Design Enters the City: Requisites and Points of Friction in Deepening Public Sector Design

Antti Pirinen*, Kaisa Savolainen, Sampsa Hyysalo, and Tuuli Mattelmäki

School of Arts, Design and Architecture, Aalto University, Espoo, Finland

Design is increasingly deployed by governments and cities to address social and policy-related problems and to develop public services and organizations towards more citizen centeredness. Design activities in complex and hierarchic public organizations easily meet challenges, making their impact elusive. More knowledge is needed on the organizational requisites of public sector design. This article provides an empirical analysis of the challenges and opportunities of embedding design in a large public organization, as perceived by fourteen city officials. The case organization, City of Helsinki, has been a pioneer in using design at the strategic level and using it widely in its organization. The results show that differences between the design field and the public sector not only offer complementarities but also create friction in the practical utilization of design. Moreover, the discontinuity and fragmentation of design activities, the highly variable maturity levels within the city organization, the integration of design into projects, and more encompassing leadership, change management, and implementation of the results of design projects were seen as future development areas.

Keywords – City Organization, Co-design, Participatory Design, Public Sector, Service Design.

Relevance to Design Practice – Design professionals and civil servants can utilize the results to enhance the impact of design activities in the public sector.

Citation: Pirinen, A., Savolainen, K., Hyysalo, S., & Mattelmäki, T. (2022). Design enters the City: Requisites and points of friction in deepening public sector design. International Journal of Design, 16(3), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.57698/v16i3.01

Received December 15, 2021; Accepted November 21, 2022; Published December 31, 2022.

Copyright: © 2022 Pirinen, Savolainen, Hyysalo, & Mattelmäki. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted following the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: antti.pirinen@aalto.fi

Antti Pirinen is University Lecturer in Spatial and Service Design at the Department of Architecture at Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture. His research addresses human-centered, participatory and co-design mainly in interior space, the built environment, and related services. He has also explored questions around inclusive and resident-driven housing design and development. Antti’s interest in the emerging design activities in the public sector and the role of design in public governance arises from his long-term experience of collaborating with cities and other public organizations, as well as from teaching a course on current discourses and approaches within the public sector design in the multi-disciplinary Master’s Programme in Urban Studies and Planning.

Kaisa Savolainen is Postdoctoral Researcher at Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture, and School of Science. Her doctoral research focused on human-centered design, and she is interested in the point of view of versatile users. She has over ten years of experience working in the private sector and participating in public organizations. This work has focused on the user and citizen participation, co-design, user research, and user experience. Her research focuses on the human perspective of systems, services, and communities, and she has published in design, human-computer interactions, sustainability, and eHealth.

Sampsa Hyysalo is Professor of Co-Design at Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture. His research focuses on designer-user relations in sociotechnical change. This includes engagement in participatory design, co-design, open and user innovation, open design, peer knowledge creation, user communities, citizen science, and user knowledge in organizations. Sampsa has studied co-design in the public sector, first in health care contexts for nearly two decades, and more recently in participatory design of a major cultural sector project, the Oodi library in Helsinki. He has published over one hundred academic works, including several books and 80 peer-reviewed articles.

Tuuli Mattelmäki is Associate Professor in Design at Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture, and acts as the head of the Department of Design. She is an expert in service design and co-design, specializing in implementing creative design approaches to support change. Tuuli has worked closely with the public sector for more than a decade in research and education collaborations. She has published several articles on design’s role and impact in the public sector, and she has edited a book that focuses on how service design enters the city organization, focusing on collaboration with the City of Helsinki in particular.

Introduction

Recent decades have seen growing recognition of the potential of design in public sector innovation. Design has gained prominence as a distinctive strategy, process, and toolkit in the public realm (Design Commission, 2013; Design Council, 2013; Bason, 2016 & 2018; Julier, 2017). Governments and cities all over the world have established design programs and labs to tackle the increasingly complex demands for public governance and service provisioning that are accelerated by demographic, social, environmental, and economic change (Bason & Schneider, 2016; Tõnurist, Kattel, & Lember, 2017; McGann et al., 2018; Bailey & Lloyd, 2016; Ferreira & Botero, 2020; Julier & Leerberg, 2014; Cities of Design Network, n.d.). These new types of design activities characteristically rely on citizen-centered and collaborative methods and solutions. In contrast to the tangible outcomes of the established public planning and design system with its customary, predetermined processes, such as urban plans, buildings or service environments, they typically deal with more open-ended, intangible, strategic, and systems-level issues.

Design as a novel and unfamiliar approach with fundamentally different values and logic than public administration challenges the traditional ways of doing things in the public sector and often necessitates organizational change in order to redeem the value from design (Bason, 2016; Bailey & Lloyd, 2016; Kimbell & Bailey, 2017; Deserti & Rizzo, 2014; Sangiorgi, 2011). Imposing design upon public institutions easily creates friction that hampers the success of design and the implementation of outcomes (Junginger, 2015; Hyvärinen, Lee, & Mattelmäki, 2015; Pirinen, 2016). Moreover, the ambiguity and versatility of design make it hard to define and pinpoint its contribution. The impact and value of public design, let alone its return on investment, remain challenging to decipher.

This study aims at shedding light on the particular challenges or points of friction that arise when design encounters a large public organization. The focus is on a city as a complex organization with particular characteristics and demands for design. While the role of design in state government has lately been studied avidly, there is less research on cities as the promoters, customers, and beneficiaries of design (Julier & Leerberg, 2014). Previous research has mainly looked at the utilization of design in cities on the project level (e.g., Hyvärinen et al., 2015; Pirinen, 2016; Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2018; Svanda, Čaić, & Mattelmäki, 2021). In this study, the scope is broadened to encompass the whole organization. The interest is mainly in the relationship between design and the city organization as divergent domains.

Here, a distinction needs to be made between the city as a geographic, built, social, cultural, and economic entity, and the municipality as its governing body. In this article, we use the term ‘City’ with a capital first letter to refer to the City of Helsinki as the municipal administrative organization that steers the operations of the city and takes care of its public services (see also Figure 3). Design activities in the broader urban sphere and in the private sector are outside the scope of this study. In distilling findings from the City of Helsinki to other municipal administrative organizations, we refer to these administrations also as City or Cities.

The study is grounded on empirical data collected in a project commissioned by the City of Helsinki in 2019 and realized by the authors as consultants through a university. The project aimed to investigate the types and perceived benefits and challenges of design activities in the City of Helsinki, the capital of Finland, which has been one of the pioneers of public sector design. Although design has been utilized in the City organization for over a decade, there was little knowledge about its actual nature and value, an understanding of which would be crucial for developing the design activities further and improving their effectiveness. From an academic perspective, access to the City organization provided an opportunity to study the practice of public sector design in a first-mover setting and thus contribute to research in the rapidly evolving field.

The structure of the article is as follows: After introducing the premises and research question, we provide an overview of the emergence and characteristics of public sector design. The key barriers to implementing design in public organizations (as identified by previous research) are discussed in the fourth section, followed by an overview of the history and current state of utilizing design in our case organization, the City of Helsinki. The execution of the interview study is explained in the sixth section and the results are presented in the seventh, which forms the central part of the article. The final section summarizes the study’s contribution and addresses its limitations and further research needs.

The Emergence of Public Sector Design

Design, famously defined by Herbert Simon (1996) as “devising courses of action aimed at changing existing situations to preferred ones” (p. 111), has a long history of serving public governance. Political scientists and philosophers have noted the central role of design in making laws and political aims tangible, exerting control over citizens, and governing our everyday life (Foucault, 1991; Pfaffenberger, 1992; Shove, 2003; Tunstall, 2007). In this view, designed artifacts directly participate in the governance of social order, norms, and interactions.

In the Nordic countries, designers and architects have historically been involved in materializing the institutions and services of the welfare state and providing a good life for all (e.g., Berglund, 2013). Design in its traditional, tangible forms has been firmly established as part of the public governance system, most notably via the hierarchic city planning and urban design processes.

The interest of this study is in the new types of design activities in the public sector that have gained prominence during the last two decades. Design, typically the more intangible and open kind, has been adopted by governments, municipalities, and civil society for addressing complex social and policy problems (Julier, 2017; Design Council, 2013; Bason, 2016 & 2018).

This development is driven by the shift in the design field towards a more strategic and systems-level focus, as well as increasing social and ethical concerns (Danish Design Centre, 2015; Buchanan, 2001; Papanek, 1984; Ceschin & Gaziulusoy, 2020; Hyysalo, Marttila, Perikangas, & Auvinen, 2019). It is supported by the growth of design practices that emphasize human-centred and intangible aspects, most importantly participatory design and co-design (Schuler & Namioka, 1993; Simonsen & Robertson, 2013; Sanders & Stappers, 2008; Steen, 2013; Botero, Hyysalo, Kohtala, & Whalen, 2020; Kohtala, Hyysalo, & Whalen, 2020), design for services (Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011; Sangiorgi & Prendiville, 2017; Penin, 2018), design for policy (Bason, 2016 & 2018; Howlett, 2019; Junginger, 2013), and design thinking in business and management (Dunne & Martin, 2006). Consequently, design is seen as a promising tool for societal innovation and transformation. Its role in value creation has also been acknowledged by national design strategies and innovation policies (Bason & Schneider, 2016; OECD, 2017).

The demand for design is connected to the increasing complexity of the problems faced by public organizations and the quest for participation and citizen engagement in society at large, including public administration. The public sector has turned to design because it offers participative tools for addressing wicked problems and brings in a more diversified understanding of social needs and values (Buchanan, 1992; Blomkamp, 2018; Wagle, 2000; Hyysalo, Marttila, et al., 2019; Hyvärinen et al., 2015). The public design movement is linked to existing traditions of design participation in the public realm, relying on ideas of citizen empowerment, democracy, openness, social innovation, and mutual learning (Ehn, Nilsson, & Topgaard, 2014; Manzini, 2015; Till, 2013; Sanoff, 2000; Arnstein, 1969; Dalsgaard, 2012; Hyysalo, Marttila, et al., 2019), as well as linking to participatory governance as a set of deliberative practices aiming at more responsive services, social cohesion, and enhanced trust in politics and governance (Fischer, 2012; Bradwell & Marr, 2008).

At the same time, the expansion of design is tied to new public management, neoliberalization, privatization, and the encroachment of market logic in the public sector (Julier, 2017; Berglund, 2013; Kimbell & Bailey, 2017). It is driven by dismantling the welfare state, austerity measures, and demands for efficiency through the streamlining and digitalization of services. Herewith, citizens are increasingly rendered as individual consumers with subjective demands and responsibilities (Thorpe, 2018; Rebolledo, 2016). From a neoliberalism perspective, as argued by Julier and Leerberg (2014), public sector design can merely be seen as an “opportunist” practice filling in a vacuum left by the “loss of any coherent governmental strategy in the social and economic sphere.”

Against this complex and multifaceted backdrop, public sector innovation labs have begun to emerge globally, with MindLab in Denmark (2002–2018) and Policy Lab in the UK (2014–) as the protagonists of a more design-led approach (Bason & Schneider, 2016; Tõnurist et al., 2017; McGann et al., 2018; Bailey & Lloyd, 2016). The labs typically develop public services and policies on the bases of flexible governance, co-production/participation, and experimental culture. Particularly in Latin America, they often engage closely with civil society and activist movements (Ferreira Litowtschenko & Botero, 2020). Finnish examples include the Helsinki Design Lab at the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra (2009–2013) and design units in government ministries, such as the Inland team in Immigration Services (2017–2019) and the D9 digital team in the State Treasury (2017–2018) (Komatsu et al., 2021; Mergel, 2019).

Along with the state government, cities and municipalities are utilizing service design and co-design in specific projects or as a broader strategy for advancing change. Among the first cities to adopt an explicitly design-led strategy for social and economic regeneration were Kolding in Denmark and Montréal in Canada (Julier & Leerberg, 2014; Rantisi & Leslie, 2006). The UNESCO Creative Cities Network (Cities of Design Network, n.d.) presently counts among its members 43 Design Cities that seek to profile themselves through the extensive use of design. Examples of strategic design units in cities include the Civic Service Design Studio in the City of New York (NYC Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity, n.d.) and the Helsinki Lab in the City of Helsinki that will be discussed later. A growing number of (service) designers are nowadays directly employed in city departments and units, and cities are major procurers of services from private design consultancies.

The new design activities in cities, while different from the habitual regeneration strategies of urban design, place branding, and cultural planning (Julier & Leerberg, 2014), also intertwine with them. The activities touch upon the discourse on creative cities (Landry, 2012) and the shift toward participatory planning and urban development (Forester, 1999). In addition to services and the built environment, design plays a role in city branding and marketing, where it is harnessed as a vehicle for competition between urban regions (Rantisi & Leslie, 2006). Since 2008, the World Design Capital program has been influential in promoting the use of design as a strategic driver in cities (World Design Organization, n.d.). The economic value of design and the creative industries to cities has also been highlighted (Florida, 2002; Howkins, 2001; Montalto et al., 2019). However, there is little research on the new type of (service, strategic, and policy) design activities in city organizations.

Positioning Design within Public Organizations

The public sector encompasses public institutions, enterprises, and services on all levels from state to regional and local governance. To contextualize the design practices within this heterogeneous setting and to sharpen the picture of public organizations as the target system of design, we shall briefly discuss the characteristics, scope, actors, and ways of organizing design in public organizations.

While the range of methods and types of design activities in the public sector is highly diverse, they typically involve, or develop conditions for, some degree of citizen participation. Depending on the practitioner and context, the activities discussed in this article can be called design, design thinking, service design, participatory design, co-design, social design, or policy design. In Helsinki, the term city design (in Finnish, kaupunkimuotoilu) has also been commonly used.

Terminological ambiguity notwithstanding, the approaches share some common characteristics that could be described as the core competencies of design in the public sector. In light of the literature, these include human centeredness and sensibility to the diversity of user needs; a solution and innovation-oriented process; a participatory, collaborative, and cross-siloed way of working; a holistic and systems view of complex problems; the ability to give concrete shape to abstract concepts and ideas; creative, visual, and tangible tools; and skills in prototyping (Design Council, 2013; Bason, 2018, pp. 175-184; Blomkamp, 2018, p. 732; Penin, 2018, p. 153; Rebolledo, 2016; Hyvärinen et al., 2015).

Previous research opens up a multi-layered view on public design practice, showing how designers operate on project, organization, network, or systems levels, and focus on solutions in different scales and degrees of tangibility. Designers in public organizations can work in an operational or strategic role and with diverse aims, such as improving existing solutions, envisioning future services, or designing for complex service ecosystems (Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011, pp. 202–204; Sangiorgi, 2015; Vink, Edvardsson, Wetter-Edman, & Tronvoll, 2018). The institutional goals and arrangements also necessarily shape the design activities (Vink et al., 2018).

Aside from adding value to customers (citizens) through solutions that better meet their needs, design’s intrinsic value to organizations has been recognized. Engagement of users, employees, and management in design activities can support the alignment of goals, social cohesion, and mutual learning (Meyer, 2013). Accounts of public sector design discuss the scaling up of small experiments as seeds of systemic change and emphasize the transformative potential of design in public organizations (Deserti & Rizzo, 2014; Sangiorgi, 2011; Junginger & Sangiorgi, 2013; Vink et al., 2018).

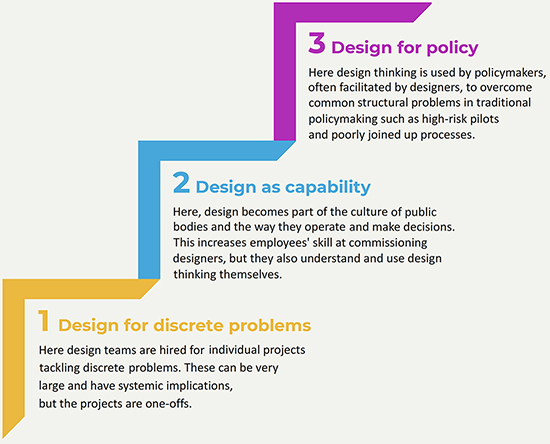

The public sector design ladder by the Design Council (see Figure 1) illustrates the perceived evolution of the scope of design in public organizations, ranging from one-off projects to design as a widely adopted organizational capability, and further, moving onto design for policy matters. The Danish design ladder similarly posits design on steps from no design to design as strategy (see Yeo & Lee, 2018). Even if the ascending hierarchy of approaches and the transitionary process proposed by these frameworks should be assessed critically, they illustrate the expansion of design’s conceptual and practical scope, and highlight design as a valuable organizational capability.

Figure 1. The public sector design ladder (adapted from Design Council, 2013, p. 30).

In addition to variation in scope and purpose, the position, actors, and degree of integration of design in public organizations vary. Internal design resources can be arranged in different ways, from central specialized design units to separate design teams inside divisions and to distributed design expertise, following a top-down or bottom-up fashion (Meyer, 2013). Within and beyond organizational boundaries, design can be delivered by an embedded designer, internal agency, external agency, brokered intervention, a design-led startup service, or no-designer design work (i.e., civil servants using design methods on their own) (Design Commission, 2013, p. 31).

Integration of design with the functions and culture in an organization is stressed as a prerequisite for it to develop into an organization-wide practice (e.g., Svengren Holm, 2013). Junginger (2009) identified four degrees of integration: design as an external resource; design as part of some organizational function; design at the core of the organization; and design thinking and methods are integrated into all aspects of the organization as means to inquire about the future and to develop integrated solutions (see also the precursors, Dumas & Mintzberg, 1989, on corporate design management).

Challenges Identified by Previous Research

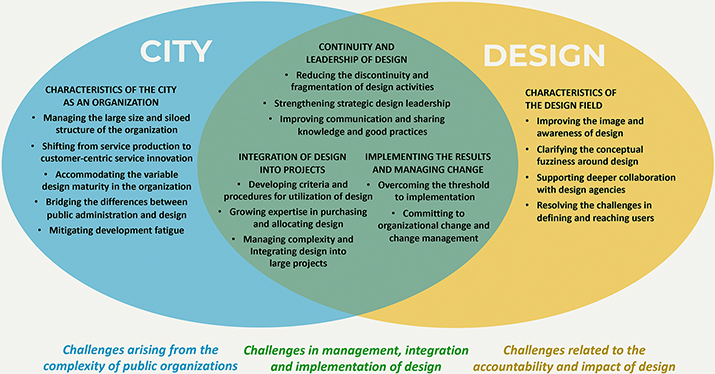

Research on design, organizational studies, and public management bring up several factors that impede the effectiveness of design activities on different scales, ranging from singular methods and projects to organization, network, and systems levels. Building upon the previous section, the key challenges can be grouped into three broader themes that relate to different parts in the system of public sector design, namely: challenges arising from the complexity and institutionality of public organizations; challenges related to the accountability and impact of design; and challenges in management, integration and implementation of design. The main challenges, opened up below in more detail, will be returned to in the discussion section and reflected against our empirical findings.

Challenges Arising from the Complexity of Public Organizations

The highly complex, interdependent, and institutionalized public governance system as such poses fundamental challenges to designers. Public organizations typically have a siloed and hierarchic structure, follow rigid administrative procedures governed by law, and rely on political decision-making processes (Bason, 2016). The design problems in the public sphere are similarly complex and systemic, involving multiple stakeholders and legislatory and other constraints (Buchanan, 1992; Blomkamp, 2018). Moreover, there is great variation in public organizations in terms of organizational purpose, existing organizational design approaches, and design practices (Junginger, 2015). Friction arises when new design practices meet the strong design legacies and traditional service provisioning models in public organizations (Junginger, 2015; Bradwell & Marr, 2008).

Introduction of design to public administration also calls into question its prevalent mental models, values, culture, and power relations (Vink et al., 2018; Bailey & Lloyd, 2016; Bason, 2016). Shift to citizen-centricity challenges the status quo and meets organizational inertia (Svanda et al., 2021). The leap required for designers to grasp the complexities of the public context and for civil servants to accept design’s experimentality and uncertainty is long and necessitates cultural change (Blomkamp, 2018). As designers in public organizations have little decision-making power, their contribution may be limited to cultivating a citizen-centered and collaborative design culture (Komatsu et al., 2021). The redistribution of power implied by co-design and the opening of governance in order for it to be redesigned by people are hard to achieve in the public sector (Sangiorgi, 2011; Tunstall, 2007; Hyysalo, Hyysalo, et al., 2019).

Design work is as well hampered by general challenges in cross-organizational collaboration. Prejudices and misconceptions, differences in language and culture, and conflicting goals and expectations among actors have been identified as barriers to co-design (Pirinen, 2016; Bailey, 2012). Stakeholders come with their fundamental assumptions, beliefs, values, and norms regarding the design task that are hard to make explicit and change (Junginger & Sangiorgi, 2009). Collaboration is also hindered by a lack of trust (Clarke et al., 2021; Hakio & Mattelmäki, 2011b). Accommodating multiple ways of knowing and the orchestration of collaborative innovation across professional boundaries is difficult (Staszowski, Brown, & Winter, 2016; Bason, 2018; Botero et al., 2020; Hyvärinen et al., 2015).

Challenges Related to the Accountability and Impact of Design

The legitimacy and credibility of design(ers) in the public governance system pose a central challenge. Among others, Bason (2016) has pointed out the fundamentally different values of government and design that create “an inherent clash between the logic of administrative organization and the sensibilities of designers” (p. 30). This can lead to misunderstandings and apprehension, but also to enthusiasm and the appropriation of design as a vehicle of transformation. In public design, the rational hierarchy of administration is met by designers’ synthetic, emotional, and intuitive thinking and making (Svanda et al., 2021). The situation is not made easier by the fact that the word design itself is confusing, and design as a professional field is unknown to civil servants (Design Commission, 2013, p. 16).

On the level of projects, there is resistance within the expert-driven public organizations to new ways of working, and the unconventional visual, tangible, and playful methods of design can be seen as inappropriate (McGann et al., 2021; Bailey & Lloyd, 2016; Kimbell & Bailey, 2017). Stakeholders may also refuse to accept designers’ framings of the design challenges (Svanda et al., 2021).

Importantly, the reliability and evidence of design have been questioned. Blomkamp (2018, p. 734) stated that public co-design claims to be transformative but has not really been able to provide evidence of its effects. Design is perceived by civil servants as not “sufficiently representative, quantifiable, or reliable” (Bailey & Lloyd, 2016, p. 3626)—as a superficial fad, incapable of creating profound change. This is connected to difficulties in measuring the impact of design (Bason, 2018, p. 267). The entanglement of design with other development activities in organizations makes isolating its specific effects as a component hard and would necessitate new, more nuanced metrics, particularly with regard to the strategic level of design (Björklund et al., 2018; Hannukainen et al., 2020).

A particular problem in public sector design concerns its representativeness. Design’s striving for user profiling and individual solutions contradicts the central ideal in public governance of developing services for all citizens (Hyysalo, Hyysalo, et al., 2019). In participatory design, the equitability of processes and their accessibility to a broader range of people should be addressed to avoid power distortions and pseudo-participation that is devoid of real impact (Arnstein, 1969; Till, 2013).

The demand for the accountability of design in regard to the users also puts pressure on making the designers’ processes more transparent. Designers in public projects need to balance between top-down imperatives and citizen’s hopes and wishes. Their work is also under public scrutiny in a different way than in the private sector. As put by Thorpe (2018), “When dealing with ‘tricky’ challenges, shared visions may be perceived as deceptions if left unrealized” (p. 168). Thus, designers should acknowledge the inescapably political nature of their work (Staszowski et al., 2016).

Researchers have also called for a critical examination of the power issues in public sector design in order to avoid perpetuating existing power structures and inequalities, particularly when working with marginalized groups (Julier, 2017; Kimbell & Bailey, 2017). This resonates with Berglund’s (2013) notion of tame public design serving the powerholders without question. Similarly, Sangiorgi (2011) argued that designers should become more aware of their ethical responsibility and the impact of their work on people’s lives instead of relying on design as a patent solution or ideology.

Challenges in Management, Integration, and Implementation of Design

The practical adoption of design in public organizations raises further challenges, implying the need for more systematic design management. In large organizations, lack of organizational commitment and support to design activities and inconsistent leadership and management all form barriers (Pirinen, 2016; Hyvärinen et al., 2015; Holmlid & Malmberg, 2018; Jensen & Petersen, 2016; Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2018; McGann et al., 2021). The disjunction between top-down strategic goals and bottom-up design initiatives poses another challenge (Bradwell & Marr, 2008). Evidently, practical restrictions—like a lack of time, funding, or competent personnel—also limit the success of design (Pirinen, 2016; Hyysalo, Hyysalo, et al., 2019). The “time and cost of co-designing solutions and political pressures to achieve quick deliverables” commonly create tension (McGann et al., 2021, p. 309).

The discontinuity and fragmentation of design activities in the public sector form a significant problem. For instance, many public innovation labs have been relatively short-lived, depending on temporary funding and political changes (Kimbell & Bailey, 2017; Tõnurist et al., 2017; McGann et al., 2021). Another problem is the poor integration of design with those areas and processes upon which it is supposed to impact, making it misfocused, disconnected, or asynchronous (Pirinen, 2016; Hyysalo, Marttila, et al., 2019). This is influenced by the unfamiliarity of design to civil servants and by the scarcity of (service) design expertise in public organizations. In this context, the procurement of design has been recognized as an important, yet undermined, area that highlights design tenders, briefs, and expertise in purchasing design as success factors (Park-Lee & Person, 2018). The challenge of integration arises on the organizational level as well. Svengren Holm (2013) pointed out that for design to become a strategic resource, it should be functionally, visually, and conceptually integrated throughout development processes and communicate actively with other functions. The fragmentation and disintegration of design also hamper organizational learning (Meyer, 2013).

The implementation of the results of design work often becomes a threshold. The dissemination of outcomes typically relies on just a few insiders and meets institutional inertia in organizations amidst competing ideas and a focus on core operations. Translation of the outcomes across divergent domains and organizational borders is needed for them to be adopted. (Hyvärinen et al., 2015; Pirinen, 2016; Svanda et al., 2021.) The adoption and scaling up of service concepts require development and change in the service organization (Overkamp & Holmlid, 2016; Sangiorgi, 2011; Deserti & Rizzo, 2014). Furthermore, complex problems in public settings are rarely finally solved and necessitate the continuous adaptation of solutions over time with users and other stakeholders (Bason, 2018, p. 186; Overkamp & Holmlid, 2016). Community building around design and contextualization of design outcomes and tools into everyday organizational practices can create conditions for design to achieve deeper impact (Yee & White, 2016; Yeo & Lee, 2018; Bailey, 2012).

Design in Helsinki

The City of Helsinki—the capital city of Finland that has 650 000 inhabitants, nested in a broader capital region of 1,2 million inhabitants—has been one of the global forerunners among cities in utilizing design across the organization (City of Helsinki, 2019). The wide adoption, diversity, and relatively long history of design activities in the City of Helsinki make it an interesting study case on public sector design, learnings from which could benefit both research and design practice.

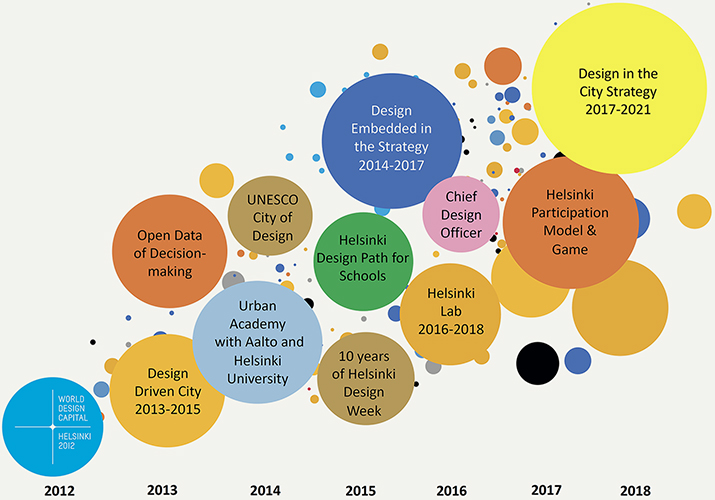

The history of significant design initiatives in the City of Helsinki is depicted in Figure 2. The World Design Capital year of 2012 can be seen as the turning point for realizing the value of design for the City and its inhabitants. It highlighted the social and everyday role of design, introduced new areas (like service design) to the general public, and raised the City’s international profile through design (City of Helsinki, 2021a; Berglund, 2013). Another key milestone was the Design Driven City initiative that ran from 2013 to 2015 and brought city designers to work inside City departments and projects, relying on service design as well as rapid experiments and prototyping. In 2016, Helsinki became the second City in the world to employ a Chief Design Officer to lead the design activities (cf. Julier & Leerberg, 2014). Around the same time, the Helsinki Lab was established as an internal team in the central administration to support the implementation of design in the organization. Design was also embedded in the City’s strategy for 2017–2021 (City of Helsinki, 2021a & 2021b). Lately, designers working in the public sector in Finland have founded a network for sharing experiences and developing the professional field, and Helsinki has taken an active supporting role in this network (Leppänen, 2019).

Figure 2. The design journey of the City of Helsinki (2019).

The current communications material of the City of Helsinki states that “Design is a strategic tool for Helsinki to build the most functional city in the world and smooth everyday life for all. Design benefits everyone and people of all ages from toddlers to seniors in Helsinki” (City of Helsinki, 2021b). This poignantly echoes the modernist social agenda of design. The stated benefits of design for the City of Helsinki include improving the customer experience of services, reforming the operating culture and organization of the City, and building a distinctive city brand.

The municipal design journey of Helsinki has been an organizational learning process where understanding the value of design and the maturity level in utilizing it has gradually grown through the accumulation of projects and experience. Early adventures in service co-design (Hakio & Mattelmäki, 2011a & 2011b) have given rise to more sustained and embedded design practices and the value of design has been widely embraced within the City organization (City of Helsinki, 2019).

Design in the City of Helsinki can essentially be defined as the user-centered and collaborative development of public services, the built environment, and the City’s organizational culture, using specific methods and tools that originate from the design field. In practice, the design activities are very diverse. Our case study revealed 23 distinct types of design activities in the City that could be grouped into six clusters, namely: the design of service solutions, design in the built environment, design in the development of an organization, design know-how and training, design in participation and collaborative work, and design in strategy and branding work (Hyysalo et al., 2022). The aims, processes, and outcomes were significantly different in each cluster. Examples of design-driven projects by the City include customer profiling in youth services, service design in public transportation, and large construction projects like Helsinki Central Library Oodi that opened in 2018, for which service design was used extensively in the development phase (Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2018; Hyysalo, Hyysalo, et al., 2019).

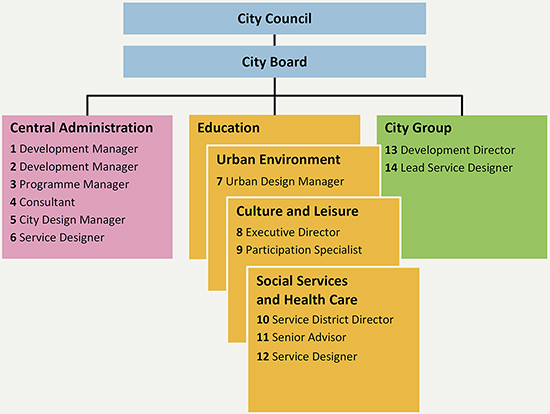

To grasp the whole context of design activities in Helsinki, it is necessary to briefly describe the City’s administrative organization, which was renewed in 2017. Under the politically elected City Council and City Board, there are four large divisions (see Figure 3). The Urban Environment Division is in charge of land use and city infrastructure, as well as buildings and public areas. At the same time, the Culture and Leisure Division takes care of cultural, youth, and sports activities. The Education Division provides education from preschool to upper-secondary levels. The Social Services and Health Care Division delivers social, health care, and hospital services. In addition, a City Group contains the business entities and foundations controlled by the City and the joint municipal authorities, such as the Helsinki Regional Transport Authority (City of Helsinki, 2020).

The City’s Central Administration includes the City Executive Office, which functions as the central planning and executive body for the city council, board, and mayors. The Chief Design Officer, the Helsinki Lab, and most other strategic and organization-level design work are situated within this department. However, design activities also occur inside the divisions and in many projects. Aside from the few in-house designers working in Central Administration and the divisions, design work is procured from commercial (service) design agencies.

The Method and Participants

To trace the challenges of embedding design in the City of Helsinki, we have conducted an interview study with City officials who have experience in design work in the organization. The study was part of a small commissioned project initiated and funded by the City Executive Office. The four authors realized the project as consultants through a university. The project members included three City representatives with active roles. The initial goals for the project were defined by the City and iterated together with the researchers. Aside from the perceived challenges discussed in this article, the interest was in the types of design activities in the City (see Hyysalo et al., 2022).

The authors planned the interview study independently, following discussions with the client and insight from previous research. The City representatives provided background material from inside the organization and helped in identifying the interviewees. The aim was to find people from different divisions who had broad experience of design activities in a managerial or more hands-on role. Some of the participants had been advocates of design in their organization, while others had encountered design from a more external perspective. In total, 14 persons in different roles and with varied experience were interviewed during the spring and summer of 2019 (see Figure 3 and Table 1). The project members from the City were also among this group (interviewees 4, 5, and 6).

Figure 3. The interviewees positioned in the city organization.

Table 1. The design experience of the interviewees.

| # | Position | Division | Experience |

| 1 | Development Manager | Central Administration | 12 years of development work involving creative industries. Ensuring the design perspective in different development projects. |

| 2 | Development Manager | Central Administration (earlier in Education) | One year in current role, and ten years in Education. Brought service design to Education through several projects in administration and teaching. |

| 3 | Program Manager | Central Administration | Ten years in the organization in different digital development projects. Last four years actively promoting service design and user participa-tion. |

| 4 | Consultant | Central Administration | Ten years in the organization. Has promoted design thinking and or-ganized service design training throughout the years. |

| 5 | City Design Manager | Central Administration | One year in the organization. Promotes service design across the or-ganization and leads the Helsinki Lab. |

| 6 | Service Designer | Central Administration | Coordinates service design projects and helps projects in utilizing design. |

| 7 | Urban Design Manager | Urban Environment | Ten years in the organization. About half of work related to city de-sign, the rest to street lighting and urban planning. |

| 8 | Executive Director | Culture and Leisure | Seven years in the organization. Promoting design thinking in the or-ganization through different projects and development work. |

| 9 | Participation Specialist | Culture and Leisure | Ten years in the organization in different positions. Conducting and promoting participatory design in different projects including several large scale building projects. |

| 10 | Service District Director | Social Services and Health Care | 14 years in administrative role, and six years in current role. Leading projects and participating in projects that involve service design. |

| 11 | Senior Advisor | Social Services and Health Care | 18 years in development role, 20 years in the organization. Collabora-tive development work already since the beginning of 2000’s, later service design work in development projects. |

| 12 | Service Designer | Social Services and Health Care | First year in current position. Promotes design thinking in the organi-zation and participates in procurement processes with service design perspective. |

| 13 | Development Director | City Group | Eight years in the City. Currently in marketing, participated in pro-jects that brought user-centered design to city development, also ex-perience of communication regarding the projects. |

| 14 | Lead Service Designer | City Group | Ten years in the organization. Participated in different projects related to service design as well as visual design. |

As seen above, six of the interviewees were from the Central Administration of the City, mainly from the City Executive Office and the Helsinki Lab. The divisions were represented by six persons and the City Group by two. Notably, there were no interviewees from Education and only one from Urban Environment. However, one interviewee from the Central Administration had previously been working in the Education Division. Most of the participants were in managerial or development-related positions. Four worked as service designers or design managers in their unit and had an education in the field. All the interviewees had participated in several projects where design methods had been applied to digital or physical services, the built environment, or strategic development. Further details on the participants and their experience in design are presented in Table 1. Pertaining to the anonymity of the study, individual participants are not referred to in the results section.

The semi-structured interviews, lasting about one hour, covered the design activities in which the interviewee had participated, as well as the advantages and challenges of applying design in the projects and the City organization. The second author conducted the interviews, which were audio-recorded and transcribed. A project member from the City took part in some of the interviews.

This article concentrates on the impediments related to applying design that emerged from the interviews. The focus is primarily on the participants’ responses to the following three questions, although other instances in the material where related issues are discussed have been included in the analysis as well:

- What do you see as the biggest remaining challenges for applying design in the City?

- Do the challenges and opportunities vary depending on the project?

- What have been the typical challenges in different types of projects?

The analysis of the written interview data was done by the first author, who was also responsible for writing the main sections of this article. The analysis followed the principles of qualitative content analysis (Schreier, 2012). The transcribed material was read closely in light of the research question, the key insights were coded and grouped into broader categories based on their affinity, and the categories were abstracted into broader themes that could be described and validated against the data and previous research. A tentative guiding framework for organizing the findings was provided by the literature review that suggested to look into the City organization, the design field, and the application of design in the City as key areas (see the fourth section).

To ensure the trustworthiness of the study, the preliminary results were discussed and evaluated by the whole research team together with the project members from the City. After this evaluation, the grouping was slightly modified, and the results were condensed and clarified. These results were then presented to a larger group of City officials in a workshop where they had the opportunity to comment on and evaluate the themes. The workshop had 16 participants from the City of Helsinki, including seven of the interviewees (1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 12). The other participants were officials from different divisions who also had some experience of working with design. The workshop discussions verified that the recognized challenges were valid and highlighted the importance of some of them. (Iterations were suggested for the typology of design activities discussed in another article by Hyysalo et al., 2022.) Throughout the process, the role of the City employees was to act as informants with knowledge about the target system and to assess the findings for their part to increase the reliability of the study. They did not interfere with the analysis or impact the final results. Possible biases in the study are discussed in the conclusions.

The project results, including the challenges of applying design, have been previously published as a practically oriented report submitted to the client (City of Helsinki, 2019). This article deepens the findings and connects them to the broader research discourse.

Requisites and Points of Friction in Design in the City Organization

In the interviews, the City of Helsinki officials elaborated on a range of issues that challenged the deeper and wider uptake of design in the City. These arose from their personal experiences and what they had learned from various projects and from discussions with colleagues. These issues can be categorized under five broader themes that shall be opened up in the following and reflected in the challenges identified by previous research. The first two themes highlight the fundamental characteristics of the City as a public organization and those of the design field as sources of friction between the two domains. The three remaining themes deal with practical friction areas between the City organization and design that can impede the effective utilization of design.

The Characteristics of the City as an Organization

Managing the Large Size and Siloed Structure of the Organization

The City of Helsinki is the largest employer in Finland, with around 39 000 employees, ranging from teachers to health care personnel and construction workers, to mention just a few groups. The siloed structure of the organization, with each division and unit focusing on its distinct core operations and having its own organizational culture, was deemed to hinder collaboration and the exchange of ideas. Indeed, the diversity of functions within the City and the interconnections within this diversity are far greater than those that would be present in a private company of the same size, focusing on one or a handful of business areas. The participants stated that the sheer size and scope of the City as an organization made it difficult to relate design projects to the organization’s development and to get a complete picture of it. Previous research has also recognized this primary difficulty of the size and diversity of public organizations (e.g., Bason, 2016; Pirinen, 2016). The overarching organizational design challenge opened up by the citizen-centric perspective was coined by one interviewee as follows: “Can we get closer to operating as one City towards the citizens, being more consistent across the organization, and managing the holistic user experience?”

Shifting from Service Production to Customer-centric Service Innovation

The City organization was described as enormously expert driven, based on a clear organizational structure wherein each educated specialist has their own pre-defined tasks and responsibilities, and often also significant power in their area of expertise. The growing demand for citizen-centeredness and cross-disciplinary collaboration in the City organization challenged the expert culture and created friction with it: “Our organizational DNA derives from the hierarchic and bureaucratic mindset of public administration. We have solid expertise in our domain. How can you bring something new into this world where people are top experts in their field?” The interviewees pointed out that user-centered and participatory approaches were easily seen as an unnecessary disturbance to the professionals’ process and a threat to their expertise. A service designer from the Social and Health Care Division noted: “One challenge is the attitude: are we experts or in a service occupation? It’s painful for people to let go of the expert’s crown. If I suggest doing things a bit differently, it’s perceived as contesting [their expertise].”

Several interviewees felt that the City management was divided into “modern” leaders who promoted a new, more agile and citizen-centered operational culture and an “old guard” who adhered to traditional views on service production and management, emphasizing top-down control and resource allocation. The importance of the management culture, the orientation of individual managers in supporting design (or not), and the difficulty of embedding design into established production systems are well-known from previous research (Hyvärinen et al., 2015; Junginger, 2015; Pirinen, 2016). The suggested polarization of the City management with respect to adopting design is a potentially interesting finding related to the extent to which design has already been integrated into City administration. Some managers embraced it, while others saw limited value in it. This division is likely to not just be about the individual orientation and skills of the managers and experts (see Bailey & Lloyd, 2016; Blomkamp, 2018) but more deeply rooted in the nature of the tasks and responsibilities within and between divisions, as we discuss next.

Accommodating the Variable Design Maturity in the Organization

The primary tasks of the City divisions also impacted their possibilities and motivation for undertaking design endeavors. According to our interviewees, the more strictly regulated divisions (the Social Services and Health Care Division and the Urban Environment Division) had narrower leeway for new modes of design, while the more loosely regulated fields (the Education Division and the Culture and Leisure Division) had wider application potential and could take more risks, making them more fruitful testbeds for design. This is an interesting finding, although the challenge of embedding design into highly regulated systems like those of health care institutions has been recognized before (e.g., Hyvärinen et al., 2015; Pirinen, 2016).

Despite its hierarchical structure and the heavy responsibilities of delivering services determined by law, the Social Services and Health Care Division in Helsinki had made extensive use of service design, albeit with challenges in getting the results implemented. The approaches and principles of service design were widely understood in the division, and customer experience had been elevated as a driver for service development, partly because of competition with private service providers. “Our customers nowadays are very diverse and demanding, so we can’t develop the services just among the civil servants without understanding the customer experience,” explained a director.

Similarly, the Culture and Leisure Division and Education Division had adopted service design open-mindedly and implemented it rather extensively, even on the strategic level. It was pointed out that the purpose and core operations of the divisions made them more susceptible to human-centric and experimental approaches than the divisions focusing on essential services. As acknowledged by one participant: “Our topics are fun and nice to join in. But it’s important to remember that not all activities in the City are like that. Roadworks are basically not fun or the renewal of substance abuse and rehabilitation services. You can’t make nice videos about them.”

The participants deemed the Urban Environment Division to be on the lowest maturity level among the City divisions in terms of the utilization of co-design and service design. This was explained by its focus on the construction of the physical environment and its reliance on legally guided formal processes that require citizen engagement, as well as the strong existing design professions in the field (such as those of planners, architects, and engineers) who may question the relevance of service design. Evidently, the influential design legacies in this area form a barrier to new modes of design (see also Junginger, 2015). On the other hand, so-called city design, defined here as the design of the small-scale physical environment, is a well-established approach in the division. An interviewee from this division emphasized strong professional ethics as means to overcome barriers in cross-organizational collaboration: “All of us are trying to make a good and functional city. The shared goal makes things easier.”

The study showed that the degree of design know-how and the maturity level regarding the readiness and ability to use design varied considerably according to City division, unit, team, and employee (see also Junginger, 2015). This highlights the need for tailored design approaches and clear metrics for measuring maturity (see also Bason, 2018; Björklund et al., 2018; Hannukainen et al., 2020). The development of organizational design maturity, with design ranging from discrete projects to design as a shared capability and, further, design developing into systems and policy-level design (see Figure 1), is slow and requires support and mutual learning. In Helsinki, the Helsinki Lab was tapping into these needs by offering sparring to projects on design methods and by harmonizing the guidelines for commissioning design from external agencies.

Bridging the Differences between Public Administration and Design

The discrepancy between the rapid, experimental activities that are characteristic of design and the slow development of operations of the City that are foremost based on legislation and political decision-making was brought up by some participants. The large size of the City organization, and the hierarchic and siloed organizational structure and principles of operating a bureaucracy were deemed to impede fast-moving and experimentation-based ways of working. Hence, cultivating a culture of design experimentation in the City required (and continues to require) significant effort. As an example, design’s fine-grained identification of specific user groups, used for grasping the diversity of user needs and contexts, was at once seen as a welcome improvement and as contradicting the core principle of public services being offered equally to everybody (see also Hyysalo, Hyysalo, & Hakkarainen, 2019). However, differences between the underlying principles and practices of public administration and design also hold promise to complement each other. They may form the core reason why design potentially has much to offer in regard to renewing public sector organizations.

Mitigating Development Fatigue

Many interviewees expressed that continuous, overlapping development processes without sufficient prioritization burdened the City employees, reduced motivation, and caused the general development fatigue that is common to many public and private organizations today. The results of various development projects and ideation workshops were rarely translated into everyday practice, and previously developed tools were soon forgotten under new ones (see also Bailey, 2012). In this view, design was just one of many competing extra activities requiring the time and commitment of civil servants who were already busy with their core responsibilities (see also Pirinen, 2016; Hyvärinen et al., 2015).

Characteristics of the Design Field

Improving the Image and Awareness of Design

According to our informants, the notion of design was often perceived as strange, distant, and elitist by City employees. This quote is from a manager in Central Administration: “A surprising challenge when I started in this job was that design may sound elitist and alienating to people, whereas I see it as very hands-on activity, really looking with an open heart at what we see and hear, and being honest about everything that the users say.” There was little knowledge about the concrete advantages and good examples of design, which in turn hindered its adoption and internal promotion. Officials without design expertise tended to have a narrow understanding of design’s competencies and know-how, limited to visualization and facilitation of participatory workshops. In line with previous research, design was seen as a “glued-on circus trick” or a fashionable “jack-of-all-trades” attempt to solve complex problems with little realistic, in-depth application potential: “Sometimes I think that whenever we face a complicated or difficult issue, it’s like ‘okay, let’s invite some service designers here’” (see also McGann et al., 2021; Bailey & Lloyd, 2016; Kimbell & Bailey, 2017; Design Commission, 2013).

Design was described as being very different from the customary public sector development processes, a “chaotic and frightening” effort in which the initial “phase of distrust and disbelief” lasted a long time. This perception of human-centric design approaches is partly the corollary of the inherent tension between public service delivery and service innovation described above. However, the participants also brought up successful examples where initial reluctance towards design methods had led to an effective shift in the participants’ appraisal. In Social Services and Health Care, the value of design methods in facilitating collaboration has been recognized: “When they get what design is about, our customers and staff are quite willing to use service design tools and participate in joint ideation, as it’s an inspiring way to work.” Another interviewee emphasized the common goal brought in by design that different disciplines could relate to: “I see service design as a safe approach for renewing [the City] because nobody can deny that we are here for the customers.”

Clarifying the Conceptual Fuzziness around Design

As noted in the introduction, our interviewees used many different terms when discussing design activities in the City organization, such as design, service design, city design, human-centered design, participatory design, co-design, and co-creation. Design thinking, agile development, customer experience development, UX design, and business design were mostly favored by persons without a design education–persons having a business background or working with digital solutions.

The diversity of terms and approaches can be seen as a positive testimony to the versatility and value of design in the public sector. The use of particular terms was justified by their fit to the unit’s focus and practices. One of the design pioneers in the organization defended the term city design as “somehow quite permissive as it’s not an academically defined term or tied to a specific discipline.” However, in light of our data, the conceptual and practical fuzziness around design also hampered its evolution into a coherent organizational practice. The abundance of approaches in the design field made it difficult to comprehend. The City organization lacked a unified, commonly understandable, and communicable definition of design and a graspable clarification regarding its factually different subareas. One official provided material for this by defining design in the City as “design work that looks holistically at the activities, behavior and motivations of citizens.”

Supporting Deeper Collaboration with Design Agencies

Regarding the quality of design work sourced from external (service) design agencies, the civil servants felt that the end results delivered by design agencies were sometimes rather superficial or self-evident due to the lack of in-depth understanding of the target organization and of the services being designed. An in-house service designer expressed: “Design agencies just deliver the solutions they are paid for without necessarily collaborating [with the client]. This is a risk in many ways.” The interviews further revealed that the support needed from the City organization by the agencies during the projects and the collaboration between external designers, in-house designers, and City experts were often more significant than what had been prepared for or what could be provided. The consequence was nonetheless an occasionally experienced mismatch between the results and investment in design. This was also influenced by limited knowledge of design, unclear expectations, and inexperience in purchasing and allocating design work on the client’s side.

Whether or not the main problem lies in the lack of support and resources from the City or in the methods and practices of design agencies, this highlights the complexity of public organizations and design problems, and the need for designers’ profound engagement with the client organization (see also Sangiorgi, 2011; Hyysalo, Hyysalo, et al., 2019). It should be noted that the criticism did not concern all design work as examples of successful projects were also mentioned. The interviews covered a wide range of cases, ranging from lightweight “sticker workshops” to more long-lasting and impactful service design investments, such as in the case of Helsinki Central Library Oodi (Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2018). Interestingly, one interview reflected that traditional consulting firms were preferred in large projects instead of service design agencies because their deliverables are seen as more valid, which may indicate not only a difference in deliverables but also in the experience of and insight into how public organizations work and the requirements of that work. This implies that large, generalist consulting firms may be perceived as a less risky alternative to small service design agencies when using public funds.

Resolving the Challenges in Defining and Reaching Users

As mentioned earlier, design’s approach of identifying specific user profiles and taking them as a starting point for designing is generally considered problematic in public administration, which ideally seeks to develop solutions equally for all citizens. However, the idea of targeting some kind of average user was increasingly called into question among City experts and managers. There seemed to be a broader consensus that the more sensitive identification of real-life user groups and tailoring solutions to their needs would also be valuable in the public sector. However, the participants expressed concerns that a focus on too narrow customer segments in the design process would lead to inappropriate end results. At the same time, defining the appropriate target groups and reaching the actual persons to be studied and engaged in co-design was identified as a major challenge for the City organization. Reaching the right citizens requires time, financial resources, and skills that are presently rarely available. To this end, pairing design projects with internal development, such as more effective Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems and initiatives like the Friends of Culture and Leisure in the City of Helsinki, had been taken to gain a pool of citizens who could be contacted with a low contact price per person on a when-in-need basis (Hyysalo, Hyysalo, et al., 2019).

The Continuity and Leadership of Design

Reducing the Discontinuity and Fragmentation of Design Activities

Temporal and organizational discontinuity were identified as major impediments to the more impactful utilization of design in the City by nearly all respondents (see also Pirinen, 2016; Kimbell & Bailey, 2017). Contradicting the strategic meaning of design emphasized earlier, in the City organization, design was seen as a temporary, project-based activity rather than a permanently sustained development function to which the organization was committed through funding and strategy. Changes in the personnel employed on a project basis had led to discontinuity and interruptions in the transfer of knowledge. Based on the experiences of the interviewees, design projects in the City tended to be small and splintered. The dispersion of design work across the organization had led to overlapping activities and poor accumulation of learning. According to the City experts, it would be more fruitful to set up larger, coordinated design programs and processes that aim at systemic changes. This issue has also been discussed by other researchers (e.g., Junginger, 2009). One interviewee said, “We have done things right but stopped at that point when the right call would have been to invest more.” This problem is also illustrated by Helsinki’s design journey, which comprises relatively short-lived initiatives (see Figure 2).

Strengthening Strategic Design Leadership

The lack of the sufficiently high-level strategic design leadership that is required to guide design work and to direct resources to it was seen as a further organizational challenge (see also Pirinen, 2016; Hyvärinen et al., 2015; Holmlid & Malmberg, 2018; Jensen & Petersen, 2016; Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2018). It seems that the current roles of the Chief Design Officer and the Helsinki Lab do not entirely enable this. There is no central body to lead and manage the City’s various design activities. Participants were worried about the lack of clearly defined objectives, strategies, and roadmaps, both at the City level and in individual design projects. They also pointed out that the City management and the activities around design and participatory work should be presented to the citizens in a more unified way.

A subsequent challenge in the City organization concerned the relationship between central and peripheral design activities. The ownership of design is currently concentrated in the Central Administration, along with belonging to the Helsinki Lab and the Chief Design Officer, but this was perceived as remaining relatively distant from the City divisions, where designers met the concrete reality of service production and the customer interface (see also Bradwell & Marr, 2008). The central design unit was thus still seeking its role somewhere between strategic design leadership on the City level and effective servicing of the design work and personnel in the divisions.

Improving Communication and Sharing Knowledge and Good Practices

According to several interviewees, the benefits and good examples of design were not known inside the City organization, nor among the citizens, because too little attention was given to openly communicating them. Unawareness of previous projects’ end results and the good practices and tools developed in them had led to “continuous re-invention of the wheel” as many staff members in new projects typically started to explore the opportunities of design from scratch. On one hand, the problem concerned the sharing of knowledge internally across the large organization, “So that if someone develops a good concept, others could adopt it and modify it for their own field.” On the other hand, the challenge was how to present the successful design stories to external stakeholders, including citizens, both in a compelling way and internationally: “The story that we want to communicate internationally about the aim and purpose of the design activities has not been very clear. [Some other cities] are much better in telling these stories.” This issue connects to the role of design in city branding and marketing (Rantisi & Leslie, 2006).

The Integration of Design into Projects

Developing Criteria and Procedures for Utilization of Design

The early use of design in any organization tends to proceed through a growing network of people taking advantage of design in projects when favorable opportunities arise. Moving from such an early utilization of design to more widespread deployment calls for systematization in how design is used, and in which projects and project phases it is used. This problem was mentioned by a manager from Social and Health Care: “The utilization of design should be more systematic. It should be embedded into all service development projects, and design professionals should always be involved when we are developing services together with the customers.” The interviewees identified several current challenges related to planning and procuring design and integrating design into projects in an impactful way. Firstly, the criteria had not yet been developed for the use of design in projects across the City or within its divisions. Decisions to include design as a component depended on individual project managers with varying degrees of knowledge, prior budgeting, or connection to wider development activities. Design was thus not necessarily used where it was most needed and was easily left as a disengaged part of the project (see also Pirinen, 2016). This goes back to the previously discussed issues of varying design maturity, fragmented design activities, undefined types of design contributions and the value they bring, and the lack of central design leadership.

Growing Expertise in Purchasing and Allocating Design

One of the City officials summed up: “We have terribly little in-house expertise [in service design], and we don’t know how to integrate it into the service development process or how to purchase it.” In line with previous research (Park-Lee & Persons, 2018), the importance of the purchasing stage as a success factor for design and the need for special expertise in formulating effective and well-targeted design tenders and briefs came up in the study. Currently, it was difficult to bring qualitative criteria into the cost-driven public procurement process with tenders and contracts that guided the purchase of design in the City. A lack of know-how in purchasing design had also led to unsuccessful projects. Purchasing skills would include recognizing the need for design, defining design briefs in relation to broader goals, describing the expected outcomes for agencies, finding the right actors to contribute from the organization, and experience in budgeting design work.

Also, finding the right place and scope for design methods in development projects in relation to available resources and the desired impacts continued to present challenges: “Have we really figured out what we are doing? Have we defined the scope correctly, and are we even purchasing the right thing from the design agency?” As put by one expert, seeing the point in the project when the customer perspective and the design methods “fit in well” requires experience. The difficulty also concerned identifying the points in the development of broader systems where design could really make an impact. Often, too big challenges were taken up, or design was brought in too late (see also Pirinen, 2016; Hyysalo, Marttila, et al., 2019). The diversity of projects in the City meant that design could not be purchased or implemented with a single formula. The interviewees stressed the importance of common goals and coordination for design activities, the need to shift from small discrete projects towards more systematic utilization of design and long-term design partnerships, and knowledge sharing and training as means to enhance the organization’s design capability. A participant with long experience in development work reflected on the current challenges: “We have a lot of the kind of experimentation culture where we just do random things with random outcomes and don’t learn anything.”

Managing Complexity and Integrating Design into Large Projects

A particular challenge concerned integrating (service) design into large development and construction projects dealing with complex and holistic service environments, such as healthcare facilities or big public buildings. In those cases, the customer interface needed to be integrated with intricate backend functions where technology played a major role (see also Hyysalo & Hyysalo, 2018; Hyysalo, Hyysalo, et al., 2019; Dalsgaard, 2012). The project manager here had a demanding role in the nexus of the consultant network, client, and users. As put by one participant: “The project manager has to understand the user perspective, service design, spatial design, signage design, interior design, and manage the interface of a large network.” Impactful design work required an in-depth understanding of the target system, management skills, and the skills to facilitate cross-disciplinary collaboration. Expanding the client’s perspective and renewing the client’s operations were often crucial. As noted, the building and construction sector, with its strong professions and processes, also easily resisted the new modes of design.

Implementing the Results and Managing Change

Overcoming the Threshold to Implementation

In light of the interviews, it seems that the utilization of design in the City was as yet (over)concentrated on the early phases of design with limited carry-over. The new types of design predominantly focused on gathering user knowledge and ideating together, that is, in the early and more abstract stages of the design process. This tells about the perceived relative advantages that service design had acquired in comparison with more traditional customer research and marketing research, on the one hand, and in comparison with brainstorming and other ideation methods, on the other hand. However, service design tended to remain detached from its wider potential as the design activities rarely led to the design of solution concepts, let alone to concept prototyping. They thus remained distant from implementation and further iterative design in use, both of which could be equal strongholds of modern service design (Botero et al., 2020). However, it should be noted that the design activities in the City also served many other purposes than direct service development, such as serving City strategy, collaboration, and organizational change.

The interviewees argued that the present phase in the utilization of design in the City was characterized by enthusiasm in setting up design projects, yet paying less attention to their organizational ownership and having limited comprehension of their benefits to the City: “We start things easily, but the commitment of management to carrying the projects through after the initial development phase is rather low.” The results of strategic and service design work were rarely put into action or used for devising practical solutions or scaling up new tools in the City, especially when external agencies or development partners had the main responsibility (see also Svanda et al., 2021; Hyvärinen et al., 2015; Pirinen, 2016). This was recognized particularly in Central Administration: “There can be a huge number of projects and reports by different agencies, and nobody knows what has come out of them, how they are connected, or if any actions have been taken. Sometimes we could just pause the development and draw from what we have.” To overcome the implementation threshold, it was suggested that explicit emphasis should be placed in the project planning phase onto what the design project requires from the City organization and how the results will be harnessed.

Committing to Organizational Change and Change Management

The connection between design activities and organizational change in a context where the traditional ways of operating differed markedly from those of design was well recognized by the City officials (see also Deserti & Rizzo, 2014; Sangiorgi, 2011; Hyysalo, Hyysalo, et al., 2019; Hyysalo, Marttila, et al., 2019). A participant with experience in digital services opined: “It’s relatively easy to design a new service with users but really challenging to manage change [in the service organization].” Many interviewees saw design foremost as means of organizational change management, aiming at shifting the City’s operating culture and services so that they would become more customer-centered and responsive. As noted above, impactful design work would require more commitment to change among the managers and the whole organization, overcoming organizational siloes and hierarchies, and sufficient resources to manage organizational change and support the diffusion of new practices among the personnel, going beyond individual design projects. In cases where such wider commitment had been present, design had indeed been heralded as an enabler of a more customer-centric organizational culture. Still, in others, designers had been left to tackle the steering of long-term transformative processes with systemic ramifications without the needed long-term change management. This is one of the likely reasons behind many projects remaining in the early stage of orientation and the results of design projects not eventually becoming implemented.

Conclusions: Nurturing City Design