Positive User Experience over Product Usage Life Cycle and the Influence of Demographic Factors

JungKyoon Yoon 1, Chajoong Kim 2,*, and Raesung Kang 3

1 Department of Design and Environmental Analysis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

2 Department of Design, UNIST, Ulsan, South Korea

3 I.M.LAB, Seoul, South Korea

This paper reveals how the patterns of positive user experience in relation to a product vary over the usage life cycle, from before purchase to disposal/repurchase, and in what way the positive experience interacts with demographic factors. As constructs of positive user experience, five attributes of positive user experience were adopted in the study: aesthetics; instrumentality; association; self-focused identification; and relationship-focused identification. Love letter, UX curve and retrospective interviews were used as methods. A total of 49 people participated in the study. The results indicate that the critical attributes of positive user experiences differed to a large extent according to the phase of product usage. However, these differences were not significant in terms of gender and age. Among the five attributes, instrumentality played a main role in positive experiences throughout the product usage life cycle, while the importance of the other attributes tended to decrease after first-time usage. The findings highlight implications for design practice that can aid the process of designing for long-lasting positive user experience throughout the product usage life cycle.

Keywords – Experience Design, User Experience, Time, Usage Life Cycle, Demographic Factor.

Relevance to design practice – The paper provides designers with a systematic understanding of positive user experience through the lenses of the phases of the product usage life cycle and influence of demographic factors. The findings can serve as a source of inspiration and reference in holistically addressing intended users’ needs and expectations in different phases of product use.

Citation: Yoon, J., Kim, C., & Kang, R. (2020). Positive user experience over product usage life cycle and the influence of demographic factors. International Journal of Design, 14(2), 85-102.

Received April 24, 2019; Accepted July 14, 2020; Published August 31, 2020.

Copyright: © 2020 Yoon, Kim, & Kang. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: cjkim@unist.ac.kr

JungKyoon Yoon is an assistant professor in the Department of Design + Environmental Analysis at Cornell University. His research focuses on experience design with an emphasis on affective experiences, subjective well-being, and design-mediated behaviour change.

Chajoong Kim is an associate professor in the Department of Design and the founder of Emotion Lab at UNIST. He earned an MSc and PhD at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering, Delft University of Technology. His main research interests range from user experience design, design for well-being and cultural influence in the human-product interaction. With these research topics, he has published in, among others, Design Studies, The Design Journal, Journal of Design Research, and International Journal of Design.

Raesung Kang is a UX designer at I.M.LAB, a Seoul-based interactive media studio developing products and services for healthcare such as first aid and medical training. He earned an MSc in industrial design from UNIST on user experience archiving application development for design practitioners. His research interest is in developing design methodology and tools for promoting empathy between designers and users for better user experiences in products or services.

Introduction

Amassing reliable and detailed data about intended users has become increasingly critical to design practitioners as consumer markets increasingly ask for the development of products and services that ensures personal fit, both physical and psychological (Kramer et al., 2000; Spinuzzi, 2005). One challenge is that many user research approaches tend to focus on identifying users’ needs at hand while being limited in drawing a holistic picture of how their experiences in relation to the products are influenced by and associated with different user characteristics (e.g., prior knowledge, physical capability, and personal values). To overcome the challenge, recently the relationship between user experience and user characteristics has been explored in design research. For example, Kim and Christiaans (2012) and Kim (2014) developed an empirical framework through a cross-cultural study that explained the influence of user characteristics and product types on users’ negative experiences. For instance, complaints related to tactual qualities (e.g., the roughness and friction of materials) are more evident for South Koreans than American and Dutch people when they use a simple product such as an alarm clock. These frameworks are of value in foreseeing and reducing unwanted negative experiences, as they provide a structured overview of when and how users with particular characteristics would be hindered. While useful in avoiding or mitigating negative experiences, in our view they would not be particularly helpful for designers in their endeavour to facilitate positive experiences; minimising negative experiences, that is, the absence of a problem or pain is not necessarily equal to addressing what makes the experience positive (Hassenzahl, 2010).

Therefore, this paper aims to extend the current understanding of the influence of user characteristics on user experience by shedding light on people’s positive experiences with products. In recent years, several initiatives to design for positive experiences have gained attention and momentum in design research and human-computer interaction (HCI). Examples of such initiatives are positive design (Desmet & Pohlmeyer, 2013), experience design (Hassenzahl, 2010), positive computing (Calvo & Peters, 2014) and positive technologies (Riva et al., 2012; for an overview of the initiatives, see Peters et al., 2018; Zeiner et al., 2018). The aforementioned initiatives support designers in being aware of the key factors that contribute to positive experiences (e.g., pleasure, virtue, personal significance, autonomy, competence and relatedness).

Moreover, a number of recent studies address the importance of longitudinal evaluation because user satisfaction with product is ascribed to a wide range of product aspects over time, e.g., aesthetics, physical comfort, usability, social acceptability, etc. The focus of design has extended from addressing the moments of purchase and initial use to establishing a meaningful user-product relationship and its long-term experiential impact. Corresponding to the broadened design focus, researchers have emphasised the necessity of understanding users’ experiences over a long span of time. Hassenzahl and Tractinsky (2006), for example, demonstrated experiential aspects of design, emphasising its dynamic, complex, situated, temporal as well as durable characteristics. Von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff and his colleagues (2006) revealed how pragmatic and hedonic qualities interplay in different phases of product use. According to them, the perceived importance of a product’s pragmatic qualities remains high over time, whereas the appreciation of hedonic qualities tends to taper off.

Karapanos (2013) conducted two studies that provided empirical findings on the differences between initial and prolonged experiences. The first study revealed that in initial interactions with a product, users tend to focus on its usability and the stimulation caused by its aesthetic qualities. After the product has been used for some time, users become less concerned about its usability and other aspects of the product (e.g., novel functionality and communication of a favourable identity to others) become more important. In the second study, three phases were identified in the adoption of the product (i.e., orientation, incorporation, and identification), reflecting different qualities of the product with distinct temporal patterns. The phase of orientation begins after anticipating an experience and results in the formation of expectations. The transition happens across the three phases motivated by three forces: familiarity; functional dependency; and emotional attachment. Before orientation, expectations are formed based on anticipation. In the orientation phase, the experience of novel features and learnability leads to excitement or frustration. In the phase of incorporation, long-term usability becomes even more important than the initial learnability and the product’s usefulness becomes the major factor impacting users’ overall judgements. Finally, personal and social meaning play an important role in the identification phase once the product is accepted.

These studies offer insights into how users’ experiences generally change over time. However, it is of importance to note that few empirical studies have investigated how and when particular attributes of positive experiences arise over the product usage life cycle and how they would differ depending on user characteristics. This is critical in that the degree of users’ perceptions of the experiences (both positive and negative) fluctuates over the phases of the usage life cycle—from before purchase to usage to disposal/repurchase (Karapanos et al., 2010)—and different user populations may show different patterns. We propose that having an awareness of these differences can be advantageous for designers in gaining an in-depth understanding of their intended users and deliberately creating positive experiences that fit their characteristics (e.g., demographic factors).

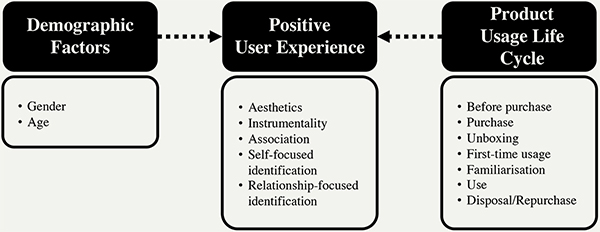

The paper explores possible links among user characteristics, product usage life cycle and positive user experience.1 The research question was: how do interactions between demographic factors and usage life cycle affect positive user experience? To answer the research question, an exploratory study was carried out. The study examined: (1) how the product usage life cycle interacts with positive user experience; and (2) how demographic factors affect positive user experience (see Figure 1). In the following section, we look at the literature on designing for positive user experience, the various roles of demographics in user experience and the attributes of user experience, based on which the study was operationalised. Then, we report the study set-up and its results. The paper finishes with a discussion of the key findings and their implications.

Figure 1. The conceptual framework of the study.

Designing for Positive User Experience

In recent years, there has been an emerging interest in the relevance and applicability of design in facilitating positive experiences that build on the insights from the scientific studies of well-being and happiness (i.e., positive psychology). This section offers a brief overview of the development of initiatives in the fields of design and HCI research, and the implications for the current paper, before it introduces and reports the main study.

Recognising the potential contribution of design and technology to well-being (both psychological and physical), researchers have explored the idea of how products can be developed to support users in their pursuit of a pleasurable, purposeful and satisfying life. The approaches, in general, extend beyond the traditional focus of troubleshooting, that is, minimising discomfort and inefficiency caused by design. Instead, they aim at designing products that explicitly address factors associated with well-being, such as pleasure and relatedness. For example, positive computing (Calvo & Peters, 2014) focuses on developing technologies that enable determinants of well-being (e.g., gratitude, self-awareness and autonomy) and argues for the necessity of evaluating the design outcomes against such determinants. Similarly, positive design (Desmet & Pohlmeyer, 2013) builds on insights from positive psychology to create products that mediate or enable experiences that are pleasurable, meaningful and virtuous. The framework of positive design indicates that design-mediated well-being requires at least one of these three aspects without any of them conflicting with the others. Experience design (Hassenzahl, 2010) focuses on fulfilling universal psychological needs as a means of increasing possible user happiness. Hassenzahl proposed to identify patterns of need-fulfilling experiences and inscribe them into products or activities enabled by the products. More recently, by incorporating social practice theory, Shove et al. (2012) and Klapperich et al. (2018) developed positive practice canvas (PPC), a design tool that helps designers systematically gather nuanced insights about everyday positive experiences and design for them. PPC supports designing for well-being by guiding the process of gathering instances of enjoyable and meaningful practices and identifying related psychological needs.

Although the terms look different across approaches, the focus is commonly on the short- and long-term impact of design on users’ well-being by leveraging well-being-related determinants for the conceptualisation and evaluation of products. We adopt the meaning of positive experience suggested by the framework of positive design (Desmet & Pohlmeyer, 2013) because it accounts holistically for the constructs for positive experience in human–product interactions: positive affect (i.e., pleasure), pursuit of personal goals (i.e., meaning), and moral good (i.e., virtue) experienced through products. Thus, in the present research, experiences are regarded as positive if they satisfy at least one of the following criteria without conflict: (1) the experiences involve pleasant feelings; (2) the experiences are in line with personal values and goals; and (3) the experiences involve or result in morally good behaviours for oneself or others.

The aforementioned approaches provide inspiring pathways towards designing for positive experiences by extending the issues of design from the narrow emphasis on physical fit and efficiency to broader psychological human needs. However, as pointed out by Peters et al. (2018) and Klapperich et al. (2018), these theory-driven approaches can be difficult for designers to apply to their practices because they mainly deal with broad directions, being limited in offering clear design features relating to well-being determinants. The broad view may not be actionable enough for designers in addressing specific contexts or user groups.

To overcome these challenges, recent studies have explored how positive experiences could be designed for in specific contexts. Examples include an in-depth analysis of need fulfilment in leisure and work contexts by Tuch et al. (2016), while Lu and Roto (2016) explored positive experience (particularly pride) in the domain of work. These studies enable designers to take a close look at the ways in which design contributes to positive experiences. While helpful, the focus of these studies tended to be on a particular context in isolation, so were limited in providing a comprehensive overview of when and how people find their experiences positive in relation to products across different contexts and users’ characteristics (e.g., gender and age). Therefore, the current study aims to investigate the roles that products play in positive experiences in everyday situations, paying attention to the influence of user characteristics from a long-term perspective, i.e., product usage life cycle.

Identifying the Influence of Demographic Factors on Positive Experiences over Product Usage Life Cycles

The previous section explained the concept of positive experience in relation to the literature on design for well-being. This section reports on a study that investigated how positive user experience varies over the product usage life cycle and what roles demographic factors play. Before reporting the study, we describe how it was operationalised with a focus on user characteristics, attributes of user experience and product usage life cycle.

Roles of Demographic Factors in User Experience

Users can be described in many ways: demographic factors; medical conditions, personality; socio-economic circumstances; technology literacy; anthropometry; and physical and cognitive capabilities. The importance of considering users’ individual differences (i.e., user characteristics) has gained attention in design research with an emerging realisation that, apart from a product’s functions and performance, the perceived qualities of user experience can be ascribed to variations of user characteristics. Several factors of user characteristics have been studied in terms of their influence on consumers’ complaining behaviour (Donoghue & Klerk, 2006; Keng & Liu, 1997), consumer (dis)satisfaction (Chen-Yu & Seock, 2002; Kim, et al., 1999; Mooradian & Olver, 1997; Sheth, 1977) and usability issues (Han et al., 2001). Recently, Kim (2014) and Kim and Christiaans (2016) identified that user personality and socio-economic aspects have no correlation with usability problems with consumer electronics. The study, however, revealed a strong correlation with age differences. For instance, younger people mainly complained about the functional quality of their product (e.g., performance), while older people largely complained about the operation of a product (e.g., hard to use). Interestingly, gender made no difference in the occurrence of negative user experience according to the results of the study. While the influences of several types of user characteristics on negative experiences have been extensively studied, whether and how the findings could be replicated in relation to positive experiences are yet to be explored. In this paper, we focus on demographic factors, in particular gender and age. While all other factors of user characteristics have some relevance to design, these two factors were specifically chosen because they have been proven to be related to general consumer preferences and satisfaction with product use (for an overview of the relevance of user characteristics to design, see Leventhal et al., 1996).

Attributes of User Experience

For the current study, five attributes of user experience (hereafter, UX attributes) were determined2: (1) aesthetics; (2) instrumentality; (3) association; (4) self-focused identification; and (5) relationship-focused identification. These were based on the frameworks of user experience (e.g., Hassenzahl, 2003; ISO, 2010; Rafaeli & Vilnai-Yavetz, 2004), product experience (e.g., Desmet & Hekkert, 2007) and product pleasure (e.g., Jordan, 1999; Norman, 2004). In a previous study (Kang et al., 2016), the representativeness and inclusiveness of the five attributes were validated through an online survey in which 102 participants described their past positive experiences in response to products. All of the collected sample experiences could be effectively represented by the five attributes. Table 1 outlines the definitions and examples of the attributes.

Table 1. The definition and example quote of five UX attributes.

| Attribute | Definition | Example quote |

| Aesthetics | The experience is about the perceived material qualities of a product, including visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, and gustatory senses. | “I love my Lamy Safari because of the shape and texture of the fountain pen.” |

| Instrumentality | The experience is about how useful and efficient a product is in achieving task-oriented goals. Instrumentality is closely associated with usability, convenience, functionality, and practicality. |

“My AeroPress machine is easy to make brewed coffee and functionally simple.” |

| Association | The experience is attributed to something (or someone) that is represented by the product. A product plays a mediating role that stimulates interpretation, memory retrieval, and association (e.g., a sense of achievement portrayed by a trophy). | “I cherish this necktie that I received from my daughter because it represents her love for me.” |

| Self-focused identification | The experience is about the influence of using (or owning) a product on one’s self-perception and expression of their identity (e.g., being an independent traveller enabled by using a navigation app). | “I like my Nike running shoes because they express my lifestyle–young, energetic, explorative, and healthy.” |

| Relationship-focused identification | The experience is about the influence of using (or owning) a product on one’s social identity and relationships with other people (e.g., showing one’s appreciation by sending kudos to team members through a chatting-app). | “I gladly followed the dress code policy to show my respect to the golf club’s members and its tradition.” |

Product Usage Life Cycle

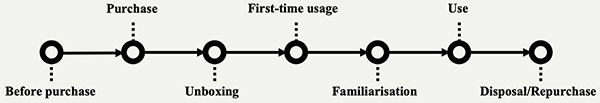

To identify when and how demographic factors influence positive user experience in different phases of product usage, we adopted the models of Dazarola et al. (2012) and Ketola (2005) as a framework for the current study (see Figure 2). The models describe the product usage life cycle in chronological order from before purchase to discarding or repurchase. Our reference model consists of seven phases of product usage: before purchase; purchase; unboxing; first-time usage; familiarisation; use; and disposal/repurchase.

Figure 2. Seven phases of the product usage life cycle in the study.

- Before purchase: This is a phase during which a user is aware of the existence of the product and product-related thoughts are developed. Visual contact between user and product is made through direct vision or through paper or virtual catalogues before the acquisition. The phase is usually accompanied by exploration of the product. Expectations are created about the experience of using a product or its features and benefits.

- Purchase: This is a phase in which the user purchases the product at a sales point with the purchase decision being based on all the acquired experience and benefits.

- Unboxing: During this phase, the package of the product is opened. It is an anticipatory moment for the user, who performs the ritual of using the product for the first time.

- First-time usage: This is a key event in user experience during which product features, installation, preparation, assembly and first usage are enabled for the first time.

- Familiarisation: During this phase, the user becomes familiar with operating the product and its primary functions. The product performs the main functions for which it was created and interacts with the user.

- Use: This is a phase when the user fully experiences the product over long periods of time. General opinions about the product are formed in this phase.

- Disposal/repurchase: This is the time when the final and physical separation between the user and the product occurs. It either does not perform its primary functions or it is not used any more. At this stage, it is thrown away, left for collection, sold, reused, recycled, or replaced by a newer model of the same product.

Method

Participants

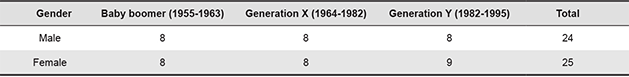

A total of 49 participants were recruited. Their ages ranged between 20 and 62 (M = 42.3; SD = 13.2) and 51% of the participants were female. The participants were recruited through social media and were paid for their contribution. As cases of positive user experience covering the whole product usage life cycle are the core material for the study, they were selected on the basis of the following criteria: anyone who had a product 3 that provided them with positive experiences, that they had used for more than a year but did not use it any more, or that was repurchased or repeatedly used after the previous one at the time of the study. The concept of positive experience was communicated to the participants as defined in the present study. In addition, as generation is the key to represent age, we included the variable generation with three categories: baby boomer (1955-1963), Generation X (1964-1982) and Generation Y (1982-1995). See the number and gender per category in Table 2.

Table 2. Participant distribution in terms of gender and generation.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire started with a brief introduction that described the aim of the study and asked about the participant’s gender and age. The first part of the questionnaire guided the participants to report their positive experiences in relation to products from the first time they encountered the product until the time of this study. They were presented with a set of guiding questions in the form of a love letter (Martin & Hanington, 2012) that asked about the age, appearance and character of the product, and then the time when the participants encountered the product, what happened, their strengths and weaknesses and the overall experiences with the product.

The second part of the questionnaire was meant to help the participants become well acquainted with the definitions of the five UX attributes as a means of a sensitisation exercise. First, the participants were asked to report which aspect of the product was critical in making them feel positive about it (i.e., any particular reasons): for example, I love the food processor because it is very safe and grinds very well. This was about their overall positive experience of the product before receiving the definitions of the five UX attributes. Then, they were instructed to rate the relevance of each of the five attributes on a 5-point Likert scale for the selected product. The definition of each attribute (e.g., aesthetics means the experience that results from the perception of sensorial qualities of a product) was given with product examples (e.g., the form and colour are beautiful; the sound is pleasant; it gives a soft and warm feeling).

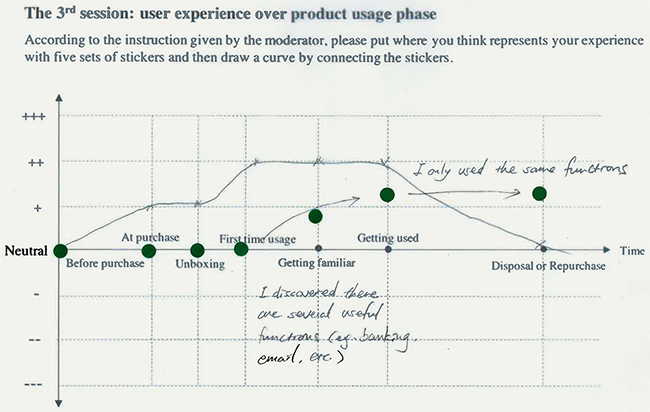

The third part of the questionnaire guided the participants to express their experiences throughout the product usage life cycle by using a template that visualises the positive and negative valence based on a bipolar, up-and-down pattern, a method often referred to as the UX curve, as shown in Figure 3 (Kujala et al., 2011). The vertical axis refers to the extent to which the participant’s experiences were positive or negative, based on a 7-point Likert scale: represented with +++ (very positive); ++ (moderately positive); + (slightly positive); 0 (neutral); − (slightly negative); −− (moderately negative); −−− (very negative). To quantify points marked by the participants, the template was designed to have a constant distance between the symbols: i.e., Very positive = 6 cm; Moderately positive = 4 cm; Slightly positive = 2 cm; Neutral = 0; Slightly negative = −2 cm; Moderately negative = −4 cm; Very negative = −6 cm from the x-axis. The vertical distance in cm from the x-axis to a marked point became the value for quantitative analysis. The horizontal axis refers to the seven phases of product usage based on the reference model. The participants subsequently added a transparent paper layer onto the template and marked how positive or negative they felt towards the product over time in terms of each of the five UX attributes.

Figure 3. An example of the questionnaire template:

Assessing the user’s instrumental experience over the overall user experience.

Procedure

The study was conducted individually at the Home Lab of UNIST, following two steps: (1) filling in the questionnaire; and (2) holding an interview. After a general introduction to the study’s objective, the participants were walked through each of the three parts of the questionnaire and guided to complete them. Next, a semi-structured retrospective interview was carried out by reviewing and referring to the participants’ answers to the questionnaire. The purpose of this was to ensure that their answers had been correctly given and to avoid the possible bias of the researchers while interpreting the data.

Data Analysis

The main focus of the analysis was on identifying whether product usage phases make differences in positive user experience and how that occurs. From the first part of the questionnaire, the products reported by the participants were identified and categorised. In the second part, cumulative data were obtained based on the question in which a critical UX attribute (i.e., contributing most to the positive experience with their product) was asked among the five attributes. The data were quantitatively analysed to obtain an overview of the distribution of the five attributes in their roles of facilitating positive experiences. From the third part of the questionnaire, the patterns of the positive experiences were gathered by using mean values of each attribute in each phase of the product usage life cycle. The same analysis was performed for overall use experience. After this, to identify the interrelation between overall user experience (hereafter, overall UX) and each attribute, Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted based on the mean values of each phase. Gender and age data were used to examine how the influence of gender and generation affected critical UX attributes. With the critical attributes, chi-square tests were conducted to identify the difference between male and female respondents and between generations.

Lastly, the mean values of overall UX and UX attributes in the product usage life cycle were compared to determine how gender and age make a difference. For gender, a Mann-Whitney U test was used; for age, Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed.

Results

First, we report the products chosen by the participants. Next, we describe how the five UX attributes are distributed in the positive experiences. Then, we report how the overall UX changes over the product usage phase and how it is related to the five UX attributes. Finally, we describe the influence of demographic factors on positive experiences over the product usage life cycle.

Products and Distribution of the Five Attributes in Positive Experiences

From the questionnaire, a total of 49 products were mentioned, one for each participant. The products that the participants mentioned were diverse, including smartphones, Bluetooth speakers, vintage dishes, kitchen knives, sofas, coffee machines, fashion items such as a backpack and a hat, cars, fountain pens, camping gear, novels, soaps, disposable diapers, and services such as an online game and a quick delivery service. The usage period of the products ranged from one year (e.g., earphones, tumbler and golf ball) to ten years (e.g., fountain pen, shaver and car). A Spearman’s Rank Order correlation analysis was conducted to explore how the period of usage is related to the five UX attributes over the product usage cycle. The result indicates that there is no statistically significant correlation between the usage period and the five UX attributes.

During the love letter exercise, the participants explained why they found their experiences with the products positive. One respondent (P4), for example, described “I went out with you (a pair of Nike shoes) when it rained and you were soaked wet … that night I remember spending all night with you and a hair dryer.” Considering their stories and detailed responses in relation to the questionnaire, the love letter exercise appeared to sensitise the participants effectively, helping them reflect their positive experiences with the products.

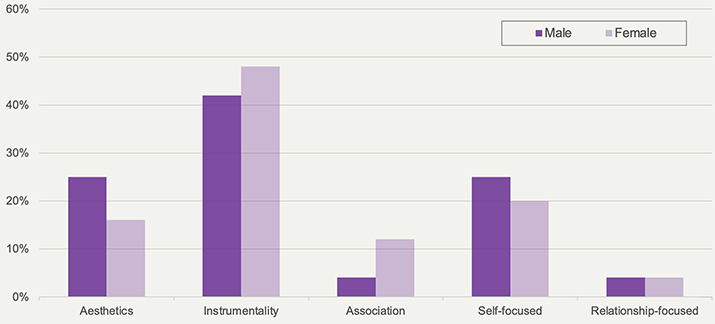

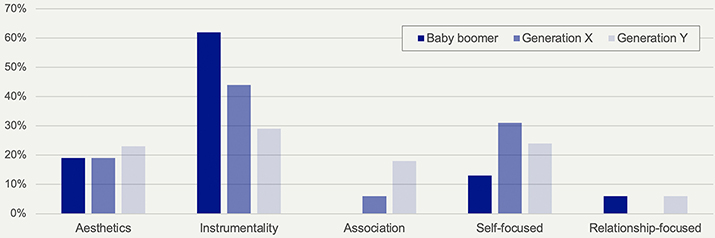

Among the five UX attributes, instrumentality was most frequently attributed to the positive experiences facilitated by the chosen products (45%). This was followed by self-focused identification (23%) and aesthetics (20%). Association and relationship-focused identification were least mentioned: 8% and 4%, respectively.

General User Experience over the Product Usage Cycle and Interplay with UX Attributes

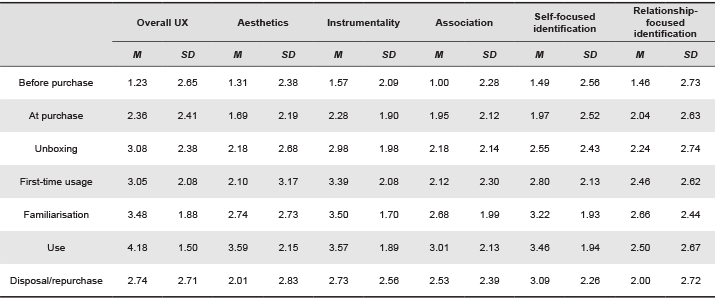

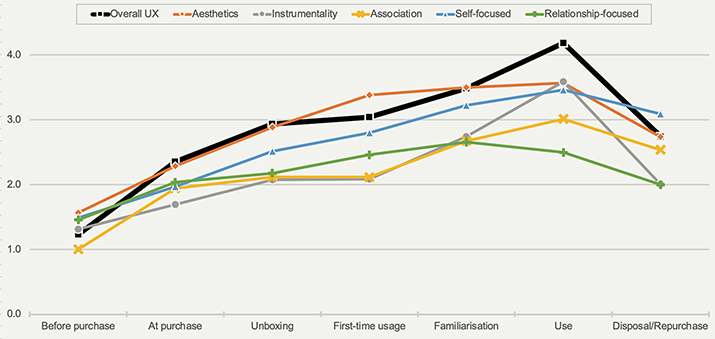

The mean values of overall UX curves changed over the product usage phases, as described in Table 3 and visualised in Figure 4. In the phase before purchase, the mean value was lowest (M = 1.23). Then, the value gradually increased until the phase familiarisation with the product (M = 4.18). The level of the general UX curve decreased until the disposal/repurchase phase (M = 2.74). All the individual UX attributes tended to follow the pattern of the overall UX except relationship-focused identification. In contrast to the other attributes, relationship-focused identification was highest in the phase of familiarisation.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of overall UX and UX attributes over the usage phases.

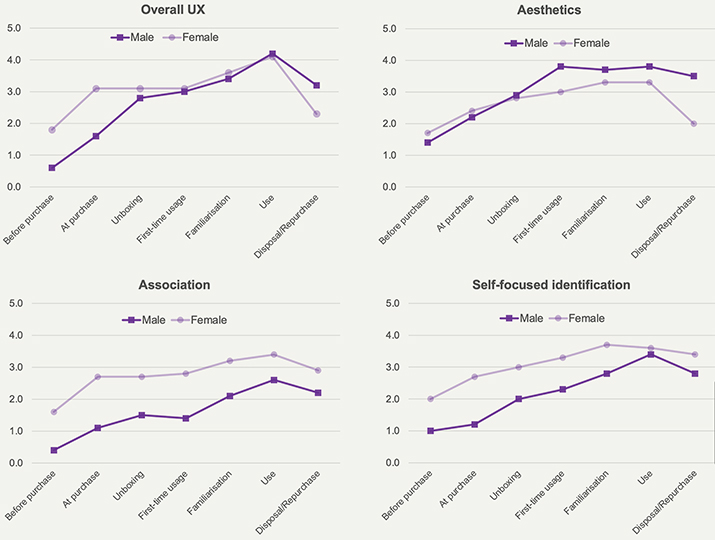

Figure 4. Trend of overall UX and five UX attributes curves over the product usage phases.

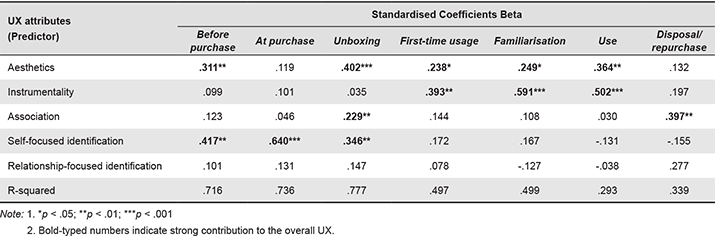

The relationship between overall UX and individual UX attributes was investigated using multiple linear regression. The results indicated that there was a strong causality between the levels of overall UX and the levels of individual UX attributes throughout the product usage phases (see Table 4).

Table 4. Results of multiple linear regression analyses of predictors of the overall UX.

In the phase before purchase, the results of the regression indicated that the model explained 71.6% of the variance. While sensory experience (B = .31, p < .001) and self-focused identification (B = .42, p < .001) contributed significantly to the model, the other attributes did not. However, at purchase, only self-focused identification was a significant predictor of overall user experience (B = .64, p < .001) as the regression model explained 73.6% of the variance. In the phase of unboxing, the regression model explained 77.7% of the variance and three UX attributes strongly influenced the overall UX level. Aesthetics showed the strongest causality (B = .40, p < .001), while self-focused identification (B = .35, p < .01) and association (B = .23, p < .01) showed a relatively moderate contribution. During the phase of first-time usage, instrumentality showed the strongest causality with the overall UX (B = .39, p < .01), followed by aesthetics (B = .24, p < .05). In this phase, the results of the regression indicated that the model explained 49.7% of the variance. The same trend was observed during familiarisation as well as the use phase. In the phase of familiarisation, instrumentality showed a strong causality with the overall UX (B = .59, p < .001), while aesthetics moderately contributed to the model (B = .25, p < .05). In the phase of use, instrumentality (B = .50, p < .001) showed a stronger causality than aesthetics (B = .36, p < .01). The results indicated that the model explained 49.9% in the phase of familiarisation of the variance and it was the lowest in the phase of use of the variance (29.3%). In the phase of disposal/repurchase, only association was a significant contributor to overall user experience (B = .40, p < .01) as the regression model explained 33.9% of the variance.

The overall results indicated that aesthetics and self-focused identification highly influenced overall positive user experience from before purchase until unboxing in the product usage life cycle. In contrast, instrumentality appeared to be the most influential in the latter phases of product use (i.e., first-time usage, familiarisation and use), while aesthetics played a moderate role. Unlike the previous phases, association seemed to have an influence only in the phase of disposal/repurchase.

Influence of Demographic Factors on Positive Experience over the Product Usage Life Cycle

Gender

The proportion of males for each UX attribute was not significantly different from the proportion of females across the five UX attributes (see Figure 5). According to the chi-square tests, the significance value (.799) was larger than the alpha value of .05. This suggests that the gender difference on appreciation of the five UX attributes was not statistically significant.

Figure 5. Percentages of the critical UX attributes given between the male and the female group.

To explore the influence of gender on positive experience in different phases of product usage, a Mann-Whitney U test was conducted. For the overall UX, there was a statistically significant difference in values for male (M = 1.57, SD = 2.32) and female respondents (M = 3.12, SD = 2.29) in the purchase phase only (p = .019). Female groups assigned a much higher value in this phase than the male group (see Figure 6). In addition, the influence of gender was investigated for individual UX attributes over the product usage phases. The results indicated that the gender difference was identified with aesthetics, association and self-focused identification.

Figure 6. Gender differences for overall UX and UX attributes over the product usage life cycle.

The influence of gender varied across the product usage phases. For aesthetics, the influence of gender was observed only at the time of disposal/repurchase (p = .018). Male participants (M = 3.47, SD = 2.42) gave higher values in the phase of disposal/repurchase than female participants (M = 2.03, SD = 2.55). Conversely, for the phases of purchase and unboxing, female participants gave higher values for association than the male group (female in purchase: M = 2.72, SD = 2.28 versus male in purchase: M = 1.14, SD = 1.62; female in unboxing: M = 2.80, SD = 2.00 versus male in unboxing: M = 1.54, SD = 2.13). The p values of the purchase and unboxing phases were .012 and .032, respectively. Concerning self-focused identification, the values of female participants (M = 2.71, SD = 2.23) were higher than the values of male participants (M = 1.20, SD = 2.61) in the purchase phase (p = .033).

The results indicated that, in general, the female participants were more positive towards their products before purchase. The female participants’ appreciation of aesthetics decreased sharply in the phase of disposal/repurchase. Throughout all the product usage phases, female participants reported higher values in the association and self-focused identification.

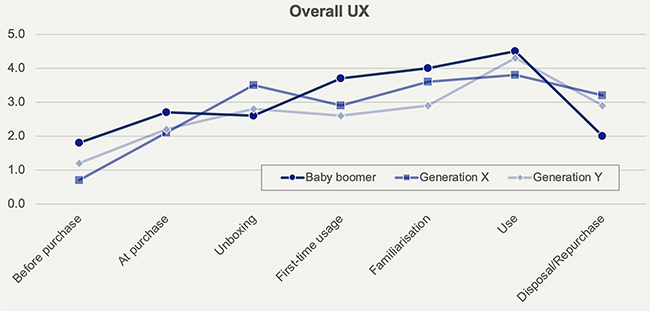

Age

The distribution of the critical UX attributes in positive experience showed that for the youngest group (i.e., generation Y), the extent to which they appreciated the five UX attributes was not noticeably different (see Figure 7). In contrast, instrumentality was highly acknowledged in older age groups. However, the differences among the three age groups (i.e., baby boomer, Generation X, and Generation Y) were not statistically significant. According to chi-square tests, the significance value (p = .470) was larger than the alpha value of .05. Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed that there were no strong correlations among the three age groups and the five UX attributes across the product usage phases (see Figure 8).

Figure 7. Percentages of the critical UX attributes between generations.

Figure 8. Mean values of the overall UX between generations over the product usage life cycle.

Discussion

While most literature on user experience has focused on understanding which aspects of products and users contribute to negative experiences with the aim of mitigating them (e.g., Kim, 2014; Klein et al., 2002), the current study had the opposite aim. The study explored which aspects of products and users are associated with positive experiences and, more specifically, how the product usage life cycle interacts with positive user experience and demographic factors, such as gender and age. Our main finding is that positive user experience of products varies according to product usage phases, but there is little difference in terms of gender and age. In this section, we discuss the key insights gained from the study in comparison with related work. We also discuss the opportunities that the study results may present to design practitioners in their efforts to design for positive experiences. The results will also be discussed in relation to studies that have explored how time and demographic factors interact with user experience.

The Five UX Attributes in Positive User Experience

The results indicate that among the five UX attributes, instrumentality, self-focused identification and aesthetics account for approximately 90% of the reasons why people regarded their products positively. Instrumentality accounted for almost half of the reasons and it appears that the attribute plays a critical role in facilitating positive experiences in product use. This is in line with our previous studies (Kim, 2014 ; Kim, & Christiaans, 2016) in which the focus was on negative user experience and instrumentality explained most of the complaints. A possible explanation is that instrumentality or task-goal of consumers (e.g., making a cup of orange juice with a blender) is learned through experiences and is driven by the self-identified goals of the consumer (Hoch, 2002). Therefore, instrumentality is more likely to be dominant in positive user experiences. Huffman and Houston (1993) also found that consumers’ memories improved when the experience was organised around their goal. In other words, the instrumental qualities of a product could be perceived more easily by users through function-related goals.

It is interesting that both self-focused identification and aesthetics were also often mentioned as reasons for a positive experience. Concerning self-focused identification, this is most likely a result of the characteristics of the experience and personal values lasting a long time and not changing easily. In line with Kim and Christiaans’ study (2012), the products that provided positive experiences in the current study tended to be often and repetitively used on a daily basis; high interaction density (i.e., products that are often and repeatedly used) strongly influences user experience. Similarly, Blom and Monk (2003) showed that frequently used products are more likely to be personalised, which lead to emotional attachment. Thus, this may explain why aesthetics was often mentioned.

Association and relationship-focused identification were found to contribute less to the overall evaluation of products facilitating positive experience from a long-term perspective. They tended to be brief over the product usage life cycle. That being said, association and relationship-focused identification are still essential for a positive experience that promotes users’ subjective well-being and personal identity: association allows people to recall their personal experiences that are important in their life (Philippe et al., 2012) and relationship-focused identification strengthens social identity in a way that gives the associated products the quality of having notable worth and relevance for the user (Casais & Desmet, 2016). Overall, the five attributes were inclusive enough to represent the reported positive experiences with products, which indicates the effectiveness of using the five attributes to describe positive experiences in human–product interactions.

Changes of Overall User Experience over the Product Usage Life Cycle

For the overall UX, it is noteworthy that self-focused identification is the strongest contributor to the overall UX from Before purchasing until Unboxing (see Table 4) and then the effect to the overall UX decreases rapidly towards the phase of disposal/repurchase. Why does a user’s overall experience already start in a positive state? It is perhaps because, before purchase, the user already has some expectations or has received recommendations related to the product in terms of its property (e.g., I liked the form and colour of the Nike shoes), brand (e.g., I was invited to the launch show and liked the purse from the brand Dotween), type (e.g., I have always been fond of a fountain pen), durability (e.g., I believed the bumper of the car would be strong enough), or function (e.g., The balls from Titleist perform better than the others). In the phase of purchase, the positivity of the experiences increased. A possible explanation is that a user is excited because they finally own the product or service (e.g., I finally owned it; I was so excited to have the new one). In the phase of unboxing, it seems that the positive experience at purchase lasts (e.g., I was also pleased to unbox because I already purchased). In addition, unpacking influenced the increase of the value (e.g., The package was made of recyclable materials, which I highly valued from a sustainability point of view). However, the incremental increase slows down with first-time usage. A general explanation for this decrease could be a gap between expectations and reality in terms of what the user may have expected from the product and what the experience actually delivered. Some cases showed that in actual use, a higher cognitive load was demanded to learn how to use the product (e.g., It was challenging to figure out how to change the Bluetooth setting) and the aesthetics (i.e., sensory experiences) were not as positive as expected.

The next overall positivity increases again in the phase of familiarisation. This result may be because users feel more comfortable as the products become integrated into their daily lives (e.g., I can’t wear other shoes because these shoes became very comfortable; My smartphone keeps my to-do list and schedule well-organised; and The wallet has grown on me as the leather ages). The increase in the use phase is maintained as in the previous phase. It seems that users may have increasingly positive experiences due to product familiarity or intimacy (e.g., It was like my close friend) and durability (e.g., No breakdown and very durable). Even in the case of breakdown, some participants appreciated the quality of after-sales service (e.g., Their warranty service was decent, so I am still satisfied with the product). After long usage, the positivity of overall user experience drops rapidly and, as a result, users finally dispose of their products or repurchase them. A possible explanation for this is that the product is seen as less able to fulfil a function as expected (e.g., It is dented and its function is impaired) or the expense to maintain the product is too high (e.g., Better to buy a new one because the maintenance cost was too much).

Considering the overall results, our research implies that a user’s overall experiences are already positive even before purchasing the products that they will use over a long period. Although this initial experience of the product is formed, the overall experience decreases while the user becomes acquainted with the product. Once it is familiar to the user, attachment appears to form and lasts during the remaining usage period of the product with an incremental increase in overall experience.

Relation between Product Usage Phases and UX Attributes

The results indicate that, until the phase of unboxing, all UX attributes except instrumentality and relationship-focused identification seem to contribute to the overall UX. However, from then, only particular attributes are related to the users’ positive experiences. During before purchase and purchase, appreciation of the products to which people are attached is associated with self-focused identification (e.g., I purchase organic food because health is very important to me). This is likely to be a result of personal value being a strong determinant of purchase intention (Cronin et al., 2000; Kim & Chung, 2011). However, aesthetics was observed as a contributor to the overall positive experience at the phase of before purchase, not at purchase. This indicates that aesthetic pleasure resulting from sensorial perception is highly appreciated even before purchase and in many cases leads to a purchase decision (Kim et al., 2016). At the unboxing phase, self-focused identification is still important but aesthetics seems to become the most influential in the perception of overall UX. Association also contributes to the overall UX (e.g., It reminded me of the resourceful sales person while unboxing; There was a letter of apology due to delayed delivery in the package; It was my first smartphone). In particular, association at this phase was mostly about the events that had happened from before purchase to unboxing.

From the moment in which a product is used for the first time, instrumentality becomes more critical, while the aesthetics still affects the overall UX. After these phases (from familiarisation to use), the same pattern is shown in relation to the overall experience. In the phase of disposal/repurchase, association shows a significant contribution to the overall UX. Once the user starts to use the product, instrumentality seems to be the major contributor to the overall experience. Association could explain why they still felt positive about the product in the phase of disposal/repurchase.

On the basis of these patterns, we conclude that (1) the critical attributes of positive user experiences differ to a large extent according to the phase of product usage, and (2) it is important for designers to consider the different patterns of the UX attributes in different usage phases in generating positive experiences. Our study showed that instrumentality and aesthetics play a main role in positive experiences throughout product usage, while the importance of the other attributes decreases after first-time usage, except for an increase in the importance of association in the phase of disposal. The reason might be that instrumentality is hard to depreciate due to the basic goal of owning and using the products. This could also explain why people repurchase the same product or service (i.e., when a product or service does not function properly, people would not purchase it again). In one of our previous studies (Kim, 2014), instrumentality was the major reason for people’s dissatisfaction while using their products. This implies that instrumentality plays a central role in both positive and negative user experiences.

In the meantime, aesthetics serves as a strong contributor to the overall UX from the early phases of the product usage life cycle until getting used; it is highest at the moment when a product is unpacked. In this phase, the sensory qualities (e.g., the appearance and materials of a product) were most appreciated in the interactions with the product. Although pleasure stimulated by material qualities of a product does not last long (Roto et al., 2011), given the fact that appreciation of a product’s material qualities arises through frequent and repetitive daily interactions, aesthetics appears to be important in generating positive experiences throughout the entire product usage life cycle. Self-focused identification is also an important contributor to the overall positive experience, mainly in an early phase of product usage. A possible explanation is that self-focused identification expected from the product has already influenced the purchase intention before first-time usage. Association is a strong contributor to overall experience in the early phases as well as in the phase of disposal/repurchase. The user’s memories or prior experiences with a product seem to contribute to the overall positive experience before first-time usage. Association also plays a role when users dispose of a product due to the memories that have accumulated over the previous phases.

These findings are contrary to previous studies, which suggested that over time, the importance of familiarity, functional dependency and emotional attachment increase sequentially in the product usage life cycle (e.g., Karapanos, 2013; Karapanos et al., 2010; Kujala et al., 2013; Mugge et al. 2005; Mugge et al. 2008; von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff et al., 2006). The present study confirms that instrumentality such as learnability, usefulness and usability is considered important in the phase of orientation and corporation; the product’s usefulness becomes the major factor impacting our overall evaluative judgements in the phase of incorporation. For aesthetics, however, the result seems divergent; its contribution to positive experiences does not taper off over time. This implies that aesthetics as a hedonic dimension may still play an important role in the perceived quality of the product, particularly with positive experience over time. Unlike Hassenzahl (2003), who found that hedonics rather than pragmatics drive bonding to a product (i.e., strong positive relationship), the present study showed that both positive hedonic and pragmatic experience are a strong predictor of long-term positive experiences.

The current study indicates that self-focused identification is critical in the purchase phase. Unlike the findings of Karapanos (2013), self-focused identification is not a significant predictor of increased positive experience from the phase of orientation. Relationship-focused identification is also hardly considered as a contributor in relation to the overall positive experience. Considering the pleasure sparked by extrinsic motivation, e.g., safeguarding or exaggerating one’s social images by possessing or consuming certain brands (Peters et al., 2018), relationship-focused identification appears to be limited in generating long-lasting positive experiences in our study.

These contrary findings can possibly be attributed to the product samples and the data collection method. While the current study employed self-selected products delivering positive experiences, Karapanos (2013) employed iPhone, a novel consumer electronic product at the time of the study. The study was conducted based on data collected during the four weeks after purchase, adopting self-report techniques such as day reconstruction and experience narration. Similarly, Fenko et al. (2011) asked people to describe their sensory experiences with different consumer products and rate the importance of different sensory modalities during the first year of usage. They found that at the moment of purchase, vision is the most important modality, but during usage over a month, the other sensory modalities such as touch and sound gained more importance. After one year, vision, touch and sound were found to be equally important. The study suggested that designers need to give attention to the relative importance of different sensory modalities that change over time.

These studies offer valuable insights into the underlying aspects of design that contribute to positive experiences over time. However, they tend to focus on particular product types (e.g., smartphone) or UX attributes (e.g., sensory modality) in isolation, which limits providing a structured overview of the interplay between user characteristics and UX attributes in facilitating positive experiences over time. The present paper focused on long-term positive experiences collected by means of recalled memories structured by the UX curve method. In particular, each of the five individual UX attributes were holistically measured over the seven phases of product usage life cycle, which allowed us to systematically investigate determinants of positive experiences over time.

Influence of Demographic Factors across the Five Attributes

There was no significant gender difference in terms of the critical UX attributes that explained why people regarded their experiences with the products as positive. These findings are in line with the results of our previous study on the influence of user characteristics on negative user experience of consumer electronics (Kim & Christiaans, 2016). This implies that gender difference would not be a critical factor to be considered, particularly when it comes to the major reasons for a product or service receiving a positive user experience. Although age made no significant difference, we could identify an interesting pattern between generations. The youngest generation (i.e., Generation Y) seems to consider a broader range of reasons for finding their products positive than the oldest generation (i.e., baby boomers). Instrumentality explains the reasons for this, particularly for baby boomers, while all five attributes appear to be similarly distributed for Generation Y. Baby boomers are more positive towards the functional aspects of their products than Generation Y. Appreciation of association was only observed by the younger generations. This could imply that younger people are more inclined to take diverse experiences into consideration while the old generation mainly pays attention to what they can achieve through using a product.

Influence of Demographic Factors over the Product Usage Phases

When comparing positive experiences over the product usage phases, some differences between genders were observed. In the overall UX, the females’ mean value was higher than the males’ mean value in the phase of before purchase only. Females are more sensitive to and expectant about what it will be like to own or use the product before or at purchase (Maclnnis & Price, 1987). Another possible explanation is that females may spend more time and effort on searching than males, leading them to be aware of advantageous aspects of the products (Bakewell & Mitchell, 2006; Denis & McCall, 2005). If that is the case, females, to a greater extent, will appreciate products more prior to purchase.

Gender appears to influence the ways in which people appreciate different UX attributes in each of the product usage phases. In the purchase phase, females perceive association and self-focused identification as more important than males. While a product is being used (i.e., from first-time usage to use), interestingly, there was no difference in the UX attributes between males and females. This partly corresponds to the finding of our previous study (Kim & Christiaans, 2016) in which gender had no influence on negative sensory and instrumental qualities in product use. Besides, age seems to make little difference in experiences over time in terms of overall UX. In addition, no significant difference appears across the product usage phases in terms of the five attributes.

Influence of Product Characteristics: Hedonic and Pragmatic Qualities

User experience is the outcome of the complex interplay of the user, product and use context, and it changes over time (Merčun & Žumer, 2016). We examined the effect of gender and generation as user characteristics in positive user experience. However, in the present study, the characteristics of product types and use context were not taken into consideration because of the heterogeneity of the product types chosen by the participants. Considering the fact that user experience varies depending on the perception of the product’s hedonic and pragmatic qualities (Hassenzahl, 2007; Hassenzahl et al., 2002), it would be interesting to see the patterns of positive experience over time through the lens of these two qualities. To gain a preliminary insight into the influence of pragmatic and hedonic characteristics over the product usage cycle, we compared ten product types that were representative of either pragmatic (five products) or hedonic (five products). The selection of the product types was loosely based on the categorisation of products (Jordan & Persson, 2007), which reflects the different needs and expectations people have towards different types of products.

The products having a strong pragmatic quality were kitchen appliances (e.g., blender), personal care appliances (e.g., electric shaver) and stationary (e.g., pencil), whereas those with a strong hedonic attribute were fashion-related products (e.g., designer sneakers and fashion wristwatch) and services (e.g., online game, TV media service and music streaming service). The mean values of both the pragmatic and hedonic product group over product usage cycle were compared by running a t-test analysis. Statistical differences were identified between the two groups in instrumentality, aesthetics and association over the usage life cycle. For the pragmatic product group, the instrumentality of a product was more appreciated than the hedonic group until purchasing the product. However, the appreciation of instrumentality drastically dropped at the phase of the unboxing and first-time usage, then it incrementally increased until the phase of use. In contrast, the appreciation of instrumentality in the hedonic group incrementally increased although the overall level was lower than the pragmatic group until purchasing the product. We suppose that high expectations play an important role in positive experience until before unboxing and first-time usage. Probably, pragmatic products are initially expected to function better and be easier to use, while such instrumental qualities are not highly expected in hedonic products.

For aesthetics, the hedonic product group showed a surge until the first-time usage while the experience fell after the first-time usage. Namely, positive sensory experience from hedonic products lasts until the pleasure is experienced at the very beginning of the usage. This observation could be explained by the phenomenon of hedonic adaptation (Lyubomirsky, 2011), which happens when users quickly become accustomed to the pleasure elicited by the product and they eventually find it mundane. However, aesthetics in the pragmatic product group was steady throughout the usage life cycle. This is probably because aesthetics for the pragmatic product group was not mainly considered critical from the beginning to the end of the usage life cycle. In addition, appreciation of association incrementally increased in the hedonic product group, while it was relatively steady in the pragmatic product group during the usage period of the product.

These findings are in line with previous research showing that both pragmatic and hedonic qualities contribute to the overall positive experience of the product (Hassenzahl, 2001; Hassenzahl et al., 2002) and the overshadowing effect of hedonic aspects over time (Minge, 2008). The implications of the findings are that different design strategies need to be adopted according to the characteristics of a product and users’ expectations in different phases of product usage in order to augment and prolong positive experience. Products that are more utilitarian in nature need more attention paid to identification of instrumental expectations in the product development process (i.e., functionality and usability). Meanwhile, products characterised by the quality of hedonics require more consideration on how to prolong or continue to stimulate sensory experiences, such as appearance, sound, touch, for the long-term and repetitive use of a product. Building on the preliminary findings, we aim to advance the understanding of the influence of pragmatics and hedonics in positive experiences by conducting an in-depth study in more controlled settings in the future.

Influence of Product Characteristics: Usage Period

As another variable representing product characteristics, the period of usage was also taken into account to examine how it makes a difference among the five attributes across product usage life cycle, particularly the relation to association in the sense that time plays an essential role because the experience is based on memories and episodes that are largely shaped by how long the products were used. However, the result indicates that there is no statistically significant correlation between the period of the usage and any of the UX attributes. This implies the period that a product was used hardly affected the prominence of particular UX attributes across the product usage life cycle. The result is in line with the study by Mugge et al. (2005) on product attachment, which showed that time is not an essential factor constituting the attachment to a product. The results, however, need to be interpreted with caution. They may have been affected by the way the data were collected (i.e., self-report based on recalled memories). Recollecting past experiences, people are most likely to remember events that took place at the very beginning and that have been recently experienced (i.e., the primacy and recency effect; Baddeley & Hitch, 1993) and peak positive moments (i.e., duration neglect; Fredrickson & Kahneman, 1993) in the user–product relationship, regardless of the number of episodes.

Implications for Design Practice

The study findings help us understand: (1) what attributes are related to; and (2) how the product usage life cycle and demographic factors interact with positive user experience. The results can serve as a valuable reference for design professionals in their endeavour to systematically generate positive experiences.

In general, our results show that positive user experience is already formed ahead of purchase and incrementally increases, whereupon it rapidly decreases towards the phase of disposal/repurchase. Particular attributes are related to the increase of positive user experience in each of the product usage phases. Until purchasing a product, self-focused identification and relationship-focused identification play a critical role in forming a positive experience. Aesthetics is emphasised in the phase of unboxing. From the first-time usage, the main contributor to the incremental increase in positive user experience is instrumentality. Decreased positive user experience, especially in aesthetical and instrumental aspects, leads to the disposal of a product.

Given the fact that instrumentality is a major contributor to positive experiences, it seems to be essential to identify users’ instrumental needs and concerns in using the products in each of the product usage phases and address them accordingly (e.g., addressing easy to open at the stage of unboxing). While being less influential than instrumentality, self-focused identification is noteworthy, especially in envisioning users’ experiences in the early phases of product usage (e.g., purchasing and unboxing). Thus, it is worth enabling people to perceive that the experience with a product coincides with users’ personal values or social norm. For instance, what a product offers could be something sustainable (e.g., using recyclable materials for packaging or enabling people to use the product in a sustainable manner).

In the design literature, association and relationship-focused identification have long been considered to add value to user experience. Accordingly, several design strategies have been proposed (e.g., Casais et al., 2015; Mugge et al., 2008). For instance, how to use symbolic meaning of a product to influence users’ behaviours. The present study showed that the overall contribution of association and relationship-focused identification was relatively low and they were particularly appreciated before and at purchases. Given the results, it would be more effective for designers to apply those strategies to the design of the product and other associated experiences in these two phases (e.g., packaging, branding, and marketing).

The results indicate that the oldest generation highly appreciates instrumentality throughout different stages of the product usage life cycle, while younger generations do not necessarily do so. This finding could help designers when age is a key issue for the target user group, that is, younger people are more inclined to take diverse experiences into consideration while the old generation mainly give attention to what they can achieve through using a product. For instance, in developing a product targeted for the elderly (e.g., a smart home system to promote their independent life), more attention has to be paid to anticipated functions, easy to use and learnability while using the product. Maintaining functional qualities of a product, personal values and episodes that could be associated with the product need to be taken into serious consideration in case younger people are the main target user group.

Considering that instrumentality can contribute to achieving behavioural goals, performing specific tasks with efficiency (e.g., setting a time with an alarm clock) can help the user reach their behaviour goals (e.g., having punctuality by arriving at work or appointments on time). For example, how well a fitness tracking device helps the user take care of their health can be, to a large extent, influenced by the instrumental quality of the product. However, it is also important to note that a successful implementation of instrumentality does not always guarantee the fulfilment of behavioural goals. A superbly designed timer may make the cooking process more efficient (i.e., instrumentality), yet the timer on its own would not help the person make more creative cooking recipes (i.e., behavioural goals). This implies that when addressing the instrumental aspects of a product, designers should consider how task-oriented and behaviour goals are related. Thus, to better support instrumental experience, developing an in-depth understanding of users’ needs and expectations in both levels (i.e., task and behavioural goals) is crucial.

In addition, the study results can be useful when developing a product that is gender dependent. The study identifies female users as having a higher appreciation of their products than male users before purchasing. Female users appear to have more appreciation for self-focused identification and association until unboxing. However, once the products start to be used, there is no gender difference. These differences between genders could be considered when envisioning the ways in which products are communicated and used in the early phases of product use (e.g., as a means of marketing and product packages). In summary, the findings provide designers with a structured overview of positive user experience through the lens of the phases of the product usage life cycle and the influence of user characteristics. The findings can serve as a source of inspiration and reference in holistically addressing intended users’ needs and expectations in different phases of product use.

Limitations and Future Studies

The paper provides insights into how the product usage life cycle and demographic factors interact with positive user experience through an empirical study. Nonetheless, it is not without limitations. One limitation is that all the participants were from South Korea. The concept of what makes us feel positive or happy can vary from country to country and culture to culture. Research has suggested that while personal feelings of pleasure are highly valued in Western cultures, in some areas of Africa, they are more about shared experiences within a community (e.g., family). East Asian cultures tend to regard positive experiences as social harmony (Hochschild, 1983). Concerning these cultural differences in terms of the concept of positive experience, we acknowledge that we should be cautious about generalising the findings.

Another limitation is that the data collected from the UX curve method were based on the participants’ recall of positive experiences. The data might be limited in reflecting the participants’ actual experience vividly (e.g., subtle aesthetic experience) because of the inevitable bias caused by the recalled memory. According to Fredrickson and Kahneman (1993), our recollection of pleasurable moments is reconstructed mainly based on peak moments and endings, but the duration of the pleasurable experience is minimally related to the overall recollection. What matters most in a memory is whether the peak moment and ending are good (Gilovich et al., 2015). This could imply that some of the findings would rest on the peak and ending experience of each phase. Therefore, we invite additional studies to utilise approaches that avoid or minimise memory biases (e.g., moment-to-moment data collection through experience sampling; Hektner et al., 2007).

Lastly, we did not include product characteristics as one of the assumed influential factors in positive user experience because of the intricacy of categorising them; with the emergence of multifunctional products and the experience dependency on use context, the boundary between categories has become blurry. This may be a limitation of the study, considering that users tend to have different expectations of different product types (Jordan & Persson, 2007; Vink, 2005). In a future study, the influence of product characteristics such as product type including the pragmatic/hedonic perspective should be considered.

Conclusion

Most studies in user experience have dealt with overall experience, not paying close attention to different usage phases and user characteristics. The current paper has shown that the positive user experience is dependent on particular UX attributes over the product usage life cycle. The study’s main contribution is the overview of the influence of the UX attributes in different usage phases on positive user experience. The findings can provide design researchers and professionals with a developed understanding of the formation of positive user experience that can be utilised in further research and the product development process.

Acknowledgments

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the participants who joined the study presented in the paper. Moreover, we would like to thank the editor, the reviewers and particularly Henri Christiaans and James Self for their constructive feedback on earlier versions of this paper. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019R1G1A1100779) and Cornell University’s translational research and outreach fund.

Endnotes

- 1. Considering that product types (or categories) have become harder and harder to define, it seems that there is no definite variable that can solely represent product types. Thus, product types were not considered as a variable in the study.

- 2. The attributes were defined in a two-stage procedure. The first stage was to create a list of attributes of user experience based on the literature in design research and HCI, and the second was to cluster these into the five attributes based on their similarities (Kang et al., 2016).

- 3. In this paper, product represents a continuum of different design solutions that encompass multiple manifestations and scales—for example user interface, product, and service.

References

- Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1993). The recency effect: Implicit learning with explicit retrieval? Memory & Cognition, 21(2), 146-155.

- Bakewell, C., & Mitchell, V.-W. (2006). Male versus female consumer decision making styles. Journal of Business Research, 59(12), 1297-1300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.09.008

- Blom, J. O., & Monk, A. F. (2003). Theory of personalization of appearance: Why users personalize their PCs and mobile phones. Human-Computer Interaction, 18(3), 193-228.

- Calvo, R. A., & Peters, D. (2014). Positive computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- Casais, R. M., & Desmet, P. (2016). Symbolic meaning attribution as a means to design for happiness. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Design and Emotion (pp. 27-30). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: The Design & Emotion Society.

- Casais, M., Mugge, R., & Desmet, P. M. A. (2015). Extending product life by introducing symbolic meaning: An exploration of design strategies to support subjective well-being. In Proceedings of the Conference on Product Lifetimes And The Environment (pp. 44-51). Nottingham, UK: Nottingham Trent University, CADBE.

- Chen-Yu, J. H., & Seock, Y. K. (2002). Adolescents’ clothing purchase motivations, information sources, and store selection criteria: A comparison of male/female and impulse/nonimpulse shoppers. Family and Consumer Science Research Journal, 31(1), 50-77.

- Cronin, J., Brandy, M. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193-218.

- Dazarola, R. H. J., Torán, M. M., & Sedra, M. C. E. (2012). Interactions for design: The temporality of the act of use and the attributes of products. In Proceedings of the 9th NordDesign Conference. Aalborg, Danmark: Center for Industrial Production, Aalborg University. Retrieved from https://www.designsociety.org/publication/38554/

- Dennis, C., & McCall, A. (2005). The Savannah hypothesis of shopping. Business Strategy Review, 16(3), 12-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0955-6419.2005.00368.x

- Desmet, P. M. A., & Hekkert, P. (2007). Framework of product experience. International Journal of Design, 1(1), 57-66.

- Desmet, P. M. A., & Pohlmeyer, A. E. (2013). Positive design: An introduction to design for subjective well-being. International Journal of Design, 7(3), 1-15.

- Donoghue, S., & de Klerk, H. M. (2006). Dissatisfied consumers’ complaint behavior concerning product failure of major electrical household appliances: A conceptual framework. Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Science, 34, 41-55.

- Fenko, A., Schifferstein, H. N. J., & Hekkert, P. (2011). Noisy products: Does appearance matter? International Journal of Design, 5(3), 77-87.

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Kahneman, D. (1993). Duration neglect in retrospective evaluations of affective episodes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(1), 45-55.

- Gilovich, T., Keltner, D., Chen, S., & Nisbett, R. E. (2015). Social psychology (4th ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Han, S. H., Yun, M. H., Kwahk, J., & Hong, S. W. (2001). Usability of consumer electronic products. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 28(3-4), 143-151.

- Hassenzahl, M. (2001). The effect of perceived hedonic quality on product appealingness. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 13(4), 481-499.

- Hassenzahl, M. (2003). The thing and I: Understanding the relationships between user and product. In M. A. Blythe, K. Overbeeke, A. F. Monk, & P. C. Wright (Eds.), Funology (pp. 31-42). Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Hassenzahl, M. (2007). The hedonic/pragmatic model of user experience. In E. Law, A. Vermeeren, M. Hassenzahl, & M. Blythe (Eds.), Towards a UX manifesto (pp. 10-14). Brussels, Belgium: COST.

- Hassenzahl, M. (2010). Experience design: Technology for all the right reasons. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

- Hassenzahl, M., Platz, A., Burmester, M., & Lehner, K. (2002). Hedonic and ergonomic quality aspects determine software’s appeal. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (pp. 201-208). New York, NY: ACM.

- Hassenzahl, M., & Tranctinsky, N. (2006). User experience: A research agenda. Behavior & Information Technology, 25(2), 91-97.