User Value:

Competing Theories and Models

Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey

In design research, the issues of what exactly constitutes user value and how design can contribute to its creation are not commonly discussed. This paper provides a critical overview of the theories of value used in anthropology, sociology, philosophy, business, and economics. In doing so, it reviews a range of theoretical and empirical studies, with particular emphasis on their position on product, user, and designer in the process of value creation. The paper first looks at the similarities and differences among definitions of value as exchange, sign, and experience. It then reviews types and properties of user value such as its multidimensionality, its contextuality, its interactivity, and the stages of user experience dependency identified by empirical studies. Methodological approaches to user value research and their possible applications in design are also discussed. Finally, directions for future research on user value are discussed giving particular emphasis to the need of tools and methods to support design practice.

Keywords – Consumer Value, User Value, User-Centered Design.

Relevance to Design Practice – The critical overview of the notion of value presented in this paper would be of interest to designers adopting a user-centered approach, as it could guide their efforts to better understand users and deliver products which are of value to them.

Citation: Boztepe, S. (2007). User value: Competing theories and models. International Journal of Design, 1(2), 55-63.

Received January 23, 2007; Accepted June 9, 2007; Published August 1, 2007.

Copyright: © 2007 Boztepe. Copyright for this article is retained by the author, with first publication rights granted to International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

Corresponding Author: boztepe@id.iit.edu

Introduction

The concept of user-centered design has arguably given rise to one of the most fundamental changes in the field of design over the past few decades (Fulton Suri, 2003; Melican, 2004). Design has since shifted focus from giving form to objects and information to enabling user experiences, and from physical and cognitive human factors to the emotional, social, and cultural contexts in which products and communications take place (Heskett, 2002a; Margolin, 1997; Redstrom, 2006). This shift has been supported by business strategies aiming for sustainable competitive advantage. Today, there is a growing recognition that providing superior value for users is instrumental for business success (Cagan & Vogel, 2002; Kim & Mauborgne, 2005; Vandermerwe, 2000). Kim and Mauborgne (2005), for example, argue that focusing on creating advances in customer value can make competition irrelevant by opening up entirely new markets. In their investigation of what it takes to create breakthrough products, Cagan and Vogel (2002) conclude that one of the key attributes that distinguishes breakthrough products from their closest followers is the significant value they provide for users. After all, as Drucker (2001) has pointed out, "customers pay only for what is of use to them and gives them value" (p.172). In current research, however, the notion of user value still remains largely unexplored. For one thing, there is no established theory of value that can guide design. This paper is thus an attempt to provide a critical overview of the competing theories and models most prevalent in the study of user value. The paper first reviews definitional issues regarding user value in economics, sociology, anthropology, and business research. Next, similarities and differences among definitions of value as exchange, value as sign, and value as experience are discussed. Comparison among different theories is also made in terms of their perspective on what the source of user value is. The paper then reviews types and properties of user value identified by empirical studies. Design's role in creation of value is also discussed. Methodological approaches to user value research and their possible applications in design are then examined. Finally, directions for future research on user value are discussed, giving particular emphasis to the need of tools and methods to support design practice.

Definitional Issues

As with many aspects of design, the field is plagued by terminological confusion regarding the use of the term value. Part of the confusion comes from the fact that value is a highly polysemous word. Its meaning oscillates between concepts as distant as economic return and moral standards. For example, there is a general belief among designers that design can add value by the fact that it can be used to devise products with increased value and which embody moral values (Heskett, 2002c). Lack of consensus on the use of the term value, nevertheless, is not unique to the field of design. It spans a number of disciplines, including economics, sociology, anthropology, psychology and marketing. Within this spectrum, Graeber (2001) identifies the main approaches to the definition of value: (1) the notion of values as conception(s) of what is ultimately good in human life, (2) in an economic and business sense, value as a person's willingness to pay the price of a good in terms of cash in return for certain product benefits, (3) value as meaning and meaningful difference, and (4) value as action. Leaving aside the use of the term in its plural form, which stands for enduring beliefs or for what is ultimately good and desirable in life (Rokeach, 1973), the focus here will primarily be on terms such as consumer value or customer value, where value refers to the evaluation of some object/product by some subject/user. This focus seems to offer a relevant ground for discussion of value in design, as it promises to examine the concept of value within the user-product relationship.

Value as Exchange and Use

Reviewing some of the definitions of consumer value reveals that they are firmly placed within the economic paradigm, where value is defined in terms of the monetary sacrifice people are willing to make for a product (e.g., Butz & Goodstein, 1996; Gale, 1994; Zeithaml, 1988). The emphasis is on the point of exchange, and money is seen as a fundamental index of value. The assumption is that, at the moment of purchase, people make a rational evaluation and calculation of what is given versus what is taken in terms of money for product quality. Such a view may be problematic for design as it overlooks the situation of use. In a study on the assignment of value to fruit beverages, Zeithaml (1988) points out that use-related, non-monetary issues such as time and effort spent on the preparation of the beverage were important in users' assessments of product value, and concludes that these issues should be acknowledged as well. Also, for communication products, such as websites, there is no purchase stage or evaluation of choices on the spot as there is with physical products. In other words, the-money-spent-for-product-quality view of value seems to exclude a range of communication products.

Marxist theory provides a useful distinction here. It conceives of value as having a dual nature—made up of use value and exchange value (Marx, 1990). Independent of labor, use value relates to the utility of the physical properties of a product, which is realized only upon its use. Although Marx does not further develop his theory of use value, he puts forward the idea that value is conditioned by the physical properties of products.

The question of what is the source of value, however, constitutes one of the major disagreements among different theories. Is it something subjectively assigned by the user and independent of the product's physical qualities? Or, is it something embedded in the object and recognized by the user? These questions have been among the central issues of the branch of philosophy concerned with the theory of value, known as axiology (Frondizi, 1971). In axiological theory, a bipolar distinction exists between objectivists and subjectivists. Positioning value as inherent in the object, as Marx claims, and existing before a subject interacts with or evaluates it, is a firmly objectivist view. It resonates well with Levitt's (1981) definition of product as "a promise, a cluster of value expectations" (p. 94). According to Porter's (1985) value chain, value is gradually added through the different stages of product development, manufacturing, and distribution. In other words, value is something that the producer puts into the product. Giving no account for the capability of users to imbue objects with meaning and value, such objectivist approaches are viewed as nothing but easily refutable (Frondizi, 1971; Holbrook, 1999).

It is easy to refute this approach, for example, by recognizing that there is a range of goods such as gifts, memorabilia, photos and spiritual objects which are not necessarily utilitarian, nor do they circulate in the market. These goods do not have a monetary price attached to them, but they are considered to be of high value by the people who possess them (Belk, 1987; Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton, 1981). The theory of value as exchange or value as use thus seems to fall short in explaining the high value of this group of objects for their owners.

Value as Sign

Anthropological and sociological theories, on the other hand, emphasize the social and cultural aspects of value. This includes taking into account the symbolic meanings that can be attributed to goods. Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton's (1981) study, for example, illustrates that the most valued domestic objects are valued primarily because of the symbolic meanings attached to them. People have an enormous capacity and tendency to invest objects with meanings that sometimes have nothing to do with their utility or with the meanings intended by their producers. They often value objects not for what they do, or what they are made of, but for what they signify. In Veblen's (2001) conceptualization of conspicuous consumption, for example, goods are valued because they serve as an index of social status. And Baudrillard (1968/2006, 1970/1998) treats consumption as a way in which people converse with each other. This conversation involves a code shared by the members of a society, and the products act as signs communicating certain messages and images which are independent of their use. Their value is therefore a sign value, which displaces use value and exchange value. For example, it is quite common for people in the so-called developing countries to acquire Western goods not only for their utility but because of their imposed association with modernity and the lifestyles of their originators (Ger & Belk, 1996). An example of such consumption may be found among the Muria Gonds, where "the richer fishermen were spending their excess earnings to purchase unusable television sets [having no access to electricity], to build 'garages' onto houses to which no automobiles had access, and to install rooftop cisterns into which water never flows" (Gell, 1986, p. 114). Bourdieu (1979/1984) views such interaction with goods as a means of accumulating capital, mainly of a symbolic (i.e., in relation to the honor and prestige accumulated through one's practices) and social (e.g., in relation to one's own network of interpersonal relations) nature. This notion of value, then, calls for consideration not only of the use of products and communications but also of how they are made sense of and what the range of social ends they provide to users are, including ends involving issues of status, prestige, and identity.

From the standpoint of the source of value, a value-as-sign approach posits that value emerges through the subjective experience of the user, and thus, objects cannot contain value. Value does not necessarily reside in an object's tangible materiality, but rather in the message it communicates. As in semiotics, physical form enables communication, but does not construct meaning, and therefore cannot be a source of value. It is the symbol systems which are known and shared in a society that construct value. Disregarding a product's capacity to shape meaning and users' experiences, this view is as easily refutable as the objectivist one. After all, designers create and alter forms with the purpose of modifying meaning and creating value.

Value as Experience

It is clear that in relating value to design, it is difficult to adopt any of the definitions reviewed so far. As Graeber (2001) has pointed out, each definition poses problems due to its lack of sufficient consideration of the other definitions. Heskett (2002b) also has noted that it is often difficult to talk about the utility/use or significance/meaning of an object or communication separately because, in practice, they are closely interwoven. It is equally difficult to argue that value resides in an object's materiality or in a symbol system alone. Frondizi (1971) advocates an intermediate position where value is created at the interface of the product and the user. As Holbrook (1999) puts it, "value resides not in the product purchased, not in the brand chosen, not in the object possessed, but rather in the consumption experience(s) derived therefrom" (p. 8). Such a perspective of value as experience, where a product's value pertains to the experiences associated with that product, offers the potential for reconciling the different approaches offered so far.

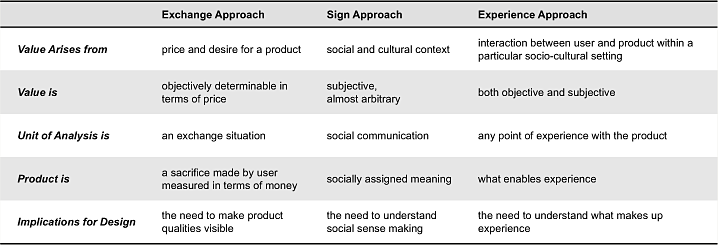

This perspective does not, nevertheless, provide an exclusive alternative to other definitions, but rather, it encompasses many aspects of them (Table 1). At its core is the premise that what people actually desire is not products, but the experiences products provide (Pine & Gilmore, 1999). As Cagan and Vogel (2002) point out, "[s]ince products enable an experience for the user, the better the experience, the greater the value of the product to the consumer" (p. 62). Amazon.com, for instance, is valued for the superior shopping and browsing experience it provides, and OXO Good Grips products for the easy and comfortable food preparation experience that they provide.

Experiences emerge from interaction between the product and the user. Any user activity involving a product is an engagement in experience with that product. However, it should be noted that, although activities are central to the concept of experience, they are not equal to it. Dewey (1966) writes:

The nature of experience can be understood only by noting that it includes an active and passive element peculiarly combined. On the active hand, experience is 'trying'--a meaning which is made explicit in the connected term experiment. On the passive side it is 'undergoing'. When we experience something we act upon it, we do something with it; then we suffer or undergo the consequences. We do something to the thing and it does something to us in return. Mere activity does not constitute experience. It is dispersive, centrifugal, dissipating. (p. 146)

Activity usually consists of a series of actions oriented towards a specific goal (Leont'ev, 1978). Experience, on the other hand, involves the additional dimension of reflecting upon the consequences of one's activities. As Margolin (2002) puts it, experience has both operative and reflective dimensions. "The operative dimension refers to the way we make use of products for our activities. The reflective dimension addresses the way we think about a product and give it meaning" (p. 42). In other words, experiences with products relate not only to the activities but also to the meanings they add to people's lives, such as the symbolic meanings described in Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton's (1981) study. Therefore, the notion of value as experience encompasses aspects of both utility and social significance consequences created through interaction with products. User experience involves the juxtaposition of (1) user context and characteristics, and (2) whatever features the product brings to the interaction, including both formal and functional characteristics. Users interact with products within the context of their goals, needs, cultural expectations, physical context, and emotions. And products, with their tangible and intangible qualities, can influence the way users interact with them. What we call user value is thus created as a result of the interaction between what the product provides and what the users bring in terms of their goals, needs, limitations, etc.

Yet, the definition of value as experience is not without problems. For one thing, it attempts to define such an elusive term as value with another similarly elusive one. Despite its centrality to design theory and practice, the knowledge of what constitutes user experience and how to understand and enhance it is yet in its babbling stage. It is necessary that the discussion of value in design be developed in sync with a discussion on user experience.

Table 1. An Overview of the Definitional Approaches to User Value

Properties of User Value

Relative and Contextual

If value is closely tied with experience, then it carries some of the properties of experience. According to Dewey (1938), experience is not something that is totally internal to the individual, but instead, "an experience is always what it is because of a transaction taking place between an individual and what, at the time, constitutes his environment" (p. 43). Experiences are context- and situation-specific; that is, they change from one set of immediate circumstances, time, and location to another. In a similar way, value changes as cultural values and norms, and external contextual factors, change (Overby, Woodruff, & Gardial, 2005). Consider the example of owning an automobile. Having a car in a small U.S. town increases accessibility to different places, such as shopping malls, sites of interest, etc. However, the same car in a metropolitan city like New York, where parking space is virtually unavailable and traffic is dense, is a burden and restricts one's ability to move around. Thus, compatibility with the context, which includes a range of tangible and intangible systems, is necessary. The local context influences user-product interaction by imposing certain conditions, which may enhance or hinder people's experiences with products and their assignment of value. Specifically, a set of common behaviors, or ways of doing things; systems, with which products interface, such as infrastructure, organization of space, and institutional and geographical factors; and socially and culturally shared meanings, such as common symbols, rituals, and traditions, can be significant in shaping user value. Therefore, the same product may be assigned a different value by users in different contexts. For Holbrook (1999), the value of a product is not only relative to the context but also to the alternative products users are acquainted with. Valuation involves concepts such as evaluation and judgment, which imply a comparative process, and choice-making and preference for one option over another.

Dependence on the Stages of Experience

In marketing research, a distinction exists between pre-purchase and post-purchase value (Gardial, Clemons, Woodruff, Schumann, & Burns, 1994; Jensen, 2001; Parasuraman, 1997; Woodruff, 1997). The former refers to expectations regarding the value a product is going to deliver that are formed prior to purchase of the product. An individual's anticipation of the experience a product may provide can be a strong factor motivating that person's decision to acquire and use that product. Post-purchase value, on the other hand, involves value realized through the use of a product. Therefore, one can rightfully argue that post-purchase value, or value-as-use, is more closely tied to the realities of the user's context. However, this should not go beyond speculation since research on value as use is still limited.

Value may emerge not only in purchase and use situations, but also in the disuse or dispossession of a product. Sometimes, the conscious act of not owning or not using a product has a value for its user too. For example, the choice not to own a mobile phone can be of value to people, as it can make them inaccessible and can give them control over their time. Owning but not using certain products can be of value as well. For example, many women are proud of the fact that they always cook at home, and that they do so without using many gadgets. For them, the convenience some small appliances might provide would take away from the sense of fulfilling the role of being a good mother and caregiver.

Parasuraman (1997) hypothesizes that value can also vary over time as the level of experience users have with a product alters. As users move from being what he calls first-time to short-term and long-term users, their value assessment criteria may change. Obviously, their experience with a product will change, as "every experience both takes up something from those which have gone before and modifies in some way the quality of those which come after" (Dewey, 1938, p. 34). The prior experience and knowledge that users have in relation to a product might be especially relevant factors in their value assessment of products with a high learning curve, such as information products.

Multidimensional

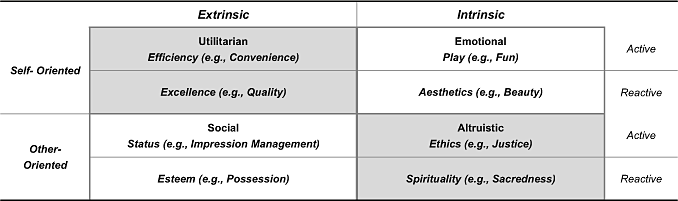

Based on the definition of value as experience, Holbrook (1999) identifies three dimensions on a continuum characterizing user value, which are (1) intrinsic-extrinsic, (2) self-oriented versus other-oriented, and (3) active-reactive.

The intrinsic-extrinsic dimension relates to whether a product is valued as an end per se because of its qualities, or for the means or functions it offers that help users accomplish certain ends. For example, a product such as Stark's Juicy Salif is usually assigned intrinsic value, because it is appreciated as an end in itself, rather than as a means for squeezing lemons. A self-oriented versus other-oriented distinction corresponds to whether a product is valued because of its benefit to the user or because of the reactions it draws from others. A car, for example, has a self-oriented value because its functional qualities bring certain benefits, such as convenient transportation or safety, to its user, but it also has other-oriented value because it signifies social status and evokes reactions from others. Finally, the active-reactive dimension represents a distinction regarding whether there is a manipulation of a product by the user or vice versa. Art objects, for example, have a reactive value, because their benefit results from passive admiration. A drill, on the other hand, has an active value because its benefit arises from the user actively interacting with the product.

Types of User Value

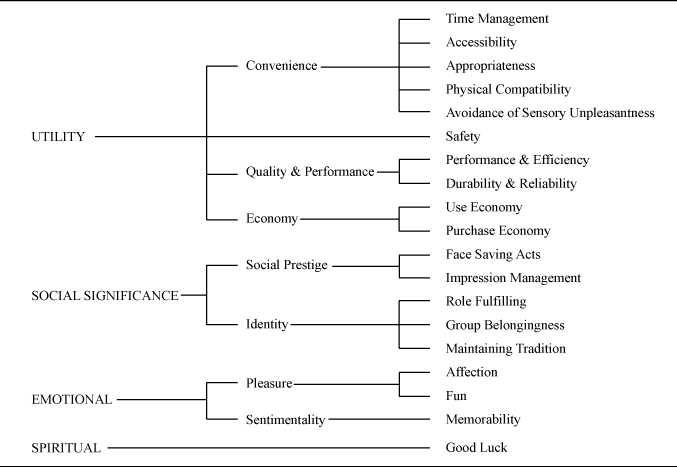

To make things more complicated, it should be noted that different types of value might emerge from users' experiences with products. For example, within the framework of Holbrook's (1999) axiological taxonomy, based on the three dimensions presented above, we can recognize a variety of different value types. These are: efficiency, excellence, play, aesthetics, status, esteem, ethics, and spirituality values (Table 2). In my own study of kitchens, with participants from Turkey and the United States (Boztepe, in press), I identified four major categories of user value: (1) utility, (2) social significance, (3) emotional, and (4) spiritual values (Figure 1).

Table 2. Types of User Value (Adapted from Holbrook (1999))

Figure 1. Categories of User Value.

Utility Value

Utility value refers to the utilitarian consequences of a product, for example the fact that it might enable the accomplishment of a physical or cognitive task. It encompasses the values of convenience, economy, and quality as sub-categories. In practice, convenience is defined in various ways that include concepts such as accessibility, appropriateness, avoidance of unpleasantness, or compatibility to the local context rather than just as a matter of saving time and effort. For example, rather than as a means for economizing time, Turkish women use a refrigerator as a tool for reordering and managing time. They use it for storing elaborate homemade dishes in semi-prepared form or extra homemade pastries for later use. This is not saving time per se, but rather shifting cooking activity to a different time slot. Note that the notion of managing time involves relocating time as desired instead of reducing the time it takes to accomplish an activity.

Economy value is concerned with the economic benefits provided by products. These benefits include, but are not limited to, purchase economy, such as can be provided by low prices or flexible installment plans. While these are important, the long-term effects of a product on the family budget, or the economy-in-use, are an even more important value for users. For instance, American participants in the kitchen study primarily viewed their refrigerators as a means to beat high prices and save money through bulk buying and by taking advantage of special offers such as buy-one-get-one-free or family value packs. Value as quality can be broadly defined as an appreciation of a product for its inherent superiority, such as might be found in the durability of materials used to make the product.

Social Significance Value

Social significance value refers to the socially oriented benefits attained through ownership of and experience with a product. These include attainment of social prestige and construction and maintenance of one's identity. People use goods as markers of their relative position in the social nexus (Bourdieu, 1979/1984; Veblen, 2001). Even the most ordinary goods may develop into symbols, and people may interact with them in several ways to achieve social prestige and to maintain face (Goffman, 1967, 1974). Goffman views the self as a social construction, and the notion of face, "the positive social value a person effectively claims for himself by the line others assume he has taken during a particular contact" (p. 5), is one way of viewing it as such. Mere possession of a trendy object is often seen as sufficient to communicate a certain image of self.

The value of products as a means of achieving distinction from others through projection of an image one wishes to create, or through what Goffman (1959) calls impression management, however, is not related to the static ownership of products only and their use as labels, but also to how they are being utilized and what ends are achieved through their use. As Goffman notes, members, to use his term, employ a series of well-choreographed techniques in an attempt to control the impressions they form on others, just as an actor presents a character to an audience. Note that earlier the value of a refrigerator in the Turkish context was seen specifically in terms of its ability to enable time shifting through advance preparation and storage of homemade foods. From the perspective of social significance value, then, the same phenomenon here generates a reality of a kind in the eyes of the participants' visitors such that the hosts are always well-prepared for unexpected guests.

Emotional Value

Emotional value refers to the affective benefits of a product for people who interact with it, benefits such as pleasure or fun. Such benefits arise from affective experiences, which, according to Desmet and Hekkert (2007), occur on three levels: (1) aesthetic, referring to delight experienced in a sensory capacity, (2) meaning, referring to experiences that relate to one's personality or character, and (3) emotion, referring to the provocation of strong feelings such as love, anger, etc. While Norman (2004) describes the ascription of emotional value primarily as a psychological phenomenon, Desmet and Hekkert (2007) emphasize the context-dependent nature of affective experiences. For example, local perceptions of aesthetics might affect what users define as beautiful or pleasurable. These perceptions are sometimes driven by trends and fashions, which may also differ from one location to another. For example, small toy-like appliances in pastel colors prevail in Turkish households, where they are considered beautiful and pleasing, whereas American countertop appliances communicate an image of power, through an industrial look and capacity. Many of the American participants in the kitchen study mentioned that it is not just an issue of looks, but that they derive great pleasure from using powerful appliances, an experience that makes them feel like professionals. Emotional value is not only derived from the sensorial delight provided by the visual or kinesthetic qualities of products but also from the meanings ascribed to them. For example, American participants in the study invested effort in increasing the emotional value of their refrigerators and making them more pleasurable by adding magnets, children's drawings, and family photographs to the outside: "Each time I see my kids, my family…how much they have grown, it makes me happy," said one participant. Here, the happiness is derived not from the visual quality of the drawings and photos, but from their associations and meanings for the user.

Spiritual Value

Finally, spiritual value refers to spiritual benefits such as good luck and sacredness that are enabled by a product. For example, a spiritual element was discernible in the decoration of refrigerators in Turkish households. Many had nazar boncuğu (evil eye) magnets or stickers on the refrigerator doors, a symbol that is believed to guard against evil associated with envious or covetous eyes. (In Turkish culture, it is believed that the envy of others can cause harm, whether intentionally or not.) Also, many kitchens had bereket jars, a Turkish symbol for fertility and abundance, which contain samples of food that one wishes to be always abundant in the house. Other examples show that communication technologies are increasingly becoming enablers of spiritual experiences too. For instance, several websites have been set up that serve Muslims who live away from their home countries, allowing them to pay online and have sacrifices made on their behalf during Eid ul-Adha.

Of course, these value categories are not mutually exclusive, and the same experience with a product can impart different categories of value simultaneously and to varying degrees. For example, the emotional value most Turkish users aspire to create through decorating their refrigerators also generates convenience value by protecting the refrigerators from dust. On the other hand, there also seems to be the potential for trade-offs between different value types. For example, the social rewards and pleasure of preparing coffee manually might be preferred to the convenience provided by an electric coffee maker. So the question becomes, what are the mechanisms of compromise between different value categories and how do some value categories become foregrounded on a daily basis?

Design and User Value

For Cagan and Vogel (2002), design creates what they call value opportunity classes; that is, properties such as emotional appeal, aesthetics, identity, ergonomics, impact, core technology, and quality, which contribute to the overall experience of a product and relate to its value. They argue that the higher a product scores on each class the greater its value to users. But what Cagan and Vogel are putting forward as design's contribution toward creating these properties is still somehow vague.

In user-product interactivity, according to Jensen (2001), users form a relationship between certain product properties and the benefits they desire from a product. It is essential then that products have sufficient visible cues to signal their potential value to users. These cues are different from the semiotic or Baudrillardian codes, as they are not totally independent of a product's formal or functional characteristics. They do reside in the object, but are interpreted by the subject. Product properties are treated as cues, or indicators, of value. Through their visible and intrinsic characteristics, they convey certain uses and meanings, which are constantly matched and compared against the requirements of the user's context. My findings support the view that user value is created as a result of the harmonious combination of product properties and what users and their local contexts bring to the interaction with the product. In responding to the question of what constituted the source of value for them, participants often indicated specific product properties. In other words, on the face of it, they equated the source of value with the product properties themselves. In responding to the question of how a specific product property constituted the source of value, however, they often assumed the context of product use, and explained how that property fit into their behaviors, daily habits, etc. Zeithaml (1988) distinguishes between intrinsic or extrinsic cues or signals. Intrinsic cues are related to the physical configuration of a product. Extrinsic cues, on the other hand, are product-related but not part of the product, such as brand name, price, and level of advertising. Contrary to the colloquial belief that brand and price are the key factors in the assignment of value, Zeithaml suggests that users rely more on the intrinsic cues, except when these are not available or when their evaluation requires too much effort or time. However, the cues that motivate a customer's initial purchase of a product may differ from the criteria that connote value during use.

Design uses all available means, including form, color, texture, materials, affordances, symbols and metaphors, as such cues to communicate value. However, claiming that design creates value perhaps would be an overstatement and would be falling into the trap of the objectivist views discussed earlier. Design starts with the intention to generate value and it has the characteristic of persuasiveness, as Buchanan (1985) puts it.

Heskett (2002b) talks about "the interplay between designers' intentions and users' needs, perceptions, and goals" (p. 54). So, developing the capacity of objects for value is perhaps a better definition of design's role in value creation. In developing that capacity, designers' heightened understanding of users' contexts and their reasons for and methods of imbuing objects with different types of value is essential.

Tools for User Value Research

In the early 1980s, several inventories, such as Values and Lifestyles (VALS), were developed to measure consumer value (Woodrudff & Gardial, 1996). The claim of such methods is to segment people according to their enduring beliefs. VALS, for example, consists of categories such as innovators, achievers, thinkers, etc. While these categories have their basis in reality, they are highly stereotypical and concerned only with generalities. Such groupings can help designers establish the general positioning of a product, but they fall short in helping designers identify details that make the difference in people's experiences with the product.

Other tools, which have also been developed in the marketing field, build on the means-end model, such as Gutman's (1982) laddering method. They suggest that product attributes, which take place on the bottom of a means-end chain, are linked to psychological or social payoffs at the highest level. These methods are based on the assumption that values (i.e., the deeply held and enduring beliefs regarding what is right or wrong) drive the selection and use of products. The means-end approach could be a significant means to track how basic product characteristics such as color, form, texture, etc. can lead to practical or social benefits of a highly abstract nature. Yet, this approach treats value assignment as a cognitive process and psychographic phenomenon and does not sufficiently account for contextual factors. It has already been mentioned that value can change from one context to another. Therefore, research on value cannot afford to ignore situational and cultural contexts. Swidler (1986) suggests a shift of focus from values as the ultimate determinant of the ends to what she calls the tool-kit of habits, skills, styles, and beliefs from which people construct strategies of action. People in different parts of the world may share common values while they continue to exhibit different behaviors and experiences with products. Understanding users' goals is essential, but the same goals can be achieved in many different ways. So, if we build on the notion of value as experience, we should also look at these various ways of doing things, since experiences are attained through activities, among other things. By examining the activities surrounding the use of a product, it is possible to learn much more about the specific ways through which the product leads to desirable consequences. As Parasuraman (1997) states, perhaps the construct of value is so complex and involves so many variables that no single measurement scale would be sufficient for capturing it. Therefore, a range of tools, from more open-ended ethnographic investigations to specific cognitive scales, are needed to deal with the slippery concept of value.

Conclusion

This paper has barely touched upon the surface of a vast topic and has raised more questions than it has answered. Having a subject as complex and as multidimensional as this, and a research discipline as young as design, the questions that deserve research attention are so many. One of the key areas research should focus on is the dynamics of value assignment. For that, there is a need for more empirical studies, since much of the development on the issue of user value has been conceptual. Ethnographic research focusing in depth on value assignment for each value category and for different product groups is particularly needed for building a fuller understanding of the complexities of the contextual nature of user value assignment. For example, further research involving different products could shed more light on the role of product properties in the assignment of value. Does the value assignment change for different product categories? How do certain product properties become salient? What are the structural and cognitive characteristics of value assignment?

Similarly, further research could unveil some patterns regarding the context dependency of different product categories. The effect of user context on value may call for special attention, especially with respect to the internationalization of products, and the design of ubiquitous, social, and collaborative computing solutions. In a similar vein, although this study has provided an overview of what different value types are and how different local elements play a role in users' value assignment, we need to trace the issue further and to look at the different value categories in more depth. Also, we need a better understanding of how value changes at different stages of interaction with a product. Are there predictable triggers that lead to value change? To what extent can context be predictable?

Yet we must not forget that building an understanding of the complexities and mechanisms of user value would not be sufficient alone. Design is action-oriented. As Simon (1996) defines it, design aims to change the existing situation into a preferred one. Therefore, particular design research effort is needed for developing tools and methods applicable in design practice that would enable designers to be active in enhancing value creation. In other words, theories of "middle range" (Merton, 1968) are needed to link theories and the daily practical issues of designers. The next step in user-centered design then becomes how designers deliver user value. Even this brief review of some models of user value shows that achieving such ambitious goals is not an easy task, and may be only possible from a multi–disciplinary perspective and by putting under scrutiny design knowledge, skills, and methods.

References

- Baudrillard, J. (2006). The system of objects (J. Benedict, Trans.). New York: Verso. (Original work published 1968)

- Baudrillard, J. (1998). The consumer society: Myths and structures (C. Turner, Trans.). London: Sage. (Original work published 1970)

- Belk, R. W. (1987). Identity and the relevance of market, personal and community objects. In J. Umiker-Sebeok (Ed.), Marketing and semiotics: New directions in the study of signs for sale (pp. 151-164). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of judgment of taste (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1979)

- Boztepe, S. (in press). Toward a framework of product development for global markets: A user-value-based approach. Design Studies.

- Buchanan R. (1985). Declaration by design. Design Issues, 2(1), 4-22.

- Butz, H. E., Jr., & Goodstein, L. D. (1996). Measuring customer value: Gaining the strategic advantage. Organizational Dynamics, 24(1), 63-77.

- Cagan, J., & Vogel, C. M. (2002). Creating breakthrough products: Innovation from product planning to program approval. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Rochberg-Halton, E. (1981). The meaning of things: Domestic symbols and the self. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Desmet, P. M. A., & Hekkert, P. (2007). Framework of product experience. International Journal of Design, 1(1), 57-66.

- Dewey, J. (1966). How we think. New York: Free Press.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Free Press.

- Drucker, P. F. (2001). The essential Drucker: The best of sixty years of Peter Drucker's ideas on management. New York: Harper Business.

- Frondizi, R. (1971). What is value? LaSalle, IL: Open Court.

- Fulton Suri, J. (2003). The experience evolution: Developments in design practice. The Design Journal, 6(2), 39-48.

- Gale, B. T. (1994). Managing customer value. New York: Free Press.

- Gardial, S. F., Clemons, D. S., Woodruff, R. B., Schumann, D. W., & Burns, M. J. (1994). Comparing consumers' recall of prepurchase and postpurchase evaluation experiences. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2), 548-560.

- Gell, A. (1986). Newcomers to the world of goods: Consumption among Muria Gonds. In A. Appadurai (Ed.), The social life of things (pp. 110-138). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ger, G., & Belk, R. W. (1996). I'd like to buy the world a Coke: Consumptionscapes of the "less affluent world." Journal of Consumer Policy, 19(3), 271-304.

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Anchor Books.

- Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face behavior. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. New York: Harper & Row.

- Graeber, D. (2001). Toward an anthropological theory of value: The false coin of our own dreams. New York: Palgrave.

- Gutman, J. (1982). A means-end chain model based on consumer categorization processes. Journal of Marketing, 46(2), 60-72.

- Heskett, J. (2002a, September/October). Waiting for a new design. Form, 185, 92-98.

- Heskett, J. (2002b). Toothpicks and logos: Design in everyday life. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Heskett, J. (2002c). Values and value in design. Unpublished manuscript, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago.

- Holbrook, M. B. (Ed.). (1999). Consumer value: A framework for analysis and research. New York: Routledge.

- Jensen, H. G. (2001). Antecedents and consequences of consumer value assessments: Implications for marketing strategy and future research. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 8(3), 299-310.

- Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. A. (2005). Blue ocean strategy: From theory to practice. California Management Review, 47(3), 105-121.

- Leont'ev, A. L. (1978). Activity, consciousness, and personality. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Levitt T. (1981). Marketing intangible products and product intangibles. Harvard Business Review, 59(3), 94-103.

- Margolin, V. (1997). Getting to know the user. Design Studies, 18(3), 227-235.

- Margolin, V. (2002). The politics of the artificial: Essays on design and design studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Marx, K. (1990). Capital: A critique of political economy (Vol. 1) (D. Fernbach, Trans.). New York: Penguin. (Original work published 1887)

- Melican, J. (2004). User studies: Finding a place in design practice and education. Visible Language, 38(2), 168-193.

- Merton, R. K. (1968). Social theory and social structure. New York: Free Press.

- Norman, D. A. (2004). Emotional design: Why we love (or hate) everyday things. New York: Basic Books.

- Overby, J. W., Woodruff, R. B., & Gardial, S. F. (2005). The influence of culture upon consumers' desired value perception: A research agenda. Marketing Theory, 5(2), 139-163.

- Parasuraman, A. (1997). Reflections on gaining competitive advantage through customer value. Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 154-161.

- Redstrom, J. (2006). Towards user design? On the shift from object to user as the subject of design. Design Studies, 27(2), 123-139.

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theater and every business a stage. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. New York: Free Press.

- Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: Free Press.

- Simon, H. A. (1996). The sciences of the artificial. Boston: MIT Press.

- Swidler, A. (1986). Culture in action: Symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review, 51(2), 273-286.

- Vandermerwe, S. (2000). How increasing value to customers improves business results. Sloan Management Review, 42(1), 27-37.

- Veblen, T. (2001). The theory of the leisure class. New York: The Modern Library.

- Woodruff, R. B. (1997). Customer value: The next source of competitive advantage. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 139-153.

- Woodruff, R. B., & Gardial, S. F. (1996). Know your customer: New approaches to customer value and satisfaction. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2-22.