Beyond Good Intentions: Towards a Power Literacy Framework for Service Designers

Maya Goodwill 1,*, Roy Bendor 2, and Mieke van der Bijl-Brouwer 2

1 Power Literacy, Toronto, Canada

2 Delft University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands

Moving into the social and public sector, service design is becoming both more complex and more participatory. This is reflected in the greater diversity and interrelatedness of stakeholders and the wicked problems being addressed. However, although many service designers working in the social and public domains bring into their design practice the intention to make design more participatory and equitable, they may lack an in-depth understanding of power, privilege, and the social structures (norms, roles, rules, assumptions, and beliefs) that uphold structural inequality. In this paper we present findings from seven interviews with service designers to investigate the challenges they face when addressing power issues in design, and their experiences of how power shows up in their design process. By drawing from understandings of power in social theory, as well as the interviewees’ perspectives on how power manifests in design practice, we outline a framework for power literacy in service design. The framework comprises five forms of power found in design practice: privilege, access power, goal power, role power, and rule power. We conclude by suggesting that service design practices that make use of reflexivity to develop power literacy may contribute to more socially just, decolonial, and democratic design practices.

Keywords – Design for the Social and Public Sector, Design Justice, Intersectionality, Reflexivity, Power Literacy, Service Design.

Relevance to Design Practice – As service design moves into the social and public sector with intentions to do good, there is a lack of design scholarship and research addressing issues of power. As such, this paper aims to bridge this gap by developing a shared understanding of, and suggesting a reflexive practice around, power in service design.

Citation: Goodwill, M., Bendor, R., & van der Bijl-Brouwer, M. (2021). Beyond good intentions: Towards a power literacy framework for service designers. International Journal of Design, 15(3), 45-59.

Received Oct. 31, 2020; Accepted Nov. 19, 2021; Published Dec. 31, 2021.

Copyright: © 2021 Goodwill, Bendor, & van der Bijl-Brouwer. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: goodwill.maya@gmail.com

Maya Goodwill (they/she) is a designer, researcher, and facilitator who grew up as a settler on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil Waututh) nations. They have over 10 years of experience working in community engagement, social innovation, city building, and navigating complex relationships and partnerships in the Canadian and Dutch social and public sectors. Maya’s current work focuses on social justice, decolonization, power, and privilege within participatory processes. They hold a MSc in Design from Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands, and have brought their work on power in design as a guest lecturer at Delft University of Technology (Delft, the Netherlands), Emily Carr University (Vancouver, BC, Canada), Carnegie Mellon University (Pittsburgh, PA), and Vancouver Island University (Nanaimo, BC, Canada).

Roy Bendor is Assistant Professor of Critical Design in the Department of Human-Centered Design at Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands. His research explores the relations between design, culture, and politics, and, more recently, the ways in which urban imaginaries and different conceptions of the future influence the design and deployment of smart city technologies. Roy is also a Fellow of the Urban Futures Studio at Utrecht University, the Netherlands, and former editor of the sustainability forum in ACM’s Interactions magazine. His book, Interactive Media for Sustainability (2018), was published as part of the Palgrave Studies in Media and Environmental Communication series.

Mieke van der Bijl-Brouwer is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering at Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands. She has an interest in methods and practice to tackle complex societal challenges and is expert in practices that bridge disciplines including transdisciplinary learning and collaboration, systems thinking, and design framing practices. She applies her research across a variety of societal domains including wellbeing, education, work, and social justice. Mieke travelled different disciplinary domains, starting with a PhD in human-centered design (University of Twente, the Netherlands, cum laude), research and design in public sector innovation, and research and education in trans disciplinarity (both University of Technology Sydney, NSW, Australia). In 2019 she moved back to the Netherlands to work at Delft University of Technology where she co-founded the Systemic Design Lab.

Introduction

Although their intentions are not always made explicit, designers have long been aware of their capacity to do good in and through their work. To boot, echoes of Victor Papanek’s (1972) influential Design for the Real World can be heard in diverse areas of design such as design for public innovation, design for sustainability, social design, and designing for the common good more generally (Bason, 2014; Dorst et al., 2016; Junginger, 2017; Liedtka et al., 2017). The recognition that design has normative implications shapes design outcomes, design practices1, and, more broadly, the culture of design. The rise and evolution of participatory design from its Scandinavian origins (Ehn & Sjögren, 1991) is evidence of this, as is the growth of design for social innovation (Manzini, 2015). Simply stated, given the stakes involved in design, it stands to reason to involve in design projects those whose lives may be impacted as a result.

While service design continues to incorporate more participatory practices (Cottam & Leadbeater, 2004; Holmlid, 2009; McGann et al., 2018; Yang & Sung, 2016), and as it moves more firmly into the social and public sector, good intentions encounter an increasingly complexifying terrain: a growing number of stakeholders with more diverse backgrounds, skills, and expertise; emergent, wicked problems with no clear or immediate solutions; expansive spatial and temporal contexts; more uncertainty, ambiguity, and open-endedness—in short, service design systems include more relations and more exchanges (Julier, 2014). It is in this context that the normativity and value-ladenness of design meet the scale and scope of the issues faced by service designers, and so, to engage with complexity and better represent the perspectives of affected publics, it is imperative that more actors are included throughout the design process. Being a well-intentioned designer, however, is not enough. As Donetto et al. (2015) show, the promise of co-design and participatory design to inherently shift power relations in public service design often remains an ideal that is not reflected in the everyday reality of service design practice. Without a deeper understanding of how the identities of and interrelationships between stakeholders are premised in social structures that uphold structural inequality (such as norms, roles, rules, assumptions, and beliefs), designers risk reproducing existing inequities by keeping power concentrated in the hands of those that are already privileged—be it more influential stakeholders or the designers themselves. As design becomes more diffuse (Manzini, 2015), so should the power of designers.

This is, unfortunately, not always the case. As Bratteteig and Wagner (2014) point out, there is a tension “between the moral stance of participatory design to share power,” and the fact that “designers as experts ... have considerable power” (p. 117). Power dynamics and sharing are made difficult by underlying patterns of domination, hierarchy in relationships, and unequal access to resources, as well as from a lack of respect for differences. As such, it is clear that “design is not something that is neutral or necessarily beneficial for all but has major implications on the distribution of power within the system” (Vink, 2019, p. 108). The playing field, so to speak, is often skewed (Vink et al., 2017).

In response, we argue that as more public and social sector organizations turn to service design to tackle complex social issues, it is becoming critical for service designers to understand how power shows up in their work and the resulting impact this has on the communities they aim to serve. Given service design’s embeddedness in neoliberal capitalist, colonial structures (Ansari, 2017; Irani 2018; Stern & Siegelbaum, 2019), this requires that service design education and practice gain a more nuanced understanding of power dynamics—the complexities, tensions, and pluralities of power that underlie design practices and that may reproduce systemic oppression (e.g., white supremacy, colonialism, cisheteropatriarchy, ableism, etc.) and cause harm to marginalized communities (see Ansari, 2018; Bardzell, 2010; Bratteteig & Wagner, 2014; Costanza-Chock, 2018; 2020; Dombrowski et al., 2016; Holmes-Miller, 2016; Light & Amaka, 2014; Tunstall, 2013; Vink et al., 2017). Good intentions need to be matched by equitable practices.

Power Issues in (Participatory) Design Studies

Concerns about power issues in design go back to the origins of the field of participatory design (PD). When PD emerged in the 1970s in the context of designing information technology in the workplace, it sought to rebalance power and agency among managers and workers (Bannon et al., 2018). Bratteteig and Wagner (2014) describe how, in those early days of PD, dealing with different views and possible conflicts between stakeholders in a PD project was seen as part of the process, but that recently “this insight has been somewhat lost in the assumption that ‘working with users’ almost inevitably would lead designers to do the right thing” (p. 7). Similar criticism was raised by Bannon et al. (2018) who argue that the label participatory design seems to have become synonymous with a more banal form of user-centered design, concentrating on local issues of usability and user satisfaction rather than seeking to “intervene upon situations of conflict through developing more democratic processes” (p. 2). At the same time, such issues of power and politics are becoming increasingly important with participatory design moving from the workplace to the public sphere. As Ehn (2008) argues, in this environment there is a need for a public characterized by heterogeneity and difference to constructively deal with disagreements. Björgvinsson et al. (2012) foreground this role of conflict by developing strategies to develop agonistic public spaces—platforms or infrastructures to constructively deal with disagreement. New ways of dealing with power issues and politics, such as infrastructuring (Björgvinsson et al., 2012), are promising. In this paper, however, we start by taking a step back.

Bratteteig and Wagner (2014) state that “designers have to learn how to use their power and how to share it” (p. 3). Further, to acknowledge and diffuse power dynamics in design practice, some in the service design field have called for increased reflexivity when it comes to power (see Hill et al., 2016; Sangiorgi, 2011; Vink, 2019). We agree that there is certainly a need for that, but in order to effectively decolonize and democratize service design processes such reflexive practices first require a foundational understanding and shared language about power. Accordingly, our aim in this paper is to investigate how service designers experience and deal with power in their practice, and to provide service designers with a framework for developing their power literacy.

This paper complements the work of Bratteteig and Wagner (2016), who performed a detailed analysis of power issues in decision-making in four participatory design projects of IT systems. They argue that sharing power in participatory design is “a complex interplay of mechanisms, in which different resources and multiple dependencies and loyalties come to work together” (p. 438), and show how this is not so much about who has a say in which design decisions, but more about the interdependencies that their choices create, and so “participation in some decisions is more important than others” (p. 462). However, instead of investigating design projects in which we ourselves played an active role, as Bratteteig and Wagner did, we investigated the experiences of different service designer practitioners in dealing with power in their design practices.

As a point of departure for developing a foundational understanding and shared language about power, we first turn to social theory, where questions surrounding the sources, structures, and implications of power have long been debated (see Layder, 2006, for an overview). We will then outline our research method for interviewing service designers and present our findings. Next, in the discussion section we combine our literature review and interview findings to develop a power literacy framework, consisting of five forms of power in service design practice and a set of questions to consider for a more reflexive and equitable design practice. In particular, we highlight the role of privilege which, despite a few recent exceptions (for example Harrington et al., 2019), remains underemphasized in participatory design and service design. Finally, grounded in values of social justice, decolonization, and democracy, we discuss how our framework may be applied in order to further develop power literacy and reflexivity in service design.

A Literature Review of Power in Social Theory

To further conceptualize power in service design we asked ourselves, what can we learn from social theory about power to inform service designers’ practice? To achieve this, we conducted a narrative theoretical literature review (Baker, 2016) on power from social theory. Literature was selected based on expert referrals, as well as by exploring key publications around power. As such, the literature review was judgement based. We began with a broad review of social theory literature around power and privilege, which was then narrowed down based on its applicability to design. Further literature was selected based on its relevance to issues related to power, social justice, feminist theory, and equity in the design domain.

Two Forms of Power

Social theory recognizes that power, “the (in)capacity of actors to mobilize means to achieve ends” (Avelino, 2021, p. 16; emphasis removed), is a complex, elusive, and contentious concept (Lukes, 2005), that it can be viewed as both restrictive and productive (Flyvbjerg, 1998), and that it can be used to explain both stasis and change—although often by privileging the former over the latter (Avelino, 2021). One useful way to understand power holds that power can be grouped into one of two distinctions: power to and power over. Power to refers to an actor’s ability or capacity to make something happen. Dowding (1991) describes power to as “outcome power…. the capacity to bring about or help bring about an outcome” (p. 48). In line with this, Pitkin (1972) writes that “power is a something—anything—which makes or renders somebody able to do, capable of doing something. Power is capacity, potential, ability, or wherewithal” (p. 276). Power over, on the other hand, can be understood simply as getting someone to do what you want them to do, and in this sense it is often coupled to domination (Allen, 2016). Understanding power as power over has been widely associated with Marx’s analysis of ideology (Marx & Engels, 1998), and reflected in Weber’s (1978) definition of power as “the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance” (p. 53). As such, power over can be seen as both potential (that is, a capacity possessed even if not exercised) and relational (that is, always exercised in relation to someone else). In this sense, Castells (2009) notes that power is “the relational capacity that enables a social actor to influence asymmetrically the decisions of other social actor(s)” (p. 10).

Although the effects of power differentials are experienced by individuals, they are not individual phenomena, and thus cannot be separated from the larger social and systemic contexts that support them. As Giddens (2002) argues, power is “generated in and through the reproduction of structures of domination” (p. 160), or as Johnson (2001) adds, “privilege, power, and oppression exist only through social systems and how individuals participate in them” (p. 96). This is captured in Marx’s economic analysis of class and the relations of production (Marx & Engels, 1998), but also in Foucault’s (1980) genealogical analysis of how some forms of knowledge—“a whole set of knowledges that have been disqualified as inadequate to their task or insufficiently elaborated: naive knowledges, located low down on the hierarchy, beneath the required level of cognition or scientificity” (p. 82)—are subjugated in and through “the whole complex of apparatuses, institutions and regulations” (p. 95) that make up society.

In the context of design, we can add, power can be understood as an actor’s ability to influence an outcome (power to), enabled by the asymmetry of their relationship with other social actors (or stakeholders) involved in the design process (power over), and structurally built into the design project itself. It follows that in design, power to and power over are inherently tied: an actor’s ability to have influence in any design practice is affected by asymmetrical social relations. To further explore the idea of asymmetry and its relation to identity and social structures, we next review understandings of power and domination from feminist thought.

Power through an Intersectional Lens

Feminist thinkers have made an important contribution to our understanding of power by their nuanced articulation of the systemic nature of oppression and privilege. The latter describes a social relation where members of one social group gain benefits at the expense of another social group (Johnson, 2001). As popularized by McIntosh (1989), and as made robust by consonant concepts such as the matrix of domination (Collins, 1990) and intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989; 1991), privilege is linked to social, political and cultural forms of power, particularly in the way that social structures reinforce existing concentrations of power and therefore maintain an advantage for certain social groups (Winddance Twine & Gardiner, 2013, pp. 8-10). In this sense, privilege is used to refer to “certain social advantages, benefits, or degrees of prestige and respect that an individual has by virtue of belonging to certain social identity groups” (García, 2018).

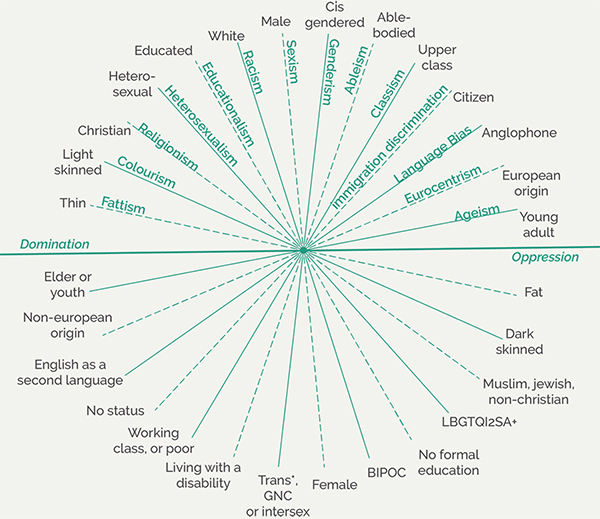

Privileged social groups are those that have historically held positions of dominance, for example, white, cisgendered men. Alongside race and gender, other categories in which privilege unfolds include mental and physical ability, ethnicity, legal status, class, religion, neurodiversity, and education. Importantly, these are not standalone categories. As articulated by black feminist scholars, race and sex, or more specifically the experience of both racism and sexism as endured by black women, are interconnected (Allen, 2016, referring to Gines, 2014). The term intersectionality, at least in its contemporary use, was introduced by Crenshaw as part of a legal framework to demonstrate how what she termed “a single axis framework”, “repeatedly failed to protect Black women workers” (Crenshaw, cited in Costanza-Chock, 2018). The central insight carried by the notion of intersectionality is that forms of oppression are not independent but interrelated (Crenshaw, 1991), but much like the notion of privilege, interrelated forms of oppression are systematized and institutionalized. This is captured by what Collins (1990) calls the matrix of domination. Taken together, intersectionality and the matrix of domination help us understand how systems of privilege and oppression along different axes of identity (e.g., ability, class, gender identity, race, sexuality, and so forth) are interconnected. This view aids the recognition that every social actor is simultaneously a member of multiple social groups, which may afford them both unearned advantages and disadvantages depending on their location. Moreover, the way a social actor perceives a social problem “reflects how the social actor is situated within the power relations of particular historical and social contexts” (Collins, 2017, p. 21), and, due to the distinct location of individuals within intersecting oppressions, they may also have distinctive perspectives on social phenomena. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the matrix of domination.

Figure 1. A visual representation of the matrix of domination: adapted from Morgan (1996).

Shifting our focus to design, we can observe that many paid, expert designers are white, cisgendered, male and/or able-bodied, and that this privileged position can render other situated perspectives and viewpoints invisible (Bunnell, 2019; Khandwala, 2019a; 2019b; Miller, 2017). A privileged view will also likely inform beliefs, assumptions, and norms that shape many of the design decisions being made throughout design projects. If designers become more aware of and sensitive to how privilege and oppression (including their own) function in the contexts in which they are designing, they can make decisions to challenge status quo inequities and patterns of oppression produced in the service or system at hand. Such an awareness may lead designers to create an equitable playing field when it comes to their practice. See for instance the inspiring work by the Design Justice Network (2018), Creative Reaction Lab (2018), the Equity X Design framework created by Hill et al. (2016), and McKercher (2020).

Method

To further investigate service designers’ current awareness of power and privilege and develop a better understanding of the different ways in which power shows up in design in the public and social sector, we conducted seven expert interviews with service designers experienced in social and public sector design projects. Our two main research questions were:

- What challenges do designers face when dealing with power and privilege in their design processes in the public and social sector?

- How does power manifest in social and public sector design practice?

In selecting our interviewees we did not aspire to represent the field as a whole. More modestly, and within the limits of our professional networks, we sought to engage with service designers who were actively working in the social and public sector, enjoy a significant degree of privilege in and through their design work, but at the same time are already aware of their power and privilege. In retrospect we recognize that designers of this profile represent the typical addressees of our research: designers with good intentions and the position to pursue them but without adequate tools to do so. Given the difficulty of access during the covid-19 pandemic, we ended up with seven interviewees, all with considerable experience in the field. Out of these, four were located in the Netherlands and three were located in Canada, all having facilitated or led participatory service design processes in the social and public sector. Three interviewees identify as cismen, and five identity as ciswomen. All are white. A profile of each of the designers interviewed can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of interviewees.

| # | Profile | Location | Years of Experience |

| 1 | Director of a design collective focused on social and public sector issues, lecturer at a design university, and codesign consultant. | Canada | 20 |

| 2 | Vice President at a digital service design agency with a focus on public sector clients. | Canada | 25 |

| 3 | Designer at an innovation and service design company. Experience as a lecturer, coordinator at a design college, as a design researcher at a university, and as the lead designer for a social design agency. | Canada | 15 |

| 4 | Founder of a social design and innovation agency, assistant professor at a design university, and author of a book on design methodology. | the Netherlands | 30 |

| 5 | Associate at a social innovation and participatory research agency, with a focus on designing social labs and participatory processes with municipal clients. | the Netherlands | 10 |

| 6 | Senior associate of social innovation and organizational change at an action research, and design non-profit. | the Netherlands | 30 |

| 7 | Founder and designer at a service design agency focused on public and social sector projects. | the Netherlands | 20 |

The semi-structured interviews were conducted virtually, and lasted for about an hour on average. Questions focused on the designers’ experience and understanding of power in their own practice. We asked them about what power means to them, about when and how they have noticed power imbalances in the projects they facilitated, and how they dealt with those if and when they occurred. This way we sought to avoid abstract or overly theoretical discussions and instead to focus on concrete narratives and events. Although the number of interviewees is relatively small, their responses provided us with very rich insights and a point of departure for considering power in service design in relatively practical terms.

To answer our first research question we employed an inductive thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Each interview was audio recorded and fully transcribed (verbatim). The first author then highlighted and coded relevant sections, and clustered them according to three emerging, overarching themes: challenges related to power; perceived sources of power; and lessons learned by designers. The process was iterative, and to sharpen the themes and increase consistency, all co-authors (which are of different cultural and professional backgrounds) reviewed the clustering outcomes. Nonetheless, we recognize that our coding and clustering process was largely generative (Sanders & Stappers, 2012) instead of relying on coding frequency or on a specific clustering analysis technique (Macia, 2015).

The second research question was addressed through an abductive approach (Dubois & Gadde, 2002), in which insights from the initial coding and clustering process fed into our reading of the literature and vice versa. In this way, our reading of the literature and our interpretation of the interviews informed each other, allowing us, as Dubois and Gadde (2002) write, to pursue “fruitful cross-fertilization where new combinations are developed through a mixture of established theoretical models and new concepts derived from the confrontation with reality” (p. 559). Whereas our initial themes were specific to the interview process (so to a large extent reflected our intentions when asking the questions), the new, emerging themes allowed us to develop the framework that we present in Table 2.

Findings: How Power is Experienced in Service Design

First, we present the findings with regard to the challenges interviewees referred to when addressing power dynamics, followed by a group of themes from the interviews that address the second research question of how power shows up in service design practice.

Which Challenges Do Designers Face When Addressing Power in Their Practice?

The challenges experienced by service designers include becoming aware of power differentials too late, difficulties in moving beyond biases and incorporating less privileged viewpoints, a lack of shared understanding of meaningful participation, and—as a precursor to the previous three challenges—a gap when it comes to acknowledging the impact of power and privilege in design practice and education.

1. Power as an Afterthought

Four interviewees indicated that power dynamics and privilege, if thought of at all, were usually only addressed once a negative effect of the design process had been perceived by or brought to the attention of the design team. Power differentials, in other words, were merely an afterthought. Even though designers wanted to address inequities and make decisions that would empower all stakeholders, it was not something that was clearly identified and incorporated into the design process right from the beginning. Instead, it most often only came up after outcomes had largely been determined, and the rules, norms, and assumptions guiding the project had already been established. As Interviewee 3 indicated, “there are moments of power across the entire design process […] that’s really something designers need to be made aware of from the beginning.” Designers, it follows, had trouble challenging existing power dynamics and social structures because they were only identified and addressed once it became too late or too difficult to make a change. As Interviewee 1 mused, “how can we bring these conversations right up to the front and ask ‘what power and agency do each of you have?,’ rather than just thinking about it quickly and moving on?”

2. Difficulties in Incorporating Alternative Viewpoints

Another challenge that came up during interviews was the need to respond to power differentials, once they were recognized, by including alternative viewpoints and ways of knowing in design projects. Interviewees told us that they valued the perspectives of marginalized and less privileged voices. Even so, they often struggled to meaningfully incorporate those perspectives into their design practices because of systemic reasons—the contexts in which they worked, their clients, and so forth. There also appeared to be unconscious biases when it came to alternatives. Three interviewees suggested that the design field may be unaware and/or unwilling to accept the validity of non-western viewpoints, narratives, and methods (see also Escobar, 2018). In some cases the challenge lies in identifying how current social structures (norms, rules, roles, and beliefs) and ways of designing might exclude or produce inequities for stakeholders with less privilege. For example, Interviewee 1 spoke of a project that served an indigenous population. By working with local leaders and social planners they noticed the inadequacy of their approach and came to realize that having “[elders] share their truths was something design thinking [alone] could never accomplish.”

Related to this, interviewees pointed to the need of the design field as a whole to acknowledge these biases. As Interviewee 7 told us: “I think a lot of designers ... they come with an idea that they take a very low, or let’s say independent or unbiased role in the process. I think we have to accept that that’s not true.” Interviewee 1 spoke about this challenge as a result of the way that, traditionally, designers perceive themselves as helpers or problem-solvers, especially in the social and public sector, due to their so-called expert status. This can result in paternalism or play out as a white savior complex with the communities they aim to serve.

3. Lack of Shared Understanding of Meaningful Participation

Due to the plurality of interpretations of participation, interviewees pointed to a lack of alignment over what it meant to have meaningful participation in design projects. One interviewee described participation—what they referred to as sharing agency—as a spectrum, a sentiment that echoes critical accounts of empowerment-by-participation (see Arnstein, 1969; International Association of Public Participation, 2018), and that was shared by two other interviewees. In the words of Interviewee 3:

There are constraints of time, money and investment that come into play on these types of decisions, and the intention of the organization versus the values of the designer. All these kinds of things come into play in setting the conditions of where on the spectrum can you share this agency, and I think it’s important for designers to be aware of it. I would challenge that designers are not aware that [participation] is one of the considerations in their design process.

Although most interviewees viewed participation as a way to share power and integrate democratic values into their design work, this intention did not always translate into practice. When talking about a recent design project involving their local municipality, Interviewee 5 mentioned that there was a misalignment when it came to what counts as meaningful participation: “I don’t feel like in this specific scenario, that the municipality has done a very good job at distinguishing ‘participation’ from truthful collaboration.” The lack of a shared language about participation and the values associated with it proved challenging.

4. A General Lack of Awareness of the Importance of Power and Privilege in Design Practice and Education

While all seven interviewees were aware that as designers they held a significant amount of power, the majority of interviewees perceived there was a general lack of awareness when it came to addressing power in the field of design. Pointing to an absence of meaningful discussions about power and privilege in much of their design education and practice, five interviewees suggested that the lack of effective language and tools to consider power created a significant void. As Interviewee 1 put it, “it was a major [gap], nothing that ever came up in two design degrees.” As such, we understand this challenge as the precursor to many of the previous challenges discussed above.

How Power Shows Up in Service Design Practice in the Public and Social Sector

The interviews we conducted left no doubt that there is indeed a need to better understand, reflect on, and respond to power dynamics in service design practices. They also provided more insight into how power manifested in service design practice, including the identification of privilege and expertise as sources of power. Additionally, designers explained how power played a role in setting up the design process, in defining participatory processes (including access, roles, and rules), and when converging towards solutions.

1. Privilege as A Source of Power in Service Design

Three interviewees indicated that they had a fair amount of power as a result of their privilege, and that this resulted in various biases, gaps, and obstacles in ensuring that their design practice was equitable. For example, Interviewee 1 shared that a recent mandatory professional development training about equity, diversity, and social inclusion helped to “shine a light on how white our faculty is, how white our resources are.” This in turn has made them realize the biases and gaps they bring with them into their design work due to their own white and cisgender privilege. Similarly, Interviewee 7 mentioned that “how design usually is done isn’t very inclusive [...] there’s a lot of white bias—in the design process, in our cultural views on how people behave, and our assumptions.”

2. Expertise as A Source of Power in Service Design

Interviewees noted that their title or perceived role as an expert designer afforded them power and influence over community members with lived experience of the issue. For example, Interviewee 5 indicated that, even though the municipal client they often work with has a lot of power over decisions, “we have influence because we’re an expert party [in the project], meaning that they have some level of trust in us.” Similarly, Interviewees 1, 2, and 3 also mentioned feeling that one source of their influence was their status as an expert, and how this often meant they had the trust of various actors before even beginning a project. Mentioning a project where they felt like they had considerable power, Interviewee 1 described the client telling them, “we trust you, you’re the expert.” Even though this expert role affords designers power, as Interviewee 5 indicated, “if you’re an expert in the process, it doesn’t mean that you’re also experts in the content of the process. That is kind of a misunderstanding in my opinion.”

3. Power in Setting Up the Design Project

Related to expertise, four interviewees mentioned that they felt they possessed significant power while setting up a project. This includes the power to initiate and frame a design project, which will have a considerable impact on every following decision. Although interviewees expressed the belief that designers may not necessarily have complete power here, since it is the client or funder that usually initiates the project, they nonetheless maintain a significant amount of influence over the framing and structuring of the design process. As further shared by Interviewee 3:

Even when you’re designing the process and thinking about how am I engaging these participants—are you sort of giving someone the assignment and letting them do it, and then checking in and joining up with them, or are you coming in with someone as a subject—even making those decisions there’s an inherent power already happening before you’ve even begun.

4. Power in Defining Participation in the Design Processes: (a) Access, (b) Roles, and (c) Rules

In discussing participation in the design project, interviewees felt that they (as designers) held power as a result of three areas of influence; access, roles, and rules. They spoke of participation as something that did not have one specific meaning, thus giving designers the power to determine the depth of participation in any given step of the design process.

First in terms of access, interviewees discussed the ability to determine who was invited to participate in the design process, how, and at what point. Speaking to this point, Interviewee 3 discussed how, “if you’re not conscious about it, and you know, you’re inviting someone to come to you or you’re going to them to talk to them, inherently there is a dynamic there.” As such, it seems that interviewees had considerable influence in determining who participated and the extent of participation throughout the design project.

An additional aspect in relation to participation is the capacity of designers to define and uphold the roles of other actors. For example, designers decide how to include people who have first-hand experience of the social issue being addressed and name them accordingly—as subjects to collect data from, users to test solutions with, experts from the community to consult with, co-designers of solutions, or some other variation. As interviewee 3 indicated, “I think that it’s a spectrum that goes from not having any agency until the end, to full agency where people are deciding with as little intervention from the designer as possible.”

Lastly, interviewees discussed how, as designers, they were largely able to set the rules when it came to determining the way stakeholders would work together during moments of participation and collaboration, including setting norms around conduct, language and jargon, and defining location and time of sessions. In the words of Interviewee 7, “There’s definitely power involved in being a designer, because you design the process, you help people with questions, you steer them. I won’t say it’s like puppetry, but in a way, you do have that power. And I think it’s very important to realize that.”

5. Power in Converging towards Solutions

Finally, a number of interviewees mentioned that much of their own power stems from having access to the synthesis or convergence stage of the design process, where the data gathered through research activities is interpreted, analyzed, and operationalized. In the words of Interviewee 3, “There are a lot of moments where we make decisions about prioritizing with research, so I think there’s a lot of power in the analysis and synthesis phase.” As indicated, in this stage of a design process needs and insights are often prioritized, and important decisions are made. This power inherent in convergence was summarized by Interviewee 5 as “a kind of entitlement to decide what is important.” Interviewee 1 further added to this sentiment, indicating:

As a designer, we do this workshop and then we bring everything back, and we get to make the decisions about what’s important, right? And so I think there’s still a question—as [design] methodologies are being practiced, how do we keep removing ourselves from doing the synthesis, how do we keep the participants actively involved and engaged?

Theoretical Combining and Discussion

The challenges reported by the interviewees confirm the need to develop a better understanding of what power is and how it manifests in design practice. The fact that it was often addressed too late and that designers often felt inadequate to shift power dynamics demonstrates a gap when it comes to understanding and learning about power on an individual level. At the same time, the lack of a shared understanding about meaningful participation and the lack of awareness about power and privilege in the design field, indicate that there is a need to build a common language around power in design in order to meaningfully confront inequities.

Along with these challenges, the interviews also provided insight into different ways power shows up in design practices, namely through privilege, expertise, setting up, defining participation, and converging. Building on the work of service designer Ross (2019), if we understand a design process as a network, these interview insights can be mapped onto Castells’ (2011) network theory of power. As such, Castells’ theory and Ross’s subsequent work provide us with a useful starting point for building a shared language for understanding power in design. When integrated with insights from our interviewees, they allow us to create new combinations (Dubois & Gadde, 2002) and suggest a framework for developing power literacy for service designers.

A Network Theory of Power

Castells (2009; 2011) suggests that in a societal network the nodes represent social actors, and the ties that connect them are social relations. As such, service design projects can be likened to societal networks in that they include a number of actors (e.g., designers, clients, participants, users), who are connected to each other based on their roles and relationships. According to Castells (2009; 2011), four types of power can be found within a network: 1) networking power; 2) network power; 3) networked power; and 4) network-making power. Networking power can be thought of as the ability to influence who is included and who is excluded from the network itself. Network power can be understood as the power that comes from the standards that are mandated by the network. Networked power can be understood as the power that certain social actors have over other social actors who are included in the network, as determined by an actor’s role and position within the network. Finally, network-making power is the ability to set the goals of the network itself, as well as to determine protocols for governing the way the network will work, including the values and interests it is organized around. Next, we combine this theory with our insights from both the interviews and literature review in order to identify five forms of power in service design practice.

Five Forms of Power in Service Design Practice

Based on our literature review and interviews, as well as Castells’ network theory of power, this section outlines five forms of power that manifest in service design practice. We map our interview insights onto four forms of power derived and developed from Castells’ network theory of power, as well as onto a fifth form based on feminist notions of power (as discussed above). We have named the five forms of power privilege, access power, goal power, role power, and rule power (see Table 2). We discuss them in this order.

Table 2. Five sources of power in service design in relation to literature and interview results.

| Five sources of power in service design practice | Interview themes related to research question 2 | Literature |

| Privilege | Privilege (1) | Systems of privilege; Intersectionality; Matrix of domination (Collins, Crenshaw, McIntosh, Johnson) |

| Access Power | Participation: Access (4a); Converging (5) | Networking power (Castells) Power in participatory decision-making (Brattegeig & Wagner) |

| Goal Power | Setting up the design process (3) | Network-making power (Castells) |

| Role Power | Expertise (2); Participation: Roles (4b) | Networked power (Castells) |

| Rule Power | Participation: Rules (4c) | Network power (Castells) |

Privilege

The first form of power, privilege, is the type of power that allows a stakeholder to influence a design process due to an unearned advantage based on their social position or identity. Three of the interviewees explicitly mentioned they were aware of their privilege, and how it was further amplified by their design expertise. However, when a designer—or any other stakeholder involved in a design project—has privilege, the full extent of their unearned advantage is often invisible to them. Because identity categories do not exist independently from each other and are intersectional (as discussed earlier), it is possible to have privilege while experiencing oppression at the same time. Thus, we argue that it is important for designers to note which social identities, perspectives, and worldviews are being represented in design practices, and understand what impact this may have. For example, because many designers in paid and influential roles continue to be white, cisgendered, male, and/or able-bodied, other perspectives and practices of design that fall outside of the dominant, Anglo-Eurocentric sphere are often erased, marginalized or appropriated (Ansari, 2018; Bunnell, 2019; Khandwala, 2019b). Since privilege will inform the beliefs, assumptions, rules, and norms that dictate many of the design decisions throughout the project, it influences the other four forms of power. In this sense, privilege precedes and suffuses design practice even before a specific project is initiated.

Access Power

Castells (2009) networking power stands for the ability to influence who is included and who is excluded from the network itself. Within the context of service design, we therefore define access power as the ability to influence who is included and who is excluded from a service design project. Our interviews indicated that access power can be understood as both a form of gatekeeping for a design project in general, as well as something that changes within the process at different phases—in particular when converging towards solutions. This is well illustrated in Bratteteig and Wagner’s (2014) detailed account of participation in the development of IT systems, where they note that the decisions made in participatory design processes are better understood as intertwined, mutually-affecting design moves. It is therefore not just about who has a say in decisions, but about the interdependencies their choices create. We can conclude that access power is important because the input, experience, and perspectives that are included in a design project have a considerable impact on the decisions that are made, the relationships between stakeholders, and ultimately on outcomes. If certain stakeholders and certain social groups are excluded, the design process, its outcomes, and the relationships that are built throughout risk reproducing existing inequities and power dynamics.

Goal Power

The third form of power in service design practice is goal power, adapted from Castells’ (2009) network-making power. As reflected in the interviews, goal power refers to the ability of designers to initiate and frame the design project, including the way in which problems are defined, goals are chosen, and the design project as a whole is structured. These decisions carry considerable impact on the design process and its outcomes, and often position designers as agenda-setters. As a result, the entire design project and its outcomes will be quite different and will serve different interests depending on which stakeholders have a share of goal power. In order to avoid reproducing inequities, it is valuable to recognize which stakeholders have influence over framing decisions (and which do not), and how this will impact participation, inclusion, and outcomes.

Role Power

Role power, the fourth form of power in our framework, is adapted from Castells’ (2009) networked power, and relates to the themes of expertise and defining participation from the interviews. It references the ability to influence the roles that different actors—those who have already been given access to the project—will assume during a design project. This includes any roles assigned to actors in the so-called design network (e.g., design expert, participant, interviewee, co-designer, user, etc.), the resulting hierarchies that emerge, as well as the capacity of each actor to influence decision making. In Foucauldian terms, we can see these elements as part of design’s disciplinary normalization (Foucault, 1980). The decisions that designers make in relation to their role power will affect the experience for all stakeholders, for as Manzini (2015) writes, “design tends to express itself from the point of view of the people involved” (p. 93).

Rule Power

The last form of power, adapted from Castells’ (2009) network power, is rule power, understood as the ability to establish the way that actors included in the design network will work together. This often pertains to what designers consider ‘rational’, ‘normal’, or ‘valid’. As Flyvbjerg (1998) argues, “Power determines what counts as knowledge, what kind of interpretation attains authority as the dominant interpretation. Power procures the knowledge which supports its purposes, while it ignores or suppresses that knowledge which does not serve it” (p. 226). In this sense, acknowledging ancestral, artistic, and experiential ways of knowing as equally valid to more ‘rational’ or practical modes (Perry & Duncan, 2017), provides a necessary corrective to the power/knowledge structures that underlie mainstream design practice.

While some rules are made explicit, functioning as formal protocols for participation, others remain hidden, coded, opaque, latent, not fully specified, or become internalized (Foucault, 1984). These rules also establish norms, assumptions, and beliefs which determine how much influence and, as consequence, agency each actor will have, including, for instance, norms around conduct, the language and technical jargon used, and decisions about location, set-up and length of co-design sessions. In this sense, rule power and role power seem to work closely together since rule power may render certain stakeholders as outsiders, deviants, or marginal and thus affect their roles. Recent initiatives therefore challenge common participatory structures of, for example, design workshops to avoid unintentional harming underserved communities (Harrington et al., 2019) and offer asynchronous participation to people for whom the workshop environment is physically, socially, emotionally, linguistically, or cognitively difficult to engage with (Davis et al., 2021). The way that rule power is used will therefore determine how comfortable different actors are with sharing their knowledge, whether certain stakeholders are heard at all, and what ways of knowing and doing are centered.

Interrelatedness of the Five Forms of Power

It should be noted that the five forms of power can be found throughout the entire process of any given design project, although at certain moments some forms of power seem to be more prevalent or active than others. For example, when setting up a project, goal power is particularly relevant and prominent. On the other hand, role power will be more pronounced during moments of divergence in the design process, when different stakeholders may express contrasting views or wishes for the project. While the concept of intersectionality as presented in our literature review draws our attention to the complexity and interdependencies of elements of privilege, and Brattegeig and Wagner’s (2014) work highlights the interdependencies of design decisions in participatory design, the interdependencies of the five forms of power that we propose here further expand our understanding of the complexity of power in design practice.

Reflexivity: Building Power Literacy in Service Design

When it comes to creating a more socially just design practice, the main challenge identified here is the designer’s lack of awareness, sensitivity to, and understanding of how power dynamics and differentials affect stakeholders, the relations between them, and the social issues addressed in and through design. It is difficult for service designers to create social change without recognizing the ways in which they are complicit in upholding the status quo, even if it is unintentional. To fill this gap, designers will first have to recognize the ways in which power and privilege are distributed within design processes. In order to do this, we argue that designers must develop their power literacy.

Traditionally applied to the context of reading and writing, literacy refers to someone’s competency and knowledge of a particular subject. UNESCO (2004) defines literacy as “the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts” (p.13). That said, the notion of literacy has extended beyond the traditional domain of reading and writing to apply to media (Livingstone, 2004), data (Koltay, 2015), futures (Miller & Sandford, 2019), and emotional intelligence (Brackett, 2019).

In the context of power, we interpret literacy as the ability to recognize, name, understand the impact of, and regulate one’s own power position and the power position of the stakeholders around them, as well as to identify the underlying social structures and systems that lead to power differentials. Since reflexivity is the ground from which power literacy grows, the latter requires an ability to be sensitive, self-aware, and understanding of the cause and impact of power structures. Only then would the designer be able to shift power in a way that aligns with such values as equality, inclusion, accessibility, and justice. A designer who has developed power literacy will understand their own position, including the influence that they have, the sources of that influence, and how it will affect the stakeholders they are working with. Moreover, they will be sensitive to power dynamics as soon as they appear in a design project, and will be able to use their skills to identify the impact that this may have on various stakeholders—especially those that are most vulnerable or marginalized.

In their call for transformation design, Burns et al. (2006) argue that service design must acknowledge that “design is never done”: “because organisations now operate in an environment of constant change, the challenge is not how to design a response to a current issue, but how to design a means of continually responding, adapting and innovating” (p. 21). Given the considerable responsibilities involved in transformative practice, Sangiorgi (2011) calls for service designers to introduce reflexivity into their work to address issues of power during each designerly encounter, and for service design scholars to deepen the meaning and practice of reflexivity. We agree with Sangiorgi that reflexivity and positionality, common concepts in social theory, could be better integrated into (service) design education and practice. In the context of research, reflexivity refers to “the examination of one’s own beliefs, judgments and practices during the research process and how these may have influenced the research” (Hammond & Wellington, 2013). In feminist Science and Technology Studies (STS), reflexivity is often addressed alongside the notion of situated knowledge, according to which the scientific status of objectivity is rejected due to the recognition that a researcher’s (or a scientist’s) personal identity and lived experience cannot be excised from their process of knowledge production (Haraway, 1988). While the researcher’s position may be influenced by their “personal values, views, and location in time and space” (Sánchez , 2010), it may also reflect more structural aspects such as “the stance or positioning of the researcher in relation to the social and political context of the study—the community, the organization or the participant group” (Coghlan & Brydon-Miller, 2014). The lesson for designers is clear: they should employ empathetic engagement, be aware of, and explicit about their own position vis-a-vis the context of the project, and avoid the belief that “the designer, as creative visionary, is somehow suspended above the fray of bias, blind spots, and political pressure” (Iskander, 2018). Barring that, a lack of reflexivity in design practice and a limited awareness of positionality will promote a false notion that design and designers are objective or value-free. Inversely, a greater awareness of the social structures influencing design can help designers to intentionally reshape these social structures in a way that distributes power more equitably within service design practice, and possibly beyond (Vink, 2019).

What we are suggesting, then, is that designers can build power literacy by developing and practicing reflexivity in their work. To enable this, we provide a number of questions meant to spark the designer’s reflexive engagement with power. In Table 3, we outline a power literacy framework that includes the five forms of power discussed above, and corresponding questions for reflexivity.

Table 3. The power literacy framework.

| Five Forms of Power in Design Practice | Reflexivity Questions for Power Literacy |

| 1. Privilege |

|

| 2. Access power |

|

| 3. Goal power |

|

| 4. Role power |

|

| 5. Rule power |

|

Concluding Remarks

The social practices that are part of service design are increasingly recognized as complex and dynamic. This is reflected in the way transformation design introduced a long-term orientation and engagement with a specific service domain and its stakeholders (Burns et al., 2006); in the way perspectives on the object of service design increasingly move beyond service staff-consumer interfaces to include broader groups, teams, and networks involved in co-production of services (Carvalho & Goodyear, 2017); and in the way more distributed and diffuse forms of designing introduce an expanded view on who is designing (Manzini, 2015; Sangiorgi & Junginger, 2015). This complexity increases the urgency to reflect on power dynamics in service design.

In this paper we have argued, in line with calls and movements for design justice (Costanza-Chock, 2020), equity in design (Hill et al., 2016) and decolonizing design (Ansari, 2018; Khandwala, 2019A; Tunstall, 2013), that we need to turn our attention to how systemic notions of power play out in design practice, in order to prevent the reproduction of inequity and injustice by design. Recent calls to address systemic oppression and inequity in the US in the wake of the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement globally, make it clear that designers can no longer ignore the power differentials extended and recreated through their work.

While addressing power differentials has been inherently part of the ideology of participatory design since its establishment fifty years ago, it is currently resurging in response to increased recognition of the need for design justice and, as a result, is leading to numerous promising strategies and proposals to reshape power dynamics in design (see, for example, Björgvinsson et al., 2012; Ehn, 2008; McKercher, 2020; Vink et al., 2017). This paper complements these studies by investigating the experiences of service design practitioners in relation to power. Our preliminary results show the individual challenges of service designers in terms of recognizing power issues and responding to power differentials, as well as challenges related to a shared understanding of power, privilege, and notions of participation. In response to these challenges we argued that if we are to move towards a more socially just service design practice, design practitioners first need to have a better understanding of power, most notably their own. To address this, we combined insights from social theory with the perspectives of designers to illustrate how power manifests in service design practice. We used these to create a power literacy framework that consists of five forms of power, and suggested the adoption of a reflexive practice to put the framework into action. We have also argued that power literacy is necessary for service designers in order to prevent the reproduction of inequities. While this paper offers a theoretical contribution in terms of presenting a complementary perspective on how power shows up in service design in the public and social sector, its key contribution is the way it promises to advance design practice. Still needed are more elaborate and detailed studies to further develop our theoretical understanding of power in service design practice, including ethnographic studies of participatory processes in service design in the public and social sector, as well as investigations of the experiences of participants in such processes in terms of power and privilege.

We are currently evaluating and evolving the framework with service design practitioners working in social and public innovation. We have developed the framework and tested it in the form of a field guide that aims to support a power reflexive practice for individual service designers and design teams, while also provoking reflection and discussion on power and systemic oppression. Expanding upon the framework outlined in this paper, the field guide introduces the idea of power checks—“moments throughout a design project where the design team is asked to reflect on how power is showing up in design decisions and its potential impact” (Goodwill, 2020, p. 39). The field guide outlines a number of critical moments in which power checks should be conducted, including the specific forms of power to pay attention to at those moments. As such, future studies may explore this practice and its impact, and include specific case studies, ethnographies, or other examples.

In addition, future research may focus on how service designers can employ power literacy to move from reflexivity—awareness and reflection of internalized power dynamics and social structures—towards (re)shaping the very power differentials they identify. In doing so, the service design field can take the next step in challenging inequity and power imbalances in public and social sector services, and align impact with intentions to do good.

Endnotes

- 1. Building on Herbert Simon’s (1996) definition, we understand design practices as the patterns of activities involved in generating novel ways to change existing situations into preferred ones. The activities that designers engage in can be considered a broad and complex repertoire of design practices where some practices are universal and others are exclusive to design (Dorst, 2011).

- 2. See more at www.power-literacy.com.

References

- Allen, A. (2016). Feminist perspectives on power. Retrieved from: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2016/entries/feminist-power/

- Ansari, A. (2017). The work of design in the age of cultural simulation, or, decoloniality as empty signifier in design. Retrieved from https://aansari86.medium.com/the-symbolic-is-just-a-symptom-of-the-real-or-decoloniality-as-empty-signifier-in-design-60ba646d89e9

- Ansari, A. (2018, April 12). What a decolonisation of design involves: Two programmes for emancipation. Design and Culture, 10(1). Retrieved from https://www.decolonisingdesign.com/actions-and-interventions/publications/2018/what-a-decolonisation-of-design-involves-by-ahmed-ansari/

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216-224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Avelino, F. (2021). Theories of power and social change. Power contestations and their implications for research on social change and innovation. Journal of Political Power, 14(3), 425-448. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2021.1875307

- Baker, J. D. (2016). The purpose, process and methods of writing a literature review. AORN Journal, 103(3), 265-269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2016.01.016

- Bannon, L., Bardzell, J., & Bødker, S. (2018). Introduction: Reimagining participatory design–emerging voices. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 25(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1145/3177794

- Bardzell, S. (2010). Feminist HCI: Taking stock and outlining an agenda for design. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1301-1310). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753521

- Bason, C. (2014). Design for policy. Surrey, England: Gower Publishing.

- Björgvinsson, E., Ehn, P., & Hillgren, P.-A. (2012). Design things and design thinking: Contemporary participatory design challenges. Design Issues, 28(3), 101-116. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00165

- Brackett, M, A. (2019). Permission to feel: Unlocking the power of emotions to help our kids, ourselves and our society thrive. New York, NY: Caledon Books.

- Bratteteig, T., & Wagner, I. (2014). Disentangling participation: Power and decision-making in participatory design. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- Bratteteig, T., & Wagner, I. (2016). Unpacking the notion of participation in participatory design. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 25, 425-475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-016-9259-4

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. http://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bunnell, I. (2019). The design industry lacks diversity. Retrieved from https://medium.com/wearesnook/the-design-industry-lacks-diversity-37433db48eec

- Burns, C., Cottam, H., Vanstone, C., & Winhall, J. (2006). Red paper 02: Transformation design. London, England: Design Council.

- Carvalho, L., & Goodyear, P. (2017). Design, learning networks and social innovation. Design Studies, 55, 27-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2017.09.003

- Castells, M. (2009). Communication power. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Castells, M. (2011). A network theory of power. International Journal of Communication, 5, 773-787.

- Coghlan, D., & Brydon-Miller, M. (2014). The Sage encyclopedia of action research. London, England: Sage. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446294406

- Collins, P. H. (1990). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. London, England: Routledge.

- Collins, P. H. (2017). The difference that power makes: Intersectionality and participatory democracy. Investigaciones Feministas, 8(1), 19-39. https://doi.org/10.5209/INFE.54888

- Costanza-Chock, S. (2018). Design justice: Towards an intersectional feminist framework for design theory and practice. In Proceedings of the Conference of Design Research Society. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2018.679

- Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. Cambridge, MA: MIT. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12255.001.0001

- Cottam, H., & Leadbeater, C. (2004). Red paper 01 health: Co-creating services. London, England: Design Council.

- Creative Reaction Lab (2018). Field Guide: Equity-centered community design. St Louis, MO: Creative Reaction Lab.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. In K. T. Barlett & R. Kennedy (Eds.), Feminist legal theory. London, England: Routledge.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Davis, A., Niki, W., Langley, J., & Ian, G. (2021). Low-contact co-design: Considering more flexible spatiotemporal models for the co-design workshop. Strategic Design Research Journal, 14(1), 124-137. https://doi.org/10.4013/sdrj.2021.141.11

- Design Justice Network. (2018). Design justice network principles. Retrieved May 14, 2020, from https://designjustice.org/read-the-principles

- Dombrowski, L., Harmon, E., & Fox, S. (2016). Social justice-oriented interaction design. In Proceedings of the Conference on Designing Interactive Systems (pp. 656-671). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2901790.2901861

- Donetto, S., Pierri, P., Tsianakas, V., & Robert, G. (2015). Experience-based co-design and healthcare improvement: Realizing participatory design in the public sector. The Design Journal, 18(2), 227-248. https://doi.org/10.2752/175630615X14212498964312

- Dorst, K. (2011). The core of ‘design thinking’ and its application. Design Studies, 32(6), 521-532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.006

- Dorst, K., Kaldor, L., Klippan, L., & Watson, R. (2016). Designing for the common good. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: BIS.

- Dowding, K. M. (1991). Rational choice and political power. Bristol, England: Bristol University Press.

- Dubois, A., & Gadde, L. (2002). Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. Journal of Business Research, 55(7), 553-560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8

- Ehn, P., & Sjögren, D. (1991). From system descriptions to scripts for action. In J. Greenbaum & M. Kyng (Eds.), Design at work: Cooperative design of computer systems (pp. 241-268). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Ehn, P. (2008). Participation in design things. In Proceedings of the 10th Conference on Participatory Design (pp. 92-101). New York, NY: ACM.

- Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds. London, England: Duke University Press.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (1998). Rationality and power: Democracy in practice. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977 (C. Gordon, Trans.). New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. (1984). Panopticism. In P. Rabinow (Ed.), The Foucault reader (pp. 206-213). New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

- García, J. D. (2018). Privilege (social inequality). Amenia, NY: Salem Press Encyclopedia.

- Giddens, A. (2002). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Gines, K. (2014). Race women, race men and early expressions of proto-intersectionality, 1830s-1930s. In M. M. O’Donovan, N. Goswami, & L. Yount (Eds.), Why race and gender still matter (pp. 13-26). London, England: Routledge.

- Goodwill, M. (2020, July 31). A social designer’s field guide to power literacy. Kennisland. Retrieved from https://www.kl.nl/en/publications/a-social-designers-field-guide-to-power-literacy/

- Hammond, M., & Wellington, J. (2013). Research methods: The key concepts. London, England: Routledge.

- Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

- Harrington, C. N., Erete, S., & Piper, A. M. (2019). Deconstructing community-based collaborative design: Towards more equitable participatory design engagements. In Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), Article No. 216. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359318

- Hill, C., Molitor, M., & Oritz, C. (2016). Equity design: A Practice for Transformation. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e84f10a4ce9cb4742f5e0d5/t/5ec3fe2bbcfabb28349ba9af/1589902892717/equityXdesign+11.14.16.pdf

- Holmes-Miller, C. D. (2016). Black designers: Still missing in action? Retrieved from https://letterformarchive.org/uploads/Miller_Black_Designers_Still_Missing_in_Action.pdf

- Holmlid, S. (2009). Participative, co-operative, emancipatory: From participatory design to service design. In Proceedings of the 1st Nordic Conference on Service Design and Service Innovation (pp. 105-118). Retrieved from https://ep.liu.se/ecp/059/009/ecp09059009.pdf

- International Association of Public Participation. (2018). IAP2 spectrum of public participation. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/Spectrum_8.5x11_Print.pdf

- Irani, L. (2018). “Design thinking”: Defending silicon valley at the apex of global labor hierarchies. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 4(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v4i1.29638

- Iskander, N. (2018, September). Design thinking is fundamentally conservative and preserves the status quo. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2018/09/design-thinking-is-fundamentally-conservative-and-preserves-the-status-quo

- Johnson, A. G. (2001). Privilege, power, and difference. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Julier, G. (2014). The culture of design (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Junginger, S. (2017). Transforming public services by design. London, England: Routledge.

- Khandwala, A. (2019a). What does it mean to decolonize design? AIGA eye on design. Retrieved from https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/what-does-it-mean-to-decolonize-design/

- Khandwala, A. (2019b). Why role models matter: Celebrating women of color in design. AIGA eye on design. Retrieved from https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/why-role-models-matter-celebrating-women-of-color-in-design/

- Koltay, T. (2015). Data literacy: In search of a name and identity. Journal of Documentation, 71(2), 401-415. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-02-2014-0026

- Layder, D. (2006). Understanding social theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Liedtka, J., Salzman, R., & Azer, D. (2017). Design thinking for the greater good–Innovation in the social sector. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. http://doi.org/10.7312/lied17952

- Light, A., & Akama, Y. (2014). Structuring future social relations: The politics of care in participatory practice. In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference (pp. 151-160). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2661435.2661438

- Livingstone, S. (2004). What is media literacy? Intermedia, 32(3), 18-20.

- Lukes, S. (2005). Power: A radical view (2nd ed.). London, England: Macmillan.

- Macia, L. (2015). Using clustering as a tool: Mixed methods in qualitative data analysis. Qualitative Report, 20(7), 1083-1094.

- Manzini, E. (2015). Design, when everybody designs: An introduction to design for social innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT. http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9873.003.0003

- Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1998). The German ideology, including theses on Feuerbach. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books.

- McGann, M., Blomkamp, E., & Lewis, J. M. (2018). The rise of public sector innovation labs: Experiments in design thinking for policy. Policy Sciences, 51, 249-267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9315-7

- McIntosh, P. (1989). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. Peace and freedom, July/August, 10-12.

- McKercher, K. A. (2020). Beyond sticky notes: Co-design for real: Mindsets, methods and movements. New South Wales, Australia: Inscope Books.

- Miller, M. (2017). Survey: Design is 73% white. Fast company. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/3067659/survey-design-is-73-white

- Miller, R., & Sandford, R. (2019). Futures literacy: The capacity to diversify conscious human anticipation. In R. Poli (Ed.), Handbook of anticipation (pp. 73-91). Berlin, Germany: Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91554-8_77

- Morgan, K. P. (1996). Describing the emperor’s new clothes: Three myths of education (in)equality. In A. Diller, B. Houston, K. P. Morgan, & M. Ayim (Eds.), The gender question in education: Theory, pedagogy and politics (pp. 105-123). London, England: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429496530-11

- Papanek, V. J. (1972). Design for the real world: Human ecology and social change. Buffalo, NY: Pantheon Books.

- Perry, E. S., & Duncan, A. C. (2017). Multiple ways of knowing: Expanding how we know. Non-profit quarterly. Retrieved from https://nonprofitquarterly.org/multiple-ways-knowing-expanding-know/

- Pitkin, H. F. (1972). Wittgenstein and justice: On the significance of Ludwig Wittgenstein for social and political thought. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Ross, G. (2019, October 10). Power and service design: Making sense of service design’s politics and influence. Paper presented at the Conference on Service Design, Kölle, Germany.

- Sánchez, L. (2010). Positionality. In B. Warf (Ed.), Encyclopedia of geography. Retrieved from https://sk.sagepub.com/reference/geography/n913.xml

- Sanders, E. B. N., & Stappers, P. J. (2012). Convivial toolbox: Generative research for the front end of design. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: BIS.

- Sangiorgi, D. (2011). Transformative services and transformation design. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 29-40.

- Sangiorgi, D., & Junginger, S. (2015). Emerging issues in service design. The Design Journal, 18(2), 165-170. https://doi.org/10.2752/175630615X14212498964150

- Simon, H. A. (1996). The sciences of the artificial (3rd ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Stern, A., & Siegelbaum, S. (2019). Special issue: Design and neoliberalism. Design and Culture, 11(3), 265-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2019.1667188