Touchpoint Design for Local Shops as a Community Hub

Eunji Woo and Ki-Young Nam *

Department of Industrial Design, KAIST, Daejeon, Republic of Korea

Local shops are private sector entities that also play a social role within the community. Despite their importance in providing the community with social values, there have been few attempts to understand their creativity and resourcefulness in creating community-anchored service experiences. In this context, we aim to discover the implicit strategies of local shop proprietors and convert them into actionable knowledge for creating social value through community-anchored service experiences. Empirical data were collected through interviews with 21 local shops, supplemented by on-site observations, and analyzed using both thematic analysis and cluster analysis. Consequently, a framework of service touchpoints categorized by Community Anchors and Customer Enticements was developed with six strategic positions for service touchpoint deployment, including: Local Treasure, Digging Ground, Influencer-in-the-Wild, Celebration of Imaginative Stories, Village Salon, and Pure Merchant. The article presents design implications for creating community-anchored service experiences in local shops by using key design materials: 1) resources, 2) place attachment, and 3) proprietor’s individuality.

Keywords – Community-Anchored Service Experience, Diffuse Design of Local Shops, Design Facilitation for Co-Design, Strategic Position for Service Touchpoint Deployment.

Relevance to Design Practice – This paper examined the tacit knowledge of local shop proprietors in designing community-anchored service experiences that foster the creation of social values within their neighborhood and enhance business competitiveness. The findings can aid design practitioners in facilitating local shop proprietors’ design activities to create effective service experiences.

Citation: Woo, E., & Nam, K.-Y. (2025). Touchpoint design for local shops as a community hub. International Journal of Design, 19(3), 63-82. https://doi.org/10.57698/v19i3.03

Received May 31, 2024; Accepted July 15, 2025; Published December 31, 2025.

Copyright: © 2025 Woo & Nam. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-access and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: knam@kaist.ac.kr

Eunji Woo is a postdoctoral researcher in Industrial Design at KAIST, where she earned her Ph.D. with a dissertation titled Designing Community-Anchored Customer Experiences for Local Shops. Her doctoral research examined the design process, technology mediation, design facilitation, and policy support, offering a holistic framework for strengthening the role of local shops in neighborhoods. Her broader interests include service design and community-level social innovation, with a particular focus on how everyday businesses can act as social infrastructure. She has designed and facilitated participatory workshops and co-design toolkits with local shop proprietors, social entrepreneurs, policy practitioners, and citizens. Through these efforts, she seeks to bridge academic research with practice and to position local shops as living laboratories for cultivating new forms of social capital and community building.

Ki-Young Nam is an associate professor of Industrial Design at KAIST. He is the founder and director of Designize, a DESIS Lab, where he conducts research for governments and industry, as well as supervises the research of Ph.D. and Master’s students. His research interests include defining and resolving complex problems in policy and social Innovation contexts based on design thinking. He publishes his research internationally in major design and design management journals and conferences. He advises governments and industry in various capacities. He has served as editor, executive, PC member, and reviewer for domestic and international academic organizations, including Vice President of the Korea Society of Design Science. He received a BA (Hons.) and MA degrees in Industrial Design from Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, University of the Arts London. Subsequently, he obtained a Ph.D. from Manchester Metropolitan University. Ki-Young held an academic position at the University of Lincoln in the UK before joining KAIST.

Introduction

Local shops are curious animals and are essentially private sector entities. However, at the same time, they play a social role for the community. Not only do they constitute a significant portion of national economies in many countries (Asian Development Bank, 2023; Main, 2024; OECD, 2023), but a source of significant social values, offering essential services intertwined with the well-being of the locals, serving as social hubs that bring communities together, and enhancing the vibrancy and diversity of urban life (Bookman, 2014; Ferreira et al., 2021; Gerosa, 2024; Hubbard, 2016; Hult & Scander, 2024; Yoon, 2024). In other words, local shops offer attractive lifestyles for the residents on the one hand, and shape urban experiences for visitors on the other, beyond their economic contributions.

For this study, we define local shops as small-scale, independently run businesses located within walkable urban neighborhoods (Lee & Cheng, 2023; Rao et al., 2024). These shops operate through physical, face-to-face service environments, fostering ongoing social interactions not only between proprietors and customers (Ferreira et al., 2021; Steigemann, 2017). Their autonomy, spatial intimacy, and proximity to daily life make them distinct from chain stores or online retail, positioning them as neighborhood anchors both economically and socially (Gerosa, 2024; Yoon, 2024).

The dual role of the local shop, which plays both commercial and social roles, makes designing innovative customer experiences for local shop services both vital and challenging. However, local shops have been largely overlooked in service design, since the scale of their operation is smaller and organizationally less complex, hence deemed manageable with what the proprietors could muster (Andres Coca-Stefaniak et al., 2010; Burgess, 2002; Nguyen et al., 2019). More significantly, they are not deemed to have the resources or capabilities for proper service design, even if they wanted it anyway. At the same time, the local retail industry is diverse and complex, comprising a wide range of businesses. In short, individual shops are too small for tailored service design, yet the industry as a whole is too complex for standardized service design.

Nevertheless, more than ever, local shops need service design due to a big shift in consumption behavior. The experience consumption and socially responsible consumption further drive the social value of the local shop, manifesting themselves in the global “shop-local” trend pivoting around the circular economy (Chaltas et al., 2021), driven by the Millennials and Gen-Z customers value-consumption behavior in many countries, including the UK, USA., Canada, Singapore, and South Korea (Bennett, 2022; Sanchez, 2021; Singapore Business Review, 2021; Shin, 2022; Streets, 2020). Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, people became reluctant to travel long distances for leisure activities, and as a result, their activities tended to pivot around the home, intensifying the shop local trend (Asian Development Bank, 2023; Faramarzi, 2021; Woo & Nam, 2021). The experience-centric and socially-aware shop-local trend has opened up new opportunities for local shops to offer more unique and meaningful experiences.

Now, local shops need to differentiate themselves from the mainstream shopping, anchored on a sense of community and social awareness (Florida, 2005; Gerosa, 2024; Peters & Bodkin, 2018; Woo & Nam, 2021). Therefore, the community values that local shops embody are a great asset and an effective differentiator for local shops, which is hard for profit-seeking big-name retailers to emulate. In turn, the customer experiences that entice people to the local shop need to be anchored in the community throughout the customer journey. However, creating such experiences has posed some significant challenges for local shops seeking to capitalize on the new opportunities presented by experience design. How can they engineer a departure from the simple provision of goods and services to design new community-anchored service experiences that achieve their social role for the community and cater to the new consumption trend without the help of service design?

Local shops have, up to now, relied on their proprietors’ creativity, intuition, and capabilities to capture trends and exploit them with the limited resources they could mobilize (Ferreira et al., 2021; Hult & Scander, 2024; Yoon, 2024). One could only marvel at what some of them could come up with in terms of creativity and resourcefulness from such scarcity. It is not difficult to find truly wonderful “diffuse designers” among local shop proprietors—non-experts who actively engage in the design process themselves—while professional designers act as facilitators supporting these activities (Manzini, 2015). These successful diffuse design works may not need to be replaced by expert design—i.e., design performed by those who have been trained as designers—altogether. However, they do need design facilitation to co-design their strategic positions for creating new community-anchored service experiences and further enhancing what they already have (Aguirre et al., 2017; Manzini, 2015; Mulder, 2018). Those less prepared to respond to the changing environment can be supported through design facilitation to engage with it effectively.

In this context, research is needed to identify how local shops actually create and deploy innovative experiences rooted in local and customer communities, in order to scale up and further intensify these individual efforts for better and more authentic local shop experiences that also hold social value for the community. Therefore, examining the following would be a valuable academic contribution: 1) service experiences for enticing customers through a local shop’s customer journey; 2) how such experiences are anchored in community; and 3) design implications for design facilitators who support proprietors in designing community-anchored service experiences.

This article begins with the Theoretical Background section, which contextualizes the research by providing the theoretical underpinnings of the key concepts. The section establishes the significance of community-anchored service experiences for local shops and discusses two Community Anchors identified from the literature, namely locality and interest. Following this, seven categories of Customer Enticements for the local shop are discussed, with the two sets of components serving as the main categories in constructing the conceptual framework of community-anchored service touchpoints. The Theoretical Background section is followed by the Research Methodology section, which presents the rationale for and detailed descriptions of the interviews and content analysis methods employed in the research. Finally, the Results and Findings and Discussions sections present: 1) a framework of service touchpoints by Community Anchors and Customer Enticements; 2) six strategic positions for service touchpoint deployment; and 3) three design implications for creating community-anchored service experiences in local shops by using key design materials—resources, place, and individuality.

Theoretical Background

Definition of Local Shops

Local shops have traditionally served as “third places” fostering community through everyday encounters (Oldenburg & Brissett, 1982). Recently, they have evolved into intentional community builders, creating experiences that strengthen ties among customers, neighboring businesses, and the broader community (Broadway et al., 2018; Ferreira et al., 2021; Hubbard, 2016; Hult & Scander, 2024; Ji, 2021; Maspul & Almalki, 2023; Yoon, 2024). For example, UK coffee shops now serve as active community spaces, hosting events such as reading groups and meetups, where proprietors and customers collaboratively foster a sense of belonging (Ferreira et al., 2021). Similarly, cafés in South Korea craft authentic atmospheres through design and naming that reflect communal values, inviting visitors to feel like they are entering a friend’s home rather than just a commercial space (Yoon, 2024). This shift, fostering everyday sociability, extends beyond cafés to include restaurants, boutique shops, bars, bookstores, art galleries, and hybrid venues offering a mix of retail and cultural functions (Ferreira et al., 2021; Hult & Scander, 2024; Yoon, 2024).

Witnessing this shift toward community-centered experience creation, we define a local shop as a small, privately owned, and autonomously run business outlet within an urban neighborhood. These shops place a strong emphasis on delivering unique and authentic customer experiences, varying across different social and cultural contexts. To align with our research purpose of examining how distinctive service experiences are created, we identified key characteristics of local shops from the literature to serve as selection criteria for interview participants.

Walkable Proximity

Local shops in our study are characterized by their hyper-local nature, typically situated within walking distances from homes or workplaces in urban environments. These shops are commonly found in the neighborhoods of Europe and Asia (Ferreira et al., 2021; Gerosa, 2024; Hult & Scander, 2024; Maspul & Almalki, 2023; Yoon, 2024), where the mix of residents and visitors creates a vibrant, dynamic atmosphere within a walkable area, akin to the 15-minute city concept (Moreno et al., 2021). The walkable proximity fosters frequent social interactions and a sense of ongoing community.

Small-Scale and Autonomy

A local shop is characterized by its small-scale operations, typically managed directly by its proprietor or their family members (Dessi et al., 2014; Yildiz et al., 2017). The independence and authenticity of its unique character are the greatest differentiators from larger, corporately managed chain stores and franchises, for which uniformity and standardized services are critical (Gerosa, 2024; Yoon, 2024).

Space-Centric Social Experience

A local shop in this study is characterized by a physical space where face-to-face interactions occur between shop proprietors and customers, not only for the provision of goods and services, but also for the development of deeper, non-transactional relationships. Moreover, social encounters among fellow customers and community members occur in a local shop, often serving as a social hub or a village well of a local community, fostering a distinctive social atmosphere (Ferreira et al., 2021; Smith & Sparks, 2000) in the space as a tangible manifestation of the shop’s unique character, where interactions among people are naturally cultivated. On a visceral level, the space itself acts as a critical touchpoint that differentiates a local shop with its unique and authentic identity (Yoon, 2024) from the standardized, uniform spatial experiences typically found in chain stores and franchises in regional areas.

Community Hub

A local shop in this study actively functions as a community hub by intentionally creating spaces and experiences that foster social connections (Ferreira et al., 2021; Gerosa, 2024; Ji, 2021; Yoon, 2024). This includes hosting community events, engaging customers in co-creation activities, designing spaces that encourage informal interactions, and utilizing promotional efforts to communicate social values and foster a sense of belonging. Such purposeful community anchoring strengthens ties not only between proprietors and customers but also among neighbors and local organizations, establishing the local shop as a vital social gathering place within the neighborhood.

Community Anchors and Community-Anchored Service Experience

The service experiences of successful local shops often foster a sense of belonging among those in the surrounding area, including proprietors, customers, and residents (Landry et al., 2005; Peters & Bodkin, 2018). In other words, a local shop service is anchored in the community.

The community-related nature of local shop services is supported by interdisciplinary research in Sociology, Customer Relations, and Marketing (Oldenburg & Brissett, 1982; Rosenbaum, 2006; Zukin, 2009; Goodwin & Gremler, 1996; Price & Arnould, 1999). Particularly in Marketing literature, the concept of community (brand and customer communities) has been explored as a strategic approach to relational marketing, shifting from transactional interactions to building deeper customer connections that enhance loyalty and competitive advantage (McAlexander et al., 2002; Peters & Bodkin, 2018). Distinguished from the notion of the local community, which loosely consists of residents, a customer community around a local shop referred to in this research is anchored on two elements: geographic locality and shared interests (Landry et al., 2005; McMillan, 1996; Muniz Jr & O’Guinn, 2001; Peters & Bodkin, 2018).

In an attempt to discover how communities can be built around a local shop, Woo and Nam (2021) have identified that the relationships between local shop proprietors and customers can be based on different communities: a locality-driven community (e.g., a local restaurant serving dishes made with local produce and telling interesting local stories about it); an interest-driven community (e.g., a bike café serving cycling-friendly foods and hosting bike community events); and a mixture of the two. In their subsequent study (Woo et al., 2023), the authors introduced the term “Community Anchors,” representing common values that can engage customers in experiences based on shared locality or interest. For this study, how local shop proprietors can use the two types of Community Anchors is presented:

- Anchoring on locality: Local shop proprietors can create service experiences by utilizing local resources, culture, and identity, as well as a co-located sense of belonging to the local community (Björk & Kauppinen-Räisänen, 2016; Gatrell et al., 2018; Schnell & Reese, 2003). It creates a unique and competitive experience that large franchises cannot easily replicate, while also instilling a sense of belonging among local customers.

- Anchoring on interest: Local shop proprietors can create service experiences that allow customers to enjoy their interests and socialize with others who share their interests (Ferreira et al., 2021; Rohman & Pang, 2015; Spekkink et al., 2022). Through such experiences, customers can meet others who share common interests, hobbies, and personalities, and they naturally feel a sense of belonging.

In this article, the unique experiences offered by local shops, anchored in the communities of the locality and their interests, are referred to as community-anchored service experiences.

Customer Enticements through Customer Journey

How, then, can a community-anchored service experience be created? Experience, in turn, can be designed through the careful management of tangible and intangible touchpoints in the service delivery process, because users perceive an experience by combining multiple encounters with all service touchpoints (Zomerdijk & Voss, 2010). To understand how local shop proprietors create community-anchored service experiences, it is crucial to examine how they utilize and design these touchpoints in their “diffuse” design practices. Because proprietors design activities occur through these touchpoints, their management is key to fostering meaningful community-based experiences.

Therefore, it is necessary to understand how community-anchored service experiences can be created by local shops from a holistic perspective. In this context, a customer journey can be an effective tool, as it visualizes a series of customer actions and interactions on a timeline encompassing the entire service experience (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Richardson, 2010). However, community-anchored service experiences at local shops may not be valuable per se. Not only do local shops need to play a social role and create social values through community-anchored service touchpoints, but they also create business values as a shop through the experiences designed to encourage patronage and loyalty from the customer.

The literature seems to agree on this point. Several studies on local shop service experiences have utilized a customer journey framework to encourage customer patronage, as seen in works by Nam et al. (2018), Rudkowski et al. (2020), and Woo and Nam (2020). Nam et al. (2018) investigated the effects of design values on customer loyalty, using the customer journey to identify specific touchpoints between the customer and proprietor. Rudkowski et al. (2020) demonstrated how unique customer experiences can be created across multiple touchpoints at each stage of the customer journey framework. More significantly for this research, Woo and Nam (2020) identified experiential factors on local shop patronage and proposed implications at each stage of the customer journey. The implications suggest ways to attract customers to local shops.

Thus, they are referred to as Customer Enticements and used to build a conceptual framework for community-anchored service experiences in this study (see Table 1).

Table 1. Types of customer enticements through the customer journey (Woo & Nam, 2020).

| Stage | Customer enticement | Definition |

| Before Arrival | Beyond the Shop * | Customers want to keep intimate relationships with local shops, both online and offline. |

| Waiting to be Entered/Seated | Appreciate Your Fans | Customers want to be appreciated for their efforts in patronage to be shown at the entrance. |

| Menu/Goods/Service Selection | Stir Up Imagination | Customers want to imagine diverse scenarios for future visits. |

| Staying | Go for an Authentic or Refined Interior | Customers want to feel a natural sense of authenticity from interiors and the right level of trendiness. |

| Balance Intimacy with Professionalism | Customers want local shop proprietors to be friendly yet professional. | |

| Be a Great Party Host | Customers want an atmosphere where they can enjoy socializing. | |

| Visit | Suggest Connected Activities | Customers want to discover connected activities near the shops. |

Note: * The label’s original name, Be a Friend, was slightly modified to better fit the concept of customer enticement.

We now have a framework with which to examine service experiences and their touchpoints. Naturally, these experiences need to be community-based, in line with the study’s aim. Therefore, the Community Anchors, as discussed in the previous subsection, are added to complete the categories of the conceptual framework of community-anchored service experiences. The framework is discussed in detail in the following subsection.

Conceptual Framework of Community-Anchored Service Touchpoints

Touchpoints occur whenever a customer interacts with a service across multiple channels and at various points in time (Bitner, 1992; Zomerdijk & Voss, 2010). Therefore, touchpoints can intensify engagement and emotional connections, serving as the primary components of experience design (Gupta & Vajic, 2000). In this research, the touchpoints that encourage customers to feel a sense of belonging to one another are defined as community-anchored service touchpoints, which can augment the social roles played by local shops within the community. Community-anchored service touchpoints can include physical environment, social actors, and social interactions with others (Gupta & Vajic, 2000). So, how do they manifest themselves in the shop to provoke a sense of belonging in the service experience?

While large retail organizations proactively design, organize, and deploy service touchpoints for intended experience (Bitner et al., 2008; Verhoef et al., 2009; Zeithaml et al., 2018), small local shops often lack the resources and expertise to do so, given that they are typically owned and managed by one person (Cadden, 2012; Megicks & Warnaby, 2008). Therefore, the proprietor is left to fend for themselves and make do with whatever touchpoints they happen to have for any community-related experience. In other words, the proprietor serves as both the service provider and the “silent” service designer (Gorb & Dumas, 1987) simultaneously. To better support their efforts through service design, it is necessary to understand how they utilize service touchpoints and enhance them through expert design facilitation. A systematic examination of the community-anchored service touchpoints currently in use can be effectively conducted with a conceptual framework that identifies how customers can be enticed into the shop in a way that fosters a sense of community.

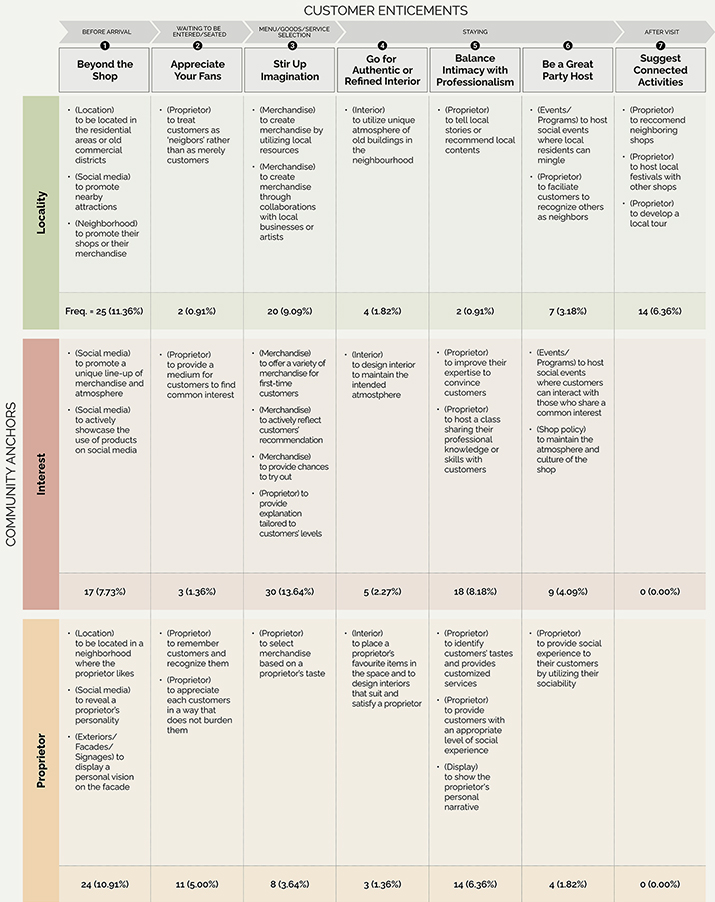

Therefore, we developed a conceptual framework that contained the two sets of categories from the literature: Customer Enticements and Community Anchors, in columns and rows, respectively, to identify the service touchpoints that fall under both categories (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of community-anchored service touchpoints.

Methodology

Case Selection

A combined approach of purposive sampling (Coyne, 1997) and convenience sampling (Stratton, 2021) was employed as a sampling strategy. That is because local shops providing unique, community-anchored customer experiences were needed to achieve the research aims; however, recruitment was challenging because such individual cases were not publicly known. For the sake of convenience, those available in the authors city were targeted and recruited based on the following criteria defined in the Definition of Local Shops subsection of the Theoretical Background section.

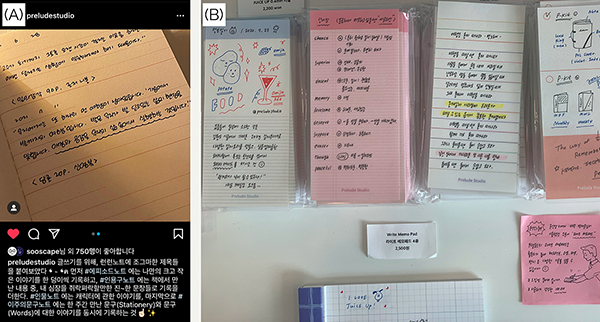

Consequently, 21 local shop cases in South Korea were selected, and 29 informants (16 female, 13 male) who were the proprietors of these businesses participated in semi-structured interviews (see Table 2). The informants were aged between 26 and 52 years old (average 36.2 ± 6.0 years), with experience running shops for one to ten years (average 3.8 ± 2.5 years). The business types of the participating shops were spread across various sectors, including apparel shops, photo studios, stationery stores, bakeries, restaurants, and bookstores. The number of employees, including proprietors and part-time workers, ranged from one to six.

Table 2. Informants demographics.

| ID | Business type | Age | Gender | Experience a | Num. of staff |

| P01 | Apparel & Living | 40 | F | 3 | 3 |

| P02-1 | Photo Studio | 40 | M | 10 | 2 |

| P02-2 b | Photo Studio | 39 | F | 10 | 2 |

| P03 | Stationer | 31 | F | 6 | 6 |

| P04 | Bakery | 34 | F | 2 | 2 |

| P05 | Restaurant | 35 | M | 5 | 1 |

| P06-1 | Bookstore | 36 | M | 9 | 1 |

| P06-2 | Bookstore | 36 | F | 9 | 1 |

| P07-1 | Café & Bookstore | 36 | F | 7 | 3 |

| P07-2 b | Café & Bookstore | 39 | M | 7 | 2 |

| P08 | Tea & Vegan Dessert | 32 | F | 1 | 1 |

| P09-1 | Bar | 34 | M | 4 | 2 |

| P09-2 b | Bar | 34 | F | 4 | 2 |

| P10 | Chinese Restaurant | 29 | F | 3 | 3 |

| P11-1 | Bakery | 35 | M | 3 | 2 |

| P11-2 b | Bakery | 26 | F | 3 | 2 |

| P12-1 | Roastery Café | 52 | M | 3 | 3 |

| P12-2 b | Roastery Café | 52 | F | 5 | 3 |

| P13 | Chocolatier | 35 | M | 1 | 6 |

| P14 | Botanical Bookshop | 33 | F | 1 | 1 |

| P15-1 | Dessert Café | 36 | F | 1 | 2 |

| P15-2 b | Dessert Café | 35 | M | 2 | 2 |

| P16 | Guesthouse | 36 | M | 2 | 3 |

| P17 | Photo Studio & Café | 34 | M | 2 | 2 |

| P18 | Ceramic Studio | 38 | F | 2 | 1 |

| P19 | Perfumery | 48 | M | 4 | 2 |

| P20-1 | Hardware Store | 35 | F | 5 | 3 |

| P20-2 b | Hardware Store | 29 | F | 5 | 1 |

| P21 | Liquor Shop | 31 | M | 2 | 1 |

Note: a The number of years the store has been in operation; b These cases involved two interviewees.

Data Collection

The semi-structured interview (Longhurst, 2003) was the primary data collection method. In order to ensure the reliability of the interview study (Kallio et al., 2016), the interview protocol was prepared in four steps:

- Construction of interview themes from literature: The interview protocol was guided by the framework of community-anchored service touchpoints, as introduced in Figure 1. This aimed to uncover proprietors’ tacit knowledge in creating community-anchored customer experiences.

- Formulation of a main set of interview questions common to all participating businesses: Based on the themes, the main set of interview questions was formulated to prompt local shop proprietors to share their intentions and experiences in building/maintaining relationships with their customers. Example questions are listed in Table 3.

- Formulation of contextualized follow-up questions: Follow-up questions specific to individual businesses were formulated based on unstructured on-site observations (Mulhall, 2003) and contextual inquiry (Wixon et al., 1990) conducted at each informant’s business. This approach aimed to collect richer and more contextual empirical data with each shop’s community-anchored customer experience and service provision reflected in the interview questions. First, we observed daily interactions between the proprietor and customers in offline spaces and on social media. Thereafter, we implemented action research to gain first-hand experiences by personally making purchases and participating in shop activities and programs. Additionally, we reviewed customers’ online reviews and any published interviews with the proprietor.

- Implementation of semi-structured interviews: One-to-one interviews were conducted between May and September 2021 at the informants’ business sites (i.e., local shops) to obtain contextual answers (see Figure 2). Each interview lasted approximately one hour. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis.

Table 3. Excerpt from interview questions.

| Customer enticement | Example questions |

| Beyond the Shop | What online touchpoints are being operated to interact with and establish relationships with customers? How are they being operated? |

| Stir Up Imagination | Do you make recommendations to customers when they are browsing menus/products? If yes, what is your know-how in offering recommendations? |

| Be a Great Party Host | Have you ever organized social gatherings for your customers? What are your tips for encouraging customers to become friends with each other? |

Figure 2. Interviews with local shop proprietors.

The transcribed interview data, field notes, and photos taken in the shops were documented. The data were managed by Atlas.ti 22, a qualitative data analysis software.

Data Analysis

The interview data included the proprietor’s “implicit strategies” (Nam, 2001) to deploy service touchpoints. They unconsciously and intuitively execute such strategies to build customer communities for their shops. In order to discover their implicit strategy, we used a mixed-method approach. First, the interview data were thematically analyzed to identify what kind of service touchpoints the proprietors used through deductive coding. Second, cluster analysis was conducted to ascertain how they deployed the touchpoints by clustering similar patterns of touchpoint deployment across the cases. This led to the discovery of strategic positions adopted by proprietors for service touchpoint deployment toward creating community-anchored service experiences.

The thematic analysis method categorizes the codes into meaningful themes and develops insights through qualitative interpretation (Bernard & Ryan, 1998). However, the data collected for this research made it difficult to grasp patterns at a glance due to the voluminous, complex, and multifaceted nature of the data collected. The added dimension of the conceptual framework that contained the codes made it even more complicated. As such, it was not possible to establish touchpoint deployment strategies from the thematic analysis alone. Therefore, we used cluster analysis to reveal the patterns among the datasets, each representing the coded service touchpoint matrix of a case, through relational proximity between different matrices (Guest & McLellan, 2003; Prevett et al., 2021). In other words, we examined the co-occurrence of the service touchpoint deployment practices across the cases, with each co-occurred cluster representing a local shop’s implicit strategic positions for community-anchored service touchpoint deployment.

To ensure trustworthiness in the thematic analysis (Nowell, Norris, White, & Moules, 2017), we invited four experts with over two years of design research experience to participate as coders. We developed a codebook containing the name and definition of each code to ensure consistent coding across multiple coders. After independent coding, the coders iteratively discussed code-quotation matches, labeling, and the structure of codes to reach a consensus.

The whole analysis process consisted of six steps. The first four steps were related to thematic analysis, while the last two steps were related to cluster analysis.

- Setting a priori coding scheme: The priori coding scheme constructed from literature was used for both 1) a formative framework for the interview protocol; and 2) an analytical framework for the interview data. The framework was a matrix with 1) the columns containing the seven Customer Enticements; and 2) the rows containing the two Community Anchors (see Figure 1).

- First coding by Customer Enticements (column): Four coders extracted and highlighted texts that fit the seven priori codes of Customer Enticements, according to the codebook. A total of 208 coded data were extracted. Then they examined the raw data to identify the types of touchpoints through which the Customer Enticements were deployed in each case, along with the deployment methods for the touchpoints and the proprietor’s intended experiences.

- Second coding by Community Anchors (row): The second coding was basically categorizing or tagging the coded data with the two Community Anchors contained in the row.

- Filling in the conceptual framework: The framework was filled in with the results from the thematic coding to become a service touchpoint framework.

- Preparing datasets for cluster analysis: the number of touchpoint entries in each cell within the service touchpoint framework was counted. A matrix of the number of entries in each cell per case was created for cluster analysis (a total of twenty-one matrices).

- Conducting cluster analysis for revealing cross-case patterns of service touchpoint deployment: matrices displaying similar patterns of the specific touchpoint counts contained in the cells across the cases (co-occurred touchpoints) were clustered using Quanteda (Benoit et al., 2018), an R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data.

Table 4. Some results of coding analysis.

| Coded data a | Customer enticement | Community anchor |

| (P16) "I believe it's important to have urban culture within a 15-minute walk for customers to enjoy. I also post social media content introducing neighboring shops, cafés or restaurants, as well as local events and news." | Beyond the Shop | Locality |

| (P03) "Certainly, you can choose the best pen after actually using it to write. That's why I encourage my customers to freely test all the stationery items freely in my shop. I arrange pens randomly and provide notepads with outlines drawn on them. This way, customers can comfortably try out the items." | Stir Up Imagination | Interest |

| (P05) "Choosing a bar seat means they want to engage in conversation with me. I usually share more small talk than evaluations for dishes. Regulars seem to value memories of enjoyable conversations with me over the taste of the food, which is why they become regulars." | Balance Intimacy with Professionalism | Proprietor |

Note: a All the interview transcripts were originally in Korean but have been translated into English.

Results and Findings

Framework of Community-anchored Service Touchpoints

As a result of the priori coding, the conceptual framework of community-anchored service touchpoints established in the literature review section has been re-constructed as the framework of strategic use of community-anchored service touchpoints, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Framework of community-anchored service touchpoints (click on the image to see a larger version).

The row of this framework is Community Anchor; unlike what was identified in the literature review section, a new type has been discovered as the result of the analysis, resulting in a total of three Community Anchors: Locality, Interest, and Proprietor. It implies that the service experience of a local shop can evoke a sense of community among people, not only through common locality or interest but also by anchoring to the shop proprietor. As local shops are independently operated businesses, anchoring to the individual proprietor is obvious and can be considered a distinguishing characteristic from typical franchise retail shops. The column of this framework represents Customer Enticement and is consistent with what was identified in the literature review.

The intersection of each row and column represents how local shop proprietors deploy specific touchpoints to act as a particular Customer Enticement on a Community Anchor. For example, touchpoints acting as the Be a Great Party Host enticement anchored on Locality include events, programs, and a proprietor. At the bottom of each cell, the frequency of the coded texts placed in the cell and their percentage in the 208 total coded texts are shown. The top three enticements anchored on Locality were Beyond the Shop (11.36%), Stir Up Imagination (9.09%), and Suggest Connected Activities (6.36%). The top three anchored on Interest were Beyond the Shop (7.73%), Stir Up Imagination (13.64%), and Balance Intimacy with Professionalism (8.18%). The top three anchored on Proprietor were Beyond the Shop (10.91%), Appreciate Your Fans (5.00%), and Balance Intimacy with Professionalism (6.36%). A local shop service experience is not solely crafted through a single interaction with a specific touchpoint at a particular stage; rather, it is holistically created through multiple touchpoints throughout the service journey. Therefore, we identified patterns in touchpoint deployment strategies through cluster analysis, which are described in the following subsection.

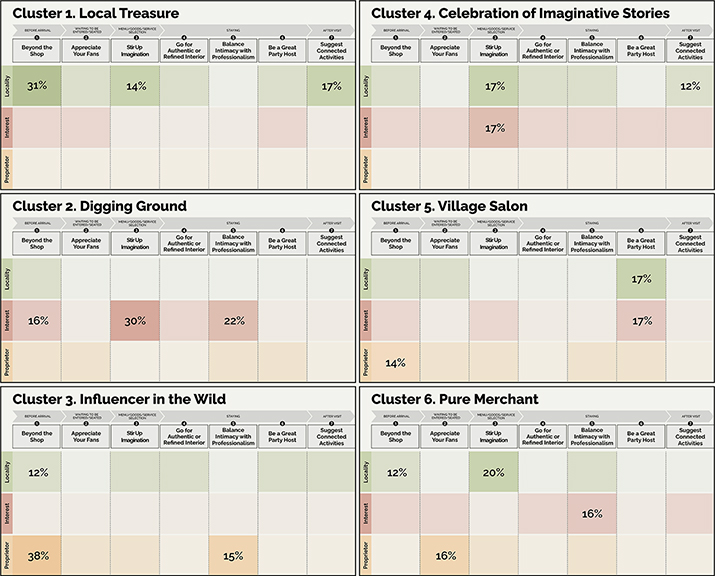

Strategic Positions for Service Touchpoint Deployment

Six strategic positions for service touchpoint deployment adopted by local shops were discovered from the cluster analysis: Local Treasure, Digging Ground, Influencer-in-the-Wild, Celebration of Imaginative Stories, Village Salon, and Pure Merchant. As shown in Figure 4, each strategic position was interpreted based on the most frequent Community Anchor and Customer Enticement codes. Numbers are indicated only in the top three cells, representing the highest frequencies of coded texts discovered from cases within each cluster.

Figure 4. Six strategic positions for service touchpoints deployment (click on the image to see a larger version).

Local Treasure

The Local Treasure position was discovered in the local shops in a neighborhood where outsiders were rarely seen. Such local shops played on local attractions to entice outsiders into the neighborhood—discovering, developing, promoting, and capitalizing on the places to visit, eat, and drink, or activities to enjoy. On the other hand, the local attractions, or treasures, served to build an emotional bond with the locals through the shared locality. As shown in Figure 4, this position was found to be mainly anchored on Locality, and highly related to Beyond the Shop, Suggest Connected Activities, and Stir Up Imagination enticements on the customer journey. In this strategic position, specific touchpoints, such as curated merchandise, social media posts, and even the neighborhood itself as an extended experiential setting, serve as key design elements through which proprietors, as diffuse designers, could transform locality elements into customer experiences.

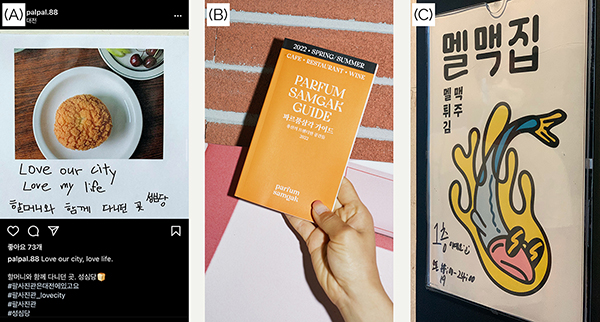

Most closely aligned with proprietors’ core business is the use of curated merchandise—touchpoints imbued with local stories—to implement the Stir Up Imagination enticement anchored on Locality. For example, the guesthouse (P16), located in the old district of Jeju Island in South Korea, serves as a popular spot for island tourists seeking an authentic experience of the local lifestyle. The proprietor featured handmade T-shirts co-created with a local artist, transforming everyday merchandise into a platform for playful storytelling. They also offered breakfast menus using granola from local produce, and bar snacks that evoked customers’ childhood memories of traditional Jeju dishes like fried mackerel [see Figure 5(C)]. P16 stated:

The fried mackerel is quite unique, so we get a lot of young tourists coming in, but it’s also a nostalgic dish for the local older folks. I’ve seen parents bring their kids here just to share that experience together. It’s amazing how this one menu item brings together outsiders and locals, young and old, all in one place.

These offerings served as edible and wearable touchpoints that linked customers to the sensory texture of Jeju life. Similarly, the perfumery (P19) developed a series of signature scents inspired by Itaewon and Hangang—neighboring features of Seoul—allowing visitors to take home a multisensory memory. Through these carefully designed touchpoints, local shops stimulated the imagination of customers and evoked emotional resonance tied to a place.

To implement the Suggest Connected Activities enticement (locality), proprietors created touchpoints that linked their shops to broader neighborhood experiences. For example, the perfumery (P19) developed curated local guidebooks for on-site distribution [see Figure 5(B)]. When asked why the perfumery (P19) was self-publishing local guidebooks, the proprietor answered:

Becoming a focal point for the community in this neighborhood also benefits my business. Customers visit my perfumery to experience the scents, and the guidebook helps them explore the neighborhood. When they return home and reminisce about this neighborhood, they’ll also recall those scents.

Among the enticements, the one most distinct from the shop’s core activities is the implementation of the Beyond the Shop enticement (locality), where proprietors leverage social media as a primary touchpoint to feature the attractiveness of the neighborhood. For example, the photo studio (P02) introduced local restaurants, along with their associated personal stories, through social media [see Figure 5(A)]. P02 stated:

When we talk to visitors from other areas, many haven’t been to Daejeon before. They often search for things to do after photo shoots, and I wanted to highlight the hidden gems of our city. Local restaurants are an easy and popular way to start. I really want them to experience Daejeon, not just come for photos.

Through these practices, local shops play a significant social role by creatively utilizing local resources, serving as a unique local identity, and fostering an authentic culture of the neighborhood.

Figure 5. Cases of Local Treasure: (A) The photo studio, P02, introduces local restaurants with the associated personal stories through social media; (B) The perfumery, P19, publishes a local guidebook every season; (C) The guesthouse, P16, offers a special bar menu through collaboration with local fishermen.

Digging Ground

The Digging Ground position provides customers with a playground on which they enjoy digging into a particular interest, e.g., stationery, vegan dessert, herbal tea, and chocolate, serving customers within and beyond the local area. Mainly anchoring on Interest, the Digging Ground position was found to be highly related to Stir Up Imagination, Balance Intimacy with Professionalism, and Beyond the Shop enticements on the customer journey, as shown in Figure 4. In this position, the customer’s interest is activated and sustained through specific touchpoints such as curated merchandise, interactive spatial arrangement, and the knowledgeable presence of the proprietor.

To implement the Stir Up Imagination enticement anchored on Interest, proprietors deployed carefully designed merchandise-based touchpoints to facilitate exploratory and sensory engagement. The stationer (P03), specialized in uniquely designed stationery, prioritizes creating an enjoyable offline experience for customers, featuring accessible merchandise arrangements and curated combinations like smooth pens with textured paper to enhance tactile experiences (see Figure 6). P03 mentioned, “Many customers return, eager to try out the newly released products. I also believe they develop a connection to the space because they leave their mark here during their experience.” Furthermore, the tea café (P08) and the chocolatier (P13) offered sampler kits such as tea or chocolate sets, enabling customers to explore a variety of tastes or scents before committing to a full purchase. These merchandise-based touchpoints allowed even first-time customers to engage with the shop’s thematic world in a playful and low-pressure manner, stimulating their imagination and deepening interest-based loyalty.

Figure 6. P03, a stationer, adopts the Digging Ground position:

(A) P03 actively showcases the use of stationery on social media; (B) P03 places the goods in disorder along with used items.

Moving from tangible, merchandise-based touchpoints to more interpersonal interactions, proprietors implement the Balance Intimacy with Professionalism enticement (interest). One key touchpoint was the tailored customer interaction at the point of service. Proprietors adjusted their tone, content, and depth of explanation based on the customer’s level of interest, often using informal cues or direct questioning to calibrate engagement. For instance, the tea café (P08) inquires about a customer’s previous meal or their current mood to recommend a tea that complements their experience, ensuring that even those unfamiliar with tea can enjoy it fully. Another type of touchpoint was learning-based programs, such as in-shop classes or tasting sessions. The chocolatier (P13) provided structured opportunities to explore the domain knowledge behind the bean-to-bar chocolate processes, helping to illuminate what many in the public may not yet understand.

The proprietors noted that these interpersonal interactions attracted repeat visitors, allowing them to gradually build confidence and appreciation for the products, which in turn deepened their overall interest. This anchoring on Interest extends beyond attracting new customers with intriguing content, fostering participatory and repeat engagement. Proprietors customized their service based on customer intent, treating visitors as cultural co-participants rather than one-time buyers.

Likewise, local shops embracing the Digging Ground serve as a physical hub for interest-anchored communities, drawing visitors from beyond the neighborhood who share these passions. The Digging Ground position plays a social role by fostering a sense of community among the “birds-of-a-feather” and enriching the cultural tapestry of the locality.

Influencer-in-the-Wild

The Influencer-in-the-Wild position refers to cases where the proprietor’s personal charm, taste, or lifestyle is transformed into experiential touchpoints that entice customers. Rather than relying solely on goods or services, these local shops leverage curated personal artifacts, informal communications, and expressive spaces to project the proprietor’s identity. Such expression is particularly effective in domains where customers seek affective resonance with the proprietors’ personal charisma and sensibility, such as independent bookshops with book diagnosis and LP bars with music selection. The analysis, as shown in Figure 4, found this strategic position to be mainly on the Proprietor community anchor, and highly related to the Beyond the Shop, and Balance Intimacy with Professionalism enticements on the customer journey.

Figure 7. Cases of Influencer-in-the-Wild': (A) The café, P17, showcases the proprietor's car in the shopfront to attract people with his travel stories. (B) The bookshop, P06, prints the proprietor's personal thoughts on books on the receipts.

To implement the Beyond the Shop enticement anchored on Proprietor, local shop proprietors strategically deployed touchpoints that extended their presence and values beyond direct transactions. For example, the proprietor of a brunch café (P17), a renowned traveler who gained widespread recognition through his world tour experiences, attracted numerous fans eager to learn more about his adventures. Against this backdrop, P17 strategically parked and displayed the car used during his global travels in front of the shop and shared its story through both the physical shopfront and Instagram. The car itself became a symbolic touchpoint that expressed his lifestyle, enticing visitors drawn by personal curiosity and admiration [see Figure 7(A)]. Another proprietor, the restaurant (P05), embedded their personal philosophy in the shop exterior or street-facing layouts to invite passers-by, and the book café (P07) crafted physical newsletters that were distributed on the street, offering glimpses into their thoughts and daily routines. Through such curated expressions, the shop environment reflected the proprietor’s identity in visible ways, helping customers understand their values and approach more clearly.

After being enticed by these personalized touchpoints, customers engage in intimate interactions with the proprietors and become actively involved in the community, forming deeper connections that go beyond mere transactional relationships. Proprietors employed personalized touchpoints that conveyed their character, expertise, and values to implement the Balance Intimacy with Professionalism enticement (Proprietor). The bookshop (P06) created “receipt diaries” that printed personal thoughts and insider commentary on book publishing, turning a mundane transactional medium into a storytelling channel [see Figure 7(B)]. Customers who were eager to immerse themselves in the proprietors’ personal tastes and lifestyles began to gather, creating bonds through unique shared experiences like morning rituals with the proprietor at the book café (P07), or small gatherings at favorite parks with the brunch café owner (P17), thereby deepening their connections and sense of community. These touchpoints allowed customers to form a personal connection with the proprietor, cultivating familiarity and emotional trust within the service space.

This study found that the Influencer-in-the-Wild position can foster emotionally resonant communities through the proprietor’s ongoing expression of self. In many cases, customers were initially drawn by the proprietor’s personal charm or worldview. However, as they repeatedly encountered the proprietor’s values and stories expressed through space, artifacts, and conversations, these interactions accumulated into a deeper relationship. Over time, customers developed emotional connections not just to the person, but to the broader culture and ethos that the shop embodied. In the cases of P05, P06, P07, and P17, these bonds evolved into informal communities of regulars who shared similar sensibilities, lifestyles, or cultural interests. Importantly, these communities were not limited by geography; rather, they formed around the proprietor as a community anchor, whose lived identity offered continuity, meaning, and a sense of belonging that extended beyond the local.

Celebration of Imaginative Stories

The Celebration of Imaginative Stories position provides customers with unique and attractive stories that the local shop proprietor aims to project to the customer. As depicted in Figure 4, this position is mainly anchored on the Locality and Interest community anchors, and is highly related to the Stir Up Imagination and Suggest Connected Activities enticements on the customer journey. This dual anchoring is most often realized through the use of the Stir Up Imagination enticement, wherein merchandise is curated in distinctive ways and enriched with stories, allowing touchpoints to convey both locality and interest.

Figure 8. Cases of Celebration of Imaginative Stories: (A) The botanical bookshop, P14, displays books showcasing the proprietor's expertise as a florist. (B) The zero-waste shop, P01, features eco-friendly products from neighboring shops.

For example, a traditional liquor shop in Daejeon, P21 displayed Korean traditional liquor with interesting behind-the-scenes stories regarding the creators who developed the products, the ways of making cocktails, and other customers’ recommended snacks that go well with each liquor. This enticement sparked curiosity and interest regarding Korean traditional liquor culture among customers and made them celebrate the culture. Meanwhile, the botanical bookshop (P14) tailored its book curation to the needs of local floral professionals. By anticipating their specific interests and pre-stocking hard-to-source foreign titles, the shop not only offered a locality-sensitive service but also supported the work patterns of a specialized community. In both cases, merchandise curation served as a key touchpoint that conveyed both a sense of place and thematic coherence.

Furthermore, to implement the Suggest Connected Activities enticement in this position, proprietors recommended nearby places that reflected the thematic identity of their shop. For example, the zero-waste shop (P01) recommended neighboring shops aligned with its eco-friendly values to provide connected activities to their customers pursuing a sustainable lifestyle [see Figure 8(B)]. In this case, the proprietor herself acted as a key touchpoint by verbally sharing personal favorites with customers during their visits. Alternative information mediums, such as printed materials or social media, can also serve to gather interest-anchored communities around the neighborhood.

Local shops adopting the Celebration of Imaginative Stories position engaged customers by curating narratives rooted in both Locality and Interest, transforming everyday touchpoints into platforms of storytelling. These narratives, shaped through the proprietor’s values, customer input, and neighboring collaborations, were not only expressions of identity but also invitations for collective meaning-making. Through this process, shops evolved into neighborhood story hubs, gathering diverse voices and fostering emotional connections.

Village Salon

The Village Salon position provides a community hub in the neighborhood where neighbors can meet and interact with one another. The analysis revealed that Village Salon anchors on all three community anchors (Locality, Interest, and Proprietor) evenly and on the Be a Great Party Host and Beyond the Shop enticements in particular (see Figure 4).

To implement the Be a Great Party Host enticement anchored on Locality and Interest, proprietors employed programmatic touchpoints such as regular social gatherings, community events, and conversational programs to foster social interaction. For example, the café (P07) organized a Friday night program called a “secret hideout”, where local residents could candidly share life concerns, fostering emotional connection and mutual support. The wine bar (P09) hosted diverse social events, including an introvert-friendly wine party, a feminist book club, and a wine learning session for the serious, each designed to attract different micro-communities with shared values. These gatherings were anchored on Locality in that they addressed shared experiences and everyday concerns of neighborhood residents, while also drawing on shared Interests such as literature, wine, or social issues to form meaningful sub-groups within the broader community.

The Village Salon position was found to increase customers satisfaction with the local shopping experience through rich interactions and relationships amongst customers. In the case of Village Salon, the key touchpoints are the events/programs organized by the proprietor. As the party host, the proprietor plans these programs with the types of people who will gather and interact in mind. Participants rely on the proprietor’s charm and values to decide whether to visit the shop and attend the party. This is why the Beyond the Shop enticement anchored on Proprietor showed the third highest frequency in this strategy.

Local shops adopting the Village Salon position serve as gathering places where locals engage in regular socializing and informal interactions. Unlike naturally occurring third places (Oldenburg & Brissett, 1982), these shops deliberately cultivate community bonding through programmatic touchpoints such as weekly events, themed discussions, and informal meetups designed by the proprietor. Through this intentional facilitation, the shop becomes a living community hub where a sense of belonging is actively built rather than passively formed.

Pure Merchant

The Pure Merchant position is the basic strategic position around the key business activity for attracting regular customers in local shops, primarily found in the food and beverage business, such as bakeries, cafés, and restaurants. This position does not focus on specific community anchors or enticements, but is evenly distributed: Stir Up Imagination anchored on Locality, Balance Intimacy with Professionalism anchored on Interest, and Appreciate Your Fans anchored on Proprietor, which were frequently found.

To implement the Stir Up Imagination enticement anchored on Locality, the restaurant (P10) adjusted its menu offerings based on neighborhood preferences, introducing seasonal dishes and flavor profiles that reflected local tastes. The menu itself served as a dynamic touchpoint that embodied community feedback and localized creativity. In the case of the bakery (P11), professional expertise was communicated through visual and textual touchpoints such as illustrated posters of the baking process, brochures on ingredient sourcing, and display signage introducing the day’s special. These elements demonstrated the baker’s craftsmanship and deepened customers’ appreciation of the products. For the dessert café (P15), the proprietor’s warm greeting, handwritten thank-you notes, and personalized drink recommendations served as interpersonal touchpoints, expressing a deep appreciation for regulars and reinforcing emotional loyalty.

This position is effective in creating a customer community centered around the local shop, based on the attitude and know-how of local merchants toward their key business activities. Without relying on overt performativity, Pure Merchant shops foster trust through consistent service and steady presence in everyday life. Over time, such reliability and familiarity often lead to friendships between proprietors and regular customers, further embedding the shop within the local social fabric.

Design Implications

The findings of this study can provide implications for designing service touchpoints to create community-anchored experiences. From a design perspective, the six strategic positions for service touchpoint deployment identified in this study reveal how key experiential elements—resources, place, and individuality—can be used as design materials. The design activities involving these materials do not necessarily require specialized design skills. Instead, they draw on the inherent creative abilities everyone possesses within the context of diffuse design (Manzini, 2015), based on the field-specific knowledge and experience that proprietors bring to the process. However, this does not mean that it is good to leave the proprietors to their own devices in handling the materials to design community-anchored experiences. They still require expert facilitation for the design activities, as designers in other contexts typically do. These point to new opportunities for design facilitation that support proprietors—non-design experts—in transforming their assets into meaningful service experiences. The subsections below discuss how specific experiential elements can be used as design materials, as well as implications for design facilitation.

Resource-related Experience

Traditionally, local shops have utilized local resources for production and distribution (Ronnahong-sa et al., 2013), as symbolic assets for branding (Taecharungroj & Prasertsakul, 2023), or as marketing devices for differentiation (Calderwood & Davies, 2013; Gerosa, 2024). These local resources encompass not only physical materials but also intangible elements such as local knowledge, stories, and cultural practices (Woo et al., 2019). Building on conventional approaches, this study proposes new roles for local resources as materials that can be used to design creative community-anchored service experiences. Our findings demonstrate how local resources can become valuable design materials when reframed and transformed into multisensory experiential touchpoints.

In the Local Treasure strategy, proprietors can design interactive touchpoints by converting geographical features and community knowledge—such as neighborhood maps as personalized tools for exploring the local area at the guesthouse (P19); collaborative guidebooks as participatory narratives based on community knowledge at the perfumery (P16); and social media storytelling as shareable digital content based on neighborhood memories at the photo studio (P02).

In the case of the Celebration of Imaginative Stories strategy, the proprietors designed touchpoints using merchandise-based narratives as resources. For example, product labels were designed based on the stories of artisanal liquor makers (P21), and book collections were created based on profession-specific narratives in a botanical bookshop (P14). The value of such local artisan narratives as design materials lies in their contextual richness, enabling proprietors to create community-anchored experiences that could forge emotional connections between customers, products, and place (Suntrayuth, 2016; Williams et al., 2020).

To enhance proprietors’ design efforts in transforming local resources into experiential touchpoints for service experiences, design facilitators could take an active role in guiding the design process. They can start by introducing effective resource discovery methods, such as map-making workshops and community interviews (Ezzatian & AminZade, 2024; Jiang et al., 2020). These methods help proprietors collaboratively identify and uncover unique local stories and assets that they want to incorporate into their shops. By coordinating these activities, facilitators can enable shared interpretation and the co-creation of meaningful narratives rooted in the local context (Light & Akama, 2012). In addition to this, facilitators could offer tailored guidance on how to translate these narratives into tangible, multisensory touchpoints with designed-in local resources throughout the customer journey (Stare & Križaj, 2018).

Place-Related Experience

Place attachment can be intentionally cultivated through design interventions as a key design material for creating community-anchored service experiences, rather than as an emergent phenomenon of architectural features and social interactions stimulated by the space, as demonstrated by the extant literature (Ferreira et al., 2021; Hubbard, 2016; Maspul & Almalki, 2023).

Place attachment can be cultivated by designing spatial touchpoints, such as product arrangements, proprietor explanations, and social programs, that foster social connections and strengthen the emotional bond between customers and the shop (AbedRabbo, 2020; Rong, 2020). By interacting with such spatial touchpoints, customers can develop a deeper psychological connection to the space, leading to repeat visits, shared practices, and ongoing community participation (Cardinale et al., 2016; Haktanir & Gullu, 2024; Ujang et al., 2018).

In the Digging Ground strategy, for example, proprietors strategically designed experiential touchpoints such as interactive merchandise displays (P03), hands-on exploration zones (P03), and theme-based learning programs (P08, P13), transforming their shops into compelling destinations that enthusiasts continually seek out and wish to stay.

In the Village Salon strategy, the proprietors of a café (P07) and a wine bar (P09) designed community events and social programs to serve as a platform for the local community.

Here, design facilitators can help local shop proprietors intentionally design and operate structured, experiential touchpoints that encourage customers to continuously engage with the space through repeat visits, leave personal imprints, and build meaningful connections (Journée & Weber, 2016; Kitagawa & Candi, 2025; Woo et al., 2023). Facilitators could guide proprietors in designing these touchpoints not as one-off stimuli, but as a coherent sequence of interactions that promote ongoing participation and community bonding (Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2016).

Individuality-related Experience

Proprietors’ individuality influences emotional connections with customers and supports community building (Wilson & Hodges, 2022; Yoon, 2024). This study expands on this idea by proposing proprietors’ individuality as a design material that can be embodied in experiential touchpoints to create emotional resonance with customers. Proprietors’ personal philosophies and experiences can be transformed into narratives that foster a sense of belonging among customers in the shop.

In the Influencer-in-the-Wild strategy, proprietors’ individualities are expressed through spatial, material, and digital touchpoints—like shop facades (P17) and personal messages on receipts (P06)—to foster customer empathy and build an emotionally resonant community.

In contrast, the Pure Merchant strategy emphasizes everyday practices, such as regular menu changes, handwritten notes, stylized greetings, and personalized services, to establish trust-based relationships that naturally integrate into customers’ lives. In this way, proprietors’ individuality is designed through touchpoints not as something to be displayed, but as something to be empathized with and interacted with. As confirmed in actual cases (P05, P06, P07, P17), proprietors’ individuality functions as a catalyst for community building based on shared sensibilities and solidarity, beyond simple brand characteristics.

Facilitators can help proprietors reflect their individuality and values across service touchpoints through design activities (Anderson et al., 2025; Sinosich, 2019; Williams et al., 2020). By guiding proprietors in storytelling and touchpoint design, design facilitators can help proprietors create authentic, immersive experiences that foster customer empathy and strengthen community bonds. They could also provide expressive tools and platforms for proprietors to engage with their community (Ferreira et al., 2021), reinforcing trust and belonging through personalized interactions, capitalizing on their individual attractions.

Conclusions

This research has discovered the community-anchored service touchpoints and their deployment patterns of local shop proprietors. Furthermore, the roles of design facilitators were proposed in strategically creating social value for communities through unique and creative, community-anchored experiences.

First, a conceptual framework of community-anchored service touchpoints was established, categorized into two Community Anchors and seven Customer Enticements, based on the literature.

Second, the community-anchored service touchpoints currently used by the local shop proprietors were identified through in-depth interviews and on-site observations from 21 innovative local shop cases.

Third, a thematic analysis of the interview data was conducted to codify the touchpoints, which were then classified and entered into the framework. During the thematic analysis, another community anchor, Proprietor, in addition to Locality and Interest anchors already included in the framework, was newly discovered and duly added to the framework to serve as a new category by which the service touchpoints were classified, along with the existing categories.

Fourth, six strategic positions for service touchpoint deployment, including Local Treasure, Digging Ground, Influencer-in-the-Wild, Celebration of Imaginative Stories, Village Salon, and Pure Merchant, were discovered by cluster analysis upon the touchpoint deployment patterns of the local shop cases, finally converting their implicit strategies into explicit knowledge—the strategic community-anchored service touchpoint framework with six strategic positions that local shops could take according to their desired combination of three community anchors and seven customer enticements.

Based on the findings, three novel design materials for designing community-anchored service experiences were proposed: resources, place attachments, and the proprietor’s individuality. The study also provided design facilitation implications for each of these materials, offering guidance on how non-design experts can effectively transform these materials into meaningful service experiences.

The significance of this study lies in providing: 1) a strategic framework for local shops to develop community-anchored service experiences; 2) design materials and guidance for design facilitators to support local shops in co-creating innovative experiences. Strategic approaches to co-creating and deploying innovative community-anchored local shop experiences will contribute to a more vibrant and interconnected urban fabric, where local shops play a pivotal role in the economic and social life of the neighborhood. The research underscores the importance of collaborative efforts among local shop proprietors and design facilitators in shaping the future of urban communities.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the local shop proprietors for sharing their experiences through the interviews, which greatly informed this research.

References

- AbedRabbo, M. (2020). Exploring the connected town centre shopping experience and its implications on patronage intentions [Doctoral dissertation, Loughborough University]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.26174/thesis.lboro.12525575.v1

- Aguirre, M., Agudelo, N., & Romm, J. (2017). Design facilitation as emerging practice: Analyzing how designers support multi-stakeholder co-creation. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 3(3), 198-209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2017.11.003

- Anderson, K. C., Hass, A., Mertz, B. A., & McDonald, R. E. (2025). Super-heroes at your service: Navigating moral dilemmas and small business owner identity in online communities. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 35(4), 543-568. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-01-2024-0007

- Andres Coca-Stefaniak, J., Parker, C., & Rees, P. (2010). Localisation as a marketing strategy for small retailers. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 38(9), 677-697. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551011062439

- Asian Development Bank. (2023). Asia small and medium-sized enterprise monitor 2023: How small firms can contribute to resilient growth in the Pacific post COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Development Bank. http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/SGP230413-2

- Bennett, A. (2022). Gen Z and millennial shopping habits. UK POS. https://www.ukpos.com/knowledge-hub/gen-z-and-millennials-shopping-habits

- Benoit, K., Watanabe, K., Wang, H., Nulty, P., Obeng, A., Müller, S., & Matsuo, A. (2018). Quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(30), Article 774. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00774

- Bernard, H. R., & Ryan, G. (1998). Text analysis. In H. R. Bernard & C. C. Gravlee (Eds.), Handbook of methods in cultural anthropology (pp. 595-645). Altamira Press.

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299205600205

- Bitner, M. J., Ostrom, A. L., & Morgan, F. N. (2008). Service blueprinting: A practical technique for service innovation. California Management Review, 50(3), 66-94. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166446

- Björk, P., & Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. (2016). Local food: A source for destination attraction. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(1), 177-194. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2014-0214

- Bookman, S. (2014). Brands and urban life: Specialty coffee, consumers, and the co-creation of urban café sociality. Space and Culture, 17(1), 85-99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331213493853

- Broadway, M., Legg, R., & Broadway, J. (2018). Coffeehouses and the art of social engagement: An analysis of Portland coffeehouses. Geographical Review, 108(3), 433-456. https://doi.org/10.1111/gere.12253

- Burgess, S. (2002). Information technology in small business: Issues and challenges. In S. Burgess (Ed.). Managing information technology in small business: Challenges and solutions (pp. 1-17). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-930708-35-8.ch001

- Cadden, D. (2012). Small business management in the 21st century. Saylor Foundation.

- Calderwood, E., & Davies, K. (2013). Localism and the community shop. Local Economy, 28(3), 339-349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094212474870

- Cardinale, S., Nguyen, B., & Melewar, T. C. (2016). Place-based brand experience, place attachment and loyalty. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 34(3). https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-04-2014-0071

- Chaltas, A., Garcia-Garcia, M., Lobo, G., & Mittal, P. (2021, March 22). The retail rollercoaster: Riding the ups and downs of today’s omnichannel shopper landscape. Ipsos. https://www.ipsos.com/en/retail-rollercoaster

- Coyne, I. T. (1997). Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; Merging or clear boundaries? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(3), 623-630. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-25-00999.x

- Dessi, C., Ng, W., Floris, M., & Cabras, S. (2014). How small family-owned businesses may compete with retail superstores: Tacit knowledge and perceptive concordance among owner-managers and customers. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 21(4), 668-689. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-02-2014-0025

- Ezzatian, S., & AminZade, B. (2024). Co-design challenges: Exploring collaborative rationality and design thinking in the urban design process. CoDesign, 20(4), 763-780. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2024.2395360

- Faramarzi, S. (2021, May 17). Post-pandemic playbook: What Gen Z want from physical retail. Vogue Business. https://www.voguebusiness.com/consumers/post-pandemic-playbook-what-gen-z-want-from-physical-retail-adidas

- Ferreira, J., Ferreira, C., & Bos, E. (2021). Spaces of consumption, connection, and community: Exploring the role of the coffee shop in urban lives. Geoforum, 119, 21-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.12.024

- Florida, R. (2005). Cities and the creative class. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203997673

- Gatrell, J., Reid, N., & Steiger, T. L. (2018). Branding spaces: Place, region, sustainability and the American craft beer industry. Applied Geography, 90, 360-370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.02.012

- Gerosa, A. (2024). The hipster economy: Taste and authenticity in late modern capitalism. UCL Press. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/91226

- Goodwin, C., & Gremler, D. D. (1996). Friendship over the counter: How social aspects of service encounters influence consumer service loyalty. In T. A. Swartz, D. E. Bowen, & S. W. Brown (Eds.), Advances in services marketing and management (Vol. 5, pp. 247–282). JAI Press.

- Gorb, P., & Dumas, A. (1987). Silent design. Design Studies, 8(3), 150-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-694X(87)90037-8

- Guest, G., & McLellan, E. (2003). Distinguishing the trees from the forest: Applying cluster analysis to thematic qualitative data. Field Methods, 15(2), 186-201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X03015002005

- Gupta, S., & Vajic, M. (2000). The contextual and dialectical nature of experiences. In J. A. Fitzsimmons, & M. J. Fitzsimmons (Eds.), New service development: Creating memorable experiences (pp. 33-51). Sage.

- Haktanir, M., & Gullu, E. (2024). Place attachment in coffee shops: A customer perspective study in north Cyprus. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(1), 312-328. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-05-2022-0185

- Hubbard, P. (2016). Hipsters on our high streets: Consuming the gentrification frontier. Sociological Research Online, 21(3), 106-111. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3962

- Hult, K., & Scander, H. (2024). Hipster hospitality: Blurred boundaries in restaurants. Gastronomy and Tourism, 8(2), 65-82. https://doi.org/10.3727/216929722X16354101932474

- Jiang, C., Xiao, Y., & Cao, H. (2020). Co-creating for locality and sustainability: Design-driven community regeneration strategy in Shanghai’s old residential context. Sustainability, 12(7), Article 2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072997

- Ji, M. I. (2021). The fantasy of authenticity: Understanding the paradox of retail gentrification in Seoul from a lacanian perspective. Cultural Geographies, 28(2), 221-238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474020914660

- Journée, R., & Weber, M. (2016). Co-creation of experiences in retail: Opportunity to innovate in retail business. In Proceedings of the 8th world conference on mass customization, personalization, and co-creation (pp. 391-404). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29058-4_31

- Kallio, H., Pietilä, A., Johnson, M., & Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 2954-2965. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031