Destination Unknown: Navigating the Messy Journey of Design-Enabling Transformation in Public Organizations

Geert Brinkman 1,*, Arwin van Buuren 1, and Mieke van der Bijl-Brouwer 2

1 Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

2 Independent Researcher, Delft, The Netherlands

Public organizations around the world are increasingly investing in their creative-purposive design capabilities. However, they often face difficulties in doing so and come to realize that this implies a fundamental organizational transformation. To date, knowledge about how such a transformation is realized remains limited. In this study, we conducted four focus groups and an in-depth case study of a Dutch municipality to explore how such a transformation comes about and how it can be fostered. We adopted a complexity perspective on organizational transformation, which enabled us to (1) gain a better understanding of how transformation unfolds in the complex reality of a public organization, (2) reveal how transformative work is continuously refined, and (3) how the engagement of public organizations with creative-purposive design evolves. Accordingly, this study contributes to both theory and practice of design-enabling transformation of public organizations.

Keywords – Public Sector Design, Design-Enabling Organizational Transformation, Complex Adaptive Systems.

Relevance to Design Practice – This study enhances our understanding of how design-enabling transformation unfolds in public organizations and how it can be fostered.

Citation: Brinkman, G., van Buuren, A., & van der Bijl-Brouwer, M. (2025). Destination unknown: Navigating the messy journey of design-enabling transformation in public organizations. International Journal of Design, 19(3), 101-119. https://doi.org/10.57698/v19i3.05

Received May 31, 2024; Accepted July 21, 2025; Published December 31, 2025.

Copyright: © 2025 Brinkman, van Buuren, & van der Bijl-Brouwer. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-access and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: brinkman@essb.eur.nl

Geert Brinkman is a Ph. D. candidate at the Erasmus Social Design Hub and Govlab010 as part of the Department of Public Administration and Sociology at Erasmus University Rotterdam. Geert works at the intersection of design and public administration, advancing both the practice and governance of public sector design.

Arwin van Buuren is a professor of Public Administration at Erasmus University Rotterdam and the academic director of the Erasmus Social Design Hub. His research interests are on issues of (co-)design for policy and governance, invitational governance and self-organization, collaborative governance and co-creation, policy innovation, and institutional change.

Mieke van der Bijl-Brouwer is an independent researcher, teacher, and speaker. Her expertise and interests include design theory and practices for complex societal challenges, systemic design, and transdisciplinary practices and education. Mieke has worked in various research, design, and education roles across the Netherlands and Australia. Mieke is an adjunct fellow at the Transdisciplinary School at the University of Technology Sydney. She holds a Master of Science in Industrial Design Engineering from Delft University of Technology and a Ph. D. in user-centered design from the University of Twente, the Netherlands.

Introduction

Design is a core activity of public organizations. After all, public organizations are responsible for designing institutions, strategies, policies, and services for the common good. However, this does not imply that they are equipped with the necessary design capabilities to adequately perform their design tasks.

The literature on design in the field of public administration highlights that design in most (Western) public organizations is grounded in a rational-instrumental tradition (Crosby et al., 2017; Clarke & Craft, 2018; Turnbull, 2018). Rational in the sense that the use of logical, systematic, and objective methods is emphasized (Hermus et al., 2020). Instrumental in the sense that it revolves around identifying the most efficient and effective means to achieve certain predefined goals (Howlett, 2019). Design, as such, is essentially a knowledge-driven, evidence-based, expert-led, and solution-oriented endeavor (Enserink et al., 2013), often characterized as orderly and mechanical (Head, 2010). Public organizations have a long history of carrying out their design tasks in this manner and have become increasingly adept at doing so (Head & Alford, 2015). This is reflected in the high degrees of hierarchy, departmentalization, formalization, standardization, and specialization that are often found in public organizations (Joosse & Teisman, 2021). Rational-instrumental design thus has become a “design legacy” (Junginger, 2014, p. 165) in public organizations.

While rational-instrumental design is suitable for performing well-defined design tasks—i.e., design tasks that are clear, structured, and finite, such as building a bridge or improving waste management—it is not fit for purpose for ill-defined design tasks—i.e., design tasks that are ambiguous, complex, and open-ended, such as reducing social inequality or tackling climate change (Head, 2022). Given that many of the design tasks of public organizations fall into the ill-defined category, it is quite problematic that they mainly possess rational-instrumental design capabilities. As societal crises and public distrust continue to escalate, there is an urgent need to expand the design repertoire of public organizations (Crosby et al., 2017; Turnbull, 2018).

Consequently, “new” design approaches such as design thinking, service design, social design, and systemic design have gained considerable traction in the public sector (Bason, 2014; Junginger, 2017; van Buuren et al., 2023). While these approaches differ in their principles, practices, and processes, their underlying logic is very much alike. This logic is best described as creative-purposive. Creative in the sense that the use of imagination, speculation, and intuition is emphasized (Lewis et al., 2020). Purposive in the sense that it revolves around identifying the values at stake, and coming up with a suitable means to realize these (Sanders & Stappers, 2008). Design, as such, is primarily inspiration-driven, empathy-based, citizen-led, outcome-oriented (Hermus et al., 2020), and exploratory and provisional (Kimbell & Bailey, 2017). As such, it is deemed well-suited for ill-defined design tasks (von Thienen et al., 2014). Creative-purposive design is thus considered a valuable expansion of the rational-instrumental design repertoire of public organizations (Blomkamp, 2018; Mintrom & Luetjens, 2016).

For this reason, public organizations worldwide are increasingly seeking to enhance their creative-purposive design capabilities (Kang, 2021; Kim, 2023; Malmberg, 2017). However, this has proven far from easy. Accommodating creative-purposive design in a context that is geared towards rational-instrumental design presents significant challenges (Kimbell & Bailey, 2017; Lewis, 2021; Pirinen et al., 2022); words such as “near-allergic reactions” (Schaminee, 2018, p. 51) and “tissue incompatibility” (Boztepe et al., 2023, p. 3) aptly describe their mismatch. Creative-purposive design is often disregarded as being too subjective, freewheeling, and playful (Rauth et al., 2014). Moreover, the hierarchical, formal, and siloed organizational environment that most public organizations offer starkly contrasts the horizontal, informal, and collaborative organizational environment needed for creative-purposive approaches to thrive (Brinkman et al., 2023). Accordingly, it is increasingly recognized that the development of creative-purposive design capabilities requires a fundamental organizational transformation (Bason & Austin, 2021; Deserti & Rizzo, 2015; Junginger, 2017), or, as Lewis (2021) put it, a “tilting of whole systems toward new ways of working” (p. 250).

While there are quite a few ideas about how a creative-purposive design-enabling organizational transformation can be fostered, empirical studies on how such a transformation is realized are limited. Most studies focus on the barriers, challenges, and tensions of transformation instead (Boztepe et al., 2023; Pirinen et al., 2022; Starostka et al., 2022). Recent calls for papers on design-led policy and governance (Mortati et al., 2022) and design in and for the public sector (Boztepe et al., 2024) underline the need for a better understanding of organizational transformation. In this study, we use a complexity perspective to shed light on this phenomenon. We conducted four focus groups and an in-depth case study of a Dutch municipality that set on a path towards a citizen-centered civil service through creative-purposive design nine years ago. Based on this, we demonstrate (1) how design-enabling transformation unfolds in the complex reality of a public organization, (2) how the transformative work to foster such a transformation is continuously adapted and evolving, and (3) how, over time, the engagement of public organizations with creative-purposive design evolves.

Literature Review

Although design has been a topic of interest in public administration since the 1950s, most studies on design capabilities and design-enabling organizational transformation originate from the field of design itself. These studies often center on creative-purposive design, thereby overlooking rational-instrumental design. In the following section, we will discuss these creative-purposive centered studies, but we will do so from a pluralistic perspective on design.

Developing Creative-Purposive Design Capabilities as Organizational Transformation

As is done in many other studies (e.g., Kang, 2021; Kim, 2023; Starostka et al., 2022; Yeo et al., 2023), we will take Malmberg’s work as a starting point for defining design capabilities. Malmberg (2017) defines design capabilities as an organization’s ability to effectively carry out its design tasks, and identifies three interrelated dimensions that together determine design capabilities: awareness, resources, and structures. Awareness relates to the organization’s understanding of when what kind of design approach may be fit for purpose. Resources concern the organization’s access to relevant design expertise to carry out its design tasks. Structures refer to the organization’s administrative systems that are put in place to enable design. However, as Elsbach and Stigliani (2018) explain, an organization’s shared beliefs, norms, and values about what is the “right way” to design also shape the way in which an organization carries out its design tasks. Design capabilities are thus also determined by a fourth dimension: culture.

If we take the position that an organization’s design capabilities are determined by the dimensions of awareness, resources, structures, and culture, developing design capabilities essentially involves efforts to change the organization along (some of) these dimensions. Given that most public organizations are geared towards rational-instrumental design, it can be assumed that enhancing their creative-purposive design capabilities requires change along all four dimensions. Hence, it involves a fundamental organizational transformation (Bason & Austin, 2021; Deserti & Rizzo, 2015; Lewis, 2021).

Mechanisms and Approaches for Fostering Organizational Transformation

Existing literature identifies several mechanisms and corresponding approaches to foster such a transformation. We will list these mechanisms and approaches below, without claiming to be exhaustive:

- Competence building: Several authors suggest that competence building can foster organizational transformation (e.g., Holmlid & Malmberg, 2018; Malmberg, 2017). In practice, this often involves workshops, training, or more expansive learning trajectories alongside projects, typically led by an expert designer.

- Knowledge dissemination: Others propose that knowledge dissemination could promote design-enabling transformation (e.g., Kang & Prendiville, 2018; Lima & Sangiorgi, 2018; Malmberg & Wetter-Edman, 2016). This typically involves “packaging” creative-purposive design knowledge through design frameworks, process models, and toolkits to enhance its uptake. Dissemination is usually achieved by appointing creative-purposive design champions, ambassadors, or catalysts who translate and promote the knowledge across the organization (Starostka et al., 2023).

- Experimental sandboxing: Experimental sandboxing is also often mentioned as a helpful mechanism to prompt organizational transformation (Deserti & Rizzo, 2015; Meijer-Wassenaar & Bakker-Joosse, 2023; Starostka et al., 2024). This entails setting up a “dedicated safe space” (Carstensen & Bason, 2012, p. 5) for creative-purposive design, such as a public sector innovation lab (McGann et al., 2018). These labs serve as “administrative bypasses” to enable, promote, and gain experience with creative-purposive design.

- Network building: Another mechanism for fostering organizational transformation is network building (Holmlid & Malmberg, 2018; Kim, 2023; Terry, 2012). Practitioners often establish communities of practice to exchange experiences, learn from one another, enhance their visibility, collaborate, and draw in additional members.

- Institutioning: Finally, institutioning is often regarded as a mechanism to cultivate design-enabling transformation (Brinkman et al., 2023; Karpen et al., 2022; Kim, 2023). Vink and Koskela-Huotari (2022) describe how creative-purposive design itself fosters reflexivity, thereby contributing to institutional change. In addition, Rauth et al. (2014) and Kim (2023) show how institutional change can be realized through the pragmatic, moral, and cognitive legitimization of creative-purposive design.

As can be seen, there are several ideas about how a design-enabling transformation of public organizations can be fostered. Still, in practice, there are considerable pitfalls and challenges.

Pitfalls and Challenges of Organizational Transformation

Numerous authors have identified the challenges, tensions, and frictions that transformative work brings about (e.g., Boztepe et al., 2023; Pirinen et al., 2022; Starostka et al., 2022). These relate to the transformative work itself, as well as the context within which it is undertaken.

As Junginger (2014) notes, most transformative work is based on the misguided assumption that public organizations are void of design. The design expertise that is already present in public organizations is thus disregarded entirely. From this point of departure, transformative work is not only often met with resistance, but it also eliminates the possibility of seeking synergies with established design capabilities. Moreover, many of the above-mentioned approaches to foster transformation also have their shortcomings. Public sector innovation labs, for example, tend to become isolated, ending up as “islands for experimentation” (Tõnurist et al., 2017, p. 1462), thereby having little impact on the rest of the organization (Lewis et al., 2020). Similarly, while experiential learning trajectories enable a select group of people to design in a creative-purposive manner, they often do not enable these individuals to apply what they have learned in future projects or disseminate their knowledge across the organization (Holmlid & Malmberg, 2018). These examples highlight how transformative work is often flawed and mainly leads to changes along the awareness and resources dimensions, but does not result in deeper-level change along the dimensions of structures and culture (e.g., Brinkman et al., 2023; Malmberg, 2017; Kim et al., 2022).

This, however, also relates to the often unfavorable conditions for transformation in the public sector. Organizational transformation is a gradual, long-term process that requires persistent and sustained effort (Bailey, 2012). Accordingly, it involves making considerable investments (e.g., time, money, personnel), which are generally difficult to obtain, given that acute crises and pressing demands from citizens and politicians call for immediate action and instant delivery (McGann et al., 2021). Sustaining continuity is further complicated due to the high turnover rates in public organizations (Kang & Prendiville, 2018). Moreover, the siloed structure of public organizations hinders transformation across their different divisions and departments (Pirinen et al., 2022). In addition, the risk-averse culture often found in public organizations is commonly perceived as an impeding factor (Mulgan & Albury, 2003). Transformation also implies challenging and changing institutionalized rules, norms, values, and assumptions, which are notoriously resistant to change (Karpen et al., 2022). Lastly, it often involves shifting power dynamics, which can make leaders reluctant to facilitate and embrace transformation (Starostka et al., 2022).

These observations underscore the need to adapt transformative work to the complex environment in which it occurs (Werkman, 2009), suggesting that a complexity perspective on organizational transformation may be valuable.

A Complexity Perspective on Organizational Transformation

A complexity perspective on organizational transformation is gradually gaining traction in the organizational sciences, as a response to the rising criticisms that existing approaches and models of organizational transformation insufficiently reflect the messy reality of organizations (By, 2005; Burnes, 2005). This perspective is based on the idea that organizations are complex adaptive systems (Grobman, 2005)—i.e., they are networks of local interactions between individuals (Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2001). From these local interactions, collective patterns and behaviors emerge that are different from the local ones (McDaniel, 2007). In these local interactions, individuals learn and adapt in response to one another as well as to environmental influences (Stacey, 1995). This means that these interactions are continuously evolving, and so are the emergent collective dynamics (Schneider & Somers, 2006). Such evolution is both non-linear and path-dependent, as learning and adaptation occur spontaneously but are also institutionally conditioned (David, 1994). From this perspective, transformative work thus essentially involves local interactions that continuously evolve through spontaneous and conditioned learning and adaptation. Transformation unfolds as an emergent and evolving outcome of these interactions.

To date, there are very few empirical studies that adopt a complexity perspective on transformation (Riaz et al., 2023), particularly those focusing on public organizations (Kuipers et al., 2014). Our understanding of the complex dynamics of transformation and transformative work is thus limited. Therefore, we aim to answer the following three research questions:

RQ1. How does transformation unfold in the complex reality of a public organization?

RQ2. How is transformative work continuously adapted, and how does it evolve?

RQ3. How does the engagement of public organizations with creative-purposive design evolve?

Methods

In this study, we took a two-step mixed-methods approach. First, we conducted four focus groups with practitioners engaged in transformative work. Second, we conducted an in-depth study of a Dutch municipality that embarked on a design-enabling transformation journey nine years ago.

Focus Group Design

The focus groups aimed to gain a broad overall understanding of the transformative work that practitioners engage in and how this work impacts the way public organizations engage with creative-purposive design—i.e., to find answers to RQ2 and RQ3. We also used the focus groups to identify relevant topics for a more in-depth investigation.

Sampling

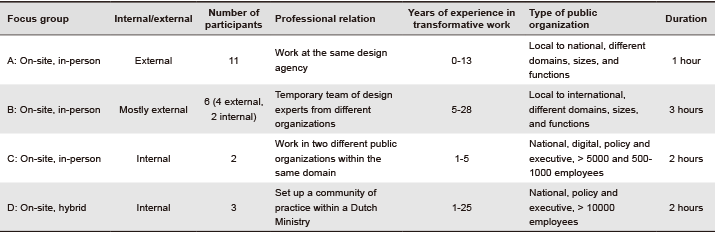

In practice, transformative work is carried out by professionals working both within and outside public organizations. We aimed to capture both perspectives and therefore conducted two focus groups with primarily external professionals and two focus groups with internal professionals. Differences in region, domain, size, and function of public organizations matter when engaging in transformative work. We wanted to cover this variety and selected participants accordingly. All participants, however, were mainly working with(in) Dutch public organizations. Moreover, the participants in each group were in one way or another professionally related. This was to ensure that the participants felt comfortable sharing their perspectives, could relate to one another’s experiences, and spoke the same language (Kleiber, 2003).

Setting

The first author of this article moderated the focus groups. Moderation primarily involved keeping the conversation on topic while ensuring that it was well-balanced and that everybody’s voice was heard (Morgan, 1996). The aim was to conduct all focus groups on-site and in-person in order to facilitate moderation and productive dialogue. Hence, in each case, a location was chosen that was deemed most convenient for the participants. In Focus Group D, one participant was unable to attend in person, so the focus group was converted into a hybrid format. The duration of the focus groups varied, depending on the participants’ availability.

Table 1. The sampling and setup of each focus group.

Data Gathering

All focus groups were audio recorded. Visual prompts were used to probe for experiences, structure the conversation, and generate ideas (Breen, 2006). This included a taxonomy of strategies to make way for creative-purposive design approaches (see Brinkman et al., 2023), a Theory of Change logic model, timelines, and the Public Sector Design Ladder (Design Council, 2013)—see Appendix A. Participants were asked to map out their transformative efforts on the frameworks that were used. In Focus Group A, we used the taxonomy to inventorize different approaches to transformation. In turn, in Focus Group B, we developed a Theory of Change logic model to discuss how transformative work cumulatively contributes to transformation as a logical chain of progressive and interrelated actions. Next, in Focus Group C, we utilized the timeline and Public Sector Design Ladder to map the evolution of transformative work over time and across different levels of design maturity. In Focus Group D, it was decided not to use any prompts as this made the conversation difficult to follow for the participant who called in from home. In this case, the participants were asked to introduce themselves by sharing their personal transformative journey related to their transformative work, which served as a starting point for further dialogue. In each focus group, participants were asked for details on their transformative work and how this led to changes in the engagement with creative-purposive design of the public organizations that they worked with(in)—e.g., what were the opportunities, barriers, challenges, and lessons learned, how this shaped their transformative work, and what kind of changes they had achieved. As can be seen, our approach differed in each of the focus groups. Based on the insights gained in each focus group, we adapted our means to gather data. Accordingly, our approach also evolved.

In-Depth Case Study Design

The case study aimed to gain a more in-depth understanding of how design-enabling transformation comes about in the complex reality of a public organization, and particularly how both transformative work and the organization’s engagement with creative-purposive design evolve over time—i.e., to address all RQs.

Case Selection

We purposefully selected the municipality (with over 9,000 employees) of one of the top 5 largest cities in the Netherlands as a “single significant case” (Patton, 2015, p. 266). This municipality embarked on a journey of design-enabling transformation nine years ago. Along the way, it has established creative-purposive design leadership positions (from management to director level) and developed a solid creative-purposive design practice with over 35 full-time design researchers, service designers, UX designers, and social designers working in two different departments. Over the years, it has established an extensive track record of completed projects within the municipality’s various departments, and is currently running interdepartmental programs as well.

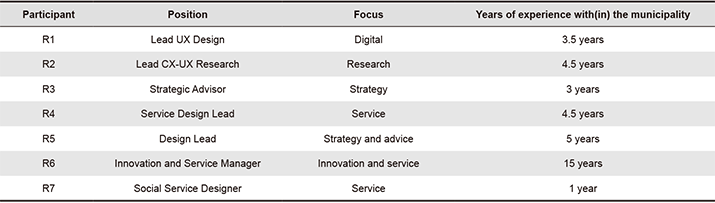

Participant Selection

Participants were selected in close collaboration with one of the in-house designers who has been part of and involved in the transformation that the municipality has undergone in the past nine years. The in-house designer introduced the first author to six other colleagues who have played a crucial role in this transformation; see Table 2 below for an overview.

Table 2. An overview of the participants in this case study.

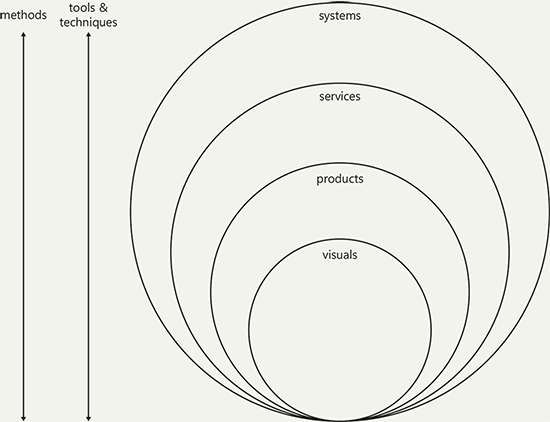

Data Gathering

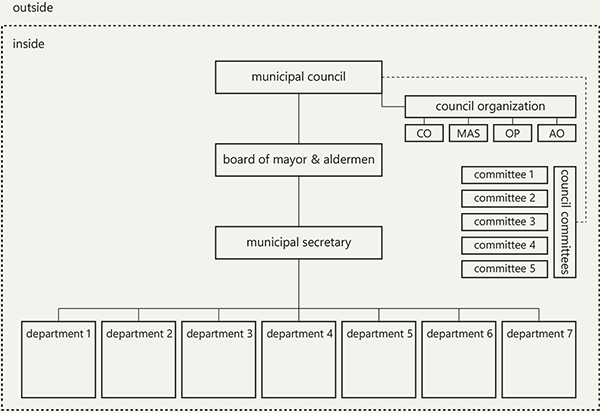

Five videos and an internal document were shared with the first author to provide background information, which was used as support material for the interviews. The first author conducted all seven semi-structured interviews, following the guidelines outlined by Galletta (2013). According to what was deemed most convenient for the participants, two interviews were conducted in person, and five interviews were conducted online using Microsoft Teams. The interviews lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. Again, visual prompts were used to probe for experiences (printed for the in-person interviews, and Miro for the online interviews). The prompts that were used were different from those in the focus groups (see Appendix B). An onion model of the four orders of design (based on Buchanan, 2001) was employed to gain a deeper understanding of the types of “products” designed, the creative-purposive design approaches used for this purpose, and how these have evolved over time. An organizational chart of the municipality was used to map out where creative-purposive design expertise, mindsets, and sponsors were located within and outside the organization. A framework of design maturity (based on Brinkman & Kim, 2024) was used to indicate how the organization’s level of design maturity has changed. Finally, a timeline was used to develop a chronological story of the organization’s transformative journey.

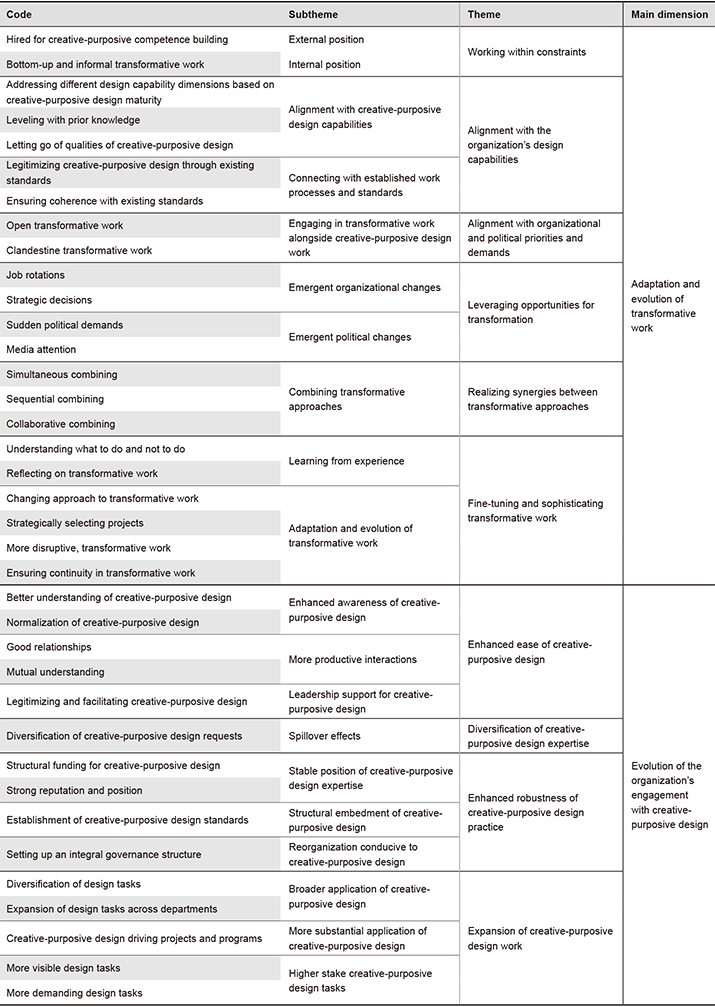

Data Analysis

Both the focus groups and interviews were transcribed in full and thematically analyzed. The analysis was conducted in three rounds, each involving a recursive process of coding, theme generation, thematic mapping, reviewing, and refinement (Braun & Clarke, 2006). In the first round, the focus groups were analyzed. This was followed by an analysis of the in-depth case study. For the third and final round, both analyses were integrated to enhance the robustness of our findings. Themes from the literature review—i.e., the dimensions of design capabilities, the mechanisms and approaches to transformative work, the pitfalls and challenges of transformation, and the complex dynamics of interactive learning, adaptation, evolution, and emergence - were used to guide the analysis (Bowen, 2006). In each round, these themes were further refined and complemented. Finally, these were checked for internal homogeneity, external heterogeneity, and coherence with the data (Patton, 2015). The coding tree that resulted from this can be found in Appendix C. In the next two sections, we will present our findings and illustrate these with representative quotes.

Findings

Below, we will offer a “thick description” (Ponterotto, 2006, p. 538) of the transformative journey that the municipality underwent. In our view, a thick description is a suitable way to vividly portray how transformation unfolds in the complex reality of a public organization. This section primarily addresses RQ1, but also offers important insights regarding RQ2 and RQ3, which will be discussed in the analysis section that follows.

The Messy Journey of Design-Enabling Organizational Transformation

Chapter 1: Embarking on a Path Towards a Citizen-Centered Civil Service

Nine years ago, a group of civil servants was tasked with developing a municipality-wide vision for service delivery. This turned out to be challenging, mainly because working across sectors is not part of the municipality’s DNA: “in a bureaucracy you have a very compartmentalized and extensive division of responsibilities” (R6), so “the average civil servant’s worldview is heavily linked to their organizational responsibility” (R6). The resulting vision was essentially a compilation of the various departmental visions, “stitched together” (R6). Still, a core spearhead of the vision was “improving services from the lifeworld of the citizen” (R6).

Yet, because the municipality’s service delivery was “politically not deemed very interesting” (R6), “no additional funds were allocated for the implementation of this vision” (R6). The civil servants thus decided to lobby for investment funds from each department. However, given the compartmentalized mindsets, this led to “fundamental discussions about: who pays and who benefits” (R6). Ultimately, it took “a lot of memos” (R6) and “about two years of going back and forth” (R6) before the different departments chipped in to implement the vision, which, in the meantime, had remained exactly the same: “This decision could have been made in one or two meetings [...] But then it still gets stuck for two years, because of these organizational obstacles” (R6).

Chapter 2: Gaining Traction

The civil servants began “setting up the building blocks to realize the vision” (R6). In their view, improving services from the lifeworld of the citizen required “insights about the lives of citizens, and also insights about how the different municipality’s services are experienced” (R6). Accordingly, they established the Town Room, a space where citizens and civil servants come together to discuss the citizens’ needs and experiences regarding the municipality’s services. This was quite a success; it revealed a strong demand for the research that was conducted in the Town Room, as well as a need to complement this research with more “design-like approaches” (R6) to “come up with ideas about how services can be improved” (R6). Hence, they decided to establish a municipality-wide design team (Team ID) and hire a UX researcher and a service designer.

At this point, the initial investment funds were running low, and there was limited “willingness to invest more” (R6). Having learned from their past experiences, the civil servants knew that it was “impossible to get this organized from the top down” (R6), so they decided to “come up with a trick” (R6) that enabled them to “keep building from the bottom up” (R6); they started to sell their expertise within the organization. With a good dose of “marketing” (R4) and “bluff poker” (R4), Team ID gained considerable traction. It successfully sold a large number of projects and secured a substantial amount of resources, which were reinvested in further expanding the team.

Interestingly, these bottom-up developments were possible because the position of general manager was left vacant for two years, enabling the team to “basically do whatever we wanted” (R4).

Chapter 3: Building a Track Record

As Team ID gained experience in conducting projects across various domains (e.g., streamlining the process for permit applications, providing citizen-centered debt assistance, enhancing library services, and improving communication about sustainability), it continued to face challenges in getting its solution proposals adopted and implemented. The team did very “enriching advisory work” (R5), but very little “implementation of this advice” (R5), because of a “clash of logics between design and implementation” (R5). Often, “it seemed like we were on the same page, but then it turned out we were not” (R2). Accordingly, the team shifted its approach, conducting “almost every step in co-creation with our colleagues from the other departments” (R2), “to make sure that it [the design] gets implemented” (R2). This enabled the team to showcase more realized examples and “evidence our impact” (R6), and, accordingly, build a stronger case for its work and generate even more demand for its expertise.

Chapter 4: Securing a More Strategic Position and Becoming More Strategic

At a certain point, Team ID reached the limits of what it could achieve from the bottom up. It was working with over 20 full-time employees (e.g., UX researchers, UX designers, service designers, and social designers), but still running on incidental project funding. The “business risk became too big” (R6). The team had to secure structural funding, and thus a more strategic position. Fortunately, by this time, a new general director had been appointed to lead the team’s department. Team ID seized this opportunity by proclaiming the general director as the municipality-wide Chief Customer Officer (CCO). While initially, “he didn’t understand why this was his job” (R4), after “a lot of talking” (R4), “he eventually got it” (R4). Accordingly, the CCO began advocating for citizen-centered municipal services in higher places within the organization. This enhanced the team’s visibility and enabled it to reach directors of other departments and obtain additional resources more easily.

Meanwhile, the publication of a national research report revealed “somewhat embarrassing outcomes” (R5) of the municipality’s business climate. Accordingly, the municipal council decided to establish a program to enhance the municipality’s services for entrepreneurs. Recognizing the opportunity that this offered, Team ID reached out to the policy advisor who was responsible for the program. Since they had previously worked together, the policy advisor agreed to involve the team. Initially, Team ID was asked to “play an advisory role” (R4), which gradually shifted to a more “steering role” (R4), and eventually, the team adopted the entire program.

Chapter 5: Transformation as a Secondary Primary Objective

The program was by no means easy to get off the ground. While having a CCO helped, setting up a cross-departmental program involving four directors from different departments was difficult. Integrating the different sectoral goals into a shared vision, establishing the governance for it, and obtaining integral funding proved challenging; the team was “not familiar with the entire governance of this” (R4), and “the organization has no clear structures for this” (R4) either. Additionally, Team ID identified a fundamental organizational challenge in realizing the program. However, it was “not allowed to make it about reorganization” (R4). After eleven revisions, and with half of the budget that Team ID initially aimed for, the program was launched. While its primary aim is to improve the entire portfolio of the municipality’s services, it also includes secondary transformative goals, such as “developing the organizational capability to continually improve its services” (internal document) and “establishing an integrated governance structure” (internal document).

Chapter 6: New Entrants

Concurrently, another department within the municipality had discovered the potential of creative-purposive design. Being “the department with the most money” (R2), it simply “opened up a can of designers” (R2) and set up a team of 14 service and social designers (Team SD) within one and a half years. Suddenly, there were two “breeding grounds” (R5), which initially “got in each other’s way” (R5). Both teams, for example, developed different “principles for municipal services” (R3) and “customer segmentations” (R5), and started working on a “measuring house” (R4). Due to the sectoral mindsets in the organization, there was a tendency to compete rather than collaborate. Gradually, however, both teams established “warm contact” (R2) and began to work together more closely.

Chapter 7: This is Only the Beginning

Although Team SD has easier access to budget, it struggles to get into position and “fully realize the potential of design” (R7). Instead, it is mostly “tweaking in the margins” (R7). Accordingly, Team SD is determined to establish a strong track record and “build a legacy” (R7) in the years to come. Meanwhile, Team ID is engaged in various on-demand and self-initiated projects, as well as the program mentioned above. In addition, it is setting up another municipality-wide program on “Civil Affairs” (R3) - again including transformation as a secondary objective. While Team ID has come a long way, it still feels that “this is only the beginning” (R6); all these years of hard work mainly served to “create a context that enables transformation” (R3). Time will tell how this transformation will unfold.

Analysis

This section is divided into two parts. In the first part, we will shed light on the continuous adaptation and evolution of transformative work, thereby addressing RQ2. In the second part, we will describe how the engagement of public organizations with creative-purposive design evolves over time, thus offering answers to RQ3. This section is based on findings from both the focus groups and the case study.

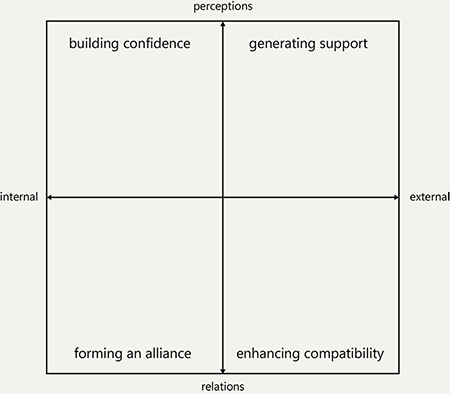

The Adaptation and Evolution of Transformative Work

We found that transformative work is highly situated. Practitioners are often not formally requested to engage in transformative work, thus limiting their means to do so. Within these constraints, practitioners strive to maximize their impact by aligning with the organization’s design capabilities, aligning with organizational and political priorities and demands, leveraging emergent opportunities, realizing synergies between transformative approaches, and continuously refining their transformative work. Accordingly, their transformative work becomes more strategically sophisticated over time.

Working With Constraints

First, we observed that practitioners adapt their transformative work to their capacities, resources, and mandate, which are often limited; practitioners are generally not formally requested to realize organizational transformation.

External practitioners explained that they are mainly hired to conduct creative-purposive design projects, provide creative-purposive design training, or facilitate longer-term experiential learning trajectories alongside actual projects that civil servants are working on: “Essentially, we always do design projects, and sometimes it leans more towards learning while other times it is more about execution” (A1). Deeper-level transformation is thus generally not part of their brief. Moreover, their reach into the organization is usually limited, as one of the participants in Focus Group D, who moved from being an outsider to being an insider explains: “I am really happy that I am on the inside now because from here I can do so much and I have a lot of access to things that I normally had to work really hard for” (D3). Thus, the transformative work of external practitioners mainly focuses on enhancing creative-purposive awareness and resources.

In contrast, internal practitioners described how they have a wider network within the organization, easier access to its resources, and a better understanding of its internal structures and culture, thus putting them in a better position to drive fundamental transformation. Given that they are not requested to engage in transformative work either, this mostly happens from the bottom up, on an informal basis: “This [transformative work] is a lot of work and it is not even my formal job. [...] Everything I do is informal” (C1). Accordingly, they lack the mandate or resources to mobilize others and instead rely on their position and reputation for this purpose. Team ID, for example, initially struggled to convince people from other departments, because they themselves were positioned in a different department; “nobody wanted this” (R4), because “you cannot improve something across siloes if you are coming from a silo yourself” (R4). Yet, as Team ID established a solid track record, it is now able to drive structural change. Meanwhile, the newer Team SD is still “tweaking in the margins” (R7).

Aligning With the Organization’s Design Capabilities

We also found that practitioners seek to align their transformative work with the organization’s design capabilities: “Depending on how far along they are, we are either in the lead or trying to enable them” (A1), “For many organizations, it’s about applying design for the first time and letting it lead to impact. But for some that are further along the way, it’s about strengthening their structure” (B2). This also means connecting with the organization’s established work processes and standards: “We work according to SAFe [Scaled Agile Framework] which includes the Double Diamond. We used that to say: look, SAFe says it too; we need to do the Double Diamond” (C1), “You can create prioritization frameworks, but there are already prioritization frameworks in place. So it is very important to create coherence with what already exists” (R4). Moreover, alignment entails leveling with prior knowledge of the people surrounding transformative work by “providing structures that they [the surrounding people] can hold onto” (A3), and “showing that it’s not rocket science” (A1). This may also imply “letting go of the qualities of design” (A5):

It’s not about making the best ideas or the coolest stuff. If you realize that you are also better to take them [the surrounding people] along with you. You know that if you do these interviews yourself, you may get much more out of it. But that is not the long-term goal. (A5)

Aligning With Organizational and Political Priorities and Demands

Furthermore, we found that practitioners try to align their transformative work to organizational and political priorities and demands. Generally, this does not mean that practitioners obtain the necessary resources and mandate to engage in transformative work: “There is no politician that prioritizes transformation, because citizens don’t understand it, so you can never put it on the agenda” (R5). However, it does provide them with the necessary resources and mandate for creative-purposive design work, enabling them to engage in transformative work simultaneously. Sometimes this is done openly, as we have seen in the thick description, where transformation was included as a secondary objective alongside the primary objectives of the program to improve the municipality’s services for entrepreneurs. Sometimes, however, this is done more covertly:

The really attentive steering group member or colleague may notice what is happening. But there is no explicit roadmap saying: “Now we’re going to add this role, now we’re going to ensure integrated funding, and now we’re moving forward.” This was a conscious decision because it will only create resistance, while so far, everyone is happy with what we’re doing. (R4)

Leveraging Opportunities for Transformation

Practitioners also explained how emergent organizational or political changes may offer a “window of opportunity” to accelerate transformation. In the thick description, we have seen several ways in which these opportunities were leveraged by Team ID. For example, by appointing the new general director as the CCO, or by strategically manoeuvring itself into the program to improve the municipality’s services for entrepreneurs. Similarly, one of the participants in Focus Group C explained how “you can also use the strategic goals to get things done” (C1):

In 2022, our board of directors made inclusion one of their spearheads. [...] And because of that, some budget became available. And that gave us the opportunity to start talking about design research as a method. Which is now creating quite a buzz. (C1)

Realizing Synergies between Transformative Approaches

Moreover, we have observed how practitioners try to maximize their impact by combining different transformative approaches to realize their synergistic potential; “you try to do all kinds of interventions in all kinds of ways and hope that, together, they help get this big organization in motion” (A1), “I see it [transformation] like playing simultaneous chess” (R5). Some approaches seem to particularly work well simultaneously. Perhaps the best example that we came across in this study concerns the community of practice that was established within a Dutch ministry, which connects like-minded people within the organization to “help and hold on to each other” (D3), developed a distinct brand and organizes all kinds of events to “create visibility” (D2), and has mobilized a general director as their ambassador to “make it [creative-purposive design] legitimate” (D2). Other combinations of efforts appear to work better in sequence. For example, the research that was conducted in the Town Room “didn’t necessarily contribute to the ultimate goal” (R2), but “served as a springboard to introduce design thinking within the organization” (R2). Moreover, the synergistic potential of different transformative approaches can be realized by working together with others inside or outside the organization: “We would do a lot of user research and then involve the designers, and the designers would say: we need research for this. So we also helped each other” (C1), “For us the outsourcing idea is really about showing: bang, this is what design can do, and you can also have it permanently in your team. [...] So the golden combo is working together internally and externally” (D2).

Fine-Tuning and Sophisticating Transformative Work

As practitioners gain experience, they get a better understanding of what to do and not to do, and fine-tune their transformative work accordingly. To illustrate, the participants in this study reflected on how requesting additional resources is generally “the quickest route to resistance” (R4), “so far only our bottom up attempts have worked” (C1), “in hindsight we did not approach it in the right way, because we came in like: we are going to teach this organization how to design” (C1), “I realized that people don’t know what to expect, so it’s important to have a good kick-off with everyone” (D2). In the thick description, too, we see how such learnings prompted Team ID to adapt its transformative work along the way, for example, by setting up an internal business model to continue growing from the bottom up and shifting to a co-creative approach.

With continuous refinement, the transformative work of Team ID gradually became more sophisticated. Initially, Team ID worked according to “the ‘you ask we deliver’ principle” (R2), thus “only doing reactive sales” (R3), and mainly focused on building a track record and growing the team. As it got into position, it started to “strategically choose projects” (R4) where the potential impact across the organization is big and the right conditions are present—i.e., “Does everyone agree on the problem and its urgency? Do we have the standard resources? So time, money, and mandate. And then also expertise” (R3). Currently, Team ID is even running a project that is “bound to fail” (R4), to demonstrate that: “We can try to improve our services, but we are in a system in which this is not possible” (R4). The team’s transformative work thus also became more daring. Moreover, as Team ID acquired structural funds and began “seeking more stable collaborations” (R6), it was able to drive transformation further and for a longer period. Furthermore, as discussed above, Team ID became more sensitive to emergent opportunities and strategic in leveraging them. Accordingly, Team ID’s transformative work shifted from opportunistic and improvisational to strategic and planned.

The Evolving Engagement of Public Organizations with Creative-Purposive Design

The practitioners involved in this study explained that while they develop an organization’s creative-purposive design capabilities, the organization’s engagement with creative-purposive design evolves; over time, creative-purposive design becomes easier, more diversified, robust, and expansive.

Enhanced Ease of Creative-Purposive Design

First, practitioners noted that, as the organization’s awareness of creative-purposive design increased, it became easier for them to do their creative-purposive design work. Over time, “people become comfortable with it [creative purposive design]” (B2), “it [creative-purposive design] becomes normal” (A5), and “people start understanding what we are doing” (R4). Consequently, “you can move much faster” (A4). Moreover, as practitioners establish longer-term collaborations with people within the organization, their relationships and interactions strengthen—i.e., they establish “warm contact” (R2), “mutual understanding” (A2), and “trust” (C2)—which promotes creative-purposive design work. Importantly, as practitioners manage to gain leadership support, creative-purposive design “becomes much easier” (R1) as well. The appointment of a CCO, for example, was crucial in legitimizing and facilitating the work of Team ID.

Diversification of Creative-Purposive Design Expertise

Moreover, we observed that meeting the demand for specific creative-purposive design work can have spillover effects, creating a demand for additional creative-purposive work that eventually results in the diversification of the organization’s creative-purposive design expertise. The example of the research conducted in the Town Room, which served as a springboard to introduce creative-purposive design, that we discussed earlier demonstrates this well. Over time, Team ID managed to create even more spillover effects and gradually expanded its expertise:

We started out with research. And then the need arose: we need to look at the bigger picture. That’s when service designers joined. And after that, we felt it would be even better if we added more UX maker’s capacities. (R1)

Enhanced Robustness of Creative-Purposive Design Practice

Additionally, we found that as practitioners develop their organization’s creative-purposive design capabilities, creative-purposive design becomes more robust. As Team ID raised awareness of creative-purposive design, grew a solid team, established a strong track record, built a good reputation, obtained structural funding, and developed creative-purposive design standards, the team not only secured a more stable position for itself, but it also carved out the organizational space to accommodate creative-purposive design. The team’s current work on developing the organizational capability to continually improve its services and establishing an integrated governance structure is likely to further anchor creative-purposive design within the organization’s structures.

Expansion of Creative-Purposive Design Work

Finally, we observed that as the organization’s creative-purposive design awareness and culture develop, the use of creative-purposive design expands in breadth, depth, and significance—and so do the roles of creative-purposive designers:

It is a bit of a domino effect. First, you have to convince them that you are not a graphic designer. [...] And then they start involving you at the end of the innovation process. Or the day before they want to do a creative session. And at some point, they think: wait, maybe I should start involving her a bit earlier in the process. (D2)

This development is also clearly visible in the thick description. As Team ID developed a broad portfolio of projects across the organization, the organization eventually dared to make the team responsible for running the municipality-wide program to enhance its services for entrepreneurs in a creative-purposive manner. This is a substantial step, as the program is highly visible and there is a lot at stake for it to succeed, not least because politicians seek to score points with the program.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

This study provides a deep insight into the complex dynamics of creative-purposive design-enabling transformation of public organizations. The thick description of the transformative journey of a Dutch municipality vividly illustrates the twists and turns, alternating periods of stagnation, incremental progress, and moments of breakthrough or disruption along the way. It clearly reflects the broad notion that transformation is difficult, messy, and unpredictable (e.g., Burnes, 2005; McDaniel, 2007; Styhre, 2002). Yet, this study also highlights that certain knowable and sometimes foreseeable factors shape the course of transformation. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Lewis et al., 2020; Karpen et al., 2022; Torfing et al., 2019), this study demonstrates how established institutions, bureaucracy, and politics often hinder progress. Conversely, events typically seen as disruptive—such as job rotations, political changes, and strategic shifts (e.g., Kang & Prendiville, 2018; McGann et al., 2021; Pirinen, 2016)—can present opportunities to accelerate transformation. Most importantly, this study emphasizes that the key factor driving transformation is sustained transformative work.

Many studies note that transformative work often gives rise to significant challenges, tensions, and frictions (e.g., Boztepe et al., 2023; Pirinen et al., 2022; Starostka et al., 2022) and thus rarely leads to lasting organizational transformation (Brinkman et al., 2023; Boztepe et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2022; Malmberg, 2017). However, this study highlights that the pitfalls and obstacles encountered in transformative work give rise to continuous learning and adaptation, thereby enabling practitioners to navigate the complex dynamics of transformation strategically. We have seen how practitioners are generally not given a ”license to operate” for their transformative work, necessitating persistent transformative entrepreneurialism. Transformative work often follows the “Trojan horse approach” described by Szücs Johansson et al. (2017); it is undertaken alongside creative-purposive design work, which is more likely to receive organizational support and resources. Within their capacities, practitioners strive to maximize their impact by simultaneously, sequentially, or collaboratively combining different transformative approaches and continuously refining them. Over time, practitioners develop their strategic intelligence, making their transformative work increasingly sophisticated and effective.

As transformative work is sustained and becomes increasingly sophisticated, public organizations progressively develop their creative-purposive design capabilities. Accordingly, their engagement with creative-purposive design evolves. In line with the findings of Hyysalo et al. (2023) and Kim (2023), this study demonstrates how creative-purposive design in public organizations gradually becomes easier, more diversified, and more robust, and its use expands in breadth, depth, and significance. Interestingly, given that transformative work is often undertaken alongside creative-purposive design work, this too becomes easier, more diversified, robust, and expansive. Accordingly, this study demonstrates that transformative work is closely intertwined with the transformation it brings about; as public organizations gradually open up to creative-purposive design, practitioners are increasingly authorized to drive organizational transformation. In other words, transformation and transformative work continuously co-evolve.

Building on earlier work of Malmberg (2017), we adopted the perspective that design capabilities are determined by four interrelated dimensions—i.e., an organization’s design awareness, resources, structures, and culture. However, in this study, we have seen how design capabilities are also defined by their local enactment, in interaction with others, and in relation to the (wider) organizational environment. Design capabilities are thus inherently interactive and relational. This insight suggests that further theorizing of design capabilities could benefit from a complexity perspective.

A key limitation of this study lies in the fact that most of our participants worked with public organizations in the Netherlands, which are known for their collaborative, decentralized approach to working and openness to innovation. This likely explains the extensive transformative entrepreneurialism that we observed in this study, which may not be feasible nor effective in public organizations that are more hierarchical and bureaucratic. Furthermore, we observed that frameworks such as the Theory of Change logic model and the Public Sector Design Ladder (Design Council, 2013) presume a linearity that does not correspond to the messy reality of organizational transformation, making it difficult for participants to directly draw from their own experiences, causing them to speak in abstract terms and thus limiting the depth of insights that were gained in the focus groups in which these frameworks were used. Finally, the focus groups conducted with external professionals, who are often bound by temporary engagements, provided fewer insights into how transformation unfolds and how transformative work evolves.

We are particularly intrigued by the co-evolutionary dynamic of transformation and transformative work revealed in this study, as it opens up several avenues for future research. First, we propose studying the co-evolutionary pathways of transformation and transformative work in various (non-Western) administrative contexts. This could illuminate how vicious cycles arise and virtuous cycles can be fostered. Additionally, this could reveal the conditions under which co-evolution may lead to unwanted path-dependencies or lock-ins that hinder the ongoing development of a public organization’s design capabilities. Furthermore, we recommend additional research on the co-evolutionary learning and adaptation that happens between the practitioners engaged in transformative work and those surrounding it, as this could yield valuable insights into fostering productive interactions and strategically shifting co-evolutionary pathways. Finally, the co-evolution between rational-instrumental and creative-purposive design warrants further exploration to better understand how synergies between these complementary design orientations can be realized.

Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank all the participants in this study for their willingness to share their experiences with us and for their openness in doing so.

Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bailey, S. G. (2012). Embedding service design: The long and the short of it. Developing an organisation’s design capacity and capability to sustainably deliver services. In P. J. Tossavainen, M. Harjula, & S. Holmlid (Eds.), ServDes 2012: Co-creating services (pp. 31-41). Design Research Society. https://doi.org/10.21606/servdes2012.13s

- Bason, C. (2014). Design for policy. Routledge.

- Bason, C., & Austin, R. D. (2021). Design in the public sector: Toward a human centred model of public governance. Public Management Review, 24(11), 1727-1757. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1919186

- Blomkamp, E. (2018). The promise of co-design for public policy. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77(4), 729-743. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12310

- Bowen, G. A. (2006). Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), 12-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500304

- Boztepe, S., Linde, P., & Smedberg, A. (2023). Design making its way to the city hall: Tensions in design capacity building in the public sector. In D. de Sainz Molestina, L. Galluzzo, F. Rizzo, & D. Spallazzo (Eds.), IASDR 2023: Life-changing design (Article No. 159). Design Research Society. https://doi.org/10.21606/iasdr.2023.458

- Boztepe, S., de Götzen, A., Keinonen, T., Christiansson, J., & Hepburn, L. A. (2024). Rethinking design in the public sector: A relational turn. International Journal of Design, 18(3), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.57698/v18i3.01

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Breen, R. L. (2006). A practical guide to focus-group research. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 30(3), 463-475. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260600927575

- Brinkman, G., van Buuren, A., Voorberg, W., & van der Bijl-Brouwer, M. (2023). Making way for design thinking in the public sector: A taxonomy of strategies. Policy Design and Practice, 6(3), 241-265. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2023.2199958

- Brinkman, G., & Kim, A. (2024). Reframing design maturity: A new perspective on the development of design in public organizations. In C. Gray, E. Ciliotta Chehade, P. Hekkert, L. Forlano, P. Ciuccarelli, & P. Lloyd (Eds.), DRS2024: Research papers (Article No. 304). Design Research Society. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2024.973

- Buchanan, R. (2001). Design research and the new learning. Design Issues, 17(4), 3-23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1511916

- Burnes, B. (2005). Complexity theories and organizational change. International Journal of Management Reviews, 7(2), 73-90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00107.x

- By, R. T. (2005). Organisational change management: A critical review. Journal of Change Management, 5(4), 369-380. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010500359250

- Carstensen, H. V., & Bason, C. (2012). Powering collaborative policy innovation: Can innovation labs help? The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, 17(1), Article 4.

- Clarke, A., & Craft, J. (2018). The twin faces of public sector design. Governance, 32(1), 5-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12342

- Crosby, B. C., ‘t Hart, P., & Torfing, J. (2017). Public value creation through collaborative innovation. Public Management Review, 19(5), 655-669. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1192165

- David, P. A. (1994). Why are institutions the ‘carriers of history’?: Path dependence and the evolution of conventions, organizations and institutions. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 5(2), 205-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0954-349X(94)90002-7

- Deserti, A., & F. Rizzo. (2015). Design and organizational change in the public sector. Design Management Journal, 9(1), 85-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmj.12013.

- Design Council. (2013, June 3). Design for public good. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/archive/reports-resources/design-public-good/

- Elsbach, K. D., & Stigliani, I. (2018). Design thinking and organizational culture: A review and framework for future research. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2274-2306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317744252

- Enserink, B., Koppenjan, J. F., & Mayer, I. S. (2013). A policy sciences view on policy analysis. In W. Thissen & W. Walker (Eds.), Public policy analysis: New developments (pp. 11-40). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4602-6_2

- Galletta, A. (2013). Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: From research design to analysis and publication (Vol. 18). NYU Press.

- Grobman, G. (2005). Complexity theory: A new way to look at organizational change. Public Administration Quarterly, 29(3), 351-384. https://doi.org/10.1177/073491490502900305

- Head, B. W. (2010). How can the public sector resolve complex issues? Strategies for steering, administering and coping. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 2(1), 8-16. http://doi.org/10.1108/17574321011028954

- Head, B. W., & Alford, J. (2015). Wicked problems: Implications for public policy and management. Administration & Society, 47(6), 711-739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399713481601

- Head, B. W. (2022). Wicked problems in public policy: Understanding and responding to complex challenges. Springer Nature. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/53360

- Hermus, M., van Buuren, A., & Bekkers, V. (2020). Applying design in public administration: A literature review to explore the state of the art. Policy & Politics, 48(1), 21-48. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557319X15579230420126

- Holmlid, S., & Malmberg, L. (2018). Learning to design in public sector organisations: A critique towards effectiveness of design integration. In Proceedings of the conference on service design and service innovation (pp. 37-48). Design Research Society. https://doi.org/10.21606/servdes2018.63

- Howlett, M. (2019). Designing public policies: Principles and instruments. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315232003

- Hyysalo, S., Savolainen, K., Pirinen, A., Mattelmäki, T., Hietanen, P., & Virta, M. (2023). Design types in diversified city administration: The case city of Helsinki. The Design Journal, 26(3), 380-398. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2023.2181886

- Joosse, H., & Teisman, G. (2021). Employing complexity: Complexification management for locked issues. Public Management Review, 23(6), 843-864. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1708435

- Junginger, S. (2014). Design legacies: Why service designers are not able to embed design in the organization. In Proceedings of the 4th conference on service design and service innovation (pp. 164-172). Linköping University Electronic Press. https://ep.liu.se/en/conference-issue.aspx?issue=99

- Junginger, S. (2017). Transforming public services by design: Re-orienting policies, organizations and services around people. Routledge.

- Kang, I., & Prendiville, A. (2018). Different journeys towards embedding design in local government in England. In A. Meroni, A. M. Ospina Medina, & B. Villari, B. (Eds.), ServDes 2018: Service design proof of concept (Article No. 91). Design Research Society. https://doi.org/10.21606/servdes2018.91

- Kang, I. (2021). Embedding design in local government: Role of designers and public servants [Doctoral dissertation, University of the Arts London]. UAL Research Online. https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/16672

- Karpen, I. O., Vink, J., & Trischler, J. (2022). Service design for systemic change in legacy organizations: A bottom-up approach to redesign. In B. Edvardsson & B. Tronvoll (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of service management (pp. 457-479). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91828-6_24

- Kim, A. (2023). Embedding design practices in local government: A case study analysis [Doctoral dissertation, Delft University of Technology]. TU Delft Repository. https://doi.org/10.4233/uuid:0be72865-8064-4120-8103-c57b1321a3f0

- Kimbell, L., & Bailey, J. (2017). Prototyping and the new spirit of policy-making. CoDesign, 13(3), 214-226. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355003

- Kleiber, P. B. (2003). Focus groups: More than a method of qualitative inquiry. In K. B. de Marrais & S. D. Lapan (Eds.), Foundations for research (pp. 103-118). Routledge.

- Kuipers, B. S., Higgs, M., Kickert, W., Tummers, L., Grandia, J., & Van der Voet, J. (2014). The management of change in public organizations: A literature review. Public Administration, 92(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12040

- Lewis, J. M., McGann, M., & Blomkamp, E. (2020). When design meets power: Design thinking, public sector innovation and the politics of policymaking. Policy & Politics, 48(1), 111-130. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557319X15579230420081

- Lewis, J. M. (2021). The limits of policy labs: Characteristics, opportunities and constraints. Policy Design and Practice, 4(2), 242-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1859077

- Lima, F. A., & Sangiorgi, D. (2018). Fostering a sustained design capability in non-design-intensive organizations: A knowledge transfer perspective. In A. Meroni, A. M. O. Medina, & B. Villari (Eds.), ServDes 2018: Service design proof of concept (Article No. 64). Design Research Society. https://doi.org/10.21606/servdes2018.64

- Malmberg, L., & Wetter-Edman, K. (2016). Design in public sector: Exploring antecedents of sustained design capability. In Proceedings of the 20th conference of academic design management on inflection point (pp. 1287-1307). Design Management Institute.

- Malmberg, L. (2017). Building design capability in the public sector: Expanding the horizons of development (Vol. 1831). Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Marion, R., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2001). Leadership in complex organizations. The Leadership Quarterly, 12(4), 389-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(01)00092-3

- McDaniel Jr, R. R. (2007). Management strategies for complex adaptive systems sensemaking, learning, and improvisation. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 20(2), 21-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-8327.2007.tb00438.x

- McGann, M., Blomkamp, E., & Lewis, J. M. (2018). The rise of public sector innovation labs: Experiments in design thinking for policy. Policy Sciences, 51(3), 249-267. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9315-7

- McGann, M., Wells, T., & Blomkamp, E. (2021). Innovation labs and co-production in public problem solving. Public Management Review, 23(2), 297-316. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1699946

- Meijer-Wassenaar, L., & Bakker-Joosse, M. (2023). In-house designers to break out public sector auditing in a manageable way. In D. de Sainz Molestina, L. Galluzzo, F. Rizzo, & D. Spallazzo (Eds.), IASDR 2023: Life-changing design (Article No. 51). Design Research Society. https://doi.org/10.21606/iasdr.2023.769

- Morgan, D. L. (1996). Focus groups as qualitative research (Vol. 16). Sage.

- Mulgan, G., & Albury, D. (2003). Innovation in the public sector. https://alnap.org/help-library/resources/innovation-in-the-public-sector/

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage.

- Pirinen, A. (2016). The barriers and enablers of co-design for services. International Journal of Design, 10(3), 27-42. https://doi.org/10.57698/v10i3.03

- Pirinen, A., Savolainen, K., Hyysalo, S., & Mattelmäki, T. (2022). Design enters the City: Requisites and points of friction in deepening public sector design. International Journal of Design, 16(3), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.57698/v16i3.01

- Ponterotto, J. G. (2006). Brief note on the origins, evolution, and meaning of the qualitative research concept thick description. The Qualitative Report, 11(3), 538-549. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2006.1666

- Rauth, I., Carlgren, L., & Elmquist, M. (2014). Making it happen: Legitimizing design thinking in large organizations. Design Management Journal, 9(1), 47-60. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmj.12015

- Riaz, S., Morgan, D., & Kimberley, N. (2023). Managing organizational transformation (OT) using complex adaptive system (CAS) framework: Future lines of inquiry. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 36(3), 493-513. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-08-2022-0241

- Schaminee, A. (2018). Designing with and within public organizations: Building bridges between public sector innovators and designers. BIS Publishers.

- Mortati, M., Mullagh, L., & Schmidt, S. (2022). Design-led policy and governance in practice: A global perspective. Policy Design and Practice, 5(4), 399-409. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2022.2152592

- Schneider, M., & Somers, M. (2006). Organizations as complex adaptive systems: Implications of complexity theory for leadership research. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(4), 351-365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.04.006

- Stacey, R. D. (1995). The science of complexity: An alternative perspective for strategic change processes. Strategic Management Journal, 16(6), 477-495. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250160606

- Starostka, J., de Götzen, A., & Morelli, N. (2022). Design thinking in the public sector–A case study of three Danish municipalities. Policy Design and Practice, 5(4), 504-515. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2022.2144817

- Starostka, J., de Götzen, A., & Morelli, N. (2023). Design facilitation in public sector–Learnings from public libraries in Denmark. In Proceedings of the 6th international conference on public policy. Toronto Metropolitan University’s Faculty of Arts and Public Policy.

- Starostka, J., Neuhoff, R., Morelli, N., & Simeone, L. (2024). Design facilitation: Navigating complexity for collaborative solutions to urban sustainability challenges. In C. Gray, E. Ciliotta Chehade, P. Hekkert, L. Forlano, P. Ciuccarelli, & P. Lloyd (Eds.), DRS2024: Boston (Article No. 116). Design Research Society. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2024.500

- Styhre, A. (2002). Non-linear change in organizations: Organization change management informed by complexity theory. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 23(6), 343-351. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730210441300

- Szücs Johansson, L., Vink, J., & Wetter-Edman, K. (2017). A Trojan horse approach to changing mental health care for young people through service design. Design for Health, 1(2), 245-255. https://doi.org/10.1080/24735132.2017.1387408

- Terry, N. (2012). Managing by design: A case study of the Australian Tax Office [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Canberra.

- Tõnurist, P., Kattel, R., & Lember, V. (2017). Innovation labs in the public sector: What they are and what they do? Public Management Review, 19(10), 1455-1479. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1287939

- Torfing, J., Sørensen, E., & Røiseland, A. (2019). Transforming the public sector into an arena for co-creation: Barriers, drivers, benefits, and ways forward. Administration & Society, 51(5), 795-825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399716680057

- Turnbull, N. (2018). Policy design: Its enduring appeal in a complex world and how to think it differently. Public Policy and Administration, 33(4), 357-364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076717709522

- van Buuren, A., Lewis, J. M., & Peters, B. G. (Eds.). (2023). Policy-making as designing: The added value of design thinking for public administration and public policy. Policy Press.

- von Thienen, J., Meinel, C., & Nicolai, C. (2014). How design thinking tools help to solve wicked problems. In L. Leifer, H. Plattner, & C. Meinel (Eds.), Design thinking research (pp. 97-102). Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01303-9_7

- Vink, J., & Koskela-Huotari, K. (2022). Building reflexivity using service design methods. Journal of Service Research, 25(3), 371-389. https://doi.org/10.1177/10946705211035004

- Werkman, R. A. (2009). Understanding failure to change: A pluralistic approach and five patterns. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 30(7), 664-684. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730910991673

- Yeo, Y., Lee, J. J., & Yen, C. C. (2023). Mapping design capability of governments: A tool for government employees’ collective reflection. International Journal of Design, 17(1), 17-35. https://doi.org/10.57698/v17i1.02

Appendix

Appendix A: Visual Prompts Used During the Focus Groups

Taxonomy of strategies

Figure A.1. The taxonomy of strategies to make way for creative-purposive design (based on Brinkman et al., 2023) that was used in Focus Group A.

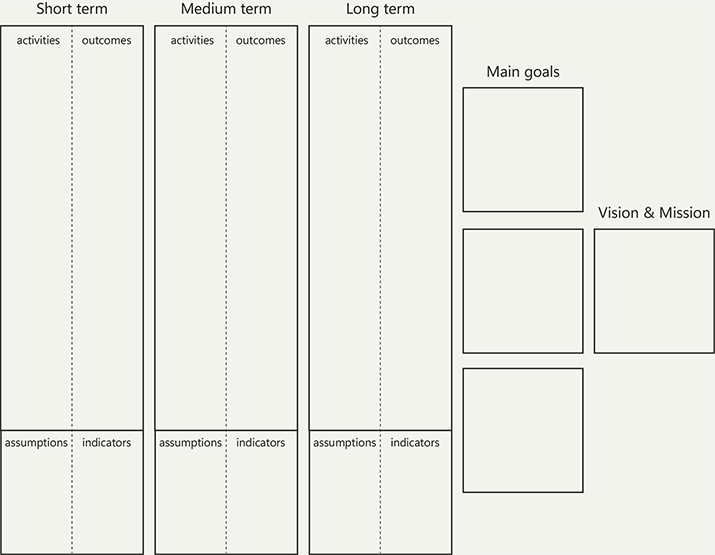

Theory of Change logic model

Figure A.2. The Theory of Change logic model framework that was used in Focus Group B.

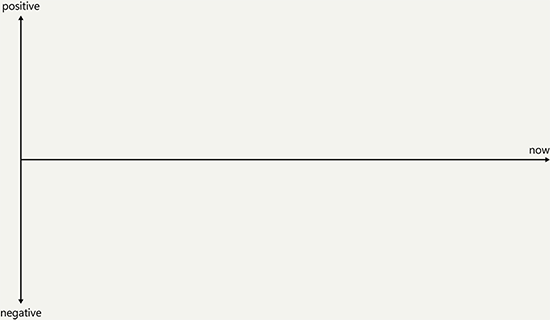

Transformation pathway

Figure A.3. The timeline that was used in Focus Group C.

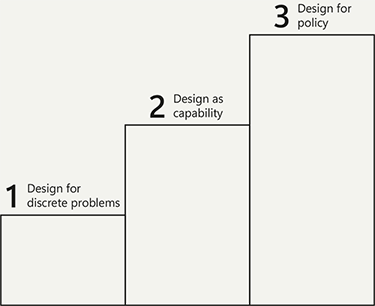

Public sector design ladder

Figure A.4. The Public Sector Design Ladder (based on Design Council, 2013) that was used in Focus Group C.

Appendix B: Visual Prompts Used During the Interviews

Applications of design

Figure B.1. The onion model of the four orders of design (based on Buchanan, 2001) that was used during the interviews.

Design inside or outside the organization

Figure B.2. The organizational chart that was used during the interviews.

Design maturity

Figure B.3. The framework of design maturity (based on Brinkman & Kim, 2024) that was used during the interviews.

Transformation pathway

Figure B.4. The timeline that was used during the interviews.

Appendix C: The Coding Tree Resulting from Our Thematic Analysis

Table C.1. The coding tree resulting from our thematic analysis.