Why Your Storage is Always Full: Identifying Design Opportunities to Support Divestment of Households’ Unused Products

Karin Nilsson *, Helena Strömberg, and Oskar Rexfelt

Chalmers University of Technology, Göteborg, Sweden

This study explores which unused products are retained in households and discusses design opportunities to facilitate their divestment, bringing them back into use. Exploratory visits to 20 households were conducted, each comprising a sensitizing activity, an interview, and a tour of the households’ storage. The study revealed various types of unused products retained in the households; products with potential utility, products with emotional significance, and those that were unwanted by the household. Three key factors driving the retention of these products were identified. First, many households retained items due to the perceived product benefits, hoping they would be useful again in the future. Second, the divestment conscience, the consumers’ apparent desire to ‘do the right thing’ with a product, made it challenging to divest certain products as households struggled to find a satisfactory way to do so. Overall, the perceived effort required to divest products, the perception of divestment work, emerged as a major barrier, influencing all divestment scenarios. The paper discusses the opportunities for design to address these factors, to support divestment of the various types of unused products in households.

Keywords – Circular Economy, Design for Divestment, Household Visits, Product Attachment, Product Retention.

Relevance to Design Practice – This research presents in-depth descriptions of people’s motivations for retaining unused products within their homes. Three factors influencing product retention are presented to guide designers in addressing various drivers of product retention. Further, the article highlights opportunities for future design research in relevant areas regarding product divestment.

Citation: Nilsson, K., Strömberg, H., & Rexfelt, O. (2025). Why your storage is always full: Identifying design opportunities to support divestment of households’ unused products. International Journal of Design, 19(1), 95-108. https://doi.org/10.57698/v19i1.06

Received May 17, 2024; Accepted March 13, 2025; Published April 30, 2025.

Copyright: © 2025 Nilsson, Strömberg, & Rexfelt. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: nikarin@chalmers.se

Karin Nilsson is a Ph.D. student in the Division of Design & Human Factors at Chalmers University of Technology. She researches how design can support product reuse and circular consumption practices. By employing designerly methods, such as artifacts and prototypes, she explores possible future scenarios and investigates how design can facilitate a shift towards a desired and sustainable future.

Helena Strömberg has a Ph.D. in Human-Technology-Design and is an associate professor at the Division of Design & Human Factors at Chalmers University of Technology. She researches the role that design can play in creating the preconditions for sustainable everyday activities within mobility, consumption, and household energy use.

Oskar Rexfelt is an associate professor at the Division of Design & Human Factors at the Chalmers University of Technology. His research considers the development of user-centered products and services. With his research, he aims to develop methodological support for designing usable solutions that benefit the customer. He also researches consumer acceptance and the adoption of sustainable consumption patterns.

Introduction

Circulating products at their highest value is central to the circular economy (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, n.d.) thus mitigating the strain of consumption on natural resources. There are multiple ways of ensuring that a product’s value can be recovered as a part of a circular economy. These range from strategies to increase product lifetimes by encouraging users to use their products longer to ensure the reuse of products by passing products on to new users once they do not fill their purpose with their first user, and finally recovering the material once the product becomes obsolete beyond reuse.

Despite the potential benefits, challenges persist in transitioning products into reuse. The rise in storage units and increased popularity of home organization are indicative of the difficulties experienced in the disposal of the things households no longer use (Cwerner & Metcalfe, 2003; Dommer & Winterich, 2021). Products appear to be purchased and used only a handful of times before moving into storage for much of their lifetime (Conde et al., 2022), often being retained in the peripheral spaces in households, rather than recirculated (Cwerner & Metcalfe, 2003; Gregson et al., 2007a). In a Swedish context, it appears that a substantial number of unused products are retained in the household, as 83% of households reported that they had products at home that were no longer being used and 7 out of 10 households used half or even less of the things kept in their storage (Myrorna, 2018). This apparent surplus of unused products represents a potential resource for the circular economy if the products could be awakened from their in-storage hibernation and become used again.

Divestment is a concept describing peoples’ separation from their things (Gregson et al., 2007b). This phase of the consumption process has not been as extensively studied compared to the acquisition or use of products. Those who have studied divestment have identified two subprocesses, disposition which is concerned with the physical disposal of products and detachment which concerns the emotional and mental separation from a product (Poppelaars et al., 2020), where both are important for products to be divested. The divestment process ultimately leads to a decision to either retain or dispose of the product (Dommer & Winterich, 2021; Jacoby et al., 1977), opening different paths through which the product can be circulated within or outside of the household. From a sustainability perspective, many of the unused products kept in households would benefit from being divested rather than retained in order to enable the reuse of the product.

Increasing the Utilization of Products

In their typology of key concepts for product design in the circular economy den Hollander et al. (2017) propose that product lifetimes should be understood in relation to obsolescence, where a product is considered obsolete when its owner no longer considers it useful or significant. To counteract obsolescence, design for attachment has emerged as a strategy within sustainable design, aiming to reduce consumers’ tendencies to replace products, and thus extend product lifetimes and increase their utilization (e.g., Chapman, 2009; Mugge et al., 2005; Page, 2014; Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008; van den Berge et al., 2021).

Product attachment has been defined as the emotional bond a consumer experiences with a product (Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008). Mugge et al. (2005) suggest that long-lasting relationships between a person and a product arise from its perceived irreplaceability. This can be achieved by designing for superior utility, aesthetics, symbolic meanings, memories, or personalization. van den Berge et al. (2021) highlight strategies to encourage retention over replacement, such as designing for attachment, aesthetics, care, and upgradeability. Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim (2008) find that enjoyment and memories are key factors influencing whether a consumer keeps or disposes of a product, suggesting that designers should prioritize these aspects. Page (2014) similarly notes that memories, pleasure, and usability are central to product attachment, urging designers to foster positive associations and pleasurable experiences through material qualities. Verbeek and Crease (2005) introduce the concept of “cultural durability,” emphasizing strong bonds between people and products through design strategies like gracefully aging materials and repairability. Further, Orth et al. (2018) stress the need for designers to consider both the importance and authenticity of the associations people form with an object.

These design approaches thus aim to address premature replacement and throwing away of products and reduce the current ‘throwaway culture’ (Page, 2014). However, the utilization of products could also be increased by supporting the circulation of products between consumers so that more people can utilize each item. This approach has received attention in circular economy literature, as authors suggest design strategies such as designing for reuse, repair, refurbishment and remanufacturing (den Hollander et al., 2017; Go et al., 2015; Parchomenko et al., 2023).

The unused products that pile up in people’s storages, as described in the introduction, are of course a problem in terms of their utilization (Cwerner & Metcalfe, 2003; Gregson et al., 2007b; Sarigöllü et al., 2021). These products are not used by their owners, nor are they being circulated to be used in new households. In relation to such retention behaviors, people’s attachment to products can be a contributing factor (Dommer & Winterich, 2021; Kowalski & Yoon, 2022). Attachment caused by the experienced irreplaceability of a product may lead to passive use and redundant consumption, as the irreplaceable product transitions to decorative use or storage to protect the product, and new products are introduced to satisfy its former practical functions (Kowalski & Yoon, 2022). Consequently, the design for attachment poses a risk of diminishing active product lifetimes, as it can impede the active use of products and hinder the divestment of products that are no longer used in the household.

To enhance the utilization of unused products, it is crucial to support consumers in divesting them. However, research on consumer behavior regarding product retention and divestment is limited. While the literature on product attachment explains why products are retained due to their functional and emotional value, it does not provide a complete picture, as it mainly focuses on the distinction between keeping or replacing a product. Studies specifically addressing the retention of unused products are scarcer. Sarigöllü et al. (2021) offer valuable insights into product retention, concluding that attachment can indeed cause retention, and that product quality and monetary value increase the likelihood of a product being resold. They also find that aversion to unused utility is the most important driver of product redistribution. However, people who want to avoid waste often retain products instead of selling or discarding them. This study relies on self-reported consumer intentions, which may not capture additional everyday factors influencing behavior and may overlook the often unintentional process of products being stored away unused (Suarez et al., 2016). Simpson et al. (2019) present several reasons for product retention, focusing on scenarios where personal computers (used or unused) are returned to companies. They, like Sarigöllü et al. (2021), discuss that a feeling of emotional reward can affect divestment, e.g., knowing that a product can reach someone who needs it more can make it easier to let go.

Concrete guidance on how to design for divestment is even more scarce. One notable contribution is the ten design principles for the divestment of mobile phones presented by Poppelaars et al. (2020), which offer advice on supporting phone users at various stages of the divestment process. While these principles may be applicable to other types of products, they still target a single product type and its specific conditions. Another study focusing on a particular product category is Clawson et al. (2015), which investigated Craigslist advertisements for personal health tracking technology products. A key piece of advice from that study is that designers should design for “happy abandonment” and be aware that consumers might stop using a fitness product once they have reached their goals or if their life situation changes. Thus, it is important for designers to understand their users throughout the entire use cycle.

To conclude, the literature specifically focusing on why unused products are retained in storage rather than circulated is limited. While some notable examples exist and contributions from areas such as product attachment are valuable, this phenomenon is not fully explored. Additionally, how this retention problem can be addressed through design is even less researched. Therefore, this paper seeks to contribute additional knowledge to help designers support the divestment of unused household products. We achieve this by visiting households, investigating which unused products are retained, and exploring why they have not been divested. By uncovering consumers’ experienced barriers to divestment for different types of products, we can highlight opportunities for designers to address these obstacles and encourage more efficient product circulation and utilization.

Method

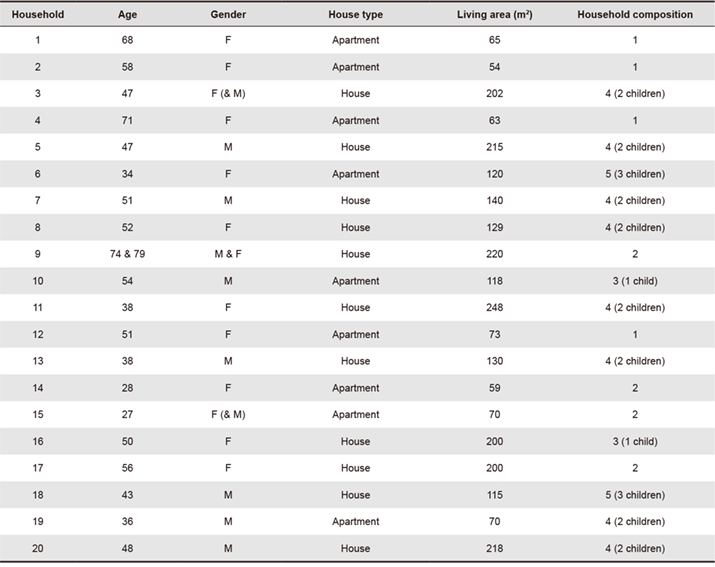

To identify which unused products are retained in households and understand the reasons for their retention, exploratory visits in Swedish households were conducted. Twenty households were visited during the study (Table 1), and 23 participants partook in the activities of the visits. These activities comprised three parts: (1) a sensitizing exercise that the participants carried out before being visited by the researchers, (2) a household visit where one (sometimes two) of the homeowners were interviewed, followed by (3) a household tour where the homeowner(s) and the researchers explored the households’ storages and unused products. The participants came from a variety of households, some from single households and others from households with up to five family members. Their housing ranged from smaller and more centrally located apartments to bigger suburban houses, as well as countryside houses with significant storage capacity.

Table 1. Participating households.

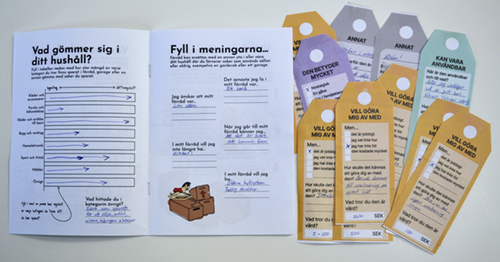

During the sensitizing exercise (Sleeswijk Visser et al., 2005), participants were asked to fill out a booklet and tag unused products in their households to prepare them for the upcoming visit by the researchers. See an example of a filled-out booklet and tags in Figure 1. In the booklet, participants provided basic household data, but the booklet also included tasks where participants were, for example, asked to estimate the character and quantity of unused products that they kept and where they were stored.

Figure 1. Booklet and tags, an example from household P13.

Participants were asked to use the tags that accompanied the booklet to mark unused products found in their households. Four types of tags were included; tags for meaningful products, tags for useful products, tags for products they wished to get rid of, and tags for other products that did not fit the previous categories. When the tag was attached to an unused product, participants were also asked to, on the tag, note the reason for why the product was retained, how they would feel if they got rid of it, and to estimate the market value of the product.

The household visits themselves commenced with a semi-structured interview, focusing partly on the answers in the booklet the participant had completed beforehand and partly on additional questions in a prepared interview guide. This guide contained questions on different themes regarding unused products and the household’s practices of storing said products while also allowing for additional questions depending on the progression of the interview.

During the visit, participants were also asked to show and talk about which products they had tagged in the sensitizing activity. This often coincided with a tour of one or more storage areas in the household where the unused products had been located. This was done to get a deeper understanding of the motivations for retaining the product and the participants’ thoughts about the future for the products. All tags were collected, and the marked products were photographed for reference.

For the analysis, all tagged, unused products were categorized using COICOP categories (United Nations, 2018), to provide an overview of the types of products identified in the study. The interviews were transcribed in full and uploaded to Atlas.ti for analysis. Using Atlas.ti, the interviews were coded and grouped into themes following a thematic analysis structure (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to find patterns in why the products had been retained within the home. An iterative coding approach was employed, wherein the set of codes was continuously refined throughout the coding process. This refinement occurred through discussions among the three coding researchers aimed at optimizing the code framework to best capture the diverse factors influencing product retention. The researchers first coded two interviews each and then synthesized their codes into a shared set of codes. This set was then used to code two more interviews per researcher, after which the researchers decided on a basic coding structure used for the remainder of the interviews. The set of codes then continuously underwent minor refinements (some were reworded, some were combined, etc.) as the researcher’s understanding of the major causes for product retainment developed. Given the exploratory nature of the research, the coding process did not aim for formal data saturation. Instead, the focus was on capturing a broad and diverse range of insights, and the iterative coding approach ensured that the coding framework remained flexible enough to incorporate new patterns as they emerged.

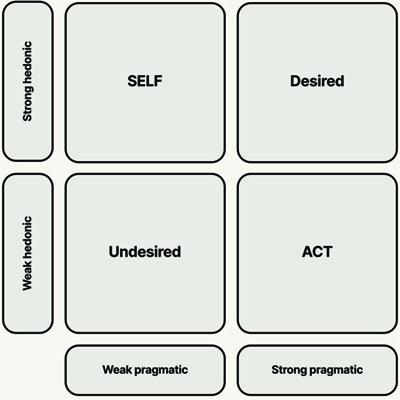

To enhance the analysis of the connection between individuals and products, Hassenzahl’s (2003) concept of ‘apparent product character’ was employed. The authors have in the past fruitfully used this concept to analyze retained products in a smaller study (Nilsson et al., 2023). Hassenzahl posits that individuals shape the apparent product character by considering the product’s features in conjunction with their own expectations. This concept encapsulates their unique personal encounter with the product, influencing emotions, behaviors, and judgments of its appeal. The character encompasses pragmatic attributes, reflecting the perceived ability of the product to aid in achieving user behavioral goals, and hedonic attributes, emphasizing psychological well-being through, e.g., stimulating communication of identity and evocation of valued memories. Additionally, the perception of these attributes can vary in strength, leading to the creation of four distinct product characters: Unwanted, SELF, Desired, and ACT (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Representation of the apparent product character model, adapted from Hassenzahl (2003).

The participants’ stories of why they had retained their products were sorted into the apparent product character model, utilizing the patterns uncovered in the coding. Each story could be connected to either SELF, ACT, or Unwanted product characters. The data contained no story linked to the Desired product character, probably because products with this character are in active use or at least not considered unused. This sorting made it possible to deepen the analysis by focusing separately on stories related to strong hedonic attributes (the SELF quadrant), strong pragmatic attributes (the ACT quadrant), and weak attributes overall (the Unwanted quadrant).

Findings: Unused Products in the Household

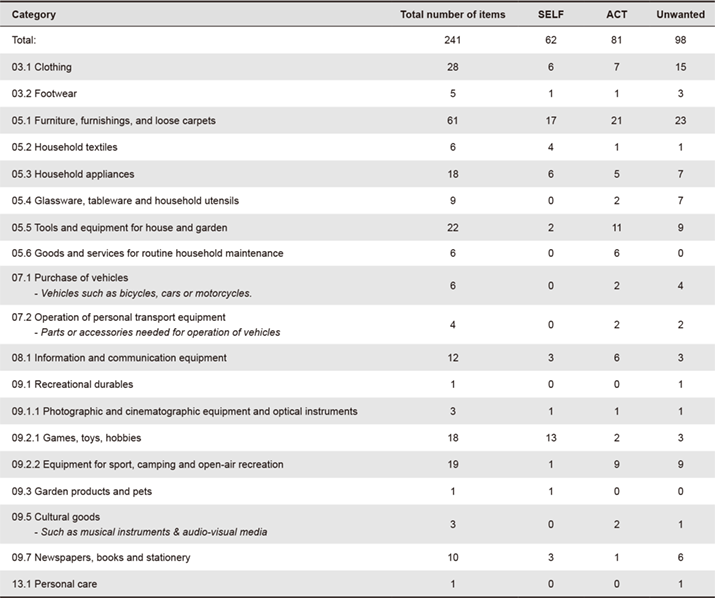

A total of 241 unused products were selected and tagged by the participants and thus discussed in the interview study. Most of the unused products were found in the categories of clothing, furniture and furnishings, tools and equipment for house and garden, games, toys, and hobbies, as well as sporting and camping equipment (see Table 2). While many products were retained for their emotional significance to their owner or for their potential utility, more than a third of the unused products were tagged as unwanted by the households.

Table 2. Tagged products divided by product category (COICOP) and character.

The interviews highlighted a variety of motivations for retaining a product, either due to its significance to the owner or due to experienced or expected difficulties in the disposition process. For all the tagged products, participants provided rich descriptions of the product’s story, how they connected to it, and how they saw its future. In the following sections, these stories are presented linked to why the products had been retained within households, categorised according to apparent product character: SELF, ACT, and Unwanted.

SELF—Products Retained Due to Ideals, Memories, and Relationships

Several of the unused products tagged by the participants had been retained due to their emotional significance to their owners. These products mainly belonged to the category furniture, furnishings, and loose carpets, but also the category games, toys, and hobbies (see Table 2). In participants’ stories related to these products, nuanced reasons for their retention could be distinguished.

One common reason was nostalgic value, especially in the category of games and toys. These nostalgic products especially carried with them memories from childhood and growing up. One participant, for example, showed her collection of Barbie dolls and clothing, saying:

It is childhood memories. It is saved for my future grandchildren. I thought it was fun when I was a child. These are Barbie clothes that were given to me by my cousins when I was little. They will never be thrown away, no, never, even if they fall apart. (P2)

The items thus represented both own memories, as well as past and future relationships; they could not be divested. The difficulty in divesting similar products was something many participants had reflected on during the sensitizing activity. One participant felt they needed permission to get rid of nostalgic products, asking herself, “are you allowed to? […] You kind of separate yourself from your childhood and your family, or your parents, if you throw away the things that are memories from then” (P8), and another had to try and convince himself “it’s actually not anything more than stuff” (P5) to be able to let go of the nostalgia.

Building on the connection between products and relationships, another reason for retaining products in this category was that they were inherited. These products, often furniture or tableware, were emotionally significant to the participants as they embodied memories of relatives or loved ones. For example, one participant (P19) mentioned a set of paintings inherited from his grandmother. The paintings depicted the area where his father grew up, and he could recall the paintings hung in his grandmother’s house during his childhood. He had, however, not hung the paintings in his own home, noting that he would not even have looked twice at the paintings if he came across them in a second-hand shop. He still could not get rid of them as it felt so callous; “like erasing a part of that person and those memories” (P19). This tension between emotional attachment to inherited products and the lacking desire to actually use them was apparent for many of the unused but retained products in the study.

Another aspect often mentioned regarding inherited or gifted products was a sense of responsibility to take care of the products. Participants mentioned feelings of betrayal triggered by the thought of getting rid of such products, even if they would not miss the product itself. Participant 16 hardly dared use the crocheted blanket gifted from her aunt, but she felt that “to put it up for sale at a flea market would be a betrayal and mockery of her work”. Another participant recognizes that his relatives probably would not have cared if he got rid of the things they thought were valuable, but that now had lost their relevance and noted, “maybe it’s that sentimental barrier that’s the toughest” (P10). Products’ embodiment of memories and relationships are a strong barrier for divestment for many of the unused products found in households even though the product remains in storage rather than being used.

For inherited products, it appears as if the attachment to the product is handed down through the generations along with the product. For the inherited paintings mentioned above, P19 stated feeling responsible for coming generations to steward the paintings. Several participants mentioned products, mainly kitchen and tableware, from previous generations that they had kept in storage for their children to inherit when moving out. They saw this as an opportunity to furnish their children’s new households without having to purchase new products. However, this did not always work out, as “you save a lot and then when it’s time for them to move they don’t want it anyway” (P10). Participant 8 reflected on what is worth saving when finding an unused soup terrine with a note from her great grandmother that her parents had saved:

For whom [do we save]? Maybe the sentimental value isn’t there for us anymore? [...] For me some things are important to save from my childhood, but maybe not for my children.

The emotional significance of these products, and that the next generation or other people did not value them equally, created friction for the participants in the divestment process. While they themselves had never used the full sets of china that they had inherited, and the next generation had said ‘we have enough’ when asked whether they would like them, household 9 still thought it would be a shame to sell them cheaply at a second-hand shop, so they preferred to retain them. Another household (3) went so far as to saw apart a piece of inherited furniture instead of selling it, as he felt his grandfather’s chair could not be valued in the same way by someone else.

In summary, the products tagged as having SELF character reveal the different ways in which attachments can act as barriers for divesting the products, either of a nostalgic character or because the products symbolize social relationships. While the main purpose of retaining products of nostalgic character seemed to be keeping memories from the past alive, we could see a desire to both stewards and bring into use the products symbolizing social relationships. However, bringing these products into reuse within the household or with a new generation was difficult as the products’ practical relevance had decreased over time. And the participants’ attachments would often make them averse to divestment paths that could otherwise lead to reuse.

ACT—Products Retained Due to Their Potential Usefulness

Another reason for retaining unused products was for their potential usefulness, 81 of the tagged products in the study had been retained for this reason (see Table 2). Products reported as useful were mainly from the category of furniture, furnishings, and loose carpets but also tools and household equipment. Another big category of potentially useful products was equipment for sporting, camping, and open-air recreation.

For some of the participants, the intrinsic quality of ‘being useful’ was enough reason to keep the product, even though they did not use the product. For example, participant 7 kept a small grill previously used when they lived in an apartment, but now replaced by two bigger, better grills, reasoning, “you can’t get rid of it, it’s an excellent grill, as you can see, it hasn’t been used for a while, but it’s an excellent grill”. Many tools were kept for the same reason, they were simply very good and useful tools, like Participant 20’s belt sander: “it came at a really good price, and I thought it was really great, but it is really great if you use it, and I haven’t used it”. These products were thus retained in the households for their potential usefulness and their envisioned excellent performance in scenarios that the owners believed would never happen, as exemplified by Participant 20 when asked when he thought the belt sander would be useful “well, yes, that’s if you’re going to renovate or fix something up, but I don’t know, maybe it’s got to… go.”

For other products, however, the potential usefulness was connected to a hope of being able to use the product in the future. As with the unused (and non-functional) record player kept in household P9, the husband tried to argue for retaining it because it would be useful if they ever wanted to play vinyl records again. However, in the interview, he also reflected on his own reasoning saying “that’s my justification, but I’m lying to myself” and “they just ended up staying, there’s not even a thought behind it, to be honest”. When questioned by his wife about who would want the record player, he concluded, “me, when I’m going to play records, but that won’t happen before I die”. In a similar vein, two other participants mentioned motorcycle gear that they kept with the hopes of using it again. One of them spoke about the difficulties in selling their motorcycle helmet, partly because used helmets can have hidden cracks and therefore be difficult to sell second hand. But also, because she felt mixed emotions getting rid of it. So, she retained the helmet to be used again, noting, “I hope more than I believe” (P2). The other participant with motorcycle gear had similar hopes for riding a motorcycle again but noted, “my wife keeps hers for nostalgia” (P7).

Another aspect related to potential usefulness is the sense of security provided by having products at hand. Tools were frequently mentioned in relation to this; having a wide range of tools meant that households could meet any needs that arose, especially those related to maintenance or fixing things in the home. Several participants mentioned the joy they felt by having the resources they needed, but also the joy in being able to share their tools with friends and neighbors, in a sense being resources themselves:

It’s such a joy when someone asks ‘do you have one of those?’ and you can lend one, or when the neighbour is swearing because they can’t get something loose and you can fetch the right tool and lend it. (P7)

Having products also afforded adaptability to the households. For example, their large collection of flowerpots allowed household P19 to replant any of their large number of indoor plants when the need arose. They considered selling the pots they did not use, saying:

but I mean, a pot, it’s not really that much money, I don’t know, but it just feels unnecessary to get rid of it because then maybe I’ll need to get new ones in the future or the leap becomes bigger to... get something done.

The reason for retaining flowerpots was thus connected to avoiding future work of acquiring pots and maintaining the household’s adaptability for future planting needs. Other households mentioned adaptability for a wider range of products, seeing potential usefulness is everything from half a roll of wallpaper to leftover tiles:

There’s something about utilizing the resources we have here. Because it’s so far to go, we can’t just go every time we need something. So, it’s about making do with what’s here, and since there’s so much, we usually manage to solve it. (P16).

Many participants expressed difficulties in evaluating the actual usefulness of the product, as it required speculating about what they would do in the future: “It COULD be good IF I do this thing. But if I don’t do this thing, then maybe it’s not useful” (P15) or guessing when the product would be used again: “it’s so classic, ‘could be useful some time’… maybe you need that screw 15 years later” (P13). The potentially useful products may be idle for long periods of times before being used again but many spoke of the positive experience of using a product again after a long time. For some, it reaffirmed that they had made the right choice in keeping it, for others it was the financial benefit of not having to replace the product, while others wanted to avoid the regret of having divested something that would become useful in the future.

In summary, the decisions to retain many of the products of an ACT-character seems to be related to uncertainty about future needs and activities, and the desire to be ready for whatever happens. These products appear to exist on a scale from products that contribute to household resilience and maybe will be used, to potentially useful products where participants hold on to them in hopes of once again using them (against better knowledge), to the intrinsically useful products which participants seem to appreciate more as product exemplars, rather than something that they will realistically need to use in the future.

Unwanted, Yet Still Retained Products

The largest category of tagged products in the study was Unwanted products (see Table 2), comprising a variety of products that were retained even though the participants wanted to get rid of them. Products tagged as Unwanted were mostly from the categories clothing, furniture and furnishings, and recreational items. As participants had no real desire to retain these products for sentimental or pragmatic reasons, the analysis instead revealed challenges and barriers related to the process of divestment, particularly the disposition process.

Barriers of Disposition

For some of the unwanted products disposition simply had not happened, and the reasons why highlight several disposition barriers. For some larger products, often furniture, the logistics of divestment was the greatest barrier. One interviewee had plenty of unused furniture stored in her basement, saying that “it would be a relief if someone else came and said they could take them, then I would give them away, so I don’t have to drag and carry them” (P11). Another interviewee found that no charities would come and pick up larger items, stating that “it is a shame, because otherwise the storage would be empty” (P4).

Another major disposition barrier was found to be a perceived lack of time to carry out the work associated with disposition, and that this work often has a lower priority compared to other household tasks. When asked why they had not sorted through their storage one participant said that they had “...not come that far. Time is not enough. I work full time, so there is not much time left to deal with it” (P17). Priorities also mattered, as one participant explained “when it is nice outside, we would rather go to the forest and pick mushrooms or meet [family friends] that we haven’t met in a while” (P19). Many participants also reported barriers associated with getting the work done to dispose of their unwanted products—“it is hard to go from thought to action” (P9). Participants tended to delay the work instead of doing it: “I wonder if I just reflect on it instead of just deciding a day [to dispose of the stuff]” (P11). P15 discussed the work of disposing of old, unused laptops and said, “mine has things saved that I need to open and go through, but for [my partner] I just don’t think it has happened,” indicating a view of the disposition process as something that happens to you rather than intentional actions you take.

For some households, the disposition process is already halted before reaching a disposal decision. One participant compares purchase with disposition, saying, “...I need to decide there and then if I want it or not, but now that I have it and intend to get rid of it, I can postpone the decision to another day” (P11). Avoiding the decision was a common theme; another participant kept things as “it is more about not having to make the decision to get rid of [the products]” (P10). Yet another participant spoke about the need to reflect deeper to get past the initial decision to keep:

If I start with the winter jacket down there, and ask myself why I save it, first I would say it’s useful. For what? I’m out in the forest in the winter. Is it really that? No, because when I’m there, I use other clothes, I don’t choose it and don’t think it’s a good jacket […] so, I think you stop asking why too early, because you have the space, and I don’t have the need nor time to sell it. Then it just stays there. (P19)

Selling unused products was particularly associated with being a lot of work for the interviewees. P14 exemplifies this with her ball gowns:

I thought I would sell them now when there are student balls, but then I realised I need to take a picture with the dress on and then my partner has to be home to help me, because I won’t manage on my own. That is why they haven’t been sold yet.

Other participants shared their perceptions of the effort of selling unused products, saying “it feels like a lot of work to be in contact with people and you hear about people calling all the time with crappy offers, I can’t deal with that” (P19) and “when you are buying or selling something you have to be on the edge of your seat all the time, I don’t like being constantly available” (P15). Because “it takes some effort to put up an ad and [be in contact with buyers] … so the things you sell have to be worth selling” (P16), selling was seen as an option only if it paid off, but it was difficult to value what was worth it. Others had opted to avoid some of the work and uncertainties by using a trader or an auction house, with P4 explaining:

I think they’re good at valuing products, and they reach a lot of customers. They do it right and pay you, so you won’t be tricked, a lot of people seem to be tricked when selling things [by themselves].

In summary, there appear to be many barriers associated with the work of disposing of products, from more concrete work of logistics and coordinating with buyers, to the more mental work of taking the time and making the decisions. However, among the Unwanted products there also appears to be products whose retention is driven by other factors, beyond disposition, which are explained below.

Barriers beyond Disposition

A bit counterintuitively, Unwanted products were retained in several households due to the owners’ wishes for the product to be used again by a new household. What hindered these products from being reused was that the owners could not see clear paths to circulate the products. One participant mentions his bookshelf that “we don’t intend to use, but it’s difficult because it is from the 1980’s. It is not very nice looking but is very high quality. So, no one wants it, but it feels really stupid to throw it away” (P7). While discussing that the only rational solution to their house full of unused things would be to throw everything in a skip, household P9 concludes “but it is such a shame that it is not reused”. Most participants stressed that they wanted their unused and unwanted products to be put to use again, but since they did not know how to make that happen, they retained the products in the hope that a path to a new owner would open up eventually.

Another factor complicating divestment was the perceived financial value of the product, which placed demands on finding a suitable way in which the product could be divested, like the porcelain of P2 “that will be sold at a flea market. It is too nice to throw away and too nice to donate.” However, divestment ways deemed suitable often demanded more work, hindering the divestment process:

I don’t like the hassle of selling things, I would rather give it away. But sometimes I notice that I question whether I should give a thing like this away because it’s still worth something. So, I end up doing nothing. (P19)

Additionally, households did not want to lose out financially, as with the children’s Halloween costume in household P3 that “cost so much and therefore I want to get the most out of it … If I got rid of it, I would be relieved because now when it is just laying around it could easily break”. This internal conflict between wanting to get rid of a product but not wanting to make a loss sometimes also took the form of a conflict between partners in a household, where for example the partner of P13, saying, “would like to be in charge of [selling], while for me it matters less if we make 500 or 1500 kronor for the stroller, because the money creates value regardless and we get more space.”

Some participants instead hesitated to divest their unwanted products as they expected to regret their decision, as one participant says:

For me, it’s probably an energy drain to get rid of things, even though deep down, I’d feel good about getting rid of them […] sometimes I can wonder, would I miss this... Because usually, you don’t. […] The tricky thing is that often you miss it right after you’ve thrown it away because that’s exactly when you need it. (P8).

The prospect of needing something just as you had gotten rid of it was frequently mentioned, either as a memorable experience or as a fear for the future.

A frequently mentioned phenomenon in relation to unwanted products was finding the right person to take over ownership of the product. What was meant by ‘right’ varied; for some it simply meant someone willing to pay for the product, as some participants were uncertain there was anyone out there interested in the product. Participant 14 reasoned around finding a new user for several unwanted products, saying:

The cake stand is not so difficult, if I post it online, but the [foreign language] books would require a lot of effort to find someone who could and would take care of them. I think the same goes for the vacuum cleaner, there’s probably someone who would be willing to take it, but then the question is who that person is and how do I find them. (P14).

Finding the right person could also soften a financial loss, as one participant reflected:

Not everything can be sold, and there are certain things I have that have been expensive which I can’t sell because I know I can’t get the value out of them. So, I keep them until I find the right person to have the item. And preferably, I want a personal relationship with that person. […] it’s typically those kinds of things that end up in limbo. (P2)

The right person could just as well be someone who would understand and use the product as intended. This was the case for the bobbin lace cushion P4 had inherited from her mother; “and I would like, even if I can’t sell it, for it to go to the right hands, to someone who enjoys lace-making.” The idea of the right recipient is reflected in another participant who reasons that she “...would rather give something expensive to someone who is dirt poor, than sell it cheap to someone who has money” (P2) as she wishes for her products to be used by someone who needs it and not sold cheaply to someone who would resell it at a higher price.

Finding the right person could ease divestment of unwanted products, as one participant explains about a mispurchase she wanted to divest:

Had I known that they would come to a place where they were used, it would be easier to get rid of them, now I am thinking that I am the only one who knows what it is and how to use it but that is not the case! (P6)

Finding a person to take care of the unwanted products appears to facilitate preconditions to divest products as it provides a clear path to reuse. It also appears to alleviate negative feelings associated with divestment, as the products come to what the current owner perceives as a good home.

In summary, while a product may be Unwanted by the household, we find that the owner’s wishes to do right by the product complicate divestment. For some participants, it was important to divest the product in a way that ensures reuse so as not to waste the potential usefulness or quality of the product. For others, it was important to find the right person to take over the product to ensure that the product would be treated right in its new home. While the participants have distinct and varied ideas about what would be the right way to divest their Unwanted products, there are challenges in executing these strategies effectively.

Discussion

This paper sets out to explore which unused products are retained in households and the reasons behind their retention in order to inform designers who are hoping to support the divestment of such products. We begin this discussion by exploring the underlying causes of product retention, followed by a section on how design can address these factors and support the divestment of unused products, enabling their further utilization.

In our study, we found unused yet retained products that could be categorized as having SELF, ACT, and Unwanted characters in reference to Hassenzahl’s apparent product character (Hassenzahl, 2003). Each of the categories can be associated with more specific reasons for their retention, but there are also underlying explanations that go across the product characters. Comparing the unused products of SELF and ACT character with products of Unwanted character, we find that SELF and ACT products are often retained for the potential value they could bring to the household, a perceived product benefit, while Unwanted products lack such value. The perceived product benefit can be many things, which is exemplified by the division into SELF and ACT character. For products of ACT character, the perceived product benefits relate the owner’s perception of a product’s potential usefulness. This usefulness can lie in the product itself but also in the products potential ability to be useful in a future scenario or for the household’s resilience to meet unexpected needs. But the perceived product benefits could just as well be the emotional or social value gained from nostalgic products and products symbolizing social relationships, which was frequently mentioned for the products of the SELF character.

The finding that perceived product benefits influence product retention aligns with prior research on perceived value, which suggests that value assessments—whether practical or sentimental—play a key role in disposition decisions (Haws & Reczek, 2022). Additionally, emotional, social, conditional, functional, or epistemic value derived from a product impacts decisions regarding its replacement (van den Berge et al., 2021). These values can be categorized as either pragmatic or hedonic, reflecting the study’s division into SELF and ACT product character. However, we can see that the benefits our participants see in their unused products often are connected to future scenarios where they think, or hope, that the products could be of value. In some cases, the interviewees were even aware that their assessment of the future usefulness of their products was wrong, as with the record player in household 9 or the inherited products in households P8 and P10. Thus, while households may perceive plenty of potential benefits in their unused products, the challenge lies in correctly assessing the products’ ability to satisfy the future needs of the households. When such assessments are incorrect, they may, in turn, act as unnecessary barriers to divestment.

For the products of Unwanted character, with no perceived benefits, the study instead reveals a divestment barrier associated with the work the participants foresaw in relation to the many steps of the divestment process, i.e. their perception of divestment work. This factor is related to the concept of consumption work, which is a term that denotes the consumer’s work with a product throughout its lifetime, from purchase and use to re-use and disposal, and is argued to be an important aspect to consider in order to understand participation in the circular economy (Hobson et al., 2021). With divestment work, we build on this concept to highlight the often substantial work associated with the divestment phase of consumption. Here, we also emphasize the perception of the work rather than the work itself, as the participants’ perceptions of divestment work clearly prevented unused products from being divested. The way they describe this work reveals that there are many activities and decisions to make during divestment, in line with divestment process descriptions of previous research (Dommer & Winterich, 2021; Poppelaars et al., 2020). To avoid this time-consuming and effortful work, our participants often opted to retain their products, thereby evading any challenging decisions and work associated with divestment. It is clear that it is not only the physical work that is a barrier for disposition but also the mental work of letting go. This aligns with the division of divestment into the sub-processes of disposition and detachment, as mentioned in the introduction (Poppelaars et al., 2020), both of which need to be supported in order to support the divestment of unused products. While perceived divestment work is especially prominent in the category of Unwanted products, we believe that this factor impacts all categories identified in the study to some degree, as the disposition of the product is the final hurdle to getting past the divestment process.

The products of Unwanted character also unveil an additional layer of complexity to the divestment process. Although these products were indeed unwanted, their owners hesitated to part with them until specific conditions were met. For some participants, it was crucial to divest the product in a way that ensured reuse, avoiding any waste of the product’s potential usefulness; this also applied to some of the ACT products. Others prioritized finding the right person who would appreciate and treat the product well. While this was most pronounced among unwanted products, it was also evident in relation to SELF products. As an example, an inherited product symbolizing a social connection with a past relative would likely be easier to divest if taken over by another relative who would appreciate the product and honor the memory of the past relative. Throughout our study, we observed that participants’ reasoning about what to do with their products was heavily influenced by what we conceptualize as the divestment conscience, i.e., an aspiration to do what is right and avoiding a feeling of having let down the product itself, other people, or the environment. In our study, we can see that this clearly complicates the divestment of products and may lead to unnecessary product retention.

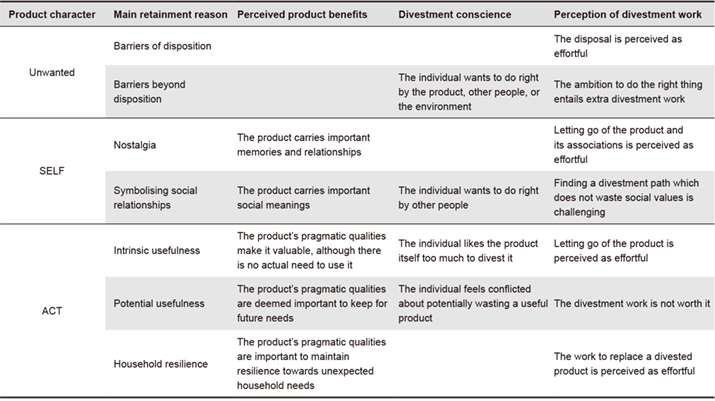

Together, perceived product benefits, perception of divestment work, and divestment conscience provide an explanation for why unused products of different characters are retained, as presented in Table 3. Depending on which products one aims to support the divestment of these influencing factors provide guidance to which barriers to address.

Table 3. Influencing factors causing retention of SELF, ACT, and Unwanted product categories.

In relation to past research on product retention, as presented in the outset of this paper, the factors of perceived product benefits and divestment conscience are more nuanced refinements of existing concepts rather than entirely new ideas. The pragmatic and hedonic dimensions of perceived product benefits align closely with previous research on product attachment. Similarly, the notion that divestment options perceived as easier on one’s conscience are more appealing has been indicated in studies such as those by Simpson et al. (2019) and Sarigöllü et al. (2021). The primary contribution of this study, however, lies in defining a new factor: the perception of divestment work, exploring its intricate relationship with the other two factors, particularly how divestment conscience influences it.

We propose that while perceived product benefits and divestment conscience strongly influence individuals’ intentions and feelings of ‘what they should do’ with their unused products, the actual behavior is heavily influenced by the perceived effort required to divest. The perception of the amount of divestment work necessary is shaped by the other two factors. For instance, the greater the perceived qualities of a product or the more significant the burden on one’s conscience, the more selective participants become in seeking an acceptable divestment option. This selectiveness, in turn, typically demands more divestment effort. Thus, his study confirms that products are sometimes retained not due to attachment, but because of the challenges involved in divesting them and that these challenges can become even greater when a product is considered ‘special’ in some way (Haws & Reczek, 2022; Türe, 2014). By conceptualizing these challenges as “divestment work,” we aim to highlight just how influential this factor appears to be, as evidenced by the findings of this study.

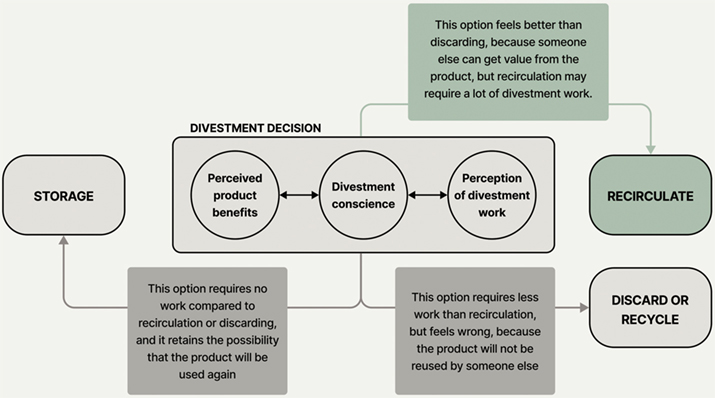

Overall, a recurring pattern emerged in how the participants rationalized their choices regarding unused products, such as keeping them in storage, recirculating them, or discarding them. As illustrated in Figure 3, products in this study were often retained because participants perceived the effort required to recirculate them as too high. At the same time, the participants tend to hold onto the hope that the products may be used again in the future rather than discarding them, which not only avoids the emotional weight of wasting potentially useful items but also eliminates the need for any practical divestment work altogether.

Figure 3. The influencing factors impact on the divestment paths of retaining (storage), discarding, and recirculating a product.

Design Opportunities

Design can play a crucial role in tackling the challenge of too many unused products accumulating in people’s storage. Building upon the factors affecting product retention presented in Table 3, various design opportunities can be uncovered.

Regarding the influencing factor of perceived product benefits, the most straightforward design opportunity is to create products that offer substantial benefits, encouraging their continued use even after a significant period in the household. This approach is particularly sensible for pragmatic benefits, which are heavily influenced by product features such as technical performance and quality. Design support for such issues is plentifully available under flags such as design for product-life extension (Bocken et al., 2016), design for durability (Bakker et al., 2014), and design for longevity (Carlsson et al., 2021). These cover several design strategies connected to extending the lifetime of products, such as design for repair (e.g., Roskladka et al., 2023) and design for upgradability (e.g., Khan et al., 2018). However, many of the products in this study were not unused due to their inadequate functionality, but rather since the households no longer had use for them. Thus, unused quality products were frequently held onto since they were too good to let go of, leading to a situation of passive use and redundant consumption, as described in the introduction. Therefore, while it is important to design products to promote active use over time, it is also important for designers to support detachment once the product moves out of active use, and to design for the day when the product is no longer needed (Clawson et al., 2015). In addition, one should also be careful not to design products that create a too strong perception of irreplaceability and uniqueness, as this may result in strong attachments that remain beyond active use (Kowalski & Yoon, 2022). However, what would likely help the households in this study the most would be to help them realistically assess the future needs of the household in relation to their product stock.

Reflecting on this study’s results, designing for detachment seems to not only be an issue of removing attachments caused by perceived product benefits, but also something that is closely connected to the divestment conscience. A gift, for example, could be kept not because of its hedonic value but because you do not want to feel like you are letting down the person who gifted it. Thus, from a design perspective, it would, in some cases, be reasonable to design for attachment, but in other cases, it would be more sensible to design for detachment by alleviating a bad divestment conscience hindering product circulation. However, advice on how to address this factor through design appears scarce. A notable example is the work of Poppelaars et al. (2020), who propose the guideline of “holding the user’s hand to say goodbye”. They argue that special care can be taken to help users distance themselves mentally and emotionally from their products. Specific procedures, such as trial divestment or allowing users to retain memories associated with the products, can thus contribute to a better divestment experience. In addition, divestment rituals (Mccracken, 1986) employed by consumers can also help them to erase the meanings invested in their products, to reduce the strange feeling that may occur when another user forms a relationship with the product.

The third influencing factor identified in the study is the perception of divestment work. The household visits underscore how significantly this perception impacts product retention. Reducing both the actual and perceived burden of divestment is critical, as it influences all divestment scenarios. Addressing this issue can be approached at various design levels. On a societal level, factors such as proximity to recycling centers or the ease of sending products by mail to other households play a major role in how much divestment effort is required. On a smaller scale, divestment work is often alleviated through service development. Numerous services facilitate product circulation, from large platforms like eBay to more niche, app-based services that help people rent products from one another or connect sellers and buyers with transportation solutions for second-hand goods. On a product design level, there is not so much design guidance available that specifically addresses divestment work. An exception is the Design for Recycling area (cf. Martínez Leal et al., 2020) which advocates that products should be easy to disassemble and materials should be easy to separate. However, design guidance specifically aimed at reducing divestment work and thereby enabling product circulation is not easy to find. One exception is the Design Toolkit by Rexfelt & Selvefors (2021), which includes multiple design guidelines on both a product and service level that aim to ease the exchange of products between people.

In addition to the design opportunities associated with each of the three identified factors, the household visits in this study also reveal additional opportunities. Many participants describe a barrier to engaging with their unused products at all. Moreover, they find it challenging to make informed decisions about whether to keep a product or not, and, if they choose to get rid of it, how to do so. This presents a significant opportunity for designers to assist consumers, as evidenced by the popularity of self-help literature and TV shows, such as the approach advocated by the decluttering guru Marie Kondō (2014). Moreover, it was apparent that many participants appreciated being part of this research study, as it prompted them to engage with their unused products.

Future Research

Further research on product retention and divestment is essential to better understand how to facilitate the circulation of unused products at their highest value and enhance product utilization. Clearly, there is much less understanding of the end of the consumption cycle compared to the knowledge we have regarding how and why people acquire products. Based on this study, we identify three specific areas that deserve future investigation.

The first area is to explore the household perspective in greater depth to enhance our understanding of product retention and divestment. In the interviews conducted for this study, reasons for retention that extend beyond the product-person relationship were frequently mentioned. Participants discussed various issues, including different responsibilities within their households, the importance of storage space in relation to divestment needs, and the overall low priority given to divestment activities compared to other household tasks. A more nuanced understanding could be achieved by viewing retention and divestment as integral aspects of everyday household life.

Secondly, this study focuses on the products that are retained in storage rather than on the ones that have been divested. Examining the products that are successfully recirculated would complement this research by enhancing our understanding of which items are being recirculated and the factors that positively influence and drive product divestment within the circular economy. While some research exists on this topic, it would be particularly interesting to explore different divestment conduits and compare them using the same or similar influential factors identified in this study. For example, the concept of divestment work could be a valuable factor for comparison, helping to clarify the specific actions associated with each conduit.

The third and final area for future research is to conduct more design-focused studies aiming to enable the divestment of unused products. The three key explanatory factors presented in this paper not only aim to provide a way to understand retention but also to offer a manageable and useful structure for characterizing retention reasons that can be applied in design. In particular, it would be beneficial to explore the factors of divestment conscience and perception of divestment work, which have received limited attention in design research. Additionally, studies that apply design principles to help individuals interact with their unused products and make informed decisions about them would be a valuable pursuit.

Reflections on Method

The 241 unused products included in this study were personally selected by the participants themselves. Consequently, these products do not offer a comprehensive representation of all unused items within households; it is not an exhaustive inventory detailing the various sizes of different product categories. Additionally, participants may have chosen certain items because they found them interesting or enjoyable to discuss. As a result, there might be an underrepresentation of ‘less significant’ objects, although it is worth noting that some mundane items (such as skirting boards and other miscellaneous objects) were indeed part of the selection. Despite these considerations, we do not consider this issue to significantly impact the study’s outcomes. The variety and quantity of the chosen products still provided ample examples for understanding and mapping the crucial factors in the households’ narratives.

Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that the discussion on design opportunities is not intended to be an exhaustive review. Rather, the goal is to showcase existing approaches related to the identified factors influencing product retention and to consider additional opportunities.

Conclusions

Explanations for why a product is retained in a household can be attributed to three key factors:

- Perceived Product Benefits: These encompass both pragmatic and hedonic advantages offered by the product. Whether it serves a practical purpose or brings emotional satisfaction, perceived benefits influence retention.

- Perception of Divestment Work: The effort required to divest a product plays a significant role. If the process of getting rid of an item—whether through selling, donating, or recycling—demands substantial time and effort, people may choose to keep it despite its lack of use.

- Divestment Conscience: People sometimes feel compelled to do the right thing by keeping products because they want to avoid feeling that they have let down the product itself, other people, or the environment.

Numerous unused products are retained in people’s storage because their owners hold onto the hope that they will eventually be used again. However, other products are kept even when such hope is slim or nonexistent, as the process of divesting them in a satisfactory manner would demand too much effort.

From a design perspective, significant attention has been given on enhancing emotional and pragmatic product benefits to increase product longevity. However, such efforts may also prevent recirculation of unused products, if it makes consumers hold on to them although they do not need them. The other two factors—perception of divestment work and divestment conscience—remain less explored. Additionally, many participants in the study encountered a significant barrier when it came to interacting with their unused products. They grappled with the challenge of making informed decisions regarding whether to retain a product or not, as well as how to divest it. This situation presents a valuable opportunity for designers to support consumers in assessing their future needs and aid them in their divestment-related decisions.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by funding provided by Formas —a Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development. Our sincere thanks go to all the participants in the study who generously invited us into their homes.

References

- Bakker, C., den Hollander, M., van Hinte, E., & Zijlstra, Y. (2014). Products that last: Product design for circular business models. BIS Publishers.

- Bocken, N. M. P., De Pauw, I., Bakker, C., & Van Der Grinten, B. (2016). Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, 33(5), 308-320. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681015.2016.1172124

- Carlsson, S., Mallalieu, A., Almefelt, L., & Malmqvist, J. (2021). Design for longevity - A framework to support the designing of a product’s optimal lifetime. In Proceedings of the Design Society (pp. 1003-1012). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/pds.2021.100

- Clawson, J., Pater, J. A., Miller, A. D., Mynatt, E. D., & Mamykina, L. (2015). No longer wearing: Investigating the abandonment of personal health-tracking technologies on craigslist. In Proceedings of the ACM international joint conference on pervasive and ubiquitous computing (pp. 647-658). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2750858.2807554

- Conde, Á., Birliga Sutherland, A., & Colloricchio. (2022). Circularity gap report Sweden - Re:source. https://resource-sip.se/en/circularity-gap-report-sweden-en/

- Cwerner, S. B., & Metcalfe, A. (2003). Storage and clutter: Discourses and practices of order in the domestic world. Journal of Design History, 16(3), 229-239. https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/16.3.229

- Dommer, S. L., & Winterich, K. P. (2021). Disposing of the self: The role of attachment in the disposition process. Current Opinion in Psychology, 39, 43-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.016

- Gregson, N., Metcalfe, A., & Crewe, L. (2007a). Identity, mobility, and the throwaway society. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 25(4), 682-700. https://doi.org/10.1068/d418t

- Gregson, N., Metcalfe, A., & Crewe, L. (2007b). Moving things along: The conduits and practices of divestment in consumption. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 32(2), 187-200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2007.00253.x

- Hassenzahl, M. (2003). The thing and I: Understanding the relationship between user and product. In M. A. Blythe, K. Overbeeke, A. F. Monk, & P. C. Wright (Eds.), Funology: From usability to enjoyment (pp. 31-42). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2967-5_4

- Haws, K. L., & Reczek, R. W. (2022). Optimizing the possession portfolio. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46. Article 101325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101325

- Hobson, K., Holmes, H., Welch, D., Wheeler, K., & Wieser, H. (2021). Consumption work in the circular economy: A research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production, 321, Article 128969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128969

- Jacoby, J., Berning, C. K., & Dietvorst, T. F. (1977). What about disposition? Journal of Marketing, 41(2), 22-28. https://doi.org/10.2307/1250630

- Khan, M. A., Mittal, S., West, S., & Wuest, T. (2018). Review on upgradability – A product lifetime extension strategy in the context of product service systems. Journal of Cleaner Production, 204, 1154-1168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.329

- Kowalski, M., & Yoon, J. (2022). I love it, I’ll never use it: Exploring factors of product attachment and their effects on sustainable product usage behaviors. International Journal of Design, 16(3), 37-57. https://doi.org/10.57698/V16I3.03

- Martínez Leal, J., Pompidou, S., Charbuillet, C., & Perry, N. (2020). Design for and from recycling: A circular ecodesign approach to improve the circular economy. Sustainability, 12(23), Article 9861. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239861

- Mccracken, G. (1986). Culture and consumption: A theoretical account of the structure and movement of the cultural meaning of consumer goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(1), 71-84. https://doi.org/10.1086/209048

- Myrorna. (2018). Så använder svenskarna [How Swedes use]. https://www.myrorna.se/artiklar/

- Nilsson, K., Strömberg, H., & Rexfelt, O. (2023, June 31). Nostalgia, gift, or nice to have—An analysis of unused products in Swedish households. In Proceedings of the 5th conference on product lifetimes and the environment (pp. 723-728). Aalto University publication.

- Poppelaars, F., Bakker, C., & van Engelen, J. (2020). Design for divestment in a circular economy: Stimulating voluntary return of smartphones through design. Sustainability, 12(4), Article 1488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041488

- Rexfelt, O., & Selvefors, A. (2021). The use2use design toolkit-tools for user-centred circular design. Sustainability, 13(10). Article 5397. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105397

- Roskladka, N., Bressanelli, G., Miragliotta, G., & Saccani, N. (2023). A review on design for repair practices and product information management. In E. Alfnes, A. Romsdal, J. O. Strandhagen, G. von Cieminski, & D. Romero (Eds.), Proceedings of the IFIP conference on advances in production management systems and production management systems for responsible manufacturing, service, and logistics futures (vol. 692, pp 319-334). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43688-8_23

- Türe, M. (2014). Value-in-disposition: Exploring how consumers derive value from disposition of possessions. Marketing Theory, 14(1), 53-72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593113506245