(Service) Design and Organisational Change: Balancing with Translation Objects

Anna Seravalli * and Hope Witmer

Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

This article contributes to the further understanding of how (service) design can engage with organisational change. It does so by applying translation theory and building on the insights from a 7-year-long collaboration with a public agency, during which three attempts at introducing new ways of working were carried out. Translation theory understands organisational change as an intentional and contingent process through which ideas are materialised in possible translation objects that intervene in organisational practices, structures, and assumptions. The longitudinal study highlights how to bring about change, translation processes, and the objects needed to balance the reproduction and challenging of existing practices, structures, and assumptions within organisations. Moreover, translation processes interact with existing power dynamics, which cause reactions to change interventions by, among other things, influencing the legitimacy and mandate of the processes. Therefore, in addition to the mobilisation of internal organisational knowledge, (service) design that engages with organisational change needs to be aware of both power dynamics and to develop approaches and sensibilities to be able to listen and respond to the consequences that interventions in these dynamics might create.

Keywords – Boundary Objects, Design in the Public Sector, Organisational Change, Service Design, Translation, Translation Objects, Waste and Water Management.

Relevance to Design Practice –The article suggests that, in engaging with organisational change, (service) design should (1) pay attention to how to balance between challenging and reproducing existing ways of working, assumptions, and structures in an organisation; (2) be aware of power dynamics and their influences and responses to processes aimed at organisational change; and (3) develop frameworks, approaches, and sensibilities to be able to listen and respond to the influences of power dynamics on design interventions.

Citation: Seravalli, A., & Witmer, H. (2021). (Service) Design and organisational change: Balancing with translation objects. International Journal of Design, 15(3), 73-86.

Received Oct. 15, 2020; Accepted Nov. 22, 2021; Published Dec. 31, 2021.

Copyright: © 2021 Seravalli & Witmer. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: anna.seravalli@mau.se

Anna Seravalli is a senior lecturer and design researcher at The School of Arts and Communication, Malmö University, Sweden. She has a background as product and service designer and holds a PhD in Design and Social Innovation. Her research engages with questions of participation and democracy in the strive towards the development of socially and ecological sustainable cities. She closely collaborates with citizens, NGOs, civil servants, and small entrepreneurs exploring possible design approaches and organizational models that might foster more sustainable, inclusive, and democratic cities. She is the coordinator of Malmö University DESIS Lab and boundary crosser at the Institute for Sustainable City Development.

Hope Witmer is associate professor in leadership and organization at the Urban Studies Department; she is the Director of the Leadership for Sustainability Master program; and researcher for the Center for Work Life and Evaluation Studies (CTA) and the Collaborative future making (CFM) research platform at Malmö University, Sweden. Research areas are: organisational resilience, power dynamics, sustainability, and inclusive organisational processes and structures including the development of the DOR (Degendering Organizational Resilience) model.

Introduction

The relationship between (service) design and organisational change has been widely explored, from reflecting on the impact of introducing service design in organisations (Buchanan, 2008; Deserti & Rizzo, 2014; Junginger, 2006; Kurtmollaiev et al., 2018) to articulating how service design can actively engage with organisational change (Junginger, 2015; Junginger & Sangiorgi, 2009). Similarly, the field of participatory design/co-design has recently been engaging with the question of organisational change (Agger Eriksen et al., 2020; Salmi & Mattelmäki, 2021).

Overall, these explorations highlight how design engagements with organisations need to consider existing legacies within organisations (Junginger, 2015) and how to intervene in relation to existing organisational artifacts, behaviours, norms, values, and assumptions (Junginger & Sangiorgi, 2009; Salmi & Mattelmäki, 2021). Kurtmollaiev et al. (2018) highlight that the adoption of design in an organisation requires both micro and macro changes, such as the introduction of new performance indicators, a renewed organisational language, and the facilitation of learning and experimentation processes among employees. Agger Eriksen et al. (2020) argue that to bring about changes in policy, learning processes that foster awareness about structures, routines, and their underpinning assumptions across operational and strategic levels need to be supported.

To articulate the dynamics between the existing organisational features and new ways of working, Kurtmollaiev et al. (2018) use institutional theory to show how the introduction of service design in a company not only impacts organisational logics but is also shaped by them. In a similar way, when using co-design processes to foster organisational change, Salmi and Mattelmäki (2021) found that change emerged from local meaning making driven by the employees, who negotiated between new ways of working and thinking and existing ones.

An emerging question is how designers can scaffold these negotiations. This demands a better understanding of the dynamics that emerge when new ideas and ways of working are introduced in an organisation: why do certain ideas get traction and others are dismissed? We,1 the authors of this paper, dwell on this question by using the notion of translation (Callon, 1984) and the way it is used to understand organisational change (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996; Czarniawska & Sevon, 2011). By bringing this concept into the design field, we want to explore how it can shed light on the dynamics that occur in design interventions in organisations and open up for how it can inform designerly frameworks and approaches that are attentive to the interaction between existing organisational logics and possible new ways of doing and thinking. This exploration is based on a long-term collaboration with a Swedish public organisation (SPO)—a collaboration aimed at introducing new ways of doing and thinking in the organisation. By reflecting on the longitudinal study, we develop an understanding of how (service) design can engage with the dynamics of translation.

Organisational Change as a Matter of Translation

Originally developed to describe how innovation comes into being (Callon, 1984; Latour, 1986, 1987), translation has also been used within organisational sciences (Wæraas & Nielsen, 2016) to understand organisational change (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996; Czarniawska & Sevon, 2011). In line with institutional theory, Czarniawska and Joerges (1996) understand organisational change as being shaped by both control and contingency—as in, intentional processes as well as the assumptions of the organisation and people within the surrounding context—and thus see the need for frames to articulate the dynamics between control and contingency.

Organisations can be viewed as social actors that respond to external conditions and operate internally based on a shared set of assumptions, structures, and practices2 (King et al., 2010; Schein, 2010). In addition to the people, organisations are also comprised of structures and formal systems. Therefore, they also include social dynamics, whereby a collective of people make order or sense out of their processes and experiences (Weick, 1995; Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007). With repetition, ways of acting and thinking become normative and create an organisational culture (Schein, 2010; Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007). The organisational culture becomes embedded as the right way to think and act expressed through organisational procedures, the people who are given positions of power, how resources are allocated, and the stories that get repeated (Ellström, 2010; Witmer, 2019).

The strength of these structures, practices, and assumptions lies in how they offer stability and a sense of shared identity and purpose (Kieser & Koch, 2008; Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007). The challenge is that as they become embedded, they construct a specific normative way of acting and thinking (Simon, 1991) and can hinder an organisation’s collective capacity to integrate new ways of working and thinking that are outside the normative shared understandings (Argyris & Schön, 1974; Leonard-Barton, 1992). However, organisations are not static—different parts influence each other internally. Moreover, they have permeable boundaries that take in and respond to the external context (Scott et al., 2007). This means that new ways of working and thinking can emerge from internal interactions and/or by the organisation being exposed to external ideas (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996).

In this view, organisational change can be understood as a matter of attempting to transform practices (i.e., the way people do things), structures (i.e., formal hierarchies, procedures, and documents that organise and legitimate practices); and assumptions (i.e., the values and beliefs that underpin practices and structures). It is a process informed both by intentionality and contingency (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996; Czarniawska & Sevon, 2011).

According to Callon (1984), translation is a collaborative effort that entails interactions among different actors as well as material artifacts; through such interactions, ideas are negotiated and appropriated thus leading to changes in assumptions and relationships. Using the concept of translation to understand organisational change entails highlighting its nature as a tentative alignment among different actors. In this alignment, ideas are not transferred but rather negotiated and appropriated by the participants according to their own background and conditions (Freeman, 2009). Moreover, the processual nature of translation shows how opportunities for change continuously emerge in the everyday activities of an organisation. Translation also highlights how organisational change is strongly connected to and affected by existing relationships among participants, which could be humans as well as existing structures. These power relationships can support or hinder opportunities for the materialisation of further ideas (Callon, 1984; Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996). Therefore, to reconstruct practices, structures, and assumptions demands engagement with organisational power dynamics. Within translation theory, there are primarily two approaches to power: one focuses on formal power structures, while the other views power as an offshoot of interrelationships within a social network (Frenkel, 2005). In this article, we combine these approaches and define power as something enacted through relationships, grounded in existing assumptions, and that shapes and is reproduced by practices and structures (Reynolds, 2014).

Designing in Translation

Within organisational studies, translation has been used to understand organisational change (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996; Czarniawska & Sevon, 2011). However, design is also interested in intervening in these processes. In order to achieve this, we turn to Callon’s (1984) original work on translation, which frames translation as a four-phase3 process. Moreover, we also consider the role of materiality in translation processes. Czarniawska and Joerges (1996) describe how new ideas need to be materialised in an object (i.e., a project, a document, a new routine, etc.) to be able to travel within and impact the organisation. Building further on these two perspectives, we understand the unfolding of translation as comprising these four phases: (1) problematisation, as in, exploring an idea (it could be a problem within the organisation but also an external opportunity) and the possible new practices and structures that it inspires (i.e., the formulation of a possible translation object; Callon, 1986; Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996); (2) negotiation of interests, as in, engaging potential allies who may have a stake in relation to the initial issue and/or the proposed practices and structures (Callon, 1986). To accommodate this, the possible translation object is further refined to respond to the potential allies’ different interests (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996). If the negotiation is successful, the (3) enrolment of allies follows, which entails that people in the organisation legitimise the translation object and commit to the reworking of current practices, structures, and assumptions in accordance with it (Callon, 1986; Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996). This is then followed by (4) mobilisation and change, in which allies engage in reconstructing current practices, structures, and assumptions, guided by the translation object.

Table 1. Translation phases (Callon, 1986; Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996).

| Problematisation | Negotiation of interests | Enrolment of allies | Mobilisation and change |

| Explore an idea and the possible new practices and structures (i.e., translation object) inspired by it. | Negotiate engagement of potential allies by refining the possible translation object. |

Legitimise the translation object and commit to the reworking of practices, structures, and assumptions. | Allies engage in reconstructing current practices, structures, and assumptions. |

Translation objects share some of the characteristics of boundary objects (Star & Griesemer, 1989; Star, 2010), which are concrete artefacts, representations, and concepts that engage people and groups with differing views. Boundary objects respond to the interests of several parties, but they are robust enough to maintain their own identity across domains. In a similar way, translation objects accommodate different interests while still being recognisable as one feature. Boundary objects are the stuff of action (Star, 2010), which means that they are both a part of practices and inform practices. Similarly, translation objects do not only carry a situated understanding about an idea but also a direction and space for action informed by this understanding (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996). Translation objects differ from boundary objects in that they do not only engage people and groups with differing views but also spark changes in the way people think, act, and organise themselves. To spark these changes, translation objects intervene in existing organisational power dynamics that produce and are reproduced by current structures, practices, relations, and assumptions. Among other things, these dynamics determine “the way in which actors are defined, associated and simultaneously obliged to remain faithful to their alliances” (Callon, 1984, p. 224) and thus influence legitimacy and mandate translation processes and their objects.

The design of translation objects can essentially be understood as a design problem, as it focuses on balancing tradition and transcendence (Ehn, 1988), or, in other words, how to intertwine existing and possible new practices, structures, and assumptions within an organisation. People within the organisation often possess knowledge about current practices, structures, and assumptions and the relationships between them, in addition to who and what contributes to their reproduction. This knowledge is often tacit and experiential and, to become actionable, it needs to be mobilised and communicated (Agger Eriksen et al., 2020; Vink et al., 2021). However, the articulation of this knowledge tends to expose frictions and inconsistencies (Argyris & Schön, 1974; Schein, 2010; Witmer, 2019), and therefore can be resisted by people and structures.

This preliminary understanding about designing for translation is further developed with insights from the longitudinal study.

Method

Translation originated within Actor-Network Theory, which looks at knowledge production as a process that is not neutral but rather always situated in a particular context and influenced by different interests (Latour, 2005). Based on this understanding, there is a preference towards engaging with situated contexts as a matter of developing a more nuanced understanding of how abstract concepts unfold in practice. In turn, this situated knowledge can be used to further advance general understandings (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996). In our work, we used a reflexive dialogue (Ferguson, 2022) between ourselves and our two disciplines—design and organisational studies—to unravel a long-term collaboration with a public organisation (SPO), which relied on a close engagement between researchers and SPO representatives. The collaboration comprised three different projects in a longitudinal study that applied a participatory design (PD) methodology, according to which co-design processes can be used to bring together different people and their agencies and perspectives to address a possible challenge and collaboratively learn about it (Simonsen & Robertson, 2012). The three projects were structured as co-design processes which aimed at introducing new ways of working with SPO and engaged SPO representatives, design, and other fields researchers. In line with PD, rigour in the projects was achieved by consistently involving SPO representatives in collecting, analysing, and reflecting on the data. Each project had a project team consisting of researchers and SPO representatives. Projects also included meetings and interviews with other SPO representatives, with the aim of proving and further developing insights developed by the project team. More specifically, each project used workshops, joint meetings, and collaborative prototyping to mobilise SPO representatives’ implicit knowledge about the organisation and intertwine it with theoretical knowledge provided by researchers. Moreover, SPO participants were also engaged in analysing the data and reflecting on the outcomes of the projects over time. Additionally, interviews were conducted at the beginning and end of each project with the people involved and other SPO representatives for the purpose of tracing and collaboratively analysing if and how the project activities impacted organisational practices, structures, and assumptions (see Table 2). All three projects led to different concrete outcomes (see Table 2) and impacted the organisation in different ways.

To understand how translation unfolded in and across the three projects, we, the researchers, carried out a meta-analysis of the data and outcomes of the three projects (Table 3). In particular, we created two digital maps to organise insights in relation to each project. The first one focused on changes in relation to practices, structures, and views, and the second one focused on the different phases of the translation process, as outlined in Table 1. To compile the maps, we carried out a reflexive dialogue (Ferguson, 2022) that engaged our different disciplinary and experiential backgrounds in taking a critical distance from our preliminary reflections and personal and emotional engagement with the unfolding of the three projects.

Table 2. Methodological details of the three projects.

| Project 1: RT the service pilot (2014-2017) |

Project 2: New procedure for service development (2018) | Project 3: Digitalisation Lab at SPO (2020-2021) | |

| Project team | First author (design researcher), RT project leader, and RT head of operations. | First author (design researcher), a researcher in public policy, and RT project leader. | First author (design researcher), second author (organisational studies researcher), and the lab manager. |

| Other SPO people involved |

Employees from the operation units. Manager of planning and development unit, manager of the waste department, employees and the manager from the communication department, SPO’s CEO. | Employees from operation, planning and development, and finance units; managers of the planning and development, finance, and operations unit; manager of the waste department; head of SPO research; head of the communication department; and head of organisational development unit. | Lab board: head of SPO research, head of the organisational development unit, head of the strategy and development unit, one employee from the communication department. Others: employees involved in the evaluation of project applications, applicants, applicants’ bosses, SPO’s CEO. |

| Data collection activities done by project team |

Collaborative prototyping of the service, weekly planning and evaluation meetings, and monthly reflective meetings with representatives from different organisations involved in the pilot. Two workshops with representatives from different organisations involved in the pilot and their managers, and SPO responsible managers. Interviews with different SPO managers at the beginning and one month after the pilot ended to analyse if and how learnings from RT spread within SPO. |

Three workshops with employees from different units. Two meetings with the head of the planning and development unit. Two meetings with all managers of the waste department. Two open meetings to present the proposal to the head of SPO research, the head of the communication department, and the head of the organisational development unit. |

Four workshops/meetings with the lab board. Initial interviews with lab board members and SPO’s CEO on the topic of innovation. Formulation of the call for ideas and the application form. Observation of the evaluation meetings and the meetings with the lab board. Two kick-off workshops with lab applicants. Interviews with the unit managers who became engaged in the process with a focus on innovation on a unit level. |

| Analysis driven by the project team |

Collaborative mapping and clustering of data from the activities’ documentation, workshops, and interview transcripts. Analysis of internal documents regarding formal decisions about RT pilot after the end of the project. |

Collaborative mapping and clustering of data from workshops and meetings. Four meetings to analyse preliminary results with the head of the planning and development unit at the waste department. One open meeting to present the final proposal to the employees and collect their feedback. One meeting with the head of the planning and development unit to refine the final proposal. |

Collaborative mapping and clustering of data from applications and interviews with different managers. These preliminary findings were integrated with observations during the meetings and input gathered during the kick-off workshops, carried out mostly by the researcher with some input from the lab manager. Three meetings to discuss preliminary outcomes of the lab evaluation with the researchers and the lab manager (one meeting included a member of the evaluation group, and one meeting the head of research at SPO). Two meetings to discuss the outcomes of the evaluation of the lab with the lab manager and the lab board members. |

| Outcome | A report about learning in the development of RT. | A proposal for a new procedure for service development. | An evaluation of the lab process to date and suggestions for how to continue with lab activities. |

Table 3. Details of the meta-analysis carried out by the two authors of this paper.

| Project 1: RT the service pilot (2014-2017) |

Project 2: New procedure for service development (2018) | Project 3: Digitalisation Lab at SPO (2020-2021) | |

| Data | Interviews at the beginning and the end of RT project. | Formal documents about project outcomes, new function established within the unit together with one employee who participated in the project and with the head of the planning and development unit. | Initial interviews with the lab board and the unit managers, presentation of the lab results as presented by the lab manager, and video and written recordings of the meetings with the lab board and the project manager about the lab evaluation. |

| Analysis | Two digital maps to organise insights about organisational change and the translation process in the three projects carried out through a reflexive dialogue between the two authors. | ||

Study

The study context is the Swedish public sector—in particular, waste and water management.

Sweden, as with other Western countries, has a growing interest in introducing new ways of working in the public sector (SOU, 2013). The rationale is that contemporary societal issues require new ways of acting and organising that are based on the following principles: strengthening a user/citizen perspective; introducing a broader/long-term perspective; collaborating across public organisations and with other societal actors; and nurturing trust-based leadership that favours experimentation over control. Several actors promote these ideas, for example, the Swedish Innovation Agency, which financed innovation platforms for city development (Zingmark, 2016), and the Association of Swedish Municipalities and Regions, which developed an innovation guide and is driving learning processes about innovation in the public sector (SKR, 2021).

It is in this context that the collaboration with SPO developed. SPO is a cross-municipal organisation that manages waste, drinking water, and wastewater in eight municipalities and provides services to approximately 800,000 people. Water and waste management are traditionally framed as a matter of creating and maintaining efficient and safe technical infrastructures (Corvellec & Czarniawska, 2014; Gleick, 2000). However, there has been a recent growing recognition that water and waste management also includes social aspects (for example, related to fostering behavioural change among final users), and this requires coordination and joint action with other societal actors (for example, to effectively react to a more unpredictable climate; to encourage waste minimisation; and to reduce water wastage). This shift calls for new ways of understanding, practising, and organising water (Pahl-Wostl et al., 2011) and waste management (Corvellec & Czarniawska, 2014).

Project 1 (2014-2017) was a pilot for a new waste prevention service (RT), an initiative of the SPO waste department that relied on internal and external financing. The project engaged an RT project leader and staff, users of the service, civil servants focusing on neighbourhood development, the regional company handling waste processing, and the first author (a design researcher). RT was the first project in which SPO engaged in developing a new service rather than copying one from another organisation. The project also aimed at testing the use of design and co-design approaches (like prototyping and formats for citizens’ and actors’ engagement), which were new to SPO. The functions of the service were progressively refined by prototyping different elements and evaluating them with the staff, the users, and the other involved actors during regular monthly workshops that aimed at reflecting on the development of the service, any emerging problems, and how they could be addressed. The workshops engaged RT staff, an RT project leader, some of her colleagues, local civil servants, and representatives for local initiatives. The responsible managers at SPO joined these workshops only a couple of times and mainly relied on the RT project leader to report back about the project. RT was very well received by the users and local actors who expressed an appreciation for how RT combined waste prevention with local concerns regarding the need for meeting spaces and social activities. Ten months after its opening, the responsible managers (the head of the waste department and the head of the waste planning and development unit) decided to terminate RT because the project was too demanding for SPO in relation to questions of staffing and work environment. This decision was unexpected for the RT project leader, and it was strongly contested by users and local partners, who later convinced SPO managers to reconsider their decision and work together with them to find a solution to keep RT going. This led to the redistribution of formal responsibilities among different city departments and other partners. At the end of this reorganisation, the head of SPO’s waste planning and development unit quit her job.

One month after the pilot interruption, the first author and her colleague carried out interviews with several SPO representatives. Through these interviews, it became apparent how the RT project leader developed new ways of working and thinking about service development and how these new learnings did not spread in SPO. The RT project leader stated:

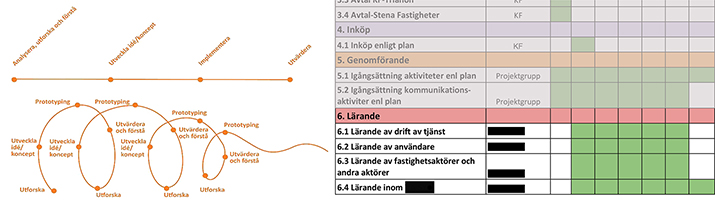

Many issues with RT emerged while we were driving the pilot, and it was not possible to foresee them when planning it. I was used to working with planning first, and then implementing, but through RT, it became clear that is not a good way of working for creating new services. We need to test and learn together with other actors while driving pilots (….). I won’t go back to the traditional way of driving projects.4 (see Figure 1)

Figure 1. Snapshots from a project plan for a service development process in which RT project leader presents (left) how she will use a prototyping project development rather than usual project development. The project activities list (right) includes learning sessions with several partners.

The head of the planning and development unit had a completely different perspective: “I think we started too early with the pilot—more planning would have been needed to sort out questions of responsibility over the running of the service”.5 The head of the waste department added, “RT has been very successful in engaging citizens and other actors. However, it failed in delivering what we need: a standard service concept that can be just easily implemented in several neighbourhoods”.6 This view was shared by the head of the communication office and SPO’s CEO.7 In reflecting on the gap between her and the SPO’s managers view on the pilot, the RT project leader stated, “If I could go back, I would use the meetings I had with my head of unit and the head of department in a different way: instead of focusing on details on the running of the pilot, I would rather engage them in reflecting together on the process.” 8 [see Seravalli et al. (2017) for more about this project].

Project 2 (2018). The gap between the project leader and managers’ view on RT echoed the situation of other projects in the department.9 The RT project leader learned that other colleagues experienced that the current project management procedures were ill-equipped to deal with more complex projects. The RT project leader, together with the first author, proposed to the head of the waste department to apply for financing to develop Project 2, which focused on the SPO waste department’s capacity to deal with complex projects. The head of department agreed to this proposal. The project was an externally financed, 6-month-long project that aimed at formulating a proposal for a procedure and organisational structure for the development of new services.

Internally, resources were allocated for employees to participate in the project. The project team comprised the RT project leader, the first author, and a public administration researcher. The project engaged employees of the waste department units (operations, planning and development, and finance), their managers, and the head of the department. During the kick-off with the managers, it was decided that only the new head of the planning and development unit would participate, as the other two managers explained that they were too busy to engage in the project. The new head of the planning and development unit came from the city street department and had experience dealing with complex innovation projects. During the course of the project, the head of the waste department quit her job.

The project engaged employees from different units by analysing previous projects to identify challenges and opportunities. The project team facilitated the process and the researchers contributed with theoretical input about design and public policy. On the basis of this analysis and with support from the project team, the employees sketched a preliminary proposal for a procedure and structure for the service development. The proposal was then refined by the project team which engaged the new head of the development and planning unit in discussing the input from the employees and in the shaping of the proposal. Among other things, the new head ensured the proposal resonated with SPO’s general project model by, for example, positioning decision gates in the proposed procedure.

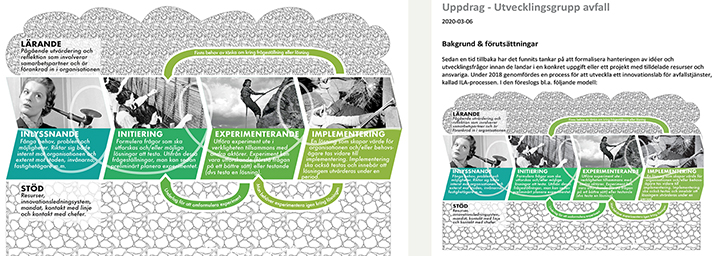

Throughout the project, the following challenges were identified: difficulties in managing external requests for new services, issues with handling collaborations with other actors, lack of competencies for working with citizens’ engagement, difficulties in transforming pilots into ordinary services, and the lack of organisational support for innovative processes. The proposal addressed these challenges by suggesting a designerly inspired process that entailed collaborative experimentation and learning, iteration, and the flexible allotment of resources. On the organisational level, the proposal pointed to the involvement of representatives from different units and engaging managers in joint reflection and decision making along the way. The proposal was presented by means of text and an infographic that showed the different phases of the procedure (Seravalli et al., 2019).

The proposal has been partially implemented through the establishment of a listening group. The listening group brought together representatives from the three units within the department (operations, finance, and planning and development) to collect problems and ideas about current and possible new services. This input is collaboratively analysed by the group who formulates proposals for the managers about how to prioritise and follow up on the problems and ideas.

In the interviews that occurred 1.5 years after the project ended, the employee who participated in the project and who is now responsible for the listening group stated,

The listening group is based on the outcomes of the project, which has been focusing on the issues that have been discussed among us (employees) for several years (…) The project gave us the space to discuss innovation issues across units (…) It was a pity that it didn’t involve all department managers.10 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The infographic developed within the project (left) depicts the procedure for project development and a snapshot (right) from the official description of the listening group that uses the infographic to explain the origins and goals of the group.

The head of the planning and development unit stated,

The proposal (developed in Project 2) has become my mental model to think about innovation projects. At the moment, I am working further to promote it as a model for innovation projects for the entire SPO.11

She also added,

The project was a bit controversial at that time. The organisation wasn’t ready for it…but now, it’s not controversial anymore…since it aligns with the new strategy…however, it would have been better if the other department managers would have joined the project as well.11

Project 2 was well received also by SPO managers outside the waste department, who recognised how it aligned with the new strategy that was launched while the project was running. The head of communication, in particular, who was assigned the role of establishing an innovation lab for the entire SPO, wanted to continue the collaboration with the first author.

Project 3 (2020-2021) aimed at designing SPO’s overall innovation lab. External financing was used to cover the engagement of the first and second author. The idea was to apply a similar approach as the one used in the second project but on a broader scale. However, these plans had to be revised as both the SPO CEO (who was key in formulating the new strategy) and the head of communication (who was responsible for the innovation lab) left their position before the project started. The person responsible for SPO research put together a group that could act as the governing board for the lab, which included himself, the head of the strategy and development unit, the head of the organisational development unit, and one person from the communication unit. After some months, the lab board suggested to the SPO executive board that resources be allocated for 2021 to develop a digitalisation lab as the first innovation lab activity. The digitalisation lab consisted of financial resources that employees could apply for (with the approval of their unit managers) to develop digitalisation projects to improve organisational efficiency. The idea was to encourage employees’ creativity and propension to innovation as well as provide resources for employee generated projects. The digitalisation lab aligned with the senior management views of innovation that was framed as a matter of developing new solutions by working with agile-inspired approaches to improve economic efficiency.12

A new lab manager was temporarily hired (one year position). She had experience in working with water management issues in city development projects. She led the process with support from the board and with the involvement of colleagues from other departments for assessing the applications. We, the two authors, were put in charge of evaluating and suggesting improvements for the lab. The digitalisation lab received project applications from seven out of eight departments, which was considered a success. The proposed projects were mostly about improving current ways of working through digitalisation with a focus on maintenance and monitoring. The applications included both new projects as well as support to existing projects, mainly originating from single units with some collaborations across SPO and a few external collaborations. During the evaluation phase, it was identified that some of the applications were overlapping with current ongoing projects. It also emerged that agile ways of working and a focus on economic efficiency were not relevant for all units’ situations and goals. In the interviews with the unit managers who had employees applying to the lab, it was identified that most of the involved units had existing internal routines to work with innovation and development. Moreover, the involved unit managers highlighted lack of collaboration across units and departments as a key problem. As one of the unit heads put it, “We do not need high-end digital solutions, we need new ways of working (…) we lack coordination across units”.13 Another unit head stated, “We need to get innovation efforts within the operations, so that it doesn’t become an isolated activity that a small group of employees works with”.14 The need for internal collaboration was also highlighted by all board members in the first round of interviews we conducted.15 By analysing the process and the input from the unit managers, we identified that digitalisation efforts at SPO suffered from a lack of collaboration and a shared prioritisation based on the final users’ and operational needs rather than on new ideas about how digital tools could be used to improve current ways of working.

Towards the end of project 3, we presented these insights to the lab manager and the board. During the first presentation, it turned out to be difficult to engage them in relating to and reflecting on these insights. On the basis of the preliminary evaluation made by the lab manager, their focus for 2022 was on attracting more radical innovation projects and on mobilising more employees. We, with the lab manager and SPO’s head of research, reworked the presentation of the results. A new section that focused on key characteristics of innovation in the public sector was added to the final evaluation. In this section, the importance of trying out new things was paired with the importance of collaborating within and outside organisations and of prioritising based on the public good and operational needs. In the last meeting with us, the board representatives stated that this new section was important in framing our findings, and they engaged in discussing questions of collaboration and prioritisation with us based on the results of the project.

Table 4. Timeline of the study.

|

|

|

| Project 1, RT the service pilot |

|

|

| Project 2, New procedure for service development |

|

|

| Project 3, Digitalisation lab at SPO |

|

|

Analysis

All three projects can be considered potential translation processes given that they had the intention of introducing new ways of working in SPO. The analysis of each project focuses on (1) what was translated, how, and what consequences did it have on SPO’s practices, structures, and assumptions; (2) the role of possible translation objects; and (3) the unfolding of power dynamics by looking at legitimacies and mandates in each project.

Project 1, RT the Service Pilot: New Practices and Assumptions and Limited Influence

In the interviews after the pilot interruption, it emerged how the RT project leader appropriated designerly practices and views. However, there were no apparent changes in current structures or assumptions within the department.

The pilot entailed a problematisation and negotiation of interests among different actors about waste reduction in relation to social sustainability, which, in turn, shaped RT. This process culminated when SPO managers decided to interrupt the pilot resulting in the mobilisation of external actors to save RT. However, the process lacked the enrolment of the department managers, as highlighted by the final interviews, in which it clearly emerged how RT and its development did not fit their assumptions nor SPO’s existing structures for project management.

The project leader and the other actors involved collaboratively shaped RT so that it provided a situated understanding, a space, and direction for how to combine waste prevention with social sustainability concerns. It also included practices and assumptions about how to implement a service, and thus it was a potential translation object for SPO. However, it only achieved translation with the RT project leader, and for the SPO managers RT became a foreign object.

The process overlooked the importance of sustaining the enrolment of the managers, and, therefore, RT lost legitimacy and a mandate from the managers along the way. According to the RT project leader, enrolment could have been ensured by engaging the managers in a reflective process.

Project 2, New Procedure for Service Development: New Practices, Structures and Assumptions

The second project challenged the assumptions supporting current procedures for service development and project management. It also opened up opportunities for a different perspective (service development as an iterative and collaborative process involving people within and outside the department and based on shared prioritisation across units). This perspective was partially enacted through the creation of a new structure for project management—the listening group.

The project engaged both the employees and the head of the planning and development unit in developing a shared problematisation about current service development procedures based on their experiences. With support from the researchers, it was possible to negotiate different interests and to develop a proposal that both parties could relate and commit to, leading to their enrolment. The creation of the listening group can be looked upon as the result of the joint mobilisation of employees and the manager to create new structures and practices in the department.

The final proposal became a translation object for the employees and the unit head, which also opened negotiations with other managers and people within SPO. The proposal provided a situated understanding space and direction for a different way to practice and organise project management, which connected to current procedures and structures for project management at SPO.

As testified by the interview with the employee, the project responded to a shared concern among employees and thus obtained their legitimacy and mandate. It also had some formal legitimacy through the enrolment of the new head of the planning and development unit. A support that was potentially weakened by the withdrawing of the two other managers from the process. However, the alignment of the proposal with SPO’s new strategy provided further legitimacy to the project, as testified by the involved manager.

Project 3, Digitalisation Lab at SPO: New Structures but No Changes in Practices or Assumptions

The third project led to changes in structures through the establishment of an innovation lab. Its first activity, the digitalisation lab, tended to reproduce rather than challenge current practices and assumptions in the organisation, given that it engaged people and units who were already working with innovation.

The digitalisation lab aligned with SPO senior managers’ assumptions about innovation with a focus on bottom-up projects, agile ways of working, and economic efficiency. During the analysis of the lab activities, it emerged how this problematisation led to the enrolment and mobilisation of units and employees who were already working with innovation, and thus, not really fostering new practices or assumptions in SPO. The lab contended with issues about internal collaboration and prioritisation. The importance of these issues for innovation work was raised in the interviews with the participating unit managers and the representatives of the board. However, they were initially not seen as something the lab could or should focus on, as testified by the preliminary plans for 2022. The researchers’ analysis opened up the opportunity for a re-negotiation by presenting the importance of collaboration and prioritisation for innovation in the public sector. At the moment, it is too early to see possible developments of such re-negotiation.

The digitalisation lab turned out to be a boundary object rather than a translation one, as it brought together people across the organisation providing a concrete understanding, space, and direction to work with innovation. However, to do that, it mostly relied on strengthening existing practices, alliances, and assumptions rather than challenging them.

The alignment with senior management assumptions about innovation was key in the beginning to ensure the legitimacy and mandate for the lab. Participation across departments gave further legitimacy to the initiative. The digitalisation lab was the very first activity of the innovation lab, and it was fully financed with internal resources, as decided by the SPO executive board. Therefore, it was a highly visible project. That the initial assumptions about innovation were restated for 2022, despite evidence about the importance of collaboration and prioritisation, hints towards the fact that the lab and the people involved with it were operating from a position that was too precarious to challenge the status quo (e.g., the lab manager was new to SPO and was operating on the basis of a temporary contract).

Table 2. Methodological details of the three projects.

| Project 1: RT the service pilot |

Project 2: New procedure for service development | Project 3: Digitalisation Lab at SPO | |

| What was translated and how |

RT project leader appropriated designerly and co-designerly practices. Her assumptions about project management changed. The project did not affect SPO’s structures or managers assumptions. The project negotiated with, enrolled and mobilised RT project leader and external partners but did not enrol SPO’s managers. |

The project led to new practices, structures, and assumptions within the waste department (i.e., the listening group) that responded to employees’ and the manager’s perceived limits of traditional project management. The project negotiated with, enrolled, and mobilised the employees and the manager about the shared understanding of the limitations of traditional project management and how these could be overcome. |

A new structure within SPO (i.e., the innovation lab) was created to foster new practices and assumptions. The digitalisation lab’s focus was on bottom-up projects, agility, and efficiency. The lab mobilised units that were already working with innovation. The project tended to reproduce existing practices and assumptions within SPO. The process negotiated with and enrolled employees and managers across the organisation who were already working with innovation and development. |

| The role of the object |

The pilot became a translation object for the RT project leader. For SPO’s managers, it became a foreign object. | The proposal was a translation object among employees and the head of the planning and development unit. | The lab was a boundary object between senior management, employees, and other managers in the organisation who are already working with innovation. |

| Power dynamics: legitimacy and mandate | RT lost legitimacy and the mandate from the managers. | Legitimacy and mandate were ensured by the close involvement of employees and the head of the planning and development unit, and by the alignment with the new SPO strategy. | The lab obtained legitimacy and mandate by aligning with and reproducing senior management’s and some units’ assumptions and practices about innovation. High expectations. Precarious position of the project leader. |

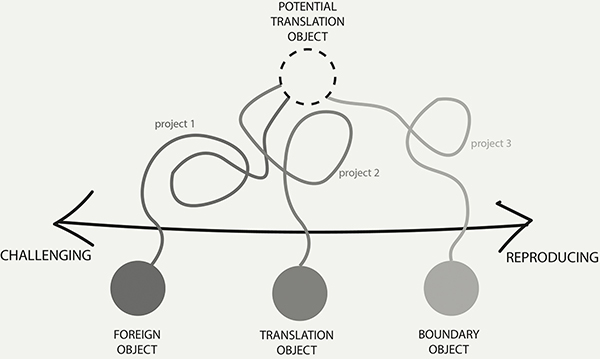

Balancing with Translation Objects

Even though all three projects had the ambition of bringing about some kind of change at SPO, their outcomes were very different. The service pilot (Project 1) became a foreign object, too far removed from underlying assumptions about and structures for project management to be open to the possibility of reworking current procedures. The proposal for a new service development procedure (Project 2) became a translation object shaped by employees, one manager, and the researchers. They interweaved new assumptions, possible practices and structures about project management and service development with existing ones, leading to the creation of a new structure (the listening group) and introducing new practices for project management. The digitalisation lab (Project 3) became a boundary object, which engaged different managers and employees by mostly reproducing and supporting their current assumptions and practices about innovation.

Overall, the three projects highlight the importance for translation processes and their objects of balancing between tradition and transcendence (Ehn, 1988), in other words, aligning with existing interests and thus reproducing current practices, structures, and assumptions, while concurrently challenging these aspects so that new opportunities can emerge (Figure 3). The three projects balanced challenging and reproducing in different ways, which led to different outcomes.

Figure 3. The three projects and their outcomes.

The longitudinal study confirms the importance of awareness about and the activation of internal organisational knowledge for being able to navigate this delicate balance (Agger Erisken et al., 2020; Salmi & Mattelmäki, 2021; Vink et al., 2021). It also provides examples of what kind of difficulties can be met in this activation (Argyris & Schön, 1974; Schein, 2010; Witmer, 2019), like in Project 2, with the withdrawing of the two managers from the project.

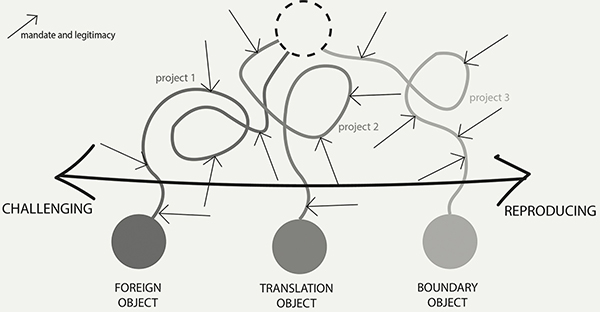

…While Listening and Adapting to Power Dynamics

The shaping of possible translation objects is influenced by existing power dynamics. These dynamics shape and are reproduced by current assumptions, practices, and structures in an organisation (Reynolds, 2014) and, as previously identified, they influence, among other things, the legitimacy and mandate of translation processes and their objects (Callon, 1984).

Evidenced in the study was the role of both formal and informal power structures and relations (Frenkel, 2005) in determining legitimacy and mandate. In the service pilot (Project 1), the loss of the managers’ legitimacy and mandate entailed losing the possibility to engage with current SPO project management structures. However, the challenges that emerged in Project 1 resonated with the concerns of other SPO project leaders. As a result, Project 2 (new procedure for service development) could rely on employees’ legitimacy and mandate as testified by their engagement in the project and in the implementation of some of its outcomes. In the digitalisation lab (Project 3), the alignment with senior management’s and other employees’ views on innovation not only ensured broad legitimacy and mandate for the digitalisation lab but also meant that the initiative tended to reproduce rather than challenge current assumptions and practices about innovation.

In the study, gaining and losing legitimacy and mandate emerges both as the result of intention and contingency (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996). In Project 2, without the new organisational strategy, it might have been difficult to implement the listening group. One can also speculate about what would have happened if the head of department had not resigned in the middle of the project. Similarly, in Project 3, the resignation of the CEO and the person originally responsible for the lab led to the temporary employment of an external person to run the lab, someone who had little knowledge about SPO and operated from a precarious position.

The study well exemplifies the complexity of navigating questions of legitimacy and mandate, and, in turn, power relations. Translation processes need support from several directions in order to be able to engage with practices, structures, and their underlying assumptions—support that is not found once for all but rather needs to be continuously considered as the process unfolds. Moreover, to strive towards multiple legitimacies and mandates may also mean losing the capacity to challenge the status quo, and thus achieving translation (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Mandate and legitimacy shape possible translation processes and the way they balance challenge and reproduction.

In light of this, we suggest that, in balancing reproduction and challenge, continuous attention should be given to power dynamics. However, it is important to remember that power dynamics are often difficult to expose (Argyris & Schön, 1974; Schein, 2010; Witmer, 2019) and, as it emerges in the study, they are also further shaped by other contingencies (Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996). Thus, organisational power dynamics are not fully intelligible as such, but rather, it is possible to observe their influence on and reactions in the unfolding of possible translation processes, for example, by following how legitimacy and mandate are gained or lost, as we did with the study.

Turning back to (service) design and its engagement with organisational change, our suggestion is that particular attention should be given to power dynamic manifestations in structures, processes, and relations. In addition to the use of theoretical frameworks like translation that can help in articulating power dynamic influences and reactions, there is the need for developing approaches and sensibilities to be able to listen to how power dynamics talk back (Schön, 1984) to a design intervention in an organisational context and to engage with these reactions.

Conclusions

Translation frames organisational change as an intentional and contingent process through which ideas materialise into translation objects that bring about change by intervening in practices, structures, assumptions, and power dynamics within an organisation (Czarniawska &, Joerges 1996). We use translation to further inform the understanding of (service) design processes that aim at introducing new ways of working in organisations. Particularly, by building on Czarniawska and Joerges (1996) and Callon (1984), we frame translation as a process that shapes translation objects and that requires balancing the reproduction and challenges (Ehn, 1988) of current practices, structures, and assumptions. Through the lens of translation, we analysed three different consecutive projects which aimed at introducing new ways of working within the same public organisation and had very different outcomes. The analysis confirms that, in order to balance reproduction and challenge, there is the need to mobilise internal organisational knowledge (Agger Erisken et al., 2020; Salmi & Mattelmäki, 2021; Vink et al., 2021). Moreover, translation processes are influenced by and intervene in power dynamics (Callon, 1984; Czarniawska & Joerges, 1996) which, among other things, influence the legitimacy and mandate of translation processes. Therefore, in engaging with organisational change, (service) design needs to develop an awareness of power dynamics as well as approaches and sensibilities to be able to listen and respond to the consequences that intervening in these dynamics might create.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to SPO for our long-term engagement and to all the people who were involved in the projects. We are particularly grateful to RT project leader who made possible and strongly engaged in this collaboration. Thanks to the researchers, Metter Agger Eriksen and Heiti Ernits, who were part respectively of Projects 1 and 2. This article has been written with financing from FORMAS, project number 2019-02037.

Endnotes

- 1. As the paper unfolds, several collectives will turn up. It is therefore important to specify that we always refers to the two authors of the paper.

- 2. Here, practices are understood out from the design and participatory design tradition. They refer to ways of doing that emerge from experiences and reflection in and on such experiences (Schön, 1984). Practices are the outcome of professionals’ ongoing efforts to adapt general theories and formalised procedures to attend to and to be able to act in a complex reality. Practices are often shared within communities (e.g., professional groups and/or organisations), and they ground and are grounded in the values and identities of such communities (Lave & Wegner, 1991).

- 3. Callon (1986) identifies four phases in translation: (1) problematisation, as in, the formulation of an issue and the network of actors and objects around it; (2) interessement, as in, the negotiation through which possible shared interests among actors are negotiated; (3) enrolment, as in, the alliances that might emerge if interessement is successful; and (4) the mobilisation of allies, as in, the ability of the enrolled actors to introduce new ideas and practices in their own networks by mobilising actors and objects and reworking given relationships among them.

- 4. Interview with RT project leader immediately after the pilot interruption, 04/10/2016.

- 5. Joint interview with the head of the waste planning and development unit and the head of the waste department right after the pilot interruption, 06/10/2016.

- 6. Joint interview with the head of the waste planning and development unit and the head of the waste department immediately after the pilot interruption, 06/10/2016.

- 7. Interviews with the head of communication and SPO’s CEO, 07/10/2016.

- 8. Interview with RT project leader immediately after the pilot interruption, 04/10/2016.

- 9. Conversations between the first author and RT project leader in autumn 2016 and spring 2017.

- 10. Interview with one of the participants to the second project who is now responsible for the listening group, 03/03/2021.

- 11. Interview with the head of planning and development unit at the waste department, 03/03/2021.

- 12. Interview with SPO’s CEO, 27/08/2020.

- 13. Interview with the head of the project unit (working with the maintenance, preparation, and upgrading of SPO’s plants), 11/05/2021.

- 14. Email from the head of one of the production department units to the head of the strategy and development unit, autumn 2020.

- 15. Individual interviews about the topic of sustainability, learning, and innovation at SPO were carried out with the four members of the lab board in spring/summer 2020.

References

- Agger Eriksen, M., Hillgren, P. A., & Seravalli, A. (2020). Foregrounding learning in infrastructuring—To change worldviews and practices in the public sector. In Proceedings of the 16th Conference on Participatory Design (Vol. 1, pp. 182-192). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3385010.3385013

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. A. (1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-bass.

- Buchanan, R. (2008). Introduction: Design and organizational change. Design Issues, 24(1), 2-9. http://doi.org/10.1162/desi.2008.24.1.2

- Callon, M. (1984). Some elements of a sociology of translation: Domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. The Sociological Review, 32(1), 196-233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1984.tb00113.x

- Corvellec, H., & Czarniawska, B. (2014). Waste prevention action-nets. In K. Ekström (Ed.), Waste management and sustainable consumption. London, England: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315757261

- Czarniawska, B., & Joerges, B. (1996). Travels of ideas. In B. Czarniawska & G. Sevón (Eds.), Translating organizational change (pp. 13-48). Gothenburg, Sweden: Gothenburg University. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110879735.13

- Czarniawska, B., & Sevón, G. (Eds.). (2011). Translating organizational change (Vol. 56). Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter.

- Deserti, A., & Rizzo, F. (2014). Design and organisational change in the public sector. Design Management Journal, 9(1), 85-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmj.12013

- Ehn, P. (1988). Work-oriented design of computer artifacts (Doctoral dissertation). Umeå University, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Ellström, P. -E. (2010). Practice-based innovation: A learning perspective. Journal of Workplace Learning, 22(1), 27-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665621011012834

- Ferguson, K. (2022). Agonistic navigating: Exploring and (re)configuring youth participation in design (Doctoral dissertation). RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia.

- Freeman, R. (2009). What is ‘translation’? Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 5(4), 429-447. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426409X478770

- Frenkel, M. (2005). The politics of translation: How state-level political relations affect the cross-national travel of management ideas. Organization, 12(2), 275-301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508405051191

- Gleick, P. H. (2000). A look at twenty-first century water resources development. Water International, 25(1), 127-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060008686804

- Junginger, S. (2006). Organizational change through human-centered product development (Doctoral dissertation). Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA.

- Junginger, S. (2013). Design and innovation in the public sector: Matters of design in policy-making and policy implementation. Annual Review of Policy Design, 1(1), 1-11.

- Junginger, S. (2015). Organizational design legacies and service design. The Design Journal, 18(2), 209-226. https://doi.org/10.2752/175630615X14212498964277

- Junginger, S., & Sangiorgi, D. (2009). Service design and organisational change. Bridging the gap between rigour and relevance. In Proceedings of the Congress of International Association of Societies of Design Research (pp. 4339-4348). Seoul, Korea: IASDR.

- Junginger, S., & Sangiorgi, D. (2011). Public policy and public management: Contextualising service design in the public sector. In R. Cooper, S. Junginger, & T. Lockwood (Eds.), The handbook of design management (pp. 480-494). Oxford, England: Berg. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474294126.ch-029

- Kieser, A., & Koch, U. (2008). Bounded rationality and organizational learning based on rule changes. Management Learning, 39(3), 329-347. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507608090880

- King, B., Felin, T., & Whetten, D. (2010). Finding the organization in organization theory: A meta-theory of organizational actors. Organization Science, 21(1), 290-305. http://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0443

- Kurtmollaiev, S., Fjuk, A., Pedersen, P. E., Clatworthy, S., & Kvale, K. (2018). Organizational transformation through service design: The institutional logics perspective. Journal of Service Research, 21(1), 59-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670517738371

- Latour, B. (1986). The powers of association. In J. Law (Ed.), Power, action and belief. London, England: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1984.tb00115.x

- Latour, B. (1987). Science in action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network theory. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Leonard-Barton, D. (1992). Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strategic Management Journal, 13(S1), 111-125. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250131009

- Pahl-Wostl, C., Jeffrey, P., Isendahl, N., & Brugnach, M. (2011). Maturing the new water management paradigm: Progressing from aspiration to practice. Water Resources Management, 25(3), 837-856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-010-9729-2

- Reynolds, M. (2014). Triple-loop learning and conversing with reality. Kybernetes, 43(9/10), 1381-1391. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-07-2014-0158

- Salmi, A., & Mattelmäki, T. (2021). From within and in-between—Co-designing organizational change. CoDesign, 17(1), 101-118. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2019.1581817

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Schön, D. A. (1984). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action (Vol. 5126). New York, NY: Basic books.

- Scott, W. R., Davis, G. F., & Scott, W. R. (2007). Organizations and organizing: Rational, natural, and open system perspectives. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Seravalli, A., Agger Eriksen, M., & Hillgren, P. A. (2017). Co-Design in co-production processes: jointly articulating and appropriating infrastructuring and commoning with civil servants. CoDesign, 13(3), 187-201. http://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355004

- Seravalli, A., Ernits, H., & Upadhyaya, S. (2019). Innovationslabb för avfallsminimering [Innovation lab for waste minimization]. Technical Report. Malmö, Sweden: Malmö University.

- Simon, H. (1991). Bounded rationality and organizational learning. Organizational Science, 2(1), 125-134. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2634943

- Simonsen, J., & Robertson, T. (Eds.). (2012). Routledge international handbook of participatory design. London, England: Routledge.

- SOU. (2013). Att tänka nytt för att göra nytta. Om perspektivskiften i offentlig verksamhet [Fresh thinking to bring benefit. On shifts in perspective in public sector operations]. Stockholm, Sweden: Fritzes.

- SKR. (2021). Forskning och utveckling [Research and development]. Retrieved from https://skr.se/skr/naringslivarbetedigitalisering/forskningochinnovation/innovation/innovationsveckan2021.27258.html

- Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907-39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387-420. http://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

- Star, S. L. (2010). This is not a boundary object: Reflections on the origin of a concept. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 35(5), 601-617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243910377624

- Vink, J., Wetter-Edman, K., & Koskela-Huotari, K. (2021). Designerly approaches for catalyzing change in social systems: A social structures approach. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 7(2), 242-261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2020.12.004

- Wæraas, A., & Nielsen, J. A. (2016). Translation theory ‘translated’: Three perspectives on translation in organizational research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18(3), 236-270. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12092

- Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Weick, K., & Sutcliffe, K. (2007). Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Witmer, H. (2019). Degendering organizational resilience: The oak and willow against the wind. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 34(6), 510-528. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-10-2018-0127

- Zingmark, A. (2016). Innovationsplattformar för hållbara och attraktiva städer. Analys och rekommendationer [Innovation platforms for sustainable and attractive cities. Analysis and reccomendations]. Stockholm, Sweden: Vinnova.