Knowledge Mapping: User Research for Plural, Just, and Equitable Co-Creation Interface Design

Niti Bhan 1,* and Laras Zita Tedjokusumo 2

1 Aalto University, Espoo, Finland

2 Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, Helsinki, Finland

A plurality of knowledge systems remains unseen and unrecognized as invisible social structures that underpin lifestyles, life chances, and livelihoods of peoples. The legacy of imperialism and colonialism has suppressed, erased, and marginalized indigenous knowledge traditions and non-Western knowledge systems. A cultural interface between Western and non-Western knowledge systems is yet to be recognized as being instantiated during co-creation. We test a prototype of a sequential multi-phase inquiry protocol for user research to explore indigenous knowledge traditions of community preparedness for volcanic eruptions in Indonesia and introduce knowledge mapping. Knowledge mapping at the front-end of co-creation helps prepare, plan, and design interfaces for collaborations in conditions of epistemological plurality. A knowledge products map illustrates epistemic complexity of an indigenous co-creation interface. Knowledge mapping complements and enhances other service design methods such as stakeholder mapping, customer journeys, systems maps, etc. The protocol is designed to incorporate principles of indigenous research paradigms and a just and plural lens for inquiry to guide implementation of Western-theorized methods and tools. This methodological development considers entire knowledge systems as service design materials, with the aim to facilitate conditions for plural, just, and equitable co-creation.

Keywords – Co-Creation, Cultural Interface, Indigenous Research Paradigms, Knowledge Mapping, Knowledge Products Map, User Research.

Relevance to Design Practice – Knowledge mapping at the front-end of co-creation may be used to complement or replace stakeholder mapping, depending on purpose and goals of co-creation. It facilitates design of co-creation interfaces when non-Western knowledge systems must collaborate with the Western, to ensure just and equitable cognitive representation, in addition to participation.

Citation: Bhan, N., & Tedjokusumo, L. Z. (2025). Knowledge mapping: User research for plural, just, and equitable co-creation interface design. International Journal of Design, 19(3), 83-99. https://doi.org/10.57698/v19i3.04

Received May 31, 2024; Accepted October 30, 2025; Published December 31, 2025.

Copyright: © 2025 Bhan & Tedjokusumo. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-access and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: niti.bhan@aalto.fi

Niti Bhan returns to academic scholarship after two decades of professional design practice specializing in exploratory user research customized for informal economic systems, primarily in East Africa and South-East Asia. Recognition of her work includes invitations to speak (Closing Plenary, CHI2007; TED Global, 2017), write (Core77 2004-2010; Harvard Business Review, 2014), and participate (UNESCO Social Design Network Advisory Board 2007-2010; Core77 Design Awards 2022 Jury). Her research aims to build bridges across epistemes, ontologies, and epistemologies for sustainable design futures. Formerly, she was Director, Graduate Admissions, Institute of Design, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago (2002-2005).

Laras Zita Tedjokusumo is an Indonesian visual communication designer and sustainability strategist. After completing her MA in Creative Sustainability from Aalto University School of Arts, Design, and Architecture, she works as project manager (design) in the Research, Development, and Innovation department, Metropolia University of Applied Sciences in Helsinki, Finland.

“...it is critical for us [to] develop deeper understandings of how we are positioned at the interface of different knowledge systems, histories, traditions, and practices.”

(Nakata, 2007a, p. 12)

Introduction

A world exists outside the Euro-Western academy, its pedagogy, and its discourse. Knowledge continues to be created, preserved, and transmitted across generations. There is a thriving pluriverse of living, breathing indigenous knowledge systems, each contributing to lives and livelihoods (Du Plessis & Raza, 2004; Visvanathan, 1997). These creative worlds remain invisible, due to the colonial and imperial legacy of deliberate marginalization, suppression, and erasure (Chilisa, 2017; Mignolo, 2007, 2023; Smith et al., 1999). The potential of user research to contribute to a change in the landscape of epistemology has not yet been explored. As Western-educated post-colonial Asian service designers operating in epistemological plurality, we are intrinsically motivated to respond to the blind spots created by this legacy.

British historians of science Andrew Cunningham and Perry Williams (1993) mark an important inflection point in the history of the Western knowledge system. In their own words:

The old big picture [was] rooted in transcendent timeless logic and embodying absolute moral values of freedom, rationality and progress: a universal human enterprise. But a new big picture must be based on the emerging re-conception of science as [emphasis added] historically contingent and embodying the values, aims and norms of a particular social group: one amongst a plurality of ways of knowing the world [emphasis added]. In a new big picture, what we refer to as ‘science’ can no longer be used as a general defining framework; it must be seen as limited, bounded in time and space and culture. (p. 418)

In this ‘new big picture’, scientific knowledge production is a situated social practice: a ‘local knowledge’ (Turnbull, 2009), and only one among a plurality of knowledges indigenous to their locality and society (Cobern & Loving, 2001). However, Esther Turnhout (2024) argues that science has itself become an obstacle for the transformations needed to ensure human-ecological well-being, primarily due to the dominant norms and conceptualizations of what science is, and which continue to marginalize alternative forms of knowledge. Like any other invisible social structure in highly institutionalized contexts (Vink & Koskela-Huotari, 2021), these dominant norms and conceptualizations of what science is create an epistemological blindspot for the sustainability transformations now recognized as a driving force for knowledge production (Jacobi et al., 2022; Klein, 2023; Turnhout, 2024).

It is increasingly recognized that addressing the polycrisis in ways that are not just effective but also equitable and just [emphasis added] will require deep transformative change of political, economic and cultural structures, paradigms and practices. (Turnhout, 2024. p.2)

We highlight Turnhout’s use of equitable and just as qualifiers for co-creation. A recent study on 54 sustainable development research projects demonstrates a clear link between successful “utilization of research knowledge for sustainability transformations” and convening “academic and non-academic actors in a setting that enables discussions on an even footing and the empowering of actors who are often not heard” (Jacobi et al., 2022, p. 107). Co-creation has become the de facto approach to knowledge production (Ferreira et al., 2023; Larivière et al., 2015; Wuchty et al., 2007). Trends over the past half century point to increasing research team size (Henriksen, 2016), as seen in the proliferation of publications with ten or more co-authors (Jakab et al., 2024). Scientists are now arguing for co-creation expertise as a necessary part of graduate education, not just individual expertise in a discipline (Kawa et al., 2021).

However, the current epistemological infrastructure is not designed to satisfy the requirements for just and equitable co-creation with knowledge traditions that fall outside the boundaries of the Euro-Western academy (Chilisa, 2017; Klein, 2023; Turnhout, 2024). The legacy of hegemonic knowledge production continues to perpetuate a blind spot. For instance, Baulenas et al. (2023) develop a framework for user selection for climate services co-creation in Western Europe, while Vogelsang et al. (2025) develop a roadmap for co-creation protocols in British healthcare. However, a clear gap remains visible for practical mechanisms that support co-creation with indigenous knowledge-holders (Kuokkanen, 2017; Tengö et al., 2021). This motivates our research and development of user research for co-creation in conditions of epistemological plurality, as a form of epistemologically-sensitive service design.

We introduce our prototype for user research on indigenous disaster preparedness knowledge among communities residing on an active volcano in Java, the Indonesian island, grounded in post-colonial indigenous research paradigms (Chilisa, 2019) as proof of concept. Nakata’s cultural interface theory (2007a, 2010) provides an epistemological bridge between the theoretical landscape of service design (Rytilahti et al., 2015) and indigenous knowledge traditions in the form of an interface amenable to service design. Nakata promotes search for common ground between (often) incommensurable knowledge systems for reconciliation and bridge building (Yunkaporta, 2009). Incorporating decolonial thought (Tlostanova & Mignolo, 2009) in the form of cognitive justice (Visvanathan, 1997, 2005) ensures recognition of a plurality of knowledges and just and equitable conditions for engagement (Coolsaet, 2016; Rodriguez, 2017). This generates a theoretically grounded conceptual frame for supporting design of co-creation interfaces in conditions of epistemological plurality.

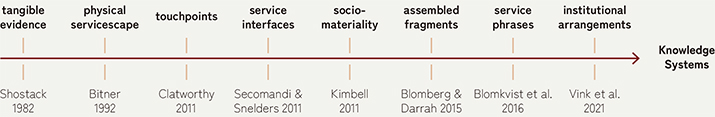

Three touchpoints inform the sequential structure of our user research prototype. We call this structured sequence knowledge mapping, and illustrate the complexity of instantiated cultural interfaces with a knowledge products map. How we represent our users informs how we design. Our representation is informed by our choice of research paradigm and the lens through which we conduct our inquiry. This influences the outcomes of the collaborative processes; therefore, we extend Vink and Koskela-Huotari’s (2021) timeline of service design materials by the addition of entire knowledge systems. In this way, our contribution also serves as a decolonial intervention in the processes of co-creation. This summarizes the article’s structure.

Methodological Development

The first author pioneered exploratory user research for payment plans and business models in rural South East Asia more than 15 years ago (Bhan, 2009a, 2009b), extending user research (Wasson, 2000) from first- and second-order design to the third- and fourth-order (Buchanan, 2001). Since then, the firm, founded and managed by the first author, has delivered custom-designed user research protocols (e.g., Bhan & Gajera, 2018). This practice inspired the second author’s request for a ‘learning by doing’ opportunity, and went on to test the prototype for user research developed by the first author. This chapter walks us through the entire process and then discusses the prototype test. As co-creators of research among marginalized knowledge-holders, our deliberations on positionality are included in our methodological development process.

Background

We do not begin with a pre-determined definition of co-creation when a plurality of epistemologies are involved so much as we derive our way towards understanding it from first principles. Designing ‘from first principles’ assumes the theoretical position that designing proceeds by identifying requirements, or desired functions, and arguing from these to appropriate forms or structures (Cross, 1997). The notion of surprise, as an impetus for evolutionary development being used as an analogy for the non-linear and messy process of design, is almost as old as design research as an academic pursuit (Schön 1983; Dorst & Cross, 2001; Gaver et al., 2022). Our research was punctuated by ‘surprises’, and includes field results of ‘emergence’, both parts of the process (Cross, 1997; Gaver et al., 2022) of realizing a design through exploration of a problem space (Höök & Löwgren, 2012). Today, such explorations are understood to be far more open-ended in tandem with the opening up of problem spaces (Lee et al., 2018). However, these efforts tend to remain suppressed by normative pressures of the academy (Gaver et al., 2022). Our own account, then, can only be considered the end result, or day science, where “to write an account of research is...to transform the very nature of the research; to formalise it. To substitute an orderly train of concepts and experiments for a jumble of disordered efforts” (Jacob, 2001, cited by Gaver et al., 2022, p. 2-3). The second author aspired to design a bridge between Indonesia’s national disaster preparedness strategies and the ‘local wisdom’ of communities, for which the first author served as the external advisor for the project. Surprises helped develop our prototype for user research, guide it through the final stage-gate of decision-making, and surface indigenous knowledge products after multiple rounds of translation.

Prior Art

Duan et al. (2021) describe how the ‘hubris of the zero point gaze’ (Castro-Gomez, 2021) plays out in the dominant narratives of service design. The story of practice—regardless of locality or practitioner—is narrated only through concepts related to service design knowledge (Duan et al., 2021). In our interpretation of their argument, it is the hegemonic epistemological infrastructure of the Euro-Western academy (Kuokkanen, 2017) that creates epistemic conditions in which service design literature not only ignores the heterogeneity of cultures, worldviews, and peoples (Duan et al., 2021) but also generates a monolithic view of a universal reality. In essence, Duan (2024) has problematized cultural plurality in service design. We extend these well-considered and robust arguments for recognizing a plurality of worldviews, beliefs, and knowledges—captured under the umbrella term of ‘culture’ by Duan (2024)—for explicit recognition of a plurality of knowledge systems, and their epistemologies, axiologies, and cosmologies, in addition to ontologies. That is, our beliefs and our worldviews are inextricable from our knowledge system (Kuokkanen, 2017). Coloniality, when unpacked, directs our attention to the hegemonic capture of knowledge and its production practices (Mignolo, 2007; Tlostanova & Mignolo, 2009). Decoloniality requires practical mechanisms for unpacking the monolithic view prevalent in service design (Duan et al., 2021). It is from this stance of recognizing there is much more complexity in plurality (Karpen et al., 2021) when we aim to co-create with Indigenous and other non-Western knowledge-holders (Bhan & Vienni-Baptista, 2025) that we begin our design methodological development of user research.

It is only very recently that we see common dimensions of a co-creation theory synthesized from multiple different disciplines (Messiha et al., 2025) or roadmaps for co-creation protocols (Vogelsang et al., 2025). Interestingly, these studies are not from design, but discovered through a citation search of Lee et al.’s (2018) Design Choices Framework for Co-creation Projects, which aims to facilitate planning of co-creation. One considers Lee et al. (2018) a pre-cursor of design knowledge products to support planning and instantiation of co-creation. Smeenk (2023), for instance, builds a working prototype from Lee et al.’s (2018) theoretical framework. Both are instances of intermediate-level knowledge (Höök & Löwgren, 2012) and foreground diversity of knowledge as instrumental in co-creation (Lee et al., 2018).

According to Lee et al. (2018), the diversity of knowledge of participants in a co-creation initiative is informed by two requirements: hologram structure and holistic knowledge. Hologram structure cites Smeds’ framework (1994) for its definition as “the practice-based knowledge of all identified stakeholders (organizations, functions, business areas, hierarchical levels, customers, etc.) whose practices will be affected by the co-created product, service or process” (Lee et al., 2018, p. 22). Holistic knowledge is described as the requirement that the combined knowledge of everyone involved in the collaborative process provides all the knowledge needs required to realize their co-creation. However, Lee et al. (2018) do not suggest any means for mapping the knowledge base across all stakeholders and held amongst them. To the best of our knowledge, no methods or tools are currently available.

As pre-cursors, we reviewed cultural mapping (Duxbury & Garrett-Petts, 2024) and disciplinary mapping (Rasmussen et al., 2010), both of which are complementary practices at the front-end of pluralistic collaborations. Cultural mapping is pragmatically defined as “a process of collecting, recording, analysing and synthesizing information in order to describe the cultural resources, networks, links and patterns of usage of a given community or group” (Duxbury et al., 2015, p. 2). Participatory cultural mapping is a form of co-creation “to make visible and co-produce knowledge that is of value for community identity formation, reflection, decision-making, and development” (Duxbury & Garret-Petts, 2024, p. 329). It is situated as a cartographic method for making meaningful sense of a place. From the work of Duxbury and Garret-Petts (2024), we took away the message that “developing theoretically grounded, pragmatic approaches to recognising, appreciating and bringing together different types of knowledges and perspectives is needed” (p. 334). Rasmussen et al. (2010) provide deep insights on futures-oriented knowledge co-creation with a variety of stakeholders. Skilled facilitation is required to extend collective creativity into the uncertainty of an emerging future, and facilitation is an entire phase of work at the front-end of co-creation, not just during the actual manifestation of an interface (Rasmussen et al., 2010). However, their label of ‘disciplinary mapping’ reveals their operating assumption that all stakeholders will share an epistemological tradition; that of the hegemonic knowledge system. This is part of the monolithic view in design, as identified by Duan et al. (2021), which permeates the literature. For existing tools such as stakeholder mapping and interest analysis, we turned to Nielsen and Bjerke (2022), who use case studies to uncover gaps and limitations in crafting their argument for new tools and vocabularies in service design.

Cobern and Loving (2001) concluded that epistemological pluralism is the only stance available to us today, based on their extensive discussion on the philosophy and theories of science. Their arguments reveal the practical implications of the hegemonic tendency of the academy to “co-opt and dominate indigenous knowledge if it were incorporated as science” (Cobern & Loving, 2001, p. 50). The outcome of such coloniality (Mignolo, 2007; Tlostanova & Mignolo, 2009) is devaluation, not only of other knowledge traditions, but as a consequence, the devaluation of the peoples whose knowledge systems have been rendered worthless (Cobern & Loving, 2001). That is, the idea that these knowledge traditions are not worth paying attention to, hence their persistent invisibility. First Nations scholar Oscar Kawagley makes the point clear:

A narrow view of science not only diminishes the legitimacy of knowledge derived through generations of naturalistic observation and insight, it simultaneously devalues those cultures which traditionally rely heavily on naturalistic observation and insight. (Kawagley et al., 1998, p. 134, cited by Cobern & Loving, 2001)

Diversity of knowledge, as described, thus may not be sufficient to capture the epistemological implications of recognizing a plurality of knowledges (Visvanathan, 1997, 2005), both for influencing the outcomes of co-creation as well as for making anticipatory design choices (Lee et al., 2018). On the other hand, we completely agree with Lee and her colleagues (2018) on the influence and impact of participants’ knowledge on co-creation, based on their observation that increasing the variety of knowledge “widens the openness of the brief” and contributes “to reframing the purpose” (p. 26). They also note the important influence of the dynamics of the participants and the scope of design on the design of co-creation activities and settings (Lee et al., 2018). One of the challenges that indigenous knowers face in light of the current epistemological infrastructure is how to represent their own knowledge traditions and co-create from their own standpoint (Foley, 2003; Yunkaporta & Shillingsworth, 2020) rather than those imposed on them by the hegemonic knowledge system (Chilisa, 2019; Kuokkanen, 2017; Visvanathan, 2005).

Shiv Visvanathan (2021, 2005) explains the birth of ‘cognitive justice’ (1997), a concept rooted in decolonial thought (Coolsaet, 2016; Rodriguez, 2017), as his response to requests for creating the conditions for equitable exchange of knowledge by an indigenous community of weavers when confronted by a development intervention involving Swedish textile ‘experts’. Their resistance to simply being given “bits of European modern knowledge” (Singh, 2021, p. 1168) rather than being engaged in dialogue on an equal footing led Visvanathan to reframe participation in terms of negotiating the alleged hierarchy of knowledge systems, and thus, the resultant yet hidden power dynamics (Visvanathan, 2005). As Lee et al. (2018) uncover in their analysis, “participant’s interests influence the implementation and impacts of the project results” (p. 28). That is, the outcomes of co-creation-led projects are correlated to the interests of those who hold the power to influence the outcomes of the project, implement them, and leverage them (Lee et al. 2018). For Visvanathan (2005), the presence of the weavers in the form of participation was not enough; they needed cognitive representation as well, by explicit recognition of their own knowledge. Only then would the weaver community be cognitively empowered in meetings with foreign experts (Visvanathan, 2021). Therefore, only when conditions support cognitive representation and cognitive empowerment in addition to participation is cognitive justice realized (Visvanathan, 2005). Cognitive justice advocates for recognition of a plurality of knowledges, and their deep interconnection with livelihoods, lifestyles, and life chances of a people, in addition to creating just and equitable conditions for dialogue (Coolsaet, 2016; Visvanathan, 1997). One can see the importance of cognitive justice even in Lee et al.’s (2018) framework, where distribution of power, diversity of knowledges, and differences in interests have all been identified as influential factors in co-creation processes and outcomes.

This ‘power struggle’ for recognition and respect for indigenous knowledge traditions (see Chilisa, 2019, or Tuhiwai Smith, 1999) is a blind spot unrelated to any particular design research. Lack of its explicit recognition in our processes of knowledge co-construction and co-generation might be due to a lag in design’s epistemological infrastructure against the larger transformation occurring as a result of repositioning the Western knowledge system as only one among a plurality (Cobern & Loving, 2001; Cunningham & Williams, 1993). Interestingly, this line of thought brings us to the Scandinavian tradition of participatory approaches, which distinguish themselves not by their methods but by their political commitment to emancipation and mutual respect for all knowledges (Gregory, 2003), and especially those of workers, i.e., knowledges deeply interconnected with livelihoods and life chances (Visvanathan, 1997). Indigenous knowledges are “constantly engaging with processes of representation and power” (Apgar et al., 2016, p. 57). Epistemological processes which “work with researcher-derived knowledge” and indigenous knowledges are “implicitly embedded within the political struggles of indigenous peoples and peasant communities” (Apgar et al., 2016, p. 57). A decolonial intervention thus may not require any significant changes so much as a deliberated and structured inquiry at the front-end.

An Interface Characterized by Epistemological Plurality

Contemplating the user research potential of a ‘surprise’ is a stance of emergence-friendliness (Gaver et al., 2022; Suchman, 2007). In late 2022, we assumed design research in Indonesia would comprise planning, prototyping, and documenting co-design of an epistemological bridge between indigenous knowledge of disaster preparedness and formal disaster science. The second author suddenly paused while creating a plan for such co-creation and fell silent. This was their moment of surprise, considered an impetus for “emergence-friendly research” (Gaver et al., 2022, p. 3) and defined as “something arising out of ongoing activity, enacted rather than predetermined” (Suchman, 2007, p. 177). As an Indonesian, the second author was struck by the realization that even as a local, they could not proceed without a grasp of the epistemological context within which they aspired to co-design. Secondary research on indigenous knowledges across Indonesia had unearthed ‘local wisdom’ studies (Demolinggo et al., 2020; Hutagalung et al., 2022; Hidayati et al., 2022) but little on the epistemological practices and mechanisms, in contrast to extensive literature from North America, Oceania, and increasingly, Africa. Blomberg and Karasti (2012) encourage us to confront the challenges of co-creation with “the participation of peoples from different knowledge traditions and socio-economic circumstances” (p. 86). As far as we could tell, no means existed by which to map or visualize holistic knowledge and/or hologram structure (Lee et al., 2018). This is where the first author’s experience with extending user research for novel use cases in similar operating conditions (Bhan, 2009a, or Bhan & Gajera, 2018) facilitated methodological development. We would have to combine secondary research, previously tested user research protocols, and begin prototype building from first principles. The first component was the interface where a plurality of knowledge systems would convene for co-creation: the object of design for which user research would be conceptualized to inform.

Research at the Interface

Lin’s (2007) research on Indigenous Taiwanese cultural objects, which “provide an interface” (p. 45) for examining communication through the design of products across boundaries of knowledge systems, proposes a related design process. Lin’s culture product design model inspires design at the interface (e.g., Peng & Chung, 2017; Wang, 2022). Here, we note Lin’s use of the interface to describe the metaphorical space where Indigenous knowledge products communicate with Western theory and practice. Torres Strait Islander man and professor emeritus Martin Nakata theorized a cultural interface where Western and Indigenous knowledge systems intersect to co-exist in highly politicized and contested conditions (1997, 2007a, 2007b, 2010). Nakata’s theory is not merely that of a ‘culture clash’ (Gilroy, 2009); it envisions the interface as a fluid and permeable metaphorical space for ongoing negotiations between Western and non-Western knowledge traditions (Nakata, 2007a). That is, this is the interface:

…where the the trajectories of two different histories, cultures, ideologies and practices intersect, establishing conditions that influence the ways Indigenous people, in both urban and rural regions, make sense of and participate within society. (Gilroy, 2009, p. 45)

It reflects the lived experience of scholars who find themselves interpreting and re-interpreting across boundaries of epistemological plurality (Nakata, 2010; Reano, 2020; Yunkaporta, 2009). As Western-educated, post-colonial Asian designers, each from extremely diverse countries with histories of very different European colonization, Nakata also describes our experience of navigating epistemological plurality. We recognize our own positionality at this interface.

‘Research at the interface’, attributed to Maori scholar Sir Mason Durie (2004, 2005), is an influential approach for epistemologically plural co-creation (Saunders et al., 2024). Durie’s (2005) interface approach respects Indigenous (and other non-Western) epistemologies, axiologies, and cosmologies without subsuming them to the demands of the Euro-Western academy. It is well-suited for designing interfaces for co-creation to accommodate a plurality of knowledges without privileging any one tradition over another. Durie explains its relevance:

…there are an increasing number of indigenous researchers who use the interface between science and indigenous knowledge as a source of inventiveness. They have access to both systems and use the insights and methods of one to enhance the other. In this approach, the focus shifts from proving the superiority of one system over another to identifying opportunities for combining both. (Durie, 2004, p. 1140)

Embracing Durie’s interface approach for planning co-creation will not only recognise plurality, but it expands the notion of ‘diversity of knowledge’ (Lee et al., 2018) to generate new insights from combining two (or more) knowledge systems (Durie, 2004; Nakata, 2010; Yunkaporta, 2019). Nakata’s cultural interface theory promotes a search for common ground and overlaps between what might be incommensurable knowledge traditions, reflecting the rich potential for creativity and innovation (Yunkaporta, 2009:53) when two or more knowledge traditions collaborate at the interface (Durie, 2004).

For example, HCL Hsieh (2014) utilizes the distinction between indigenous cultural products that incorporate profound meaning and design which simply responds to user needs to develop a design pedagogy based on applying “different design methods in order to appropriately transform cultural meaning into design creation” (p. 321). Field study facilitates an emotional connection and re-identification with students’ own traditions. “The whole design creation pedagogical method is [developed] so that they can learn with procedures and steps, instead of randomly creating ideas” (Hsieh, 2014, p. 326). Kun Pyo Lee’s dissertation (2001) is the only study to comparatively evaluate Western-theorized design planning and user research methodology in contexts of epistemological plurality, in this case, those of Japan and South Korea. Professor Lee contributes a mechanism to help choose i) the most appropriate level of innovation, ii) the most suitable design methods, and iii) identify which cultural issues should be focused on during the design process, for any particular context of use (Lee, 2001). He has also conducted comparative studies of user research methods in varying conditions of epistemological plurality (Lee, 2004).

Similarly, Yang and Sung (2016) problematize epistemological plurality in co-creation, although they use the words diversity and multidisciplinarity to describe operating conditions. We conjecture their study conditions may have instantiated a cultural interface. However, one can view their publication as an example of the epistemological blind spot in service design, since not everyone involved in their study may be Western-educated. Duan et al. (2021) provide an explanation for this monolithic view. On the other hand, Yang and Sung (2016) identified service design methods that help with bringing together diverse viewpoints and epistemic backgrounds during co-creation. This highlights an interesting conundrum: service design methods remain useful mechanisms for building bridges across differences in ways of being, doing, and thinking, even though the epistemological infrastructure obscures full recognition of plurality (Duan et al., 2021). It is this agnostic attribute of design methods which we leveraged for our own methodological development. It is not that we need novel methods so much as a renewal of the epistemological infrastructure to refine their use in the change in operating conditions brought about by recognizing a plurality of knowledges (i.e., ‘the new big picture’ of science). Echoes of this conundrum can be found in Leong and Lee (2012) who document Chinese students struggling to grasp Western-theorized concepts such as co-creation. This led them to develop an approach specifically for mainland China (Leong & Lee, 2011). They argue for re-situating exogenously theorized concepts for local, social conditions (Leong & Lee, 2012).

Thus, what we value is the best thinking for a given situation and the wisdom to change one’s thinking when situations change. We advocate epistemological pluralism and the ability to wisely discriminate amongst competing claims. This last point is important because the issues of life typically cross epistemological categories. (Cobern & Loving, 2001, p. 64).

Knowledge systems are socio-political structures (Nakata, 1997; Turnbull, 1997; Turnhout, 2024). We understand knowledge systems “as made up of agents, practices, and institutions that organize the production, transfer and use of knowledge” (Cornell et al., 2013, p. 61). Indigenous and other non-Western knowledge systems struggle for recognition (Odora Hoppers, 2021; Visvanathan, 1997) and remain invisible and unseen (Kuokkanen, 2017), not unlike other invisible social structures that govern heavily institutionalized arrangements (Vink & Koskela-Huotari, 2021), such as the academy. Without grasping the implications of epistemological plurality in advance of initiating co-creation, the blind spot is as likely to have a negative impact on service design outcomes as any other invisible social structure. We therefore extend the timeline of service design materials (Vink & Koskela-Huotari, 2021, p. 30) to include entire knowledge systems (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Vink & Koskela-Huotari’s (2021) timeline of service design materials extended by the authors to include entire knowledge systems.

Here, we also recognize the opportunity for a paradigm-level intervention in the system (Meadows, 1999).

Changing Our Research Paradigm

In conditions of epistemological plurality, it is not simply that knowledge-holders from different knowledge systems acquire status, power, and privilege by means of the relative ranking of their knowledge systems against each other; but all Other knowledges must also jostle for power and status against the hegemonic Western one (Visvanathan, 1997; Mignolo, 2009; Chilisa, 2019; Tuhiwai Smith, 1999). This is the heart of the ‘power struggle’ between entire knowledge systems. Indigenous scholarship on epistemological infrastructures to support just and equitable knowledge co-creation problematizes it as the first step (Chilisa, 2019). How we represent ‘users’ or ‘stakeholders’ or ‘participants’ is an inescapable function of our research paradigm (Chilisa, 2019). That is, does our user research generate a persona of an uneducated farmer helpless in the face of natural disasters (Bankoff, 2001)? Or, do we recognize them as competent knowledge-holders in their own right (Visvanathan, 2005, 2021), and engage with them on their own terms? This is the power imbued in us by our choice of paradigm (Bhan & Vienni-Baptista, 2025). It is made visible by paying “special attention to the power imbalance that exists between the Euro-Western research paradigm and non-Western societies that suffered European colonial rule, indigenous peoples, and historically marginalized communities” (Chilisa, 2019, p. 6).

…the assumption about the vulnerabilities of a certain group made the call to participation an imperative from the design researchers’ perspective. [The] assumption continued throughout the process, despite the fact that the group assumed to be vulnerable was actively pushing back ... This, however, was ignored, as the image of who is vulnerable and in need of empowerment was so strong that it formed the basis of the participatory design project from its very inception. (Björgvinsson & Keshavarz, 2020, p. 248)

Participative approaches are “not evaluated according to a politics of justice and equality demanded and practised by those individuals deemed vulnerable in the first place” (Björgvinsson & Keshavarz, 2020, p. 260). Recognizing “vulnerability” is itself an ideologically motivated and deliberately constructed paradigm (Bankoff, 2001) is the first step. According to Bankoff (2001), the Tropics came to be seen as hazardous through “a systematically constructed paradigm,” and a Western discourse of “vulnerability” began to define the natives (p. 20). Such deficit theorizing and damage-focused assumptions can thus be included among the invisible norms (Vink & Koskela-Huotari, 2021) of the academy. Bringing about purposeful change by co-creation (Lee et al., 2018), therefore, requires us to problematize this power struggle in user research. This means interrogating dominant narratives of user representation as part of inquiry protocols and results of user research.

Indigenous disaster management has been long documented in Indonesia, pre-dating the arrival of Europeans by several centuries (Malawani et al., 2022; Sastrawan, 2022). Newly discovered archival data on a volcanic eruption in 1257 CE provide written evidence, as sources describe recovery strategies in the post-eruption period, including governance strategies, the rebuilding of cities and villages, and agriculture (Malawani et al., 2022). It is a reflection of indigenous’ cultures of disaster’ which were erased by the “systematically constructed paradigm” of colonization (Bankoff, 2001). Volcanic eruptions are portents of Power—political, spiritual, and natural power—and interpreted as omens of political change and divine activity (Sastrawan, 2022). Even now on the island of Java, the Sultan of Yogjakarta appoints a spiritual guardian—the Juru Kunci—for Mount Merapi, one of Indonesia’s most destructive volcanoes. Merapi’s fertile slopes have been inhabited for tens of thousands of years, and they call the volcano Si Mbah, Javanese for ‘respected ancestor’ (or grandfather). Rituals in the region give thanks to Si Mbah for his fertile lands, an integral part of their livelihoods (Sutawidjaja, 2013). For them, volcanic activity is not so much a disaster as part of life with Si Mbah (Sastrawan, 2022).

“Yes, the stories from my grandfather’s time mention that when the volcano erupts, it means Si Mbah is tidying up or building something. It is different for people nowadays. Nowadays, it is called a disaster.” (Interview 5, second round of professional translation)

This realization led us to change our research paradigm for user research. Simply reviewing literature as secondary research would not be enough to represent people on their own terms, as indigenous knowledge-holders in their own right. From Chilisa’s (2019) theorization for indigenous research methodologies, we understand indigenous:

What is indigenous to the majority of people colonized and marginalized by Eurocentric research paradigms? [...] Their ways of seeing reality, ways of knowing, and value systems [which] are informed by their indigenous knowledge systems and shaped by the struggle to resist and survive the assault on their culture. (Chilisa, 2019, p. 10)

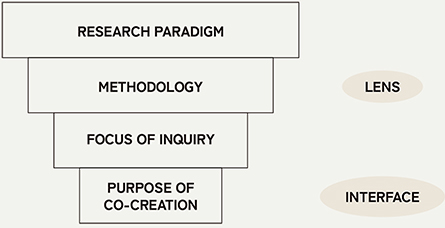

Post-colonial indigenous research paradigms (Chilisa, 2019, 2012) centre “the worldviews of those who have suffered a long history of oppression and marginalization” as they are now “given space to communicate from their frames of reference” (Chilisa, 2012, p. 13). Therefore, we incorporated cognitive justice as the lens to make visible that which dominant paradigms obscured from view. Our deliberated stance for user research now states a) indigenous knowledge of disaster preparedness exists (regardless of dominant narratives rendering it invisible and unrecognized), and b) it is a living tradition of knowledge creation and co-creation, not simply ancestral knowledge products handed down over centuries. Figure 2 summarizes the epistemological logic we arrived at for paradigm change in user research. Our research paradigm drives our methodological implementation, where the lens makes visible what was previously unseen. The focus of inquiry is informed by the co-creation agenda, which will be instantiated at an interface. Such user research would aim to generate actionable insights to inform the design of just and equitable co-creation interfaces in conditions of epistemological plurality.

Figure 2. Epistemological infrastructure for user research by the first author.

Building a Prototype for Field Test

We articulate the aim of our epistemological service design, an inquiry protocol for user research, as a means to deepen our understanding of users’ own indigenous knowledge traditions, thereby conceptualizing a cognitively just instantiation of a cultural interface where co-creation will occur. Building a prototype for testing in real-world conditions is a recognized form of design knowledge production (Stappers, 2007). A holistic human-centered approach for identifying touchpoints in similar operating conditions (Bhan, 2009b) informs prototype design. Turnbull (2009) provides the overarching aim: “an understanding that does not disadvantage indigenous peoples” (p. 2), in line with principles of indigenous research paradigms (Chilisa, 2019).

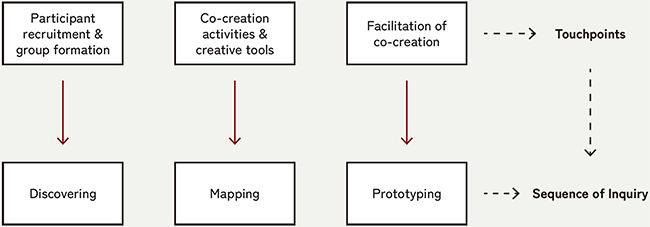

Touchpoints of Co-Creation

For co-creation that will instantiate a cultural interface, three touchpoints are identified as moments in the process of planning and preparation when our epistemic positionality, which informs “what is made relevant pragmatically during communication, related to knowledge” (Singh, 2021, p. 1168) must be clarified and articulated for ensuring cognitive justice in collaborative processes (Bhan & Vienni-Baptista, 2025). This directly relates to the representation of users (e.g., a persona) as one of the key outcomes of user research. Figure 3 summarizes the methodological development of the user research prototype, which builds on previous analyses (Bhan & Vienni-Baptista, 2025; Bhan & Gajera, 2018).

Figure 3. Methodological development of the user research prototype by the first author.

Here, the three touchpoints are correlated to the sequential structure of inquiry. As we saw in Figure 2, the focus of inquiry is informed by the co-creation agenda, for instance, indigenous knowledge of disaster preparedness, as the purpose of co-creation was to build bridges with the disaster science of the authorities (Tedjokusumo, 2023). Methods are therefore not prescribed. Instead, each phase of inquiry ends with a round of analysis that informs the decision to proceed to the next phase; contingent upon the aim of each phase, including Discovering, Mapping, and Prototyping. Thus, a stage-gate ends each phase. Table 1 summarizes the sequential structure of the user research.

Table 1. User research prototype to support the design of the co-creation interface (done by the first author).

| Phase | Touchpoint | Focus area |

| Discovering | Participant selection, recruitment, and group formation | Livelihood and kinship networks, including information and knowledge flows within socio-ecological-economic systems; verifying the existence of relevant knowledge traditions and knowledge-holders (e.g., hologram structure, Lee et al., 2018; or informal traders' value webs, Bhan & Gajera, 2018) |

| Mapping | Agenda of co-creation activities, such as workshops, including custom-designed thinking tools | Mechanisms for cooperation and collaboration, indigenous knowledge traditions, including mechanisms for creating, transmitting, and preserving knowledge across time and space. (Situated practices of local knowledge, Turnbull, 2009) |

| Prototyping | Facilitating the metaphorical cultural interface instantiated by the co-creation project | Iterations or revisions to co-creation sessions, the activities planned, the choice of tools and techniques used, the language and jargon used, facilitator skills and communicative positionality, etc. (Bhan & Vienni-Baptista, 2025). Multiple sites or groups may be used. |

We now describe the implementation of this prototype in Indonesia by the second author.

Phase One: Discovering

Indonesia is spread over 17,000 islands, of which 6,000 are inhabited by more than 3,000 indigenous groups. It is situated in a geologically volatile region known colloquially as the ‘ring of fire’, which makes it prone to natural disasters such as tsunamis, earthquakes, floods, and volcanic eruptions. Discovering in this context of use meant identifying an appropriate and relevant community as representative ‘users’ (Bhan & Gajera, 2018), that is, knowledge-holders of indigenous disaster preparedness knowledge products (Tedjokusumo, 2023). Here, the purpose of co-creation—one of the elements of Lee et al.’s (2018) framework—anchors such open-ended exploratory user research (Bhan, 2009a).

Identifying a community where indigenous knowledge of disaster preparedness was actively a part of daily life required using the snowball method for interviews. The first author interpreted representative sampling in the context of Indonesia’s sprawling diversity and plurality as selecting a handful of residents from three different locations prone to three distinct types of natural hazards. On paper, we prepared a sampling strategy identifying three sites, one each for i) earthquakes, ii) floods, and iii) volcanic eruptions. Much of the early work was done by phone. This created its own challenges for timely referrals and connecting with people. Finally, data was compiled comprising a) telephone interviews with urban residents in two locations with lived experience of periodic flooding, and b) video interviews sampling four rural villages on the slopes of Mount Merapi, one of Indonesia’s most active volcanoes (Tedjokusumo, 2023). Referrals to residents of the earthquake zone fell through. The interviews were conducted by a local contact who emailed the videos with English subtitles for the Javanese dialogue. While it was a friendly effort to be helpful, this approach is not conducive to user research on indigenous knowledge practices. We suggest best practices for operationalizing the translation of indigenous knowledge in the next chapter.

In our initial review across all interviews, we sought knowledge traditions that influence the continued inhabitation of hazard-prone locales. That is, open-ended interviews aimed to discover ‘why didn’t they move?’ from such a hazardous location. This orientation was informed by Sastrawan (2022) on Javanese cultural attitudes to natural hazards, as well as Bankoff’s ‘cultures of disaster’ (2001). Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA, Smith et al., 1999), adapted for Indonesia (Kahija, 2017), was considered suitable for analysis. For instance, Hutagalung et al. (2022) used Kahija’s indigenized IPA for uncovering “local community’s personal attributes contributing to their ability to live and manage their lives successfully” (p.1154) on Mount Merapi.

Our key insight came from the videos, not from the translated transcripts. Tedjokusumo (2023) first experimented with new AI tools, which yielded results indicating that uploaded transcripts consistently summarized high levels of stress and anxiety, regardless of location. The first author is extremely sceptical of AI’s capacity to transcend dominant narratives generated by the legacy of damage-focused assumptions and deficit-laden theorizing. All the Indonesian studies reviewed had described a culture of co-existence with Si Mbah, the grumbling ancestor. Therefore, we decided to review all the videos ourselves, even though neither of us is familiar with the Javanese language. An obvious difference in results between the AI tool and our human eyes and ears was easily spotted: tone of voice and body language, in addition to words, which added nuance missing from the transcripts (Tedjokusumo, 2023). For example, in Interview 1, Merapi’s 2006 eruption is heard being discussed in a very casual tone of voice. In fact, the respondent says, “Oh... that little one,” accompanied by a dismissive wave of the hand. Thereafter, all the interviews were hand-coded, combining review of both text and video (Tedjokusumo, 2023). Analysis revealed that community solidarity, cultural attitudes, and practical wisdom contributed to resilience and disaster response among rural respondents, but not among city dwellers (Tedjokusumo, 2023). These rural results were in line with Hutagalung et al. (2022). This is a cautionary note on the epistemological blind spot and its persistent perpetuation, in this case, through the AI’s own architecture.

These results generated the decision stage-gate in the form of the touchpoint correlated to this phase (Table 1). Selecting the rural residents of Mount Merapi was ideal for the next phase of inquiry. Urban interviews were therefore discarded, and the rural set of transcripts underwent a second round of analysis. In practice, unless travel constraints prevent a second round of interviews, as was the case here, this approach is not advised. Ideally, the first phase generates an exploratory survey dataset from which profiles are identified for Mapping (Table 1). In Bhan and Gajera (2018), the Discovering phase generated 60 interviews sampling a diverse range of actors in the borderland’s informal trade ecosystem, which facilitated informed selection of 8 user profiles after three rounds of analysis for the next phase of mapping. On the other hand, the purpose of this phase of implementing the prototype was clearly and demonstrably achieved (Tedjokusumo, 2023); therefore, user research could proceed to the next phase.

Phase Two: Mapping

For this phase of inquiry, Thematic Analysis was conducted on the rural set of interview transcripts (Tedjokusumo, 2023). Five themes were used for coding, borrowed from Yunkaporta’s (2019) indigenous ways of thinking, which builds on his own research at the interface (Yunkaporta, 2009). To establish the presence of an indigenous knowledge tradition, Kinship was used as the first theme for coding, representing the relational ontology, epistemology, and axiology shared by indigenous knowledge traditions (Chilisa, 2019; Kuokkanen, 2017). Coding for kinship surfaced respondents’ deep connection to Place; their lands, environment, and location (Tedjokusumo, 2023). These deep roots inform community perspectives on disaster preparedness, and the reason why people not only returned to their farms and fields after experiencing multiple evacuations (Interview 2, 3) but also why they did not relocate even though they lived in the shadow of a destructive volcano (see Sastrawan, 2022, for related cultural practices going back a thousand years). Kinship is also reflected in the local name for Mount Merapi: ‘grandfather’ (Si Mbah in Javanese).

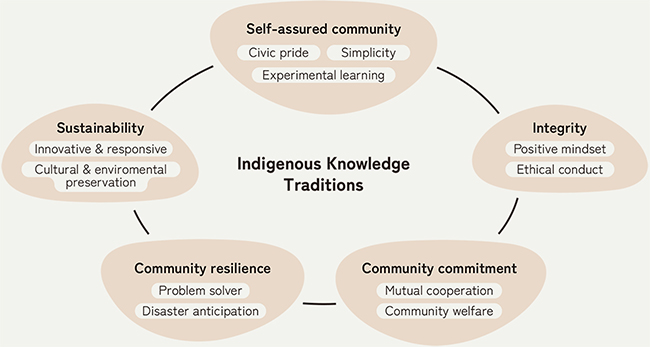

Indigenous knowledge practices for disaster preparedness include converting local knowledge into practical actions (e.g., site selection of a house, Interview 5); pattern recognition over multiple generations (e.g., nature’s signals, multiple interviews); or undertaking rigorous spiritual practice for deep time transmission of co-existence with a volcano (Interview 4, 5). These findings (Tedjokusumo, 2023) align with descriptive studies from Indonesia (e.g., Hidayati et al., 2022) and case studies in Chilisa (2019). At the end of this phase, we were able to clearly identify the central role of indigenous knowledge traditions contributing to community preparedness and resilience. In Figure 4, Hutagalung et al.’s (2022) model of community self-reliance has been adapted to illustrate our understanding. Since the second author could now envision planning co-creation interfaces with the community, we considered this phase to have achieved its purpose.

Figure 4. Authors have adapted Hutagalung et al.’s (2022) model of self-reliance to demonstrate the role of indigenous knowledge traditions.

Phase 3: Manifesting (Prototyping)

Surprise manifested itself again when the second author discovered an existing cultural interface being co-created by community members with the disaster management authorities. An emergence-friendly stance meant adjusting the scope from originally planned prototyping of a co-creation interface to conducting a video-recorded interview instead. Voluntary Search and Rescue Teams (hereinafter referred to as SAR Teams) emerged as a community response (Yulianto, 2021) following the massive eruption in October 2010 (Sutawidjaja, 2013). Headquarters in Yogjakarta plans volunteer monitoring shifts on Merapi and coordinates with regional disaster management and geological agencies (Yulianto, 2021). The second author interviewed them in person, while their local contact recorded on video. According to the SAR Team on duty at their monitoring outpost, Merapi volcano is unpredictable. It was only after the immense losses experienced in 2010 that locals gained more trust in scientific knowledge and technology. Until then, they managed with indigenous knowledge, which had served them well until that ‘once in a lifetime’ eruption that did not follow the pattern of the previous ones (resident interviews).

We [now] use paper maps, which are different from regular maps. We utilize location coordinates. If we use a local resident’s home as a landmark, what if the house is not there? In other words, what if it has melted into the ground?... unlike Google Maps [they] include designated evacuation routes. (SAR Team Interview, second round of professional translation)

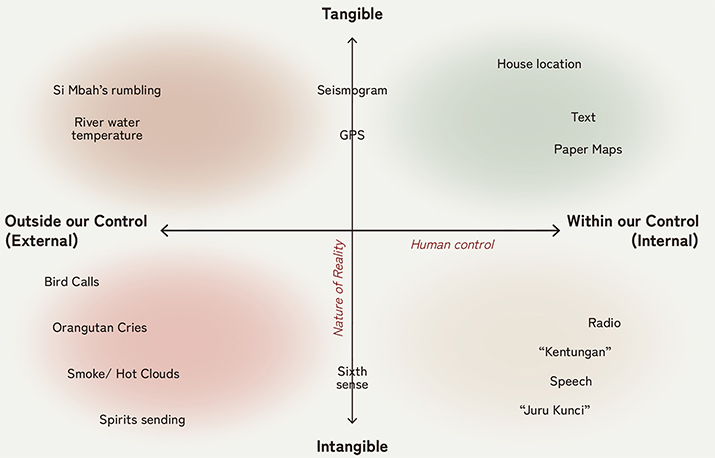

Alerts and warnings based on scientific monitoring turned out to be more accurate due to the lack of natural signals such as hot clouds and rumbling noises (Sutawidjaja, 2013). Figure 5 demonstrates the complexity of the cultural interface being co-created for monitoring and preparedness.

Figure 5. The knowledge products map by the first author visualizes the SAR Team’s co-creation interface.

The position map in Figure 5 uses the axes of epistemology (degree of human control over the knowledge product) and ontology (beliefs on the nature of reality) to visualize the range of signs, signals, communication, and tangible artefacts of design being used to monitor and sense the volcano’s mood and behaviour relative to each other. Plotting all the knowledge products mentioned for preparedness and monitoring on a position map provides a visual snapshot of the cultural interface between indigenous knowledge and modern Western science. We call it a knowledge products map. The SAR Team’s interview provides rich insights on the blending of knowledge products from two different knowledge systems for disaster preparedness, just as Durie describes (2004). The knowledge products map helps visualize epistemological plurality and complexity at the cultural interface instantiated by co-creation. On the other hand, this surprise meant overturning our original plan for this phase, since an indigenously co-created interface was already in existence. The SAR Team’s description of design planning for the co-created service reveals both foresight and indigenous knowledge:

One team is 11 people. One commander, one communication, one as a volunteer who runs. The term running is that if something happens, they can’t communicate, they have to walk or run to contact other people. [Interviewer comment] That’s it, a body system. And six people left. Four people are in charge of help, and the other two to assist, replacing if someone gets tired. That’s our system. It’s impossible for the six to be strong all the time. The rolling backup is for that.[...] Here, SAR is in charge of seven villages....they are under our coordination. They will not move without an order from here. One command, so it won’t be chaotic.[...] Only specific individuals with authorization can access certain areas. The entire coordination process is managed under the supervision of [relevant government agencies]. (SAR Team Interview, second round of professional translation)

The SAR Team’s co-creation is a result of their own traditions rather than any designed intervention. They use the Javanese word pengabdian to describe their motivation; it means devotion. It means night shifts and time spent away from their farms and families in order to safeguard their communities:

Our commitment goes beyond waiting for a mountain eruption. ... If there are accidents, missing people, we actively collaborate with the community to search for and protect them from potential disasters. (SAR Team Interview, second round of professional translation)

Further analysis would therefore initiate planning for any co-creation interfaces with Merapi communities.

Discussion

Implementation of our prototype reveals room for improvement. An experienced practitioner would begin with immersion in the field. Constrained by time and budget, discovery was initiated via phone calls (Tedjokusumo, 2023). However, after a personal visit to Mount Merapi in the third and final phase of inquiry, the second author arrived at this same conclusion. Immersion in the context of the participants and the purpose of co-creation transforms our understanding in subtle ways; a tacit knowledge that does not always translate well into explicit knowledge (Schön, 1995). On the other hand, the first author was able to compensate from experience of user research in ‘different socio-economic circumstances’ (Blomberg & Karasti, 2012). What surprised us was the amount of epistemic labour involved to align fieldwork with post-colonial indigenous research paradigms, particularly during data analysis and interpretation of findings at the end of each stage. We were continuously reviewing indigenous scholars and Indonesian studies. This points to a shift in the locus of our efforts from the practicalities of fieldwork to a focus on methodological coherence and rigour with the paradigm. The principle of accountable responsibility (Chilisa, 2019) requires epistemic investment by service designers and user researchers operating in conditions of epistemological plurality. This also aligns with KP Lee (2001), Leong and Lee (2011, 2012), and Yang and Sung (2012). On the other hand, it also became obvious that knowledge mapping can contribute to nuanced decisions and design choices when using co-creation frameworks (Lee et al., 2018) and canvases (Smeenk, 2023), as well as for implementing interface-sensitive design methods (Hsieh, 2014; Lin, 2007).

For an experiment in changing our research paradigm to one that positions us, epistemologically speaking, at the interface between entire knowledge systems, it was not a failure. In the first phase, Tedjokusumo’s (2023) analysis of the rural set of interviews revealed the contribution of community solidarity, cultural attitudes, and practical wisdom to resilience and disaster response. Although the questionnaire used for the Discovering phase was more open-ended and motivated by a very different over-arching question, these findings aligned with Indonesian scholarship among similar communities in the exact same region (Demolinggo et al., 2020; Hutagalung et al., 2022). The findings from the second phase of inquiry also align our work with a worldwide ‘paradigm shift’ in disaster management from top-down to bottom-up approaches, reflected in Indonesian policy (Hizbaron et al., 2016; Kadir & Nurdin, 2022). Mapping (Table 1) is the phase where we dive into the purpose or aims motivating a co-creation project for which we are doing the user research at the front end. In a study of disaster preparedness of vulnerable communities in the same region, Hizbaron et al. describe the signs used by villagers to alert them to increased risk of eruption: increasingly strong smell of burning sulphur; very rapid heating up; continuous explosive sounds; and very rapid dry skin. They also point to kinship ties for the rapid transmission of this ‘monitoring knowledge’ across the region. The proximity of the village to the peak positions them as an early warning system. Tedjokusumo (2023), the second author, was able to identify both the importance of kinship and nature’s signs for disaster preparedness. In the third and final phase, we were surprised by the existence of an indigenous co-creation interface blending indigenous and Western scientific knowledge products, i.e., the SAR Team. In their study of disaster communication on the slopes of Mount Merapi, Hidayati et al. (2022) spotlight the SAR Team as a critical resource for early warning and describe how loudspeakers, kentongan, and motorcycle horns are used for widespread communication. A kentongan is a traditional bamboo slit drum, and different rhythms communicate different messages, such as ‘be alert’ or ‘gather at the meeting point’ (Hidayati et al., 2022). Our knowledge products map (Figure 5) easily accommodates this combination of traditional and technological devices. Being able to clearly inform decisions at each touchpoint from this sequentially structured inquiry protocol for user research, therefore, encourages us to claim this prototype as proof of concept.

Western-theorized user research methodologies can indeed be extended—by an investment in additional epistemic labour—to problem spaces outside the boundaries of their own knowledge system. The logic of our epistemological infrastructure (Figure 3) held up robustly, where cognitive justice (Coolsaet, 2016; Odora Hoppers, 2021; Visvanathan, 2005) is our lens for inquiry to inform the design of co-creation interfaces guided by purpose and paradigm. Interestingly, ‘surprises’ generated deeper insights on epistemological plurality than any prototype interface we could have developed for such a purpose. This implies knowledge mapping can only be conducted from an ‘emergence-friendly’ (Gaver et al., 2022; Suchman, 2007) stance; no other will work for exploration and discovery in the epistemological blindspot created by coloniality.

Part of inquiring is making judgments about when to be focused and directed and when to be open, receptive. (Marshall, 2001, p. 433)

The sequential structure of this prototype is generative. Stage-gates offer opportunities for real-time iteration of inquiry in response to insights. This helps sharpen focus or accommodate changes, as we did in phase three; both are necessary design choices in open-ended contexts (Lee et al., 2018). This also contributes to the emergence-friendliness of the user research.

Introducing novel paradigms might become “an epistemological battle” (Schön, 1995, p. 32); however, post-colonial indigenous research paradigms (Chilisa, 2019) problematize this very power struggle. That is, it is by changing the research paradigm that we intervene in the epistemological infrastructure (“the system”, Meadows, 1999, p. 19) to address the power and politics known to bedevil co-creation engagements (e.g., see Blomberg & Karasti, 2012). Chilisa (2019, 2017, 2012) deliberately theorizes the post-colonial indigenous research paradigm for valorizing the invisible and the unrecognized. She also argues that it is situated separately and apart from the dominant research paradigms of the Western knowledge system (Klein, 2023, p. 46) and will not be subsumed under any one of them (Chilisa, 2017).

How we represent users influences the design of our entire agenda. Our representation is a function of the research paradigm used for user research. The deliberate re-representation of users as knowledge-holders in their own right, to be engaged with on their own terms (Bhan & Vienni-Baptista, 2025), as advocated by cognitive justice (Visvanathan, 1997, 2005, 2021), opens the doors to ‘research at the interface’ (Durie, 2004, 2005). Such decolonial interventions in our epistemological infrastructure encourage us to conclude that knowledge mapping, while not prescriptive, is instead a robustly theorized structure for user research at the front end of co-creation in conditions of epistemological plurality. The sequence of inquiries is derived from touchpoints, which act as a navigational guide for exploration and discovery in novel terrains. Service design in conditions of plurality is not new; however, knowledge systems themselves need to be recognized for their role in co-creation and its outcomes.

Insights for Practitioners

Our proof of concept encourages us to contribute these insights for praxis.

Respect and Recognition of Different Ways of Knowing (Cognitive Justice)

We emphasize the importance of respecting and recognizing all stakeholders to be involved in co-creation projects as knowledge-holders in their own right. By resisting the notion of privileging scientific knowledge over other ways of knowing, cognitive justice advocates for all forms of knowledge to be equally valued and represented. When all stakeholders stand equally as knowledge-holders in the collaboration, it also minimizes expert bias and groupthink.

Sensitizing Professionally Trained Translators

Professional translator training prioritizes scientific precision and textbook English, potentially eroding indigenous wisdom or erasing knowledge products altogether. To address this, a thorough briefing and sensitivity training for translators is essential to preserve cultural authenticity. This results in transcripts that may not be grammatically correct in English, but more sensitively represent people’s words and knowledge products. Only by commissioning a second round of translation were we able to surface the indigenous concept of ‘wedhus gembel’ (dirty sheep). It is the local name for ‘pyroclastic flows’, the geological name for poisonous hot clouds that signal volcanic eruption. Seeing farmers discuss ‘pyroclastic flows’ in interviews surprised us enough to delve deeper into the processes of professional translation and uncover the erasure of indigenous knowledge. We highlight this as a crucial part of just and equitable co-creation.

Rich Media User Research Documentation

The richness of data obtained through note-taking may be significantly less than that captured by video. Additionally, interviewer notes may introduce bias, potentially leading to the loss of details and nuances. Viewing the videos, along with the translator’s transcripts, helped surface nuances embedded in tone of voice and body language. This becomes more important when the researcher is unable to conduct interviews in person. Using video minimizes the risks of losing valuable information and nuance during data transfer between team members.

Human-Led Analysis

Experimentation with AI tools for qualitative data analysis revealed limitations. The text-based input for analysis yielded a notable disparity in the generated codes (Tedjokusumo, 2023), underscoring the absence of rich media analysis as described above. The lack of emotional, social, and cultural context in the AI-generated analysis also highlights the importance of engaging in self-coding and verifying against other indigenous sources and literature. This is particularly important when we aim to bridge the epistemological blind spot in legacy data and change our research paradigm.

Concluding Remarks

...all knowledge traditions are spatial in that they link people, sites, and skills. (Turnbull, 1997, p. 551)

In our view, knowledge generates maps. A relational map visualizes the flows of knowledge and information between and among people in their socio-economic ecosystem, alongside their exchange of goods, services, and money (Bhan & Gajera, 2018). In this study, we mapped knowledge products (Figure 5) from more than one knowledge system relative to each other on the axes of epistemology (degree of human control over knowledge products) and ontology (beliefs on the nature of reality) to visualize Nakata’s (2007a) metaphorical cultural interface where co-creation will occur in conditions of epistemological plurality. We can also map patterns of creating, transmitting, and preserving knowledge within and between generations as the second author does (Tedjokusumo, 2023). Alternatively, as is the case in the continent called Australia, the natural landscape itself is a knowledge map where sites and stories have intertwined for millennia into songlines (Yunkaporta & Shillingsworth, 2020).

Embracing the notion of entire knowledge systems as materials for service design opens doors for developing user research as a form of epistemologically sensitive service design for facilitating inclusion of “participants from different knowledge traditions” (Blomberg & Karasti, 2012, p. 107) in the pan-disciplinary processes of co-creation. Thinking of entire knowledge systems as design materials also generates such interesting questions as what would be revealed by a paradigm mapping exercise with interdisciplinary teams of researchers in a European university? And could such epistemologically sensitive service design research generate knowledge products to facilitate co-creation at the interface of increasingly thin boundaries between disciplines and knowledge traditions? These questions and more are top of mind for facilitating collaborative knowledge production, securing the future of our planetary home.

Acknowledgments

We thank Indonesian geologist William Kwan for conducting the first round of interviews on Mount Merapi and for serving as a guide during fieldwork for the second author. We are grateful to communities that welcomed us and were willing to share their memories of traumatic experiences. We appreciate the editorial support we have received in the development journey of this knowledge product, guided by the comments of the two anonymous reviewers.

References

- Apgar, J. M., Mustonen, T., Lovera, S., & Lovera, M. (2016). Moving beyond co-construction of knowledge to enable self-determination. IDS Bulletin, 47(6), 55-72. https://doi.org/10.19088/1968-2016.199

- Bankoff, G. (2001). Rendering the world unsafe: ‘Vulnerability’ as Western discourse. Disasters, 25(1), 19-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7717.00159

- Baulenas, E., Bojovic, D., Urquiza, D., Terrado, M., Pickard, S., González, N., & Clair, A. S. (2023). User selection and engagement for climate services coproduction. Weather, Climate, and Society, 15(2), 381-392. https://doi.org/10.1175/wcas-d-22-0112.1

- Bhan, N. (2009a). Understanding BoP household financial management through exploratory design research in rural Philippines and India: Insights to help improve success rate of business models and payment plans for irregular income streams [Report]. The iBoP Asia Project (IDRC) Ateneo de Manila University.

- Bhan, N. (2009b, January 5). The 5Ds of BoP marketing: Touchpoints for a holistic human-centered strategy. Core77. https://www.core77.com/posts/12233/The-5Ds-of-BoP-Marketing-Touchpoints-for-a-holistic-human-centered-strategy

- Bhan, N. & Gajera, R. (2018). Identifying the user in an informal trade ecosystem. In Proceedings of Design Research Society conference on design as a catalyst for change (pp. 1010-1022). DRS. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2018.674

- Bhan, N., & Vienni-Baptista, B. (2025, June 4-6). Relational knowledge inquiry at the front-end of co-creation to facilitate transformation [Paper presentation]. The 47th Association for Interdisciplinary Studies Conference, Oulu, Finland. https://eventos3-202b6.kxcdn.com/uploads/498/materials/6cb90c12ea10a8902dd0fc0f34cbe386.pdf

- Björgvinsson, E., & Keshavarz, M. (2020). Partitioning vulnerabilities: On the paradoxes of participatory design in the city of Malmö. In A. Dancus, M. Hyvönen, & M. Karlsson (Eds.), Vulnerability in Scandinavian art and culture (pp. 247-266). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37382-5_12

- Blomberg, J., & Karasti, H. (2012). Ethnography: Positioning ethnography within participatory design. In J. Simonsen & T. Robertson (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of participatory design (pp. 86-116). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203108543.ch5

- Buchanan, R. (2001). Design research and the new learning. Design Issues, 17(4), 3-23. https://doi.org/10.1162/07479360152681056

- Castro-Gómez, S. (2021). Zero-point hubris: Science, race, and enlightenment in eighteenth-century Latin America. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9798881816308

- Chilisa, B. (2012). Indigenous research methodologies (1st ed.). Sage.

- Chilisa, B. (2017). Decolonising transdisciplinary research approaches: An African perspective for enhancing knowledge integration in sustainability science. Sustainability Science, 12(5), 813-827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0461-1

- Chilisa, B. (2019). Indigenous research methodologies (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Cobern, W. W., & Loving, C. C. (2001). Defining “science” in a multicultural world: Implications for science education. Science Education, 85(1), 50-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-237X(200101)85:1<50::AID-SCE5>3.0.CO;2-G

- Coolsaet, B. (2016). Towards an agroecology of knowledges: Recognition, cognitive justice and farmers’ autonomy in France. Journal of Rural Studies, 47(part A), 165-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.07.012

- Cornell, S., Berkhout, F., Tuinstra, W., Tàbara, J. D., Jäger, J., Chabay, I., De Wit, B., Langlais, R., Mills, D., Moll, P., Otto, I. M., Petersen, A., Pohl, C., & van Kerkhoff, L. (2013). Opening up knowledge systems for better responses to global environmental change. Environmental Science & Policy, 28, 60-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.11.008

- Cross, N. (1997). Descriptive models of creative design: Application to an example. Design Studies, 18(4), 427-440. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0142-694x(97)00010-0

- Cunningham, A., & Williams, P. (1993). De-centring the ‘big picture’: The origins of modern science and the modern origins of science. The British Journal for the History of Science, 26(4), 407-432. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007087400031447

- Demolinggo, R. H., Damanik, D., Wiweka, K., & Adnyana, P. P. (2020). Sustainable tourist villages management based on javanese local wisdom. International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Reviews, 7(2), 41-53. https://doi.org/10.18510/ijthr.2020.725

- Dorst, K., & Cross, N. (2001). Creativity in the design process: Co-evolution of problem–solution. Design Studies, 22(5), 425-437. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0142-694x(01)00009-6

- Du Plessis, H., & Raza, G. (2004). Indigenous culture as a knowledge system. Tydskrif vir Letterkunde, 41(2), 85-98. https://doi.org/10.4314/tvl.v41i2.29676

- Duan, Z. (2024). Soiling service design: Situating professional designing among plural practices. [Doctoral dissertation, The Oslo School of Architecture and Design]. Norwegian Research Information Repository. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/3119436

- Duan, Z., Vink, J., & Clatworthy, S. (2021). Narrating service design to account for cultural plurality. International Journal of Design, 15(3), 11-28. https://doi.org/10.57698/v15i3.02

- Durie, M. (2004). Understanding health and illness: Research at the interface between science & indigenous knowledge. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(5), 1138-1143. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh250

- Durie, M. (2005). Indigenous knowledge within a global knowledge system. Higher Education Policy, 18, 301-312. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300092

- Duxbury, N., & Garrett-Petts, W. F. (2024). Re-situating participatory cultural mapping as community-centred work. In T. Rossetto & L. L. Presti (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of cartographic humanities (pp. 329-338). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003327578-42

- Duxbury, N., Garrett-Petts, W. F., & MacLennan, D. (Eds.). (2015). Cultural mapping as cultural inquiry. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315743066-1

- Ferreira, I., Lupp, G., & Mahmoud, I. (Eds.). (2023). Guidelines for co-creation and co-governance of nature-based solutions: Insights from EU-funded projects. European Commission.

- Foley, D. (2003). Indigenous epistemology and Indigenous standpoint theory. Social Alternatives, 22(1), 44-52.

- Gaver, W., Krogh, P. G., Boucher, A., & Chatting, D. (2022). Emergence as a feature of practice-based design research. In Proceedings of the conference on designing interactive systems (pp. 517-526). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3532106.3533524

- Gregory, J. (2003). Scandinavian approaches to participatory design. International Journal of Engineering Education, 19(1), 62-74.

- Gilroy, J. (2009). The theory of the cultural interface and indigenous people with disabilities in New South Wales. Balayi, 10, 44-58.

- Henriksen, D. (2016). The rise in co-authorship in the social sciences (1980–2013). Scientometrics, 107(2), 455-476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1849-x

- Hidayati, U., Widiarti, P. W., & Nugroho, E. P. (2022). Disaster communication of the Merapi slope community. Informasi, 51(2), 267-280.

- Hizbaron, D. R., Iffani, M., & Wijayanti, H. (2016). Disaster management practice towards diverse vulnerable groups in Yogyakarta. In Proceedings of the 1st international conference on geography and education (pp. 7-12). Atlantis Press.

- Hsieh, H. C. L. (2014). Integrating Taiwanese culture into design pedagogy. International Journal of Education Through Art, 10(3), 317-329. https://doi.org/10.1386/eta.10.3.317_1

- Höök, K., & Löwgren, J. (2012). Strong concepts: Intermediate-level knowledge in interaction design research. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 19(3), Article 23. https://doi.org/10.1145/2362364.2362371

- Hutagalung, H., Purwana, D., Suhud, U., Mukminin, A., Hamidah, H., & Rahayu, N. (2022). Community self-reliance of rural tourism in Indonesia: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Report, 27(7), 1151-1168. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5215

- Jacob, F. (2001). From night bustle to printed quietness. Treballs de la Societat Catalana de Biologia, 51, 11-13. https://publicacions.iec.cat/repository/pdf/00000027/00000055.pdf

- Jacobi, J., Llanque, A., Mukhovi, S. M., Birachi, E., von Groote, P., Eschen, R., Hilber-Schöb, I., Kiba, D. I., Frossard, E., & Robledo-Abad, C. (2022). Transdisciplinary co-creation increases the utilization of knowledge from sustainable development research. Environmental Science & Policy, 129, 107-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.12.017

- Jakab, M., Kittl, E., & Kiesslich, T. (2024). How many authors are (too) many? A retrospective, descriptive analysis of authorship in biomedical publications. Scientometrics, 129(3), 1299-1328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-04928-1