Social Interaction Design in Cultural Context:

A Case Study of a Traditional Social Activity

Institute of Applied Arts, National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu, Taiwan

With the growth and development of information and communication technology, relationships, communities and cultures have been dramatically affected, especially as a result of the increasing accessibility and speed of communication platforms. However, as people incorporate these emerging technologies into their social interactions, there results a tendency to lose touch with social nuances, cultural values, and the characteristics of traditional society. In this study, it is argued that social activities are inherently embodied in a cultural context. Therefore, a field study of tea drinking, as a traditional social activity in Taiwan, is presented with the purpose of revealing the abundant cultural features of this activity. Because these features merge with and influence people's social lives, developing a deeper understanding of this relationship could serve to enrich computer-mediated communication or interaction designs in the future. In this study, multiple user experience research methods are applied in exploring Taiwan's tea drinking customs, and, based on the findings, an enhanced cultural model is proposed to show the cultural significance of this activity. In addition, several design implications for software related to social interaction and cultural inheritance are offered. It is concluded that the cultural characteristics of a society should be a key issue in developing interaction designs.

Keywords – Contextual Inquiry, Cultural Differences, Social Computing, Social Interactions.

Relevance to Design Practice – The model presented in this research underscores that people's behaviors, attitudes, and motives are greatly influenced by cultural context. This model could be applied to social interaction designs for a specific region or to achieve intercultural competence.

Citation: Huang, K. H., & Deng, Y. S. (2008). Social interaction design in cultural context: A case study of a traditional social activity. International Journal of Design, 2(2), 81-96.

Received March 31, 2008; Accepted July 24, 2008; Published August 31, 2008

Copyright: © 2008 Huang and Deng. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

*Corresponding Author: Kohsun@csie.nctu.edu.tw

Introduction

The rapid expansion in Taiwan of information and communication technology, mobile communication devices and the Internet has played a definite and considerable role in people's social lives. The accessibility to various emerging communication media, as well as the speed of communication that these provide, has changed not only people's cultural and local living contexts but also their interpersonal relationships. These developing technology devices and applications both support new platforms for communication and offer numerous possibilities for an unprecedented increase in social interactions. At the same time, these interactions have taken on different features and characteristics with different media. There are now a variety of new social communities, virtual and physical (Wellman & Hampton, 1999; Preece & Maloney-Krichmar, 2003). In this research, we argue that social activities are inherently embedded in a cultural context. However, social nuances, cultural values, and characteristics of traditional society are not generally taken into consideration in the pursuit of developing new technologies for social interaction. For this reason, a field study of a traditional social activity in Taiwan is presented with the idea of identifying the abundant cultural features of this activity. An understanding of these features, which merge with and influence people's social lives, could serve to enrich computer-mediated communication or information designs in the future.

In the past twenty years, computer-mediated devices, with their powerful capacity for organization, have been used for numerous and diverse tasks. They do help people to work more systematically and effectively. Information technology applications, moreover, have been developed and redesigned for different purposes. However, some unexpected forms of social interaction and other side effects have emerged which have slowly been adapted and incorporated into people's lives (Ranson et al., 1996; Hutchinson et al., 2003). For instance, the main functions supported by personal blogs have changed from traditional information disclosure to information sharing and exchanging. In addition, the development of community diaries and collaborative blogging present evidence of rich sociality and communicative competence (Krishnamurthy, 2002; Nardi, Schiano, & Gumbrecht, 2004). In fact, personal on-line diaries not only serve as a means to record one's experiences and express one's emotions, but consequently also reflect one's attitudes and expectations toward society as a whole and in relation to one's cultural context (Herring, Scheidt, Bonus, & Wright, 2004; Kumar, Novak, Raghavan, & Tomkins, 2004).

In the related research fields of Human Computer Interaction and Computer Supported Cooperative Work, the development of software and applications has shifted from a focus on efforts that simply support explicit work tasks and coherent collaboration to a focus on online communities and their social characteristics (Greenberg & Marwood, 1994; Grudin & Palen, 1995; Ackerman, 2000). It has thus become of great importance to comprehend the complex social interactions that take place in a real context in these online communities. Recently, many of the popular computer terms and concepts that are extensively discussed, such as web 2.0, social software and social computing, all share a focus on the relationship of technology, interpersonal contact, and social communities (Hughes, Randall, & Shapiro, 1993; Kensing & Blomberg, 1998).

Due to unavoidable trends of globalization, many imperative needs and challenges related to cultural differences have emerged and need to be confronted. In different cultures and societies, the extent of personal social needs is quite different (Gudykunst & Ting-Toomey, 1988; Ji, Peng & Nisbett, 2000; Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001). Individual social attitudes, such as those related to a sense of belonging and identification, individual distance, emotional connections, and a sense of community, rely heavily on one's social context and cultural background (Hofstede, 1980; Hofstede, 1991; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Hence, the fundamental issues of technology media or online application development have extended from traditional usability problems to wider social aspects of interpersonal contact, information sharing, participation and culturally inherent needs (Herman, 1996; Yeo, 1998; Barber & Badre, 1998; Clemmensen et al., 2007). Based on theories in sociology, cognitive psychology, and content analysis, many researchers have pointed out a lack of consideration of cultural preferences, such as for colors, metaphors, or narrative layout, within existing online software (Marcus & Gould, 2000; Okazaki & Rivas, 2002; Chau, Cole, Massey, Montoya-Weiss, & O'Keefe, 2002; Li, Sun, & Zhang, 2007).

In addition to this lack of awareness of cultural preferences in interface design, what we wish to argue here is that the emerging technology itself and the social interactions it supports basically fall short when it comes to cultural concerns, including those that relate to users' perceptions and attitudes toward technology applications and the potential reasons to use them as communication media. Therefore, this research presents the case of tea-drinking customs, which are part of a particular traditional activity in Taiwan. The study applies multiple user experience research methods, which include practical observations and qualitative analysis by undertaking contextual inquiries and in-depth interviews. These methods could reveal different characteristics of personal perceptions in relation to the overall cultural context. Based on the findings, an enhanced model for the cultural considerations of social interactions is proposed, a model that could provide researchers and designers with a specific direction for examining the effects of culture upon general social activities. In addition, the potential applications to information science are also presented.

This paper proceeds in four parts. First, it provides an overview of online application development and some cultural issues of the field. Then, it presents a case study of tea-drinking activities in Taiwan with the intention of revealing the kinds of cultural and nuanced perceptions that are ignored in most computer-mediated software. In addition, an enhanced cultural model is also proposed. Finally, design implications with regard to enhancing Internet applications or mobile devices in the future are suggested. Some potential solutions for maintaining social interactions in traditional culture in Taiwan are also addressed.

Cultural Dimensions of Technology Development

Today, innovative technology, mobile communications, and the Internet play a role in most people's daily lives, being applied in diverse directions. As a result, social activities, cultural values, and the overall social fabric have been unavoidably influenced, particularly in Asian countries, where cultural traditions have been slowly fading away.

On the other hand, cultural differences directly influence decision-making when it comes to the ambitious target of globalization for many commercial software and online applications (Marcus, 1993; Marcus & Gould, 2000). Cultural preferences have become one of the most significant subjects and focuses of technology development, as it slowly turns away from issues of usability to issues of fulfilling users' cultural and social needs (Bourges-Waldegg & Scrivener, 1998; Strøm, 2006). In the next stage of technology development, it can be expected that the most essential concern will be to comprehend the needs of users all around the world, with regard to differences in language, customs, and behavior. In this section, several different aspects of such cultural issues will be discussed separately.

Cultural Aspects of Globalization

Hofstede (1980) defines culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another.” A culture can be distinguished as a set of shared characteristics within a group of people, and these characteristics include thoughts, values, and behaviors (Choi, Lee, Kim, & Jeon, 2005). In addition, cultures are primarily formed by specific social facts, including religion, politics, rituals, values and language (Searle, 1995; Bourges-Waldegg & Scrivener, 1998). For the purpose of human–computer interaction, Honold (2000) also defines culture based on definitions provided by Hofstede (1980), Ratner (1997), Shore (1996), and others. He indicates that culture does not determine the behavior of individuals but it does point to probable modes of perception, thought, and action. Culture is therefore both a structure as well as a process. Furthermore, culture manifests itself in cultural models, which are acquired through interaction with the environment.

In the past decade, user-centered design has become the essence of human-computer interface design, interaction design, and industrial design. In these domains, designers and system developers focus on comprehending and meeting people's specific requirements. However, for the purposes of globalization, the online application design of most commercial pursuits has been forced to confront the serious issues that relate to cultural differences, due to the great variety globally in preferences, motivations for accessing media, personal perceptions and values of users. These are definitely different from one culture to another.

Marcus (2002) addresses the fact that internationalization and intercultural and local issues cannot be ignored in the goal of globalization for worldwide production and consumption. While intercultural issues of user interface design would refer to the religious, historical, linguistic, or aesthetic characteristics of a culture, localization in design might refer to the different requirements of specific local scales. To examine cultural effects on interface comprehension, Marcus and Gould (2000) applied Hofstede's (1980) five Cultural Dimensions in considering the usage requirements, preferences, metaphors, appearance, mental models and navigation of different user interface designs. However, the inherent concerns, expectations, values and perceptions that reflect cultural bias are difficult to uncover. The five dimensions are useful for inspiring a profound consideration of how to adapt design concepts for cultural diversity, but they are too conceptual and general to be of use in determining specific cultural characteristics that are relevant to actual design practice.

Following the essentiality of localization presented by Marcus, Yoe (1996) argues that extensive consideration should be given to cultural characteristics in creating user interface design. He presents the concept of CUI, or Cultural User Interface, which takes into consideration all the covert factors and elements of interface needs that are localized for particular cultures. Such factors as people's backgrounds, education levels and social habits determine the way that they interact with others and with environments. In one culture, there will be a shared understanding among people, resulting in their having similar attitudes, behaviors or reactions in specific circumstances. On the contrary, people's perceptions and customs will vary in the light of culture. Such differences could be reflected in the understanding and reception of the visual graphics, colors, functionality, information architecture and metaphors that are applied in user interface design. Hence, researchers and system developers need to comprehend accurately the shared knowledge of target groups in order to predict user perceptions and behaviors. By analyzing and comparing the differences in hobbies that strongly depend on culture, Yoe discusses the possibilities regarding differentiation and emphasis in interface design for several cultures. He addresses a simple principle for system development, that the functionality components and interface components of the application should be separated so that they can be replaced or tailored for different cultural requirements, and so that the system applications can be more easily adapted to conform to particular local characteristics (Yeo, 1996, 1998).

Okazaki and Rivas (2002) present the idea that consumers' online behavior might differ in relation to different cultural backgrounds and that such differences might be understood by applying content analysis of the web communication strategies of multinational companies. They argue that the online communication strategies of such companies, such as web-based advertising and promotional campaigns, lack standards with regard to matching different cultural contexts. In the cross-cultural comparison of web pages, they point out that there are three essential variables–information context, cultural values, and creative strategies–which seem unavoidably to be related to cultural contexts and to be factors that determine whether web pages can be accepted and accessed by target consumers. Because information content should reflect the extent of information requirements, webpage communication strategies should vary from country to country. In most social science findings, the social values of Western and Eastern cultures are quite diverse. Individualism, for example, is regarded as a main philosophy of the West, whereas, on the contrary, the Confucianism of the East seeks a stable and tight hierarchy in personal relationships. These inherent cultural differences directly determine users' motivations when it comes to online behavior and attitudes toward communication media and have a great impact on design strategies.

The Internet does break down the physical boundaries between different countries and cultures. But the users of online services, web pages related to commercial advertising, or communicating platforms, can be very different. To satisfy global users, these system and application developers need to take into consideration the cultural differences that emerge with regard to interface preferences, cognition and attitudes. In addition to the cultural shortcomings found in commercial applications, it is noticeable that design research processes and the evaluation of usability in past years have been lacking when it comes to the cultural aspects that are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Cultural Aspects of Design Research

The research mentioned above accentuates the importance of localization when aspiring to appeal to global users, and presents the cultural considerations of interface design. Marcus points out that interfaces could be designed with some thought given to cultural dimensions (Marcus & Gould, 2000). Yeo (1998), Okazaki and Rivas (2002), in their research, sort and analyze a variety of web pages to determine the cultural features of interfaces as further reference resources. However, these results are confined to users' external behaviors and preferences under the scope of economic interests. In the following, several discussions of the cultural aspects of design research and evaluation are introduced.

Barber and Badre (1998) address the term of “culturability.” They argue that usability tests for technology media need to include (or consider) cultural effects and to reflect the nuances of cultural context according to different target groups. In past years, “usability” was defined as how easy it was to learn and use a technology medium. With the growth of information science, the spread of applications usage has crossed national boundaries. Presently, system developers and designers find that there may be no design standards if users' cognition, which system information architecture rests on, is different in different cultures. Upbringing, education level, social attitudes and cultural background determine the way people perceive and interpret the world. In other words, cultural context does influence peoples' behaviors and usages when it comes to technology applications. Hence, Barber and Badre (1998) argue that interfaces, interactions, and media content not only all need to reflect the understanding of the cultures of target groups, but all of the design components of these media should be reconsidered with regard to cultural dimensions. They propose identifying all design elements that reflect localized features and then redefining them as cultural markers. With an understanding of the specific characteristics of target cultures, applying these cultural markers could improve the usability and efficiency of systems. In addition, similar to what Yoe (1998) argues in introducing his idea of CUIs, Barber and Badre (1998) believe that an awareness of apparent cultural markers could speed up the process of globalization.

Not only do usage requirements vary with different lifestyles and cultures, but users' attitudes, perceptions and cognition, and their purposes of usage also vary and also need to be tackled thoroughly for an understanding of an overall cultural context. Chau et al. (2002) suggest that apparent cultural differences emerge from consumers' online behavior, and that these reveal the inherent differences in users' attitudes toward technology between the East and the West. In their study, it was found that most Hong Kong subjects used Internet applications for the purposes of social contact, communication and maintaining personal relationships, whereas, on the contrary, the U.S. subjects used the Internet most commonly for the purpose of gaining information. Hence, they argue that the cultural contexts in which users function need to be taken into account so that their resulting behaviors can be better understood and predicted.

Considering the usability problems for multicultural users, Li et al. (2007) address the issues of culture-centered design based on the findings of psychological research on cultural differences. They claim that the main strategy of individualization or customization for encompassing a globalized market is merely to offer choices of different preference settings. They argue that this kind of limitation on interface design will mean the loss of some significant cultural values as well as a considerable loss in terms of quality. More than that, with the great progress being made in science and technology, human needs at a higher level of Maslow's hierarchy need to be fulfilled, such as emotional, social and cultural needs. Moreover, they also present some significant hazards in applying Western design principles and usability evaluation methods directly to Asia. Most traditional usability evaluation methods are not internationally practical and lack any consideration of distinctive national features. Hence, they argue that both design principles and usability test methods should be accommodated based on different cultures.

Cultural and Social Context in Design

In view of social requirements, Ackerman (2000) argues that there is a social-technical gap between what we know we must support socially and what we can support technically. Based on social science theories, he highlights that social activities are fluid and nuanced (Garfinkel, 1967; Strauss, 1993). People have a great ability to be aware of the details and nuances of social interactions, and their behaviors are strongly determined by situations (Goffman, 1959, 1971). People interact with others through many social cues, including those determined by facial expression, eye contact, gesture, tone of voice, and temperament. In common ground theory, it is suggested that people are constantly checking these social cues to make certain they are attaining mutual understanding. A shortage of social information will have a direct impact on communication (Sproull & Kiesler, 1986; Preece & Maloney-Krichmar, 2003). In addition, people determine their reactions and attitudes toward others according to such social nuances (Strauss, 1993). However, it is difficult to represent all of these social cues in computer-mediated communication. Sproull and Kiesler (1991) point out that online communicating is characterized by a lack of social context cues. The social order, social norms, social conscience and accountability of behavior that exist in the real world become uncertain and frail on the Internet.

By referring to the theories of social science, many studies have dealt with the importance of social concerns in technology developments (Donath, 2001; Agamanolis, 2003). Social issues are fundamentally related to cultural dimensions. It has been concluded that the core of social communication design is to attain to participants' shared understanding and to fulfill people's social needs in the real world. However, in different cultures, people's social activities, common understanding and needs are naturally not the same. In other words, the social issues emerging from interaction and interface design also represent the influence of cultural differences.

Since social context is one of the most important issues, understanding the culture that sustains a whole society is a must for interaction design. Most studies, whether of usability problems or commercial issues of localization, all reveal the importance of cultural effects by inductively analyzing and categorizing the interfaces of existing online applications that show usage bias. This usage bias is strongly related to culture or is a reflection of regionalism. There exist the concepts mentioned above, that is, the cultural markers and CUIs, that could help designers better understand users' cultural requirements with regard to interface use (Barber & Badre, 1998; Yeo, 1998). However, these studies do not take into account some issues, such as the nature of the media, and therefore the results can be applied only to redesigning or amending existing interfaces. In other words, methods such as inductively analyzing web pages could be used to sift through the diverse cultural preferences represented in these existing media, but it does not have the capacity for developing new interaction forms or for evaluating emerging technology. In addition, for a long while, the interfaces of communication media and online applications around the world have been influenced and determined by design guidelines and evaluation methods that have been developed, matured, and applied in Western countries. This means that a genre of web pages in a particular country might reflect multicultural characteristics and experiences, and might thus prove to be too complex to allow for recognizing the distinguishing features of a certain culture.

As social issues arise in science and technology development, cultural causes and effects have been discussed extensively in different fields and some researchers have tried to apply anthropology theories to the design process. However, these theories and findings sometimes range over many complex categories and are too detailed to translate into design guidelines. Nevertheless, the qualitative research methods of the social sciences, such as ethno-methodology and narrative inquiry or narrative research methods, are still essential for investigating the obscure connotations and inherent motivations behind users' behaviors, and for helping designers to comprehend cultural context.

Not only functionality and usability, but users' attitudes toward technology should be deliberated in the technology design process. In addition, people's behaviors, customs, motivations for usage and perceptions are all strongly influenced by their social and cultural context. To inspect whether the services and interactions provided by science and technology truly match users' social requirements, expectations and cultural contexts, it is necessary to examine what role emerging technologies might play and what effects they might have in different cultures. Thus, technologies can be developed so as to enrich and fulfill people's lives. In the next section, a new framework for design research will be presented as a way to investigate the essence of social interaction in a cultural context.

Tea Drinking - A Case Study of a Traditional Social Activity

In this study, it is argued that social activities are inherently embedded in a cultural context. A field study of one of Taiwan's traditional social activities is presented here to indentify the abundant cultural features which are involved in and influence people's social lives.

Tea drinking in Taiwan was once a striking local activity that was considered important for social contact and that represented a sense of leisure and affluence. It also connoted a particular philosophy of life, one that emphasized such qualities as propriety, refinement, and grace. However, tea drinking, like the conventional behaviors or traditional customs of most Asian countries, has been dramatically impacted by industrialization, urban modernization, globalization, and the widespread adoption of emerging technologies. In fact, along with the pursuit of these technologies, in particular those technologies that focus on social interactions, comes little consideration for social nuances or traditional values and characteristics.

This section presents a case study, which applies multiple user experience research methods to reveal different aspects of personal perceptions toward the overall cultural context of Taiwan's tea drinking customs. Five consolidated work models are constructed to present the details of the activities surrounding tea drinking, such as how people interact in various situations, and how technology affects the meaning of this traditional custom. In addition, the results of the in-depth interviews reveal significant cultural features behind such social activities. Based on the findings, an enhanced cultural model is proposed for both researchers and designers. This model illustrates a clear outline of the cultural effects acting upon people's real social activities.

Background

The cultures and local traditions of most Asian countries, including Taiwan, are now different from what they were in the past. Indeed, there exist many deeply inherent connotations and requirements behind the real social context. The aim of this study is to try to highlight the inherent and substantial values of traditional folkways so that they can be used to enhance both traditional customs and social technology design in the future.

In the past, traditional customs enhanced social interactions in various phases. People became acquainted with each other and cherished each other through social interactions and the conversations that occurred during these activities. People could easily make new friends, for example, or meet with old acquaintances while drinking tea. They found that the custom of tea drinking not only provided an all-around experience. They could enjoy the fresh taste, pleasant aroma, and mental alertness that the tea itself provided, and also, while drinking the tea, they could enjoy comparing their tea collections and practicing the artistry of making tea. Hence, the activity of tea drinking in Chinese society has always been thought of in relation to art and traditional conventions, as well as in relation to interpersonal relationships and social contact (Kumakura, 2002).

Two decades ago, tea drinking in Taiwan was a popular local activity involving social contact. It represented the leisure and prosperity of Taiwanese society. Middle-aged and elderly Taiwanese would share their tea time as a leisure activity at parks or temples where they were able to make new friends or chat with acquaintances while drinking tea. The Taiwan tea drinking tradition is an informal one, without many elaborate rituals on most occasions. It reflects a philosophy that seems to place value on refinement, personal relationships, and the interaction with one's surroundings (Wicentowski, 2000). Recently, with reports on the medical benefits of green tea, tea drinking has again become a popular and healthy activity attracting more people of different ages. The social functions of this custom create a cohesiveness in families and establish a habitual practice that can be passed on from one generation to the next. Furthermore, tea culture in Taiwan, by drawing on the local cultural heritage, also reflects a reaction against the influences of Western modernism. The cultural heritage of the tea sets and other artifacts and the physical environment of the tea drinking context are a way to display an old-fashioned, local aesthetic, and to declare a revival of local conventions.

Method

The main issues discussed in the research involve the overall context of tea drinking activities. Therefore, to reveal aspects in relation to both individual perceptions and to the overall activity context, this research applies multiple user experience research methods, which include practical observations and qualitative analysis through the use of contextual inquiries and in-depth interviews.

In order to distinguish the significant meanings of tea drinking for different generations, the three subjects chosen for the study were of different ages. The subjects were a retired senior citizen, a middle-aged parent, and a college freshman. Each had more than ten years of experience taking part in the Chinese tea drinking custom and each had made tea at least once a week in recent months.

In the case study, contextual inquiry (Holtzblatt & Jones, 1993; Kuniavsky, 2003), a field data-gathering technique based on anthropology and ethnography, was used to observe the entire process of tea drinking in the field, the social work flows and the real surroundings of the subjects.

As a design research method, contextual inquiry is prompt and efficient in practice. It gives researchers a clear framework to investigate an activity; for example, social interactions can be investigated by using the flow model and effects upon behaviors by using the cultural model. In addition, these models present a concise image for designers that allows them to understand the overall context and the problems that arise within that context. In addition, to attain a thorough understanding of the different generations' perspectives and attitudes toward Taiwan's tea drinking circumstances and customs, in-depth open interviews with the informants were also conducted. The research issues included the informants' purposes for tea drinking, their emotional perceptions and the special experiences that they had in relation to the environment or the tea drinking artifacts. Inquiries were also made into the meanings of others' participation in tea drinking activities and the particular impressions of others of tea drinking in order to reveal latent social interactions.

All the data derived in the previous studies were interpreted and decoded into an affinity diagram, and five consolidated work models–a flow model, a sequence model, an artifact model, a culture model, and a physical model–were also constructed to explore the problems and present the important design issues related to tea drinking activities (Beyer & Holtzblatt, 1998). By integrating the results of in-depth interviews and the five consolidated work models, an enhanced cultural model was developed and will be proposed in the next section.

Contextual Inquiry: Problems and Concerns

In the in-depth interviews and contextual inquiries, the findings regarding tea drinking activities can be separated into two sections. The first section is a discussion of problems and issues emerging from the tea drinking context based on the five consolidated work models of tea drinking. The second section offers a thorough presentation of the situation of today's tea drinking phenomenon in Taiwan.

In the contextual inquiries, significant findings were found for each case with regard to social communication, relationships, personal perspectives on tea drinking culture and the circumstances of tea drinking. The results also allowed for an overall understanding of tea drinking culture in Taiwan. The five consolidated work models were integrated as follows.

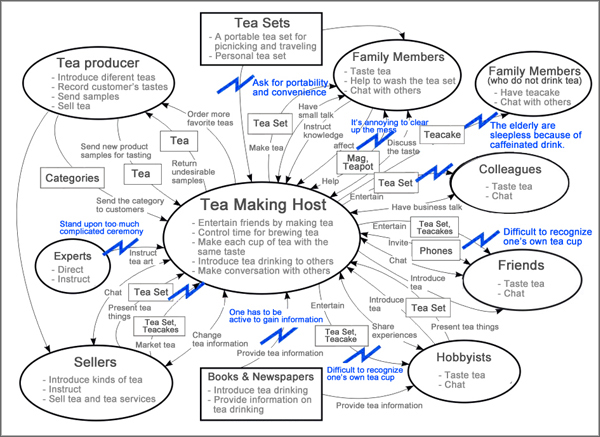

Consolidated Flow Model

As shown in Figure 1, the flow model presents how people's roles are identified and how they participate in a certain activity. The primary roles involved in the overall tea drinking activity include the tea server (the host), family members, colleagues, friends, hobbyists, tea sellers, the tea producer, and tea connoisseurs. The information keepers are defined as correlative books and newspapers, and the tea sets. The main assignments for family members are drinking tea, chatting with others, and livening things up.

Figure 1. Consolidated flow model.

In the flow model, the arrows explicate the communication between participants; the problems in such interactions are represented as a bolt symbol. What younger family members mostly dislike is that they are asked to do the washing and cleaning up after tea drinking. While drinking tea, the main problem for family members or their friends is difficulty in recognizing their own tea cup since the host has to repeatedly retrieve all of the cups to pour anew.

While drinking tea, friends, hobbyists, and tea sellers like to exchange various information and sentiments with the host about tea. Even though books and newspapers also contain much information about tea and tea drinking, the drawback is that what they provide is limited and somewhat useless in actual practice. However, most informants said that they would not consult about professional tea-related knowledge with tea sellers because of the pressure to purchase something from them or from tea connoisseurs because they might insist on undertaking a complicated tea drinking ceremony.

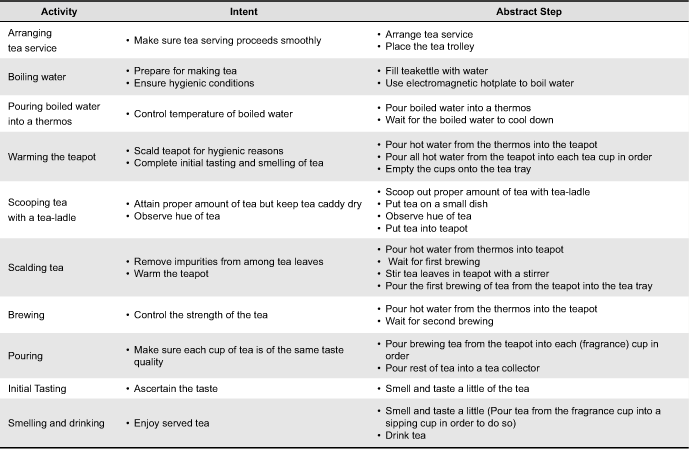

Consolidated Sequence Model

Table 1 shows the consolidated sequence model, which presents the typical process of tea drinking. The primary actions in serving and drinking tea are to arrange the tea service, boil the water, control the temperature of the hot water, warm the teapot, scoop the tea out of its container, scald the tea, brew and pour the tea, and do an initial taste of the tea. As shown in Table 2, most problems take place in the steps of controlling the temperature of the hot water and controlling the brewing time for the tea.

Table 1. Consolidated sequence model

Table 2. Problem breakdown using consolidated sequence model

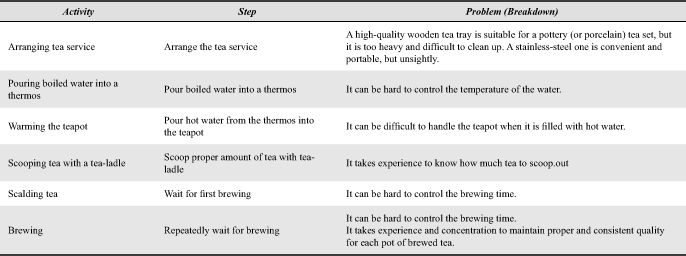

Consolidated Cultural Model

The cultural model manifests the concrete influences among participants' expectations, policies, and values. As shown in Figure 2, the arrows represent the directions of influence and how pervasive each influence is. The consolidated cultural model shows how traditional Chinese tea culture clearly affects some people's lifestyles in Taiwan. Spreading from the countryside to the city, the prevalent lao-ren-cha custom also is passed on from one generation to another (more details on this will be presented in the next section). People who are fond of tea drinking may inspire their friends or family members to form a tea drinking habit, and it is expected that more and more people will start becoming interested in this revival of tea drinking. Furthermore, there are influences that can make tea drinking attractive to people, such as the health benefits of green tea, the promotion of mental alertness that it offers and the physical relaxation of the tea drinking activity.

Figure 2. Consolidated cultural model.

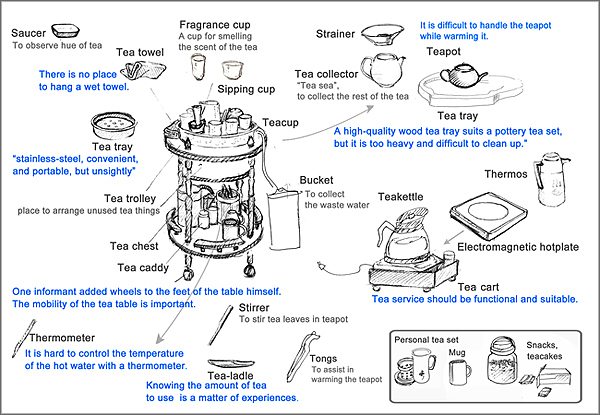

Consolidated Artifact Model

The artifacts used in an activity can reveal the experience of real events. Hence, the artifact model not only explains people's behaviors and usages but also implies their primary concerns. In Figure 3, the consolidated artifact model reveals that users' requirements and concerns are different from one another. One of the informants used a stainless-steel tea tray instead of a wooden one due to considerations of durability and convenience. In addition, he also attached wheels to the tea-table's legs for the sake of portability and ease of storage. In fact, most users make tea in their own manner, seldom following a formal tea art ceremony. As regards the tea service, tea drinkers are not generally too fastidious about the externals, but look for practicality, durability, and flexibility. Additionally, all of the informants indicated difficulties in controlling the time for brewing the tea and determining the proper strength of the tea, and expressed the belief that having experience is a must in tea making.

Figure 3. Consolidated artifact model.

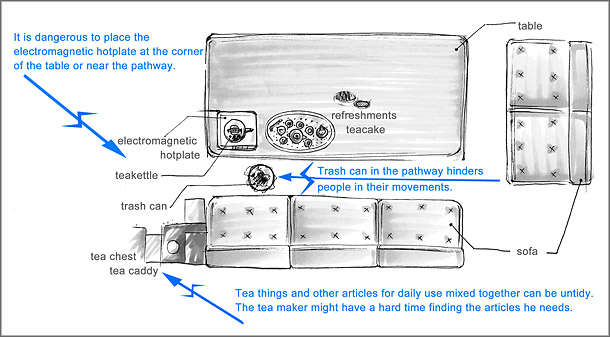

Consolidated Physical Model

The arrangement of an appropriate physical environment allows for the tea making activities to proceed smoothly, although most users seldom demand a well-equipped environment as a means to construct a cordial ambiance. However, as shown in Figure 4, problems can occur in the surroundings that can hinder the tea drinkers in their movements.

Figure 4. Consolidated physical model.

Today's Tea Drinking Phenomenon in Taiwan

The results of both the contextual inquiries and in-depth interviews were interpreted, analyzed, and categorized by a strict qualitative process. The main issues revealed in relation to tea drinking are ordered in an affinity diagram, and the results from the in-depth interviews are summarized in the following. At present, tea drinking gradually has become a widespread leisure activity among people of different ages in Taiwan. These tea drinking activities have also become a significant way to enhance the relationships within a family and to develop closer connections with the extended family.

Cultural Attitudes toward Tea Drinking

In China, the custom of tea drinking began about 2000 years ago. Due to its sweet and fresh taste, light aroma, thirst-quenching properties, and the fact that it can increase mental alertness, tea was the most common drink around the 8th century in China. Many tea houses were built for people to share tea, meet with friends, listen to music, or enjoy the natural beauty.

In the 1970s, tea drinking became a common form of healthy social relaxation in Taiwan. In the countryside, the elderly shared tea leisurely at parks or in the front of a temple, repeatedly pouring the brewed tea for each other from a small teapot into small porcelain cups, whiling away the whole afternoon. Their tea drinking often was a long drawn out and time-consuming affair. This particular way of making tea is called gong-fu-cha in Chinese, “tedious and time-consuming tea,” or lao-ren-cha, “tea of the old,” indicating something of the process involved and how old one has to be before he/she has enough time to make tea in this way (Wicentowski, 2000). In this period, tea drinking functioned as a promoter for good neighborhood relations.

Today, tea drinking is a significant and common practice in many people's daily lives. While having a meal, tea is also served for the purposes of social interaction and interpersonal concerns. Tea drinking in Taiwan is no longer an activity that concerns mainly the art of tea (such as the admiring, identifying, and nurturing of the teapot):

…Certainly we have some knowledge to master the temperature for brewing the tea, or to appraise the tea or the tea service. However, we are seldom fastidious about this… What we appreciate and love in tea sharing are the interactions among friends and family members, an enjoyable get-together, and a genial ambiance (quote from in-depth interview, translated from Chinese).

Tea drinking is such an important part of my daily life and one of my routine family activities…My parents are not particularly concerned about the brewing of the tea itself as I serve it to them. In my opinion, the purpose of tea drinking for my mother is to get the whole family together and make small talk to keep very close relationships among family members (quote from in-depth interview, translated from Chinese).

A codified method for brewing tea is not followed by most Taiwanese, and a lot of details are left out. When it comes to the tea service, people look for one that is functional, practical, and suitable instead of something that reflects the traditional genre of the art of tea. Because of rapid social change, people live at a fast pace today, and the meaning of having a cup of tea becomes quite different from what it was in the past. Tea drinking is a way to relieve stress and to enrich people's daily lives. Moreover, tea drinking also provides opportunities for social gatherings.

Social Interactions and Relationships

Tea drinking always goes along with other social activities. Various and frequent interactions are undertaken during the process of serving and sharing the tea. People's impressions of these interactions seem to be enhanced by taking place as part of the tea drinking activity. Tea drinking can serve to improve people's social relationships in three different aspects: it helps to expand one's personal social range, it helps to maintain social ties with friends or even coworkers, and it enhances the cohesion and identification among one's family members.

Many people enjoy entertaining their friends by making tea. If their brewing skills can gain their guests' praises, it is considered an honor for the host. For this reason, it is still traditional in Taiwan, and considered a kind of courtesy, to make new friends by introducing one's tea collection and through tea tasting. Therefore, this traditional custom can enhance people's social interactions in various phases. In this research, one informant said that it was much easier to successfully introduce his business or to make sales by offering a pot of his precious green tea.

Tea drinking also leads to more interactions among friends. The overall context becomes the catalyst to enhance such a situation. Many interactions between guests and hosts take place in the process of making, pouring, accepting, and tasting the tea. One can express one's concern for friends through conversation, slight gestures, or emotional expressions while drinking tea. These well-meaning actions also can make people more open-minded and enhance the friendliness of the social gathering.

Not only does it enhance social ties, but tea drinking also strengthens people's identification with their family members. In most cases, tea drinking is a way to show one's regard for one's family members. Due to rapid social change, people are struggling with the hustle and bustle of modern society and have thus begun to cherish any opportunity they have to spend time with family members. Tea drinking becomes a regular practice that can be passed on from one generation to the next. By looking at the different attitudes of the generations toward tea drinking in Taiwan, we can see that these reflect changes in the family from generation to generation. The older generation stands for the lao-ren-cha culture of a rich and fertile agricultural era, and the middle-aged and younger generations manifest the need to relax and escape from the anxieties of Taiwan's modernization.

…I can relax my mind by having tea and chatting with my parents. It's such a leisurely activity…As time passes, having tea with my family has become a routine activity. I can have some small talk with my family members…. It's quite different from other family activities. If you're just sitting next to your parents and watching television, you might have no conversation with each other. But we are always bound to have an intimate talk when we are sharing a pot of tea (Quote from in-depth interview, translated from Chinese).

Today, tea drinking plays different roles among people of different ages, and it does reflect the changes of social phenomena and values. This traditional custom is also enjoying a revival. Therefore, in terms of people's various requirements with regard to the essence of tea drinking, designers clearly have a chance to rethink and reform the tradition of tea drinking.

In conclusion, the overall activity of tea drinking and the subjects' perceptions of it are explored in this study. However, the five consolidated work models do not go far enough in pointing out the significant cultural dimensions of tea drinking, and do not present an easy way for designers to obtain practical knowledge and to translate it into design concepts. In the next section, an enhanced design model that takes into account cultural concerns is introduced.

An Enhanced Cultural Model for Social Activity

A brief introduction of tea drinking in Taiwan and many significant features and central values of this activity are discussed in this case study. Through observations of this traditional social activity the study provides several important cultural dimensions of the activity, and the consolidated work models illustrate the overall tea drinking context, including the workflow, the interactions among participants, the artifacts and the surrounding environment, as well as the potential problems that can occur during the course of the activity.

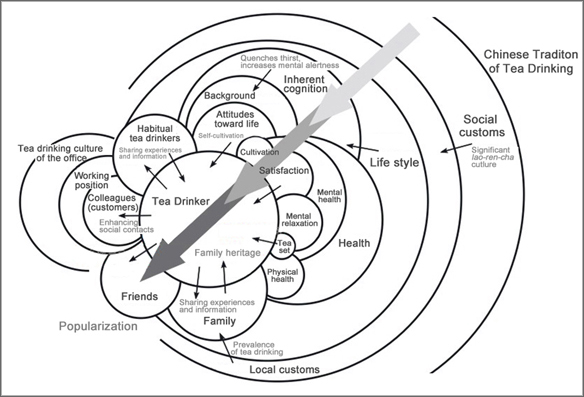

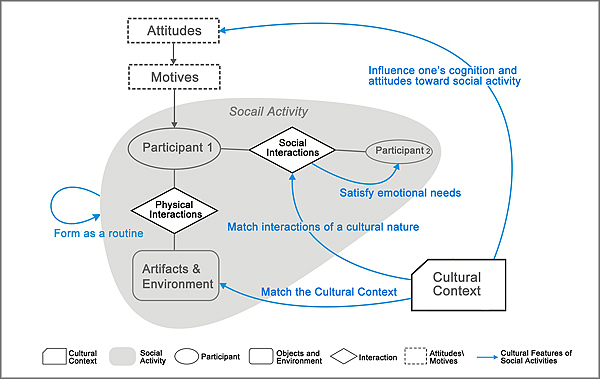

By making use of contextual inquiries, the cultural model shows the historical influences upon the activity and its participants. However, according to the results of in-depth interviews, a great deal of the qualitative concerns about cultural connotation are not well-represented by the cultural model. Such flows of influence are not clear enough for designers to figure out the exact cultural effects on a social activity, and these flows do not provide researchers a specific direction for examining the cultural dimensions involved in an activity. Integrating the findings of the case study and other cultural concerns addressed by Yeo (1996), Okayazaki and Rivas (2002), Chau et al. (2002) and Li et al. (2007), an enhanced model for cultural considerations in relation to social interactions is proposed in Figure 5.

Figure 5. An enhanced cultural model for social activity.

This model includes several components, with the key issue being how cultural context influences the overall social activity. Participant(s) indicates those involved in the activity, representing either a single person or a set of people with similar Motives and Attitudes toward the activity. The distinctions of different participants might be in relation to age, gender, behavior, and so on. Social Interaction represents interpersonal contact and communication, and Physical Interaction indicates people's actions upon the Artifacts (objects) and Environment of the activity.

As shown in Figure 5, it is considered that a social activity is triggered and influenced by participants' present motives and their permanent cognition and attitudes toward the activity. Hence, to comprehend a social behavior, it is a must to distinguish the participants' cultural background, as it might directly influence their viewpoints, attitudes, and values. The model also depicts the potential cultural effects on the social activity. Based on the qualitative case study of tea drinking, several cultural features that might influence participants' behaviors and the environment layout are addressed in more detail.

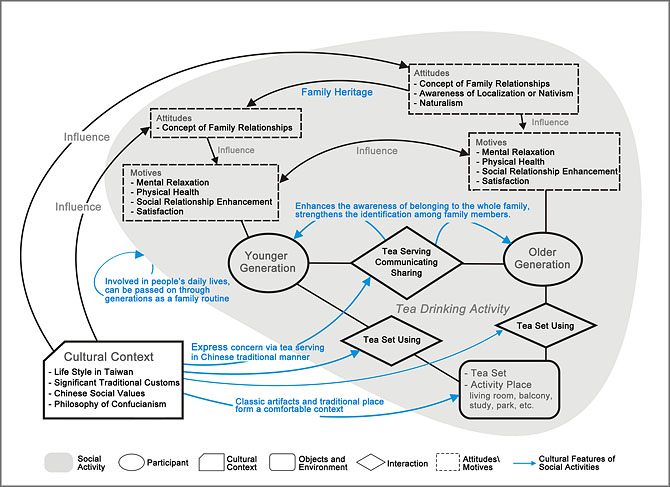

In Figure 6, the enhanced cultural model of tea drinking shows that the participants' motives and attitudes toward tea drinking are different among different generations and that such attitudes and actual behaviors are all strongly impacted by the cultural context.

Figure 6. An enhanced cultural model for tea drinking in context.

Perspectives of Participants

- Motives in the foreground: Both to maintain one's social relationships and to be in contact with one's intimates are the main purposes for most social activities. Moreover, these activities will be more attractive and valuable if they can also fulfill either people's mental or physical needs. With regard to mental needs, tea making, as a leisure activity, can help people to relieve the stress they have from work. In the view of physical needs, another factor that has made tea drinking popular is the medical reports related to tea drinking as a way to improve one's health. Hence, fulfilling people's needs in different ways could make social interaction design more attractive.

- Attitudes in the background: In addition to people's requirements and motivations, there will be some connotative reasons for people to engage in a social activity. These reasons might be invisible on the surface and difficult to inspect, but the influence truly exists for tea drinking to have been a custom for such a long period of time. For instance, informants' attitudes toward tea drinking potentially reflect the nature of their awareness of Chinese culture and of localization. To have a complete understanding of such a social activity, it is necessary to trace people's perspectives from a historical and cultural dimension.

Features of a Social Activity

- Matches the cultural context: A cordial, intimate and culturally oriented environment can pave the way for natural social interactions. As shown in the study, the traditional style of Chinese architecture and artifacts forms a scenario for a comfortable social gathering. In social interaction design, it might be an advantage to provide potential users with a cultural environment that contains familiar objects.

- Supports interactions of a cultural nature: In Chinese culture, serving is an extremely important means of expression representing one's attitudes toward others. While drinking tea, it is quite obvious that one would simply show his/ her concern and respect toward others via the pouring of a cup of tea. This kind of action seems unavailable in today's computer-supported platforms, and therefore is not a design concept of concern yet. However, a social software design must match not only local customs and practices but must also support interactions of a cultural nature.

- Satisfies emotional social needs: Another important significance of social activities is that they must meet people's emotional needs and also help maintain their social ties. In the case of this study, tea drinking not only enhances an awareness of belonging to a whole family but also strengthens self-identity among family members. Such social needs might have to be met in a way distinct from the way they might be met in different communities or different cultures.

- Allows for the formation of a habit or routine activity: Traditional social activities, as the term implies, are long lasting. The reasons for such permanence might be that these activities are a part of people's daily lives and were formed in a cultural context. For instance, tea drinking has been continually passed on through generations in many families and, now, has also become much more popular due to a belief in the health benefits of green tea. Hence, to achieve computer-supported social software success, an important strategy would be to find a way to make this social activity an important part of people's lives.

By means of this enhanced cultural model, the cultural context of an activity such as tea drinking can be revealed. Designers can get a better understanding of the comprehensive perspectives of participants, including their life styles, internal requirements and significant cultural values related to local customs, and also can better understand the features of a social activity within its cultural context.

Design Implications

In this research, several user experience study methods are combined with the social science qualitative process and analysis techniques. Based on the findings from examining tea drinking customs in Taiwan, the implications for future technologies were delivered in the form of a workshop with real users and experts from different disciplines.

Participatory Design Workshop

In participatory design, a co-design (Sanders, 2000; Westerlund, Lindquist, Mackay, & Sundblad, 2003) workshop is held with prior interviewees and many researchers from different disciplines, including industrial design, computer science, information engineering, and civil engineering, to find out the specific problems in a field and to devise reasonable and meaningful design ideas from the input of these different field experts. If an artifact is meaningful, this will be determined by its frequent usage, by its fitting into the existing environment, or by other memorable perceptions. Hence, it is crucial to gain opinions from users and experts together, and then to conduct a simulation in a real setting to discover users' needs and desires.

The affinity diagram and work models were rendered to delineate the different phases of tea drinking. All of the participants of the workshop brainstormed for hours to explore appropriate solutions for enhancing tea drinking activities and to develop new design concepts for different purposes or to meet users' requirements (Buchenau & Fulton Suri, 2000; Oulasvirta, 2004).

Design Implications

The findings of research on cultural activities indicate the importance of inner values and the expectations of interpersonal relationships. For the design of technology applications in the future, the design implications suggested in this paper include three dimensions: technology implications for general social interactions in a cultural context; technology implications with regard to cultural inheritance; and the design for the case study – the facilitation of tea serving. The main aspects of the design implications are as follows:

Enhancement of Social Interactions in a Cultural Context

The concepts of filial piety, courtesy, and respect are at the core of traditional Asian social relationships, and in fact, such cultural values are embedded in traditional customs. For this reason, it is important to identify the cultural context and values attached to it in order to develop an application to enhance the social interactions for a certain group.

- Extending cultural manners: For instance, the act of serving tea represents a way to express one's concern for others, and, in this light, it serves as a means for younger people to show their reverence for their elders. However, web-based social interactions do not provide actions that allow people to express such kinds of subtle feelings. With the idea of extending Chinese manners, social software might provide an interaction model through which people could make some additional efforts to show their respect for others.

- Providing a host to run the social activity: In a real social context, there must be a host to look after all participants and to conduct the overall activity proceedings. Such a model is extremely important to ensure the success of a social activity. Many studies of online communities have emphasized that the role of a manager is necessary in groupware. Here, it is proposed that such a host model should be applied in each single social activity event held on computer-mediated applications.

- Reproducing existing social customs: In Chinese society, the subtle hierarchy of a family provides an important way to maintain the interactions that take place within a family circle. In the case study, tea drinking itself acts as a catalyst in gathering people together, and creates an atmosphere that encourages people to talk and open up in a natural and pleasant way. However, with most communicating applications it is very difficult to engage different generations at the same time, such as the different generations that exist within a large family, or make use of these applications over a long period of time. To reproduce existing traditional customs that originally involve many participants would be one approach for online software to engage more target users.

- Enhancing memories: In the future, what technology could do to improve would be to offer a way to preserve traditional social activities as unfading memories. Here, we suggest that memorable interactions and joyful experiences might be recorded by some innovative design or multimedia technique that contained more subtle expressions than a picture does in a photo album. In addition, for family members who live at a distance, a proper application of multimedia or information technology that could capture such a traditional social activity might help them to maintain intimate interactions with their family, and also serve as a means to convey their concerns and respect for family members.

Cultural Inheritance

In further design research, it is of great importance to explore ways to extract different significant qualities from different cultures as well as to develop designs that match how people live their lives. Cultural tradition could be maintained by finding ways to help cultural activities to continue. The connotative virtues and the richness of a culture could also be experienced and enhanced through new technology.

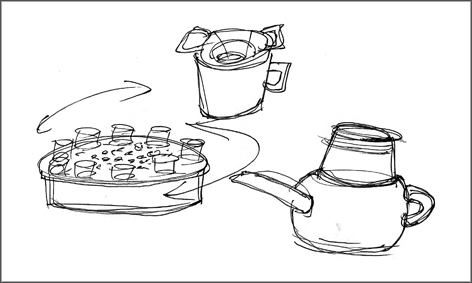

- Applications of traditional cultural metaphors: To keep traditional customs fascinating and popular, additional cultural metaphors could be added in order to vary the overall context of the tradition and thereby make it more enjoyable. As shown in Figure 7, a rotatable tea tray inspired by the lazy Susan could offer the host a fun and convenient way of pouring brewed tea into all of the cups, and as a way to serve people snacks such as teacakes without anyone having to get up from their chair or to reach over someone else.

- Enhancement of inherent cultural values with awareness and meaning: In the case of tea drinking research, the Internet and communicating media provide a world of related information to direct the uninitiated to approach the art of tea, and to present the medical benefits of green tea. However, such information is somewhat irrelevant to people's daily lives. To ensure that culture is passed on, it is a must to apply the essential meaning of traditions for enhancement.

Figure 7. A rotatable tea tray.

Facilitation of Tea Service

- Simplicity of tea making process: The main problems revealed in the research are that the artifacts used in making tea are too numerous to handle and that the process of serving the tea requires a high degree of concentration and also experience. It should be a top priority in redesign to simplify the tea sets or to reduce the complexity of the tea making process without losing the essence of the tradition.

- Wizard (guidance strategy and information): For the tea making process to be successful, the ideas of tangible design (Ranson et al., 1996; Mazalek, Davenport, & Ishii, 2002; Djajadiningrat, Wensveen, Frens, & Overbeek, 2004) or intuitive usage (Hara, 2004) might be a chief consideration in redesigning a tea set. In addition, technology is useful for providing users with adequate information, such as the temperature of the water and the strength of the tea, so that they can better handle the entire tea making process.

- Mobility, durability, and portability: People's requirements have changed. They are not very particular about the external appearance of the teapot, but value the functionality it might offer. In addition, tea drinking does not always take place in the same location. It might occur in a living room, a study, or an open-air garden. Hence, a portable and serviceable tea set is more appropriate than a traditional wooden one.

As these redesign suggestions reveal, applying cultural qualities to design concepts could make something that is common become friendlier and more desirable. The design of computer-mediated communication and social interactions, or the interface of localization, might follow the same considerations as a way to match people's inherent needs.

Conclusion

In this research, it is argued that social behaviors are deeply localized and historical on the account of cultural background. In the case of tea drinking in Taiwan, this activity performs a social function by creating cohesiveness in families and by offering a habitual practice that can be passed on from one generation to another. Tea drinking improves people's social relationships in three different aspects: it expends their personal social range, helps them to maintain their social ties, and enhances the cohesion and identification of the family. Through this field study of a traditional social activity, subtle interactions and cultural nuances are revealed, and it can be seen that most social software designs seem to fall short when it comes to cultural concerns.

In addition, based on the observations and interpretations made in the case study of tea drinking in Taiwan, an enhanced cultural model of social interaction design for further technology development is proposed. There are three important parts of the model that help to identify the relation between the social activity and its cultural context. First, the cultural context that sustains the overall activity has to be distinguished. Second, to develop a thorough understanding of the target users, both their foreground perceptions and cultural attitude backgrounds have to be taken into account. Finally, several significant dimensions of the social activity itself need to be carefully calculated in design development. In this way, the design could be examined to determine whether it matches the original cultural context and provides appropriate ways of interacting, or whether it fulfills people's needs and can naturally be a part of people's daily lives.

The enhanced work model was proposed according to the results of a case study in Taiwan, which has its own traditional social culture. This model can be extended by obtaining more cultural features via further research. In conclusion, we hope this research can encourage more attention to cultural concerns in technology development. Since it is culture that sustains a whole society, it should be a primary consideration in interaction design.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the informants and those who participated in this research, shared their experiences, and offered excellent opinions on the design issues.

References

- Ackerman, M. (2000). The intellectual challenge of CSCW: The gap between social requirements and technical feasibility. Human-Computer Interaction, 15(2-3), 179-203.

- Agamanolis, S. (2003). Designing displays for human connectedness. In K. O'Hara, M. Perry, E. Churchill & Russell, D. (Eds.), Public and situated displays: Social and interactional aspects of shared display technologies (pp. 309-334). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Barber, W., & Badre, A. (1998). Culturability: The merging of culture and usability. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Human Factors and the Web. Retrieved December 20, 2007, from http://zing.ncsl.nist.gov/hfweb/att4/proceedings/barber/

- Beyer, H., & Holtzblatt, K. (1998). Contextual design: Defining customer-centered systems. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

- Bourges-Waldegg, P., & Scrivener, S. A. R. (1998). Meaning, the central issue in cross-cultural HCI design. Interacting with Computers, 9(3), 287-309.

- Buchenau, M., & Fulton Suri, J. (2000) Experience prototyping. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques (pp. 424-433). New York: ACM.

- Chau, P. Y. K., Cole, M., Massey, A. P., Montoya-Weiss, M., & O'Keefe, R. M. (2002). Cultural differences in the online behavior of consumers. Communications of the ACM, 45(10), 138-43.

- Choi, B., Lee, I., Kim, J., & Jeon, Y. (2005). A qualitative cross-national study of cultural influences on mobile data service design. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 661-370). New York: ACM.

- Clemmensen, T., Shi, Q., Kumar, J., Li, H., Sun, X., & Yammiyavar P. (2007). Cultural usability tests – How usability tests are not the same all over the world. In Proceedings of the 12th Conference of Human Computer Interaction: Usability and Internationalization (pp.281-290). Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- Djajadiningrat, T., Wensveen, S., Frens, J., & Overbeek, K. (2004). Tangible products: Redressing the balance between appearance and action. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 8(5), 294-309.

- Donath, J. (2001). Mediated faces. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Cognitive Technology: Instruments of Mind (pp. 373-390). London: Springer-Verlag.

- Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Anchor-Doubleday.

- Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in public. New York: Basic Books.

- Greenberg, S., & Marwood, D. (1994). Real-time groupware as a distributed system: Concurrency control and its effect on the interface. In Proceedings of the 1994 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 207-217). New York: ACM.

- Grudin, J. & Palen, L. (1995). Why groupware applications succeed: Discretion or mandate? In H. Marmolin, Y. Sundblad, & K. Schmidt (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 263-278). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Gudykunst, W. B., & Ting-Toomey, S. (1988). Culture and interpersonal communication. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Hara, K. (2005). Design of design (Y. Huang, Trans.). Taipei: Pan Zhu Creative. (Original work published 2003).

- Herman, L. (1996). Towards effective usability evaluation in Asia: Cross-cultural differences. In Proceedings of the 6th Australian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction (pp. 135-136). Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society.

- Herring, S., Scheidt, L. A., Bonus, S., & Wright, E. (2004). Bridging the gap: A genre analysis of weblogs. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (Track 4, Vol. 4, p. 40101.2). Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's consequences, international differences in work-related values. Berverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Holtzblatt, K., & Jones, S. (1993). Contextual inquiry: A participatory technique for system design. In Schuler, D. & Namioka, A. (Eds.), Participatory design: Principles and practices (pp. 177-210). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Honold, P. (2000). Culture and context: An empirical study for the development of a framework for the elicitation of cultural influence in product usage. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 12(3-4), 327-345.

- Hughes, J. A., Randall, D., & Shapiro, D. (1993). From ethnographic record to system design: Some experiences from the field. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 1(3), 123-142.

- Hutchinson, H., Mackay, W., Westerlund, B., Bederson, B., Druin, A., Plaisant, C., et al. (2003). Technology probes: Inspiring design for and with families. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 17-24). New York: ACM Press.

- Ji, L., Peng, K., & Nisbett, R. E. (2000). Culture, control, and perception of relationships in the environment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 943-955.

- Kensing, F., & Blomberg, J. (1998). Participatory design: Issues and concerns. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 7(3-4), 167-185.

- Kumakura, I. (2002). Tea drinking culture in the world. Foods & Food Ingred J Jpn, 204, 60-76.

- Kumar, R., Novak, J., Raghavan, P., & Tomkins, A. (2004). Structure and evolution of blogspace. Communications of the ACM, 47(12), 35-39.

- Kuniavsky, M. (2003). Observing the user experience: A practitioner's guide to user research. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Li, H., Sun, X., & Zhang, K. (2007). Culture-centered design: Cultural factors in interface usability and usability tests. In Proceedings of IEEE Societie's ACIS International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking, and Parallel/Distribute Computing (pp. 1084-1088). Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society.

- Marcus, A. (1993). Human communication issues in advanced UIs. Communications of the ACM, 36(4), 100-109.

- Marcus, A. (2002). Global and intercultural user-interface design. In J. A. Jacko & A. Sears (Eds.), The human-computer interaction handbook: Fundamentals, evolving technologies and emerging applications (pp. 441-462). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Marcus, A., & Gould, E. W. (2000). Crosscurrents: Cultural dimensions and global Web user-interface design. Interactions, 7(4), 32-46.

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224-253.

- Mazalek, A., Davenport, G., & Ishii, H. (2002). Tangible viewpoints: Physical navigation through interactive stories. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (pp. 153-160). New York: ACM.

- Nardi, B. A., Schiano, D. J., & Gumbrecht, M. (2004). Blogging as social activity, or, would you let 900 million people read your diary? In Proceedings of the 2004 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 222-231). New York: ACM.

- Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108(2), 291–310.

- Okayazaki, S., & Rivas, J. A. (2002). A content analysis of multinationals' Web communication strategies: Cross-cultural research framework and pre-testing. Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, 12(5), 380-390.

- Preece, J., & Maloney-Krichmar, D. (2003). Online communities: Focusing on sociability and usability. In J. A. Jacko & A. Sears (Eds.), The human-computer interaction handbook: Fundamentals, evolving technologies and emerging applications (pp. 596-620). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Ranson, D. S., Patterson E. S., Kidwell D. L., Renner, G. A., Matthews, M. L., Corban, J. M., et al. (1996). Rapid scout: Bridging the gulf between physical and virtual environments. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 442-449). New York: ACM.

- Ratner, C. (1997). In defense of activity theory. Culture and Psychology, 3(2), 211–223.

- Sanders, E. B-N. (2000). Generative tools for co-designing. In S. A. R. Scrivener, L. J. Ball, & A. Woodcock (Eds.), Proceedings of CoDesigning 2000 Conference (pp. 3-12). London: Springer-Verlag.

- Searle, J. R. (1995). The construction of social reality. London: Penguin.

- Shore, B. (1996). Culture in mind: Cognition, culture, and the problem of meaning. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1986). Reducing social context cues: Electronic mail in organizational communication. Management Science, 32(11), 1492-1512.

- Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1991). Connections: New ways of working in the networked organization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Strauss, L. (1993). Continual permutations of action. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Strøm, G. (2006). Interaction design for countries with a traditional culture: A comparative study of income levels and cultural values. In T. McEwan, J. Gulliksen, & D. Benyon (Eds.), People and Computers XIX - The Bigger Picture (pp. 301-316), London: Springer.

- Wellman, B., & Hampton, K. (1999). Living networked on and offline. Contemporary Sociology, 28(6), 648-654.

- Westerlund, B., Lindquist, K., Mackay, W., & Sundblad, Y. (2003). Co-design methods for designing with and for families. In Proceedings of the 5th European Academy of Design Conference. Barcelona: Techne.

- Wicentowski., J. (2000). Narrating the native: Mapping the tea art houses of Taipei. Paper presented at the 5th Annual Conference on the History and Culture of Taiwan, Los Angeles, CA. Retrieved July 5, 2007, http://www.international.ucla.edu/cira/paper/TW_Wicentowski.pdf

- Yeo, A. (1996). CHI: Cultural user interfaces: A silver lining in cultural university. ACM SIGCHI Bulletin, 28(3), 4-7.

- Yeo. A. (1998). Cultural effects in usability assessment. In CHI 98 Conference Summary on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 74-75). New York: ACM.