa, located in the capital region of Finland, and drew on some background information from a previous public sector project, “Multi-sited digital support for city residents.” Below, we elaborate on our results and the entire study from a more comprehensive perspective, presenting three types of insights. We discuss, firstly, our choices related to the research approach and engagement with study participants; secondly, we reflect on the type of digital support that would generally serve older adults based on our findings; thirdly, we introduce more detailed design implications.

Adopting a Flexible and Responsive Research Approach

As explained in previous sections, we initially aimed to co-create better digital support services with older adults. However, our street-level interaction with individuals belonging to the group effectively demonstrated that we knew too little of their experiences and views related to digital technology, which led us to reassess our approach. We interpret that, due to their experiences of being marginalized by rapid technological development, they did not feel motivated to participate in addressing the issues of digital support. Methodologically, we transitioned from a PD-inspired approach to a design anthropological approach, in which people’s life-worlds are studied in-depth through ethnographic methods and their experiences are interpreted through a theoretical framework to open up new design horizons (Gunn et al., 2020; Smith & Otto, 2020; Ventura & Bichard, 2017). This way, we were able to respect older adults’ need to be heard but not to participate directly in solving issues they experienced as unjust.

An anthropological approach can effectively operate on multiple levels within a project (Dourish & Bell, 2011). It can reveal what is normally hidden and bring attention to the mundane. This is achieved by examining the underlying social and material forces that are involved in the problems we aim to address through design. It can offer an in-depth understanding of how people currently use technology, but it can also be focused on anticipating future developments and promoting change. Therefore, it can generate both implications for design, a collection of design guidelines relevant to specific circumstances, and assist in exploring entirely novel, prospective design possibilities. In other words, anthropological knowledge can be oriented towards different types of results. These different levels are exemplified in the following two subchapters.

From Digital Support to Holistic Digital Education

Our findings challenge the notion that multi-sited digital support services, designed to address the technical and operational issues of specific use cases, can effectively tackle the digital exclusion and digital literacy problems faced by the older population. Our interviews and other data highlighted that older adults are mostly basic users with poor self-efficacy, and with very fragmented digital literacy skills; some of them had good knowledge of specific devices, platforms, and applications they used actively, but even these individuals often seemed to lack a broader understanding of the role of digital technology in society. Learning incremental skills through short support sessions may help with smaller issues, but does not address the lack of comprehensive understanding, which can lead to fear, anxiety, and broader misunderstandings, as evident in our results. Ultimately, the lack of a more holistic understanding can lead to a loss of agency on multiple levels, as participation in society increasingly occurs through the Internet and digital venues. Non-use can occur when individuals lack a comprehensive understanding, leading to apprehension about making mistakes, concerns about cybercrime, and a general lack of confidence in their abilities. Numerous digital literacy and digital inequality scholars (for example, Iversen et al., 2018; Van Deursen et al., 2017; Toscano, 2011) argue that critical skills and understanding are focal for operating effectively in the digital realm and through digital technology.

Instead of focusing solely on digital support that addresses singular and narrow issues, more attention should be given to lifelong learning opportunities that target different dimensions of digital literacy, including those pertaining to critical literacy and broader critical understanding (Figure 1). Societies that strive for digitalization should offer public digital education targeted at older adults, structured in a manner that not only focuses on technical and operational skills, but also equips older persons with the ability to create and assess different kinds of content, and with a holistic understanding of various technological phenomena. In other words, we emphasize that merely educating people on how to create a PDF file or a social media profile and add content is insufficient; we also need education on what social media is and how it functions as part of society. Communicating on these issues does not necessarily have to be limited to one-way lectures; it could also occur through discussions or peer-to-peer debates. Facilitating conversations with older adults and experts regarding digital phenomena can bolster the self-confidence and self-efficacy of older people. Through this approach, older adults can voice their concerns about the weaknesses of digital society and gain a deeper understanding of the policies, strategies, and regulations implemented by nations and governments to protect their populations from such risks. It is essential to note that our participants were evidently open to discussing various technological phenomena, and everyone was keen to learn new skills, provided the methods and approaches suited their needs.

The study results highlighted that remote support or support taking place at home was not desirable. Following our study participants’ accounts on good digital support, we envision that from a spatial point of view, the learning opportunities could be offered in “learning cafés” or other public spaces that would act as points for face-to-face digital support and at the same time, offer possibilities for social interaction and peer support. The wide range of digital literacy skills was evident in our data, which supports the idea that older adults could also benefit from learning from each other.

Practical Design Implications

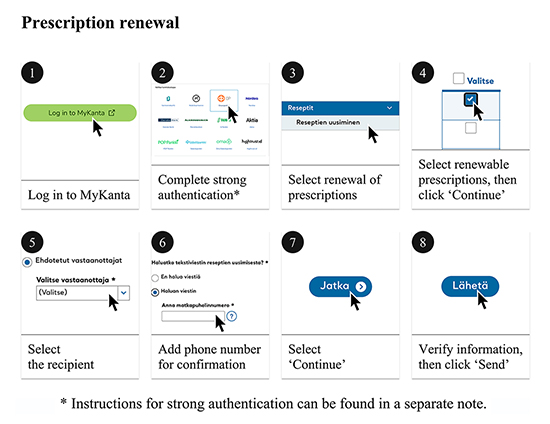

We can draw several more practical design implications from our study: some of the most prevalent examples are presented below. The first idea we present is primarily related to technical and operational skills: we suggest designing visual, step-by-step instructions for important matters. Studies indicate that older individuals require increased repetition to retain the knowledge and skills necessary for performing online tasks. This finding is consistent with the research conducted by Korjonen-Kuusipuro et al. (2021), which suggests that older individuals may require additional time and effort to acquire new skills. To promote the digital literacy of older individuals and empower them to acquire knowledge autonomously, digital support services could offer detailed and sequential guidance on how to perform specific tasks within digital platforms. These instructions enable older citizens to independently practice and participate at home, thereby enhancing their digital abilities and self-reliance. The choice of assigned tasks should be based on research into the typical internet activities carried out by older citizens, such as implementing robust authentication measures in banking services, communicating with healthcare providers, refilling medical prescriptions, and scheduling doctor appointments. This practical suggestion is partly inspired by the visual aids we used in the interviews, as they worked very well (Figure 5). presents an example of such step-by-step instructions for renewing prescriptions in digital service OmaKanta.

Figure 5. Example for a card with prescription renewal instructions.

The second idea could be operationalized by educating older adults on any dimension of digital literacy, such as the use of plain language. Interviews indicated that senior individuals derive significant benefits from patient digital service providers who communicate calmly and use simple language, rather than sophisticated technological terminology. Promoting the use of simple language in marketing efforts can also help challenge the assumptions and biases that older individuals may have towards digital support services. These biases may include the belief that such services are intended only for “serious” digital issues or that they are primarily designed for young people who are proficient in using complex terminology. By prioritizing the use of simple and clear language in communication techniques, digital support can become more attractive and accessible to residents aged 65 and above. According to Korjonen-Kuusipuro et al. (2022), old age is often accompanied by both physical and cognitive impairments. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the educational needs of individuals with memory disorders.

Finally, the last practical idea is directly connected to digital support: we have seen that there is a serious problem with how the Cities of Espoo and Vantaa communicate their digital support services. Problems are arising from a lack of communication, especially for older adults who need to be informed about the variety of services available. As a result, these services need to be promoted and made more widely known. Thus, this study argues that disseminating information about municipal digital support services at actual sites where senior citizens conduct their errands could be a useful communication strategy. Additionally, information should be disseminated through media that older citizens follow, such as local newspapers.

Limitations and Future Studies

The clearest limitation of our study is its relatively short timeframe, as it was finalized within five months. It focuses on providing background information and initial design ideas to enhance digital support for older adults, but implementation strategies and putting the ideas into practice fall largely outside the scope of the paper. However, at the time of writing this paper, we are planning new collaboration activities with the Cities of the capital region of Finland with the goal of mitigating digital inequalities.

Furthermore, it is essential to recognize that there are several subgroups within the population of adults aged 65 and above. The interviewed older residents in Vantaa and Espoo did not have significant mobility limitations, thus they were able to seek help in public libraries and other public spaces. However, older adults who are unable to visit public spaces independently must have access to alternative avenues of communication. These groupings should be proactively identified by Vantaa and Espoo, who should then create tailored digital support and digital education strategies in accordance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland project “Digital Inequality in Smart Cities” (DISC, 332143). We would like to express our gratitude to our interviewees and our collaborators in the Cities of Espoo and Vantaa.

References

- Björgvinsson, E., Ehn, P., & Hillgren, P.-A. (2010). Participatory design and “democratizing innovation.” In Proceedings of the 11th biennial participatory design conference (pp. 41-50). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1900441.1900448

- Björgvinsson, E., Ehn, P., & Hillgren, P.-A. (2012). Design things and design thinking: Contemporary participatory design challenges. Design Issues, 28(3), 101-116. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00165

- Björgvinsson, J., & Karasti, H. (2012). Ethnography: Positioning ethnography within participatory design. In J. Simonsen & T. Robertson (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of participatory design (pp. 86-116). Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203108543

- Blank, G., & Groselj, D. (2016). Dimensions of Internet use: Amount, variety, and types. Information, Communication & Society, 17(4), 417-435. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.889189

- Broos, A., & Roe, K. (2006). The digital divide in the playstation generation: Self-efficacy, locus of control and ICT adoption among adolescents. Poetics, 34(4-5), 306-317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2006.05.002

- Christensen, C., Ehrenberg, N., Christiansson, J., Grönvall, E., Saad-Sulonen, J., & Keinonen, T. (2022). Volunteer-based IT helpdesks as ambiguous quasi-public services - A case study from two Nordic countries. In Proceedings of the Nordic human-computer interaction conference (Article No. 44). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3546155.3546660

- City of Espoo. (2021). Espoo-tarina [The story of Espoo]. https://www.espoo.fi/fi/kaupunki-ja-paatoksenteko/espoo-tarina

- City of Vantaa. (2021). Innovaatioiden Vantaa: Kaupunkistrategia 2022-2025 [The Vantaa of Innovations: City Strategy 2022–2025]. https://www.vantaa.fi/en/city-and-decision-making/economy-and-strategy/city-strategy-vantaa-innovations

- Comi, A., Bischof, N., & J. Eppler, M. (2014). Beyond projection: Using collaborative visualization to conduct qualitative interviews. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 9(2), 110-133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/QROM-05-2012-1074

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- Desai, S., McGrath, C., McNeil, H., Sveistrup, H., McMurray, J., & Astell, A. (2022). Experiential value of technologies: A qualitative study with older adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), Article 2235. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042235

- Design Council. (2013). Design for public good. Design Council. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/fileadmin/uploads/dc/Documents/Design%2520for%2520Public%2520Good.pdf

- Dourish, P., & Bell, G. (2011). Divining a digital future: Mess and mythology in ubiquitous computing. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262015554.001.0001

- Emejulu, A., & McGregor, C. (2019). Towards a radical digital citizenship in digital education. Critical Studies in Education, 60(1), 131-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1234494

- Erstad, O. (2015). Educating the digital generation-exploring media literacy for the 21st century. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 10(Jubileumsnummer), 85-102. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2015-Jubileumsnummer-07

- Eshet, Y. (2004). Digital literacy: A conceptual framework for survival skills in the digital era. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 13(1), 93-106.

- Espoo Esbo, & Vantaa. (2023). Digituki–Arkea ja yhdenvertaisuutta. [Digital Support – Everyday Life and Equality]. https://www.vantaa.fi/sites/default/files/document/Digituki%20-%20arkea%20ja%20yhdenvertaisuutta%20raportti.pdf

- Eurostat. (2022). Statistics explained. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Main_Page

- Gecas, V. (1989). The social psychology of self-efficacy. Annual Review of Sociology, 15(1), 291-316. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.15.080189.001451

- Gunn, W., Otto, T., & Smith, R. C. (2020). Design anthropology: Theory and practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003085195

- Gustafsson, M., & Wihlborg, E. (2021). ‘It is unbelievable how many come to us’: A study on community librarians’ perspectives on digital inclusion in Sweden. The Journal of Community Informatics, 17, 26-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.15353/joci.v17i.3490

- Győrffy, Z., Boros, J., Döbrössy, B., & Girasek, E. (2023). Older adults in the digital health era: Insights on the digital health related knowledge, habits and attitudes of the 65 year and older population. BMC Geriatrics, 23(1), Article 779. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04437-5

- Hänninen, R., Taipale, S., & Luostari, R. (2021). Exploring heterogeneous ICT use among older adults: The warm experts’ perspective. New Media & Society, 23(6), 1584-1601. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820917353

- Helsper, E. (2015). Inequalities in digital literacy: Definitions, measurements, explanations and policy implications. LSE Research Online. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/68329/1/Helsper_Inequalities%20in%20digital.pdf

- Helsper, E. (2019). Why location-based studies offer new opportunities for a better understanding of socio-digital inequalities? LSE Research Online. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/102262/1/Helsper_Why_location_based_studies_offer_opportunities_2019.pdf

- Helsper, E. (2021). The digital disconnect: The social causes and consequences of digital inequalities. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526492982

- Helsper, E. J., & Eynon, R. (2013). Distinct skill pathways to digital engagement. European Journal of Communication, 28(6), 696-713. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323113499113

- Helsper, E. J., & Smahel, D. (2020). Excessive internet use by young Europeans: Psychological vulnerability and digital literacy? Information, Communication & Society, 23(9), 1255-1273. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1563203

- Heponiemi, T., Gluschkoff, K., Leemann, L., Manderbacka, K., Aalto, A.-M., & Hyppönen, H. (2023). Digital inequality in Finland: Access, skills and attitudes as social impact mediators. New Media & Society, 25(9), 2475-2491. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211023007

- Hinrichsen, J., & Coombs, A. (2013). The five resources of critical digital literacy: A framework for curriculum integration. Research in Learning Technology, 21, Article 21334. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v21.21334

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hyysalo, S., Hyysalo, V., & Hakkarainen, L. (2019). The work of democratized design in setting-up a hosted citizen-designer community. International Journal of Design, 13(1), 69-82. https://doi.org/10.57698/v13i1.05