I Love It, I’ll Never Use It: Exploring Factors of Product Attachment and Their Effects on Sustainable Product Usage Behaviors

Michael C. Kowalski and JungKyoon Yoon*

Department of Human Centered Design, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Research on product attachment has shown that users tend to retain emotionally meaningful products longer and delay their disposal. This has been suggested to be more environmentally sustainable, though little empirical evidence of the actual long-term use of these products is available. Two studies sought to understand the factors of product attachment and their role in sustainable product usage behavior. Study 1 involved qualitative semi-structured interviews to understand users’ relationships with meaningful product possessions and how this connected to their long-term product use. Through an online questionnaire, Study 2 quantitatively investigated the relative roles of factors of product attachment in product usage behaviors. The results from both studies showed differing patterns of product use. While at times, products of attachment are used actively for their practical utilitarian purpose, at other times, they are set aside for more passive psychological reasons. In this passive use pathway, evidence was found of increased redundant product consumption to satisfy practical needs, contrary to expectations expressed in previous literature. Perceived irreplaceability of a product, while being most influential in stimulating higher levels of attachment, was associated with more passive use and redundant product consumption. This paper discusses implications for design practice with future research directions.

Keywords – Design for Sustainability, Industrial Design, Mixed Methods, Product Attachment, User Behavior.

Relevance to Design Practice – This research supports informed design decisions in fostering product attachment as a means of stimulating users’ environmentally sustainable behaviors by providing designers with evidence of which influencing factors of product attachment are associated with long-term product retention and continued usage.

Citation: Kowalski, M.C., Yoon, J. (2022). I love it, I’ll never use it: Exploring factors of product attachment and their effects on sustainable product usage behaviors. International Journal of Design, 16(3), 37-57. https://doi.org/10.57698/v16i3.03

Received November 3, 2021; Accepted November 23, 2022; Published December 31, 2022.

Copyright: © 2022 Kowalski & Yoon. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content is open-accessed and allowed to be shared and adapted in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

*Corresponding Author: jy846@cornell.edu

Michael C. Kowalski is a doctoral researcher in the Department of Human Centered Design at Cornell University, where he is a member of the Meta Design & Technology Lab. He has experience as a professional industrial designer in both corporate and consulting roles. His research seeks to empower designers through a greater understanding on the human dimension of socio-technical transitions to more sustainable futures.

JungKyoon Yoon is an assistant professor in the Department of Human Centered Design at Cornell University, where he leads Meta Design & Technology Lab. This research group investigates the long-term impact of design and technology on human behavior and social dynamics. His recent research focuses on experience design with an emphasis on affective experience, subjective well-being, and design-mediated sustainable behavior.

Introduction

Several years ago, Michael’s (the first author) aunt engaged him to design a dining table to be used for family meals in her home. Significant time and effort were spent on the aesthetic details, material selection, and functional proportions to facilitate large family gatherings. During construction of the table, her husband sadly passed away. Shortly before his passing, he gave Michael a small collection of wood from his workshop, knowing Michael would one day get use from it. Pieces from the material he left behind were then incorporated into the project. Upon delivery of the completed table, Michael explained these details to his aunt, which understandably brought on an emotional response. Upon hearing this, and with tears in her eyes, she told him, “I love it, I’ll never use it.”

As this opening passage illuminates, individuals can become deeply attached to product possessions, and this attachment, in turn, can affect the ways that they use these special objects. Product attachment, defined as “… the strength of the emotional bond a consumer experiences with a specific product” (Schifferstein et al., 2004, p.327), has been shown to stimulate people to retain products, delaying their disposal (Mugge, 2007). In this vein, design researchers have presumed that encouraging product attachment would lead to more environmentally sustainable outcomes by reducing continued product consumption (e.g., Mugge, 2007; Schifferstein, & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008; Page, 2014).

But what if we looked a bit further? What if we considered things like meaningful dishes on display but no longer used for serving food, a unique car sitting in the garage most of the year, or a pair of custom sneakers remaining unworn and kept untouched in the closet? When continued use is considered, it is unclear whether product attachment will always align with this more sustainable behavior prediction. A review of existing research suggests a possible conflation of the retention of products with more environmentally sustainable behavioral outcomes. To date, there appears to be limited empirical evidence around continued use and consumption habits related to the phenomenon of product attachment.

Figure 1. Furniture and furnishings awaiting landfill at the 1st author’s municipal waste station.

Product Consumption, Use, and Disposal

Questions on the relationships between products people purchase, use, and dispose of have significant environmental implications globally and increasingly in the United States. From 1960 to 2015, while the population of the U.S. rose approximately 79% (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019, 2020), disposal of durable goods, meant to last three or more years, rose more than 500%. Furniture and furnishings saw a 571% increase in disposal during this time, with an associated recycling rate of just 0.001%, the rest being landfilled or burned (U.S. EPA, 2018). These figures suggest that the average American is disposing of durable products at a rate nearly seven times that of individuals in the 1960s. This trend has mirrored increases in the consumption of physical space. The average newly built U.S. home, the place many products are used and stored, and a significant source of energy consumption, has increased by more than 1000 sq ft. in the past forty years (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2015), yet with fewer individuals per house as they’ve grown in size (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022).

As a response to these increasing consumption and disposal trends, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)(2018) has suggested the lengthening of product lifespans and the purchase of long-lived products. However, more subjective concerns may also be of equal importance in the disposal process (van Nes & Cramer, 2005; Mugge, Shoormans, & Schifferstein, 2008). One research study of European consumers found that while 22% of disposed durable products were “broken and did not function anymore;” 42% of disposed durable products were still “functioning properly” or “functioning properly but showed some wear and tear” (van Nes, 2003, pp. 97-98). Reasons for disposing of these still-functioning products included concerns related to style, issues of obsolescence, and a lack of emotional value. This finding suggests objective durability, combined with more subjective concerns about the ability of a product to endure over time, both play a role in product retention and disposal.

Drawing from these initial insights, this paper will present theoretical and empirical evidence to further the understanding of the relationship between influencing factors of product attachment and usage behavior. Specifically, our research addresses the following questions:

- Research Question 1: Does product attachment lead to uniform or varied behavioral outcomes at the use stage, aside from prolonged product retention? We are interested in understanding whether people still actively use the product for its practical and functional purpose once it has been retained.

- Research Question 2: If the use of products of attachment is varied, which of the influencing factors of product attachment play a role in promoting continued active, practical use, and which may reduce active use? As product attachment has been shown to involve multi-faceted influencing factors, we are interested in more clearly identifying which factors may play a role in varied patterns of use.

- Research Question 3: If a product of attachment is retained but no longer actively used for its practical function, is there a need for redundant consumption of additional products of the same type to fulfill that practical need? If correct, this scenario may question some of the suggested environmental benefits related to product attachment.

Two studies were conducted to obtain both qualitative and quantitative insights addressing these research questions. Key previous research related to product attachment has generally focused primarily either on qualitative methods (e.g., Odom et al., 2009; Page, 2014) or quantitative methods (e.g., Mugge, 2007; Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008) within each study respectively, with mixed-methods appearing to be employed less frequently. By employing mixed methods, the aim was to have direct access to complimentary data to draw on the strengths of each approach. Additionally, in analyzing the state of the art in research relevant to product attachment and product replacement behavior, van den Berge et al. (2021) note:

An important limitation of the literature on strategies to support the owned product’s value is that most are only theoretically discussed and empirical research (e.g., longitudinal studies, surveys, experimental and/or scenario studies) is lacking. Empirical research is needed to test their effectiveness on consumers’ replacement intentions and behaviours, and their potential for lowering the environmental impact of products. (p. 69)

Study 1 utilized semi-structured in-home interviews to investigate a wide range of products of attachment, as well as patterns of corresponding usage behavior. This study sought to confirm and elaborate on influencing factors of attachment presented in the existing research literature, as well as provide a grounded bottom-up understanding of product attachment. Building from this initial work, the second study utilized an online survey that investigated influencing factors of attachment and their relative relationships with usage and consumption behaviors.

Related Work: Factors of Product Attachment and Associated Concepts

Extant research on the concept of product attachment is situated within the fields of design, psychology, and consumer behavior, primarily focusing on the influencing factors that lead to attachment. Related concepts also include material possession attachment (Kleine & Baker, 2004), emotionally durable design (Chapman, 2009; Chapman, 2015; Haines-Gadd et al., 2018), and psychologically durable design (Haug, 2019). The latter is defined as “a design strategy with the purpose of increasing the period of time between the acquisition of a product and its replacement for reasons other than absolute or technological obsolescence. Thus, psychologically durable design concerns the durability of the product’s value” (p. 147). Similar ideas have also been investigated in other disciplines, such as the endowment effect (Kahneman et al., 1990) in behavioral science and economics, in which established ownership of products leads people to value them more highly than the market value, stimulating loss aversion and product retention.

This paper will follow most closely with the established definition and research surrounding the concept of product attachment, yet acknowledging these related concepts and consider a wide range of functional product possessions for analysis (for a broader overview of recent work on product attachment, see van den Berge et al., 2021). In this vein, the term product is used throughout this paper to broadly encompass a range of objects, from commercially available products, inherited or gifted objects, to custom-made items, for which there is an intended utilitarian function. What connects these items here are the implications when a lack of active utilitarian use of these items has the potential for increased product consumption.

In identifying influencing factors of product attachment, theoretical and empirical evidence has been documented for factors that include pleasure / product enjoyment; memories (particularly of persons, events, and places); self-expression / self-identity; product appearance; group affiliation; product utility or usability; reliability; and indispensability (Mugge, 2007; Mugge et al., 2008; Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008, Page, 2014). More recent work on the related concept of emotionally durable design has also focused on identifying factors relevant to the new product design process, including psychological and physical material concerns (Haines-Gadd et al., 2018).

Irreplaceability has also been identified as a primary factor related to product attachment. Schifferstein and Zwartkruis-Pelgrim (2008), through quantitative analysis, have stated “…the degree of attachment is most closely linked to the extent to which a product is irreplaceable” (p. 5). On implications for design, Mugge et al. (2008) have also suggested “To stimulate long-term attachment, designers should encourage a product’s irreplaceability by designing products that are inextricably bound up with their special meaning” (p. 433). In related work, Kleine & Baker (2004) state “material possession attachment is a multi-faceted property of the relationship between a specific individual or group of individuals and a specific, material object that an individual has psychologically appropriated, decommodified, and singularized through person-object interaction” (p. 1). Here a specific product that has been decommodified and singularized conveys a similar conception to a product being perceived as one-of-a-kind or irreplaceable.

Within the investigation of durable products, the closest to the perspective of this paper’s focus appears to be the interviews of consumers in the United Kingdom by Page (2014), in which participants identified products they felt attached to based on having a favorable appearance, pleasurable to use, or being sentimental. In synthesizing interviews, Page notes “Memories were found to be the most prominent area of attachment as they were frequently discussed in every interview. ...usability and pleasure were considered to be of next importance. Appearance and reliability were also significant, especially concerning motives for replacement” (p. 274). These findings suggest variations in appraisal and product usage behavior in the product attachment process dependent on differing areas of concern.

Product Attachment and Its Relevance to Sustainability

Within the above-mentioned body of research, there have generally been two areas of concern. The first is a better understanding and potential capacity to strengthen the psychological bond between an individual and a product of attachment (Mugge, 2007; Mugge et al., 2008, Chapman, 2009; Haines-Gadd et al., 2018). The emphasis has been on the increase in more positive emotions, though Mugge (2007) has noted negative emotions such as sadness may also be relevant in the attachment process. The premise of strengthening this bond is to create a longer-lived person-product relationship.

Connecting to this lengthened relationship, the second primary outcome is proposed greater sustainability in the product consumption process (Mugge et al., 2008; Chapman, 2009; Page, 2014; Ko et al., 2015; Haines-Gadd et al., 2018). The focus in this area has generally been on the retention of products of attachment and resulting delays in product disposal. Increased care, protective behaviors, and maintenance of products that exhibit attachment have also been highlighted (Mugge, 2007; Page, 2014).

Taking a wider view analyzing the range of strategies that have evolved related to design for sustainability, Ceschin and Gaziulusoy (2016) describe emotionally durable design and product attachment as being a relevant product-level strategy that can complement approaches aimed at more widespread systemic level change. Along with this, the authors note that more systemic level strategies aimed at addressing sustainability have generally focused more heavily on technical challenges, while being less informed on social and behavioral factors that play a critical role in the transition to more sustainable futures. To this end, the authors reiterate Mugge’s (2007) assertion that further research is needed across the entire lifespan of product usage to better understand the determinants of attachment and possible detachment from a product (Ceschin & Gaziulusoy, 2016).

Looking beyond the bounds of durable products, research relevant to fashion design on attachment to clothing items has found similar attachment factors, yet also begun to identify variations in behavior that may question a uniform environmental sustainability benefit through emotional attachment. In studies of primarily younger Finnish women (Niinimäki & Armstrong, 2013), and a broader demographic sample in the U.S. (Armstrong et al., 2016), these researchers have noted variations in clothing retention and active usage behavior dependent on whether pleasure in use or memories were the primary factor of attachment to a particular piece of clothing. Noting longer retention times with infrequent or non-existent usage of items stored away as mementos, they question whether there is actually an environmental benefit through this latter pathway and thus note, “[t]hese issues beg for further empirical inquiry” (Armstrong et al., p. 175).

This review of factors related to product attachment and proposed behavioral outcomes provides initial insights into how people form and experience these person-product bonds. With this paper, we aim to advance understanding and the empirical base relative to the roles these various factors play in stimulating attachment and subsequent product usage and consumption behaviors.

The Present Investigation

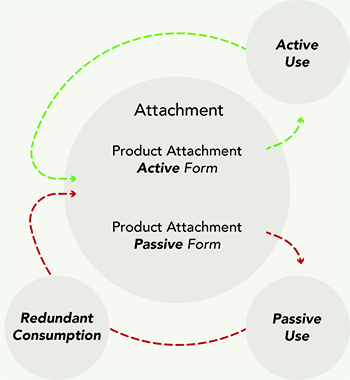

Based on the literature review and initial insights as shown at the start of this paper, we hypothesize that product attachment may follow dual pathways in relation to product use and potential redundant consumption of similar products. The pathway of active use of a product for its practical utilitarian purpose is the pathway of increased environmental sustainability benefits proposed in existing literature. Conversely, we hypothesize that there is an alternate attachment pathway related to more passive use of attached products that are simply retained for their psychological value but no longer used for their practical utilitarian purposes. These items may be transitioned to more decorative purposes or stored away indefinitely. In this scenario, while the specific product of attachment has been retained for a long period of time, it is expected that there will be a need for increased consumption of similar products to fulfill the utilitarian needs no longer being accomplished by the attached product. These propositions served to develop an initial conceptual framework guiding the development of the following two studies (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hypothesized Framework of Split Pathways of Attachment, Use, and Redundant Consumption

Study 1: In-Home Interviews on Product Attachment, Influencing Factors, and Usage Behavior

Study 1 utilized semi-structured in-home interviews to gain insights into specific products and perceptions of influencing factors of attachment. Further investigation was aimed at product usage behavior, with discussion and tangible evidence sought of active product use (e.g., performing a practical utilitarian function) or passive use (e.g., a reduction or elimination of practical use, with items retained primarily for their psychological value). Following with the usage behavior consideration, tangible evidence was sought of possible additional consumption of similar products. A qualitative approach was selected to begin the investigation in order to provide rich and detailed data on the subjective and objective factors related to attachment and continued use of products. The procedure was modeled on existing interview protocols termed material inventories developed by Blevis and Stolterman (2007) and Odom et al. (2009). This approach allowed for the development of a thematic analysis to construct key themes of psychological and behavioral factors of product attachment (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Thomas, 2006).

Method

Participants

Ten participants were recruited from the first author’s social network (four men and six women, ages from the late 20’s to early 70’s). Recruiting participants within this group allowed the benefit of a pre-established relationship before discussing their personal experiences that would likely be emotionally sensitive. The interviews took place over two weeks in February 2020 before quarantine restrictions were imposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the sample was relatively small and self-selecting, demographic variety was sought regarding age, gender, home type and size to gain rich insights into shared aspects of product attachment without being restricted to specific product types or user populations. Two participants were interviewed individually, and the remaining participants were married couples interviewed together. This latter format, while potentially altering the nature of personal disclosures about products of attachment, did allow for an additional point of reflection and discussion, as partners could provide a first-hand account of their mutual observations, as well as their own interpretations of each other’s behavior.

Procedure

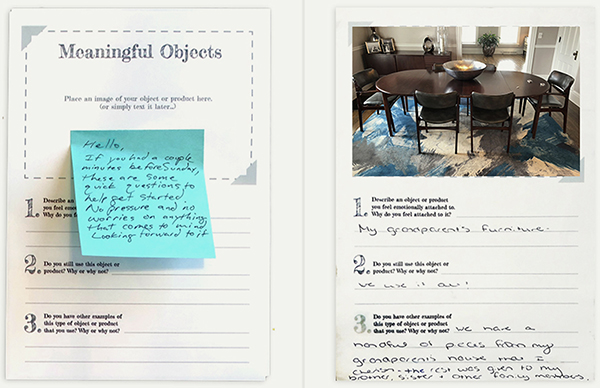

In order to sensitize participants to the nature of the questions in the study, a pre-interview survey card was delivered to their homes one week before the interview. The card provided short written prompts to consider existing product possessions to which the participants felt attached, photograph one of these products, and describe their reasons for feeling attached. The cards allowed the participants to begin the thought process of products to which they had an emotional connection in advance, and also provided a starting point for conversation in the interview. All participants noted reviewing the questions and had selected initial items to discuss. An example of the card can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Pre-interview survey card and completed example.

Interview sessions ranged from one to three hours, with the typical session lasting approximately 1.5 hours. While the length of interviews varied, they all followed a consistent semi-structured interview protocol. In certain instances, extended time allowed initially hesitant interviewees time for contemplation, trust building with the interviewer, and greater consideration of reasons products were most meaningful for them. The interview protocol was adapted from similar work by Odom et al. (2009) investigating product attachment and disposal, which identified a wide range of products of attachment. The question prompts utilized were originally derived from Csíkszentmihályi and Rochberg-Halton (1981). The initiating questions adapted for this study were:

- What things do you have that you feel attached to?

- Why do you feel attached to these things?

- What things do you have more than one of?

- What are the oldest things you have that you still use?

- What are the oldest things you have that you don’t still use, but would not discard?

- Why do you have more than one of some things?

- Why do you keep things you don’t use?

As the interviews were semi-structured, answers to these initial prompts were then followed with further questions utilizing a laddering technique (Reynolds & Gutman, 1988) to probe for further meaning, values, and explanation of deeper reasons for attachment and associated product usage behavior. The laddering technique seemed additionally beneficial with interviewees who needed time to gradually move into detail in the emotionally sensitive conversations and reflect in the discussion. All interviews were conducted in English, which is the participants’ first language. The interviews were audio recorded, and the products of discussion were photographed by the first author to provide visual data. The number of products discussed per participant ranged from four to twenty, with the average being ten products, and a total of 105 unique products.

Data Analysis

The audio files from the interviews were transcribed for use in a general thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Thomas, 2006). After initial organization of the data, de-identified transcripts were shared with a second researcher that had a general introduction to the research topic to ensure consistency of the data analysis. The thematic analysis used both an inductive and deductive approach. The deductive approach utilizing existing literature was most helpful in identifying more detailed codes of specific factors communicated relating to product attachment and product usage behavior. These included codes related to memories of persons, events, and places; self-expression/self-identity; pleasure/product enjoyment; irreplaceability (Mugge, 2007; Mugge et al., 2008; Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008), group affiliation (Mugge et al., 2008; Mugge, 2007); product utility; and product reliability (Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008). Unique factors communicated were added until a comprehensive list of psychological meaning, objective considerations, and behavior emerged. The higher-level themes that sought to organize collections of individual factors followed a more inductive approach guided by referencing the interview data. The transcripts were analyzed in a qualitative research software program (Atlas.ti) to allow observation of the frequency of communicated factors, rapid review and comparison of quotations within and between codes, and iteration of assigning unique codes to higher-level themes. Findings and initial identification of themes between the two researchers largely corresponded, and areas of unique observation were discussed for incorporation into the analysis.

>Results

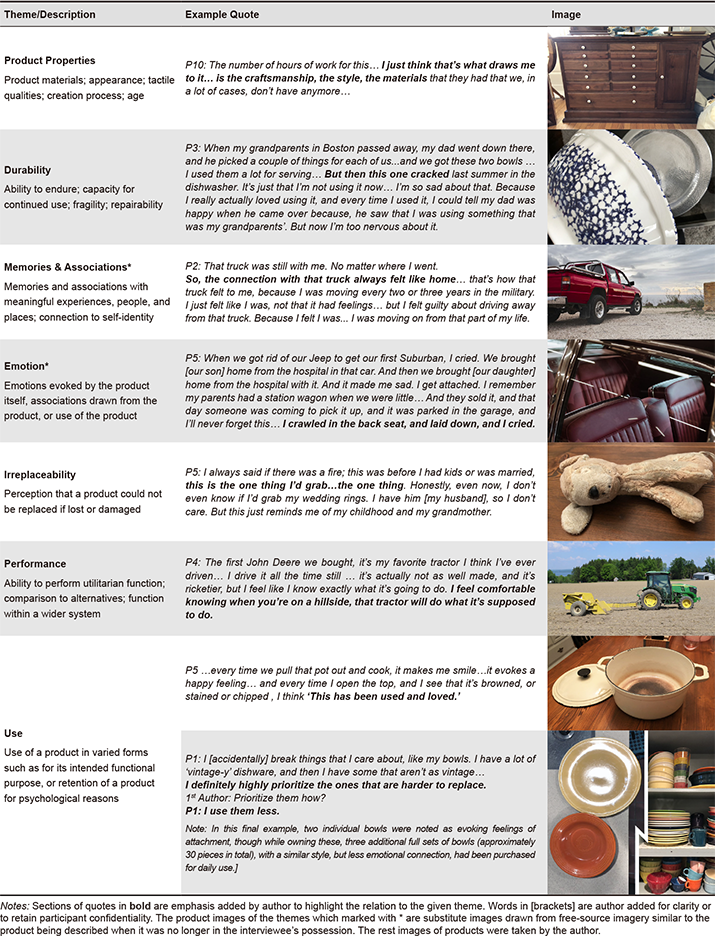

Working through multiple iterations of transcript review, coding, and conceptual organization, seven top-level themes emerged, which covered areas of consideration relative to product attachment and associated product usage behavior. The themes were Product Properties, Durability, Memory & Associations, Emotion, Irreplaceability, Performance, and Use. It should be noted that while the themes attempt to identify discrete areas of concern, the analysis suggests that, in practice, they were often communicated simultaneously as interrelated items. This observation mirrors that of Page (2014), who sought to apply qualitative interview data to five of the seven factors proposed by Schifferstein, & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim (2008), concluding, “The differentiation and boundaries between themes have been difficult to define, as many are interlinked and influential of one and other…, a number of sub-factors were found to be influential to how attachment developed according to each theme and could be used to form new and separate determinants of product attachment” (Page 2014, p. 280). An example from one interview in this study, referring to a specific lacrosse stick of a life-long athlete, is as follows:

1st Author: Have you ever used it [handmade wooden lacrosse stick] in a game?

P8: Not in a real game [Code – Passive Use; Theme – Use]. Because I don’t want... I mean, it would totally be fine. It just kind of weighs in the balance of... It’s a thing I’m going to have forever obviously [Code – Retention; Attachment], but do I really want to keep it in tip-top shape [Code -Damage and/or Wear; Theme – Durability]? Or should I use it [Code – Active Use; Theme – Use] because that’s what it’s meant for [Code – Intended Practical Function; Theme – Use]? It’s probably just the weight [Code – Perceived Relative Performance; Theme – Performance] honestly… the game’s so fast these days… I haven’t used it [Code – Passive Use; Theme – Use]. >I’m afraid to [Code – Fear; Theme – Emotion], but again, I probably should [Code – Expected Behavior; Theme – Use].

This dialogue suggests several overlapping and interconnected concerns following in quick succession as the interviewee communicates their understanding of one particular product. In spite of the interconnectedness, drawing from previous literature and new data from the interviews, the analysis aimed to convey a set of related yet distinct themes covering an overarching understanding of the attachment and product usage process. The seven themes are described below, and key examples from the interviews are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of qualitative themes, key quotes, and product examples drawn from the interviews.

Product Properties

The theme of Product Properties dealt with properties of the product’s physical nature, appearance, and the way it was made (e.g., the material qualities of the product, its age, creation process, and brand). Concerns here were also relevant to the product’s aesthetic attributes, such as visual appeal and tactile qualities (e.g., softness and warmth). They were often expressed in terms of the individual’s personal style or aims of cohesiveness of style across the products they owned.

Durability

The theme of Durability focused on a product’s capacity to sustain continued use over time. Concerns focused on the user’s perception of a product’s risks and potential damage should it be mishandled or continued to be used. This concern appeared to interact significantly with the material qualities of the product (e.g., ceramic, glass, wood) and the activities the product would be involved in during use. Durability seemed especially relevant to concerns over continued use of products perceived to be fragile and at risk of being damaged or lost through continued use.

Memories & Associations

The theme of Memories & Associations dealt with considerations of the product on a subjective level. The theme primarily focused on memories and associations between the product and other people, family members, connections to places, meaningful experiences, and self-identity. In these instances, the considerations were often unique to the individual expressing them and less readily observable without explanation due to their subjectivity. The product often appeared to serve as a form of connection and continuing reactivation of these particular meanings.

Emotion

Emotions were prevalent in the discussion of attached products and covered a range from positive to negative, mixed or conflicted. The types of positive emotions were varied and could be directed toward the product itself, activities enabled by the product, as well as the memories and associations evoked by the product (e.g., happiness, love, and comfort). While less prevalent than positive emotions, negative emotions were also reported (e.g., sadness, guilt, and fear). These emotions were often associated with loss, of the product itself, through damage from continued use, of an individual the product represented, or concern for these events transpiring. There was also discussion of mixed emotions. These emotions were often elicited due to conflicting concerns regarding a product (e.g., a desire to use it more often but fear of it becoming damaged). These feelings arose from associations generated by the product, often in relation to a significant individual who was no longer in the person’s life. The feelings were often represented by sentimentality, or dilemma.

Irreplaceability

The theme of Irreplaceability dealt with the connection individuals had with products, and how they perceived specific products to be unique or one-of-a-kind. Conversations often dealt with particular life experiences and important people connected to the product. Within this context was a discussion of the emotional implications if a product was to become damaged or lost. In these instances, the inability for an identical product to replace the one of attachment illuminated perceptions of irreplaceability.

Performance

The theme of Performance dealt with the functional qualities of the product under conditions of active use. The discussions centered around how well the product succeeded in providing the practical utility it was intended to deliver. Concerns about maintenance and repair needs to keep a product performing properly were also expressed. These discussions ranged from how an individual thought the item should perform, how it functioned compared to other products of the same type, and how the product performed within a wider ecosystem of interconnected products (e.g., compatibility of multiple electronic devices).

Use

The theme of Use focused on the various forms of interaction with products of attachment. These ranged from active physical interaction for utilitarian purposes to more psychological use to recall memories of experiences, places, and individuals. Instances of more passive use included when individuals had retained a product but ceased to use it for its utilitarian purpose. Reasons for this transition included concerns about product durability, performance, or irreplaceability. Modes of passive use included turning the product into a decorative item put on display to indefinite storage out of sight.

Incorporating the Findings into an Attachment-Behavior Conceptual Model

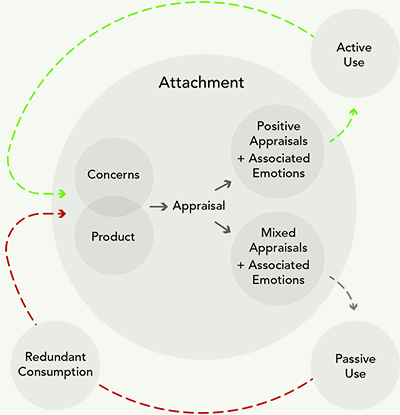

Following the development of themes that sought to organize groups of related individual factors, a systems mapping process was undertaken to examine how these groups related to one another as an interconnected system. This process is noted as being particularly appropriate for making explicit an observed set of relationships when analyzing complex areas of interest, and incorporates the visualization of causal loop diagrams (Meadows, 2008, Sedlacko et al., 2014), which here documented multiple stages of psychological and behavioral action occurring through time. As product attachment is noted as involving a continuing person-product relationship over time, this form of analysis was considered appropriate. Key products and supporting quotes that suggested the active and passive use pathways were mapped aimed at investigating the presence of an underlying process of attachment and behavior across the range of interviews, and potential for a generalized attachment-behavior model.

This systems mapping in conjunction with the thematic analysis sought to integrate the dual pathways of use presented in the initial hypothetical model (see Figure 2) and observed through product usage examples in the interviews. Returning to relevant literature, the model adapted and expanded on a basic model of appraisal and resultant emotion in product experience developed by Desmet and Hekkert (2007) as it helps describe how the users’ varying emotional responses (e.g., satisfaction or sadness) are shaped both by users’ concerns and a product’s relevant properties. We additionally focused on usage behavior as the next relevant layer of output.

The conceptual model visualized in Figure 4 is developed as a looped system because the interactive person-product relationship in the context of product attachment occurs and re-occurs over extended periods of time. This illuminates the continuing reappraisal over time that occurs due to changes relevant to the product (e.g., damage experienced during use, changing style trends), or changes relevant to concerns of the owner (e.g., a change in style preferences, relationships with other individuals, or developments in self-identity).

Figure 4. Attachment-behavior conceptual model.

The model pairs the user’s concerns as an interacting element with a product. The concerns may be goal-attainment (e.g., “I want to improve my cooking skills by using this kitchen knife.”) or personal preference (e.g., “I enjoy vintage kitchenware.”). In relation to the user’s concerns, the product contains inherent material qualities, functionality, durability, and other product-centric attributes. These varying concerns and related product attributes are each appraised by the user and appear to range from negative to mixed and overall positive assessments.

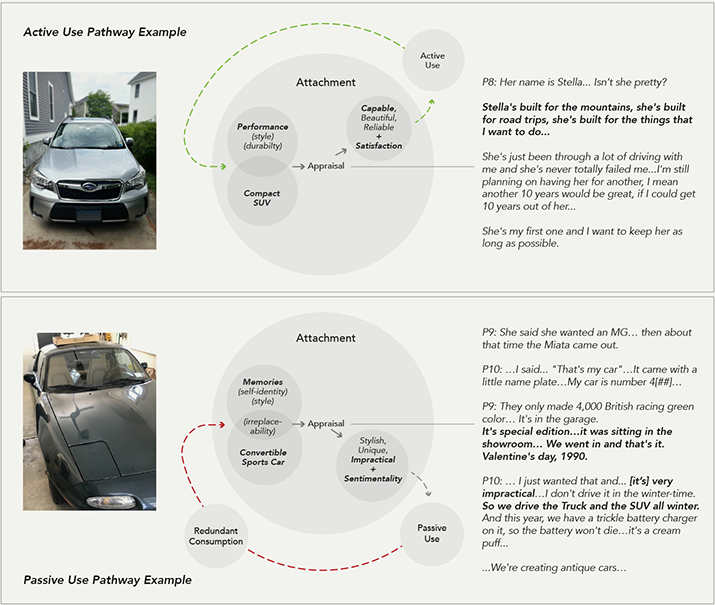

A key observation throughout the interviews was alignment or disparity in the various appraisals of specific product attributes and user concerns. In instances where the appraisal patterns appeared to be at least neutral to positive overall (e.g., adequate performance, durability, aesthetic qualities, and positive associations), active use was more common. Conversely, when negative appraisals were included in the process, the use pattern became more passive and the potential for redundant consumption appeared more likely. Examples from the interviews included enjoying items given from a family member but having concerns about the product’s fragility, unfavorable style, or inadequate performance. In these instances, the product was often retained but transitioned to a more decorative object or stored away. In these cases, redundant consumption of similar products was more common to fulfill the practical functionality of the product. Below are examples from separate interviews centered on the same product type of an automobile but with differing patterns of appraisals and use to further illustrate this point. Note the top pathway of active use, where the interviewee expresses a range of concerns, and the product is appraised as adequate or positive for each concern. Conversely, the car on the bottom is noted favorably relative to several concerns, but the mention of it being impractical to drive in the winter introduced a key negative appraisal. This led to diminished use and additional vehicles necessary to fulfill personal transportation needs. (See Figure 5).

Figure 5. Product examples on attachment behavior pathways.

Given that the results of Study 1 supported the hypothesized dual pathways of active and passive product use, more detailed evidence was sought in Study 2 to better understand which factors of attachment might have greater influence in steering behavior to the different pathways of product use and consumption behavior.

Study 2: Effects of Product Attachment Factors on Sustainable Product Usage Behaviors

The purpose of Study 2 was to quantitatively support and refine the qualitative insights drawn from Study 1, including identifying (1) the relative strength of individual factors in fostering product attachment and (2) which variables may play a role in the different pathways of product use. It was hypothesized that individual factors of attachment would lead to either more active or more passive forms of use with attached products. It was also hypothesized that more passive use of an attached product would be associated with redundant product consumption. An online questionnaire study was conducted to test these hypotheses.

Method

Questionnaire and Variables

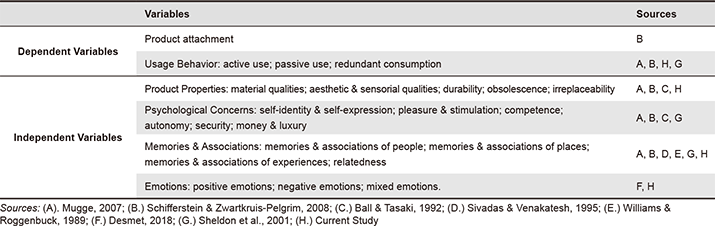

The development of the questionnaire followed both a top-down and bottom-up approach seeking to synthesize previous work around product attachment and key insights from the thematic analysis generated in Study 1. The intended dependent variables (DVs) of interest were attachment, active use, passive use, and redundant consumption. The intended independent variables (IVs) related to areas of product properties, psychological concerns, memories & associations, and emotions. Table 2 outlines the variable categories and intended IV’s of interest.

Table 2. Intended Variables and related literature sources.

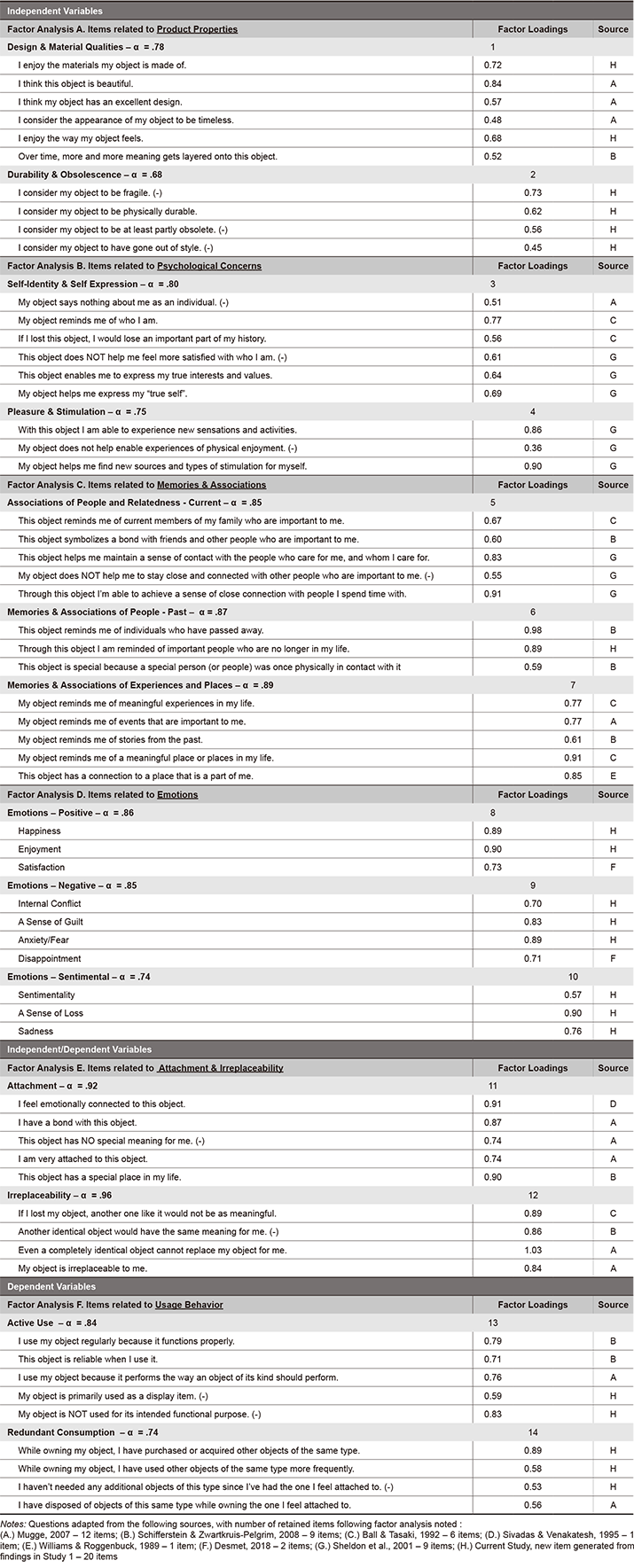

Seven existing scales and surveys were referenced seeking established questions used in related past studies. The referenced sources included areas of focus on product attachment (Mugge, 2007; Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008), attachment in consumer behavior (Ball & Tasaki, 1992), object attachment and self-identity (Sivadas & Venkatesh, 1995), place attachment (Williams & Roggenbuck, 1989), and emotional responses to product interaction (Desmet, 2018). Psychological concerns expressed in Study 1 were represented based on an established taxonomy of fundamental psychological needs (Sheldon et al., 2001): relatedness, pleasure & stimulation, competence, money & luxury, security, and self-esteem. Finally, items were created by the authors to address variables, including active use, passive use, redundant consumption, and specific emotions identified in Study 1 that were not present in the previously referenced literature. A total of 110 questions were developed with demographic questions, attached product selection, and explanations related to selecting a personal product of attachment for consideration. Ninety-one questions were aimed at capturing the variables related to attachment and usage behavior. Items were presented on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 as strongly disagree to 7 as strongly agree. The final list of questions used in the analysis can be seen in Table 3. (For a PDF version of the online survey as it appeared to participants, see http://mdtl.human.cornell.edu/kowalski-2022-ijd-survey)

Table 3. Factor analysis results. Factor analyses were performed with principal axis factoring, and Promax rotation with Kaiser normalization. Factors extracted with eigenvalues greater than 1. Pattern matrix factor loadings reported. A (-) denotes a reverse-coded item. All cross-loadings below |0.30|.

Participants

The survey was administered through the Amazon Mechanical Turk online platform. Criteria for respondent selection included residing in the United States, having a 98% minimum task approval rating on the platform, at least 500 completed tasks, and Amazon Masters designation. The Masters designation is assigned to individuals who have shown consistently high approval ratings on assignments previously completed within the system. Collecting data through this online platform has been found to be reliable and efficient while reducing threats to internal validity relative to other recruitment methods (Paolacci et al., 2010). Participants were paid $2.50 for their participation with a completed survey and were told the survey would take approximately 10-15 minutes to complete, representing an approximate hourly rate of $12 per hour. A total of N=221 surveys were completed in full (113 male, 108 female), with an additional 27 left incomplete and eliminated (completion rate: 89%). The average survey time was 11.4 minutes. Participant ages ranged from 21 to 74 years old (M=43, SD=11.6).

Procedure

Along with a prompt to consider selecting a specific product possession to which the participant felt emotional attachment and intended to retain for a long period of time, a visual collage was presented to aid in consideration of a wide range of potential product types. Care was taken to select images that conveyed a range of items at differing physical scales, analog and digital, made of natural materials and synthetic materials, vintage and modern, used individually or in groups, enablers of activity, and items carried or worn on the body (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Image-based prompt for product selection in the survey process.

Participants were then asked to note the product possession they had selected for consideration when answering the survey questions, along with a brief description of their reasoning for feeling attached. This allowed the researchers to observe the types of products selected by participants, as well as sensitize them to the area of concern for the questionnaire. Participants were also offered the opportunity to upload an image of their attached product at the end of the survey.

Results

Products Selected by Participants

From the questionnaire, a total of 221 products were mentioned, one for each participant. The selected products were diverse and included: furniture—bookcase, dresser, homemade chest, dining table; sporting equipment—golf clubs, skydiving gear, shotgun, tent, hand-carved bow, fishing rod and reel owned since a child; cooking devices—wok pan, kitchen-aid mixer, rolling pin, chef’s knives; vehicles—mountain bike, car, sailboat, motorcycle; electronic devices—video game systems, fit-bit, digital camera; garments and accessories—kimono wrap, a ripped shirt, wristwatch, purse; tools—sewing machine, grandfather’s hammer, letter opener; and various other items such as dishes, a travel journal, acoustic guitar, blanket, and vintage radio. Nearly all the items selected fit the desired description seeking consideration of a product with a practical utilitarian purpose, whether or not the item was still in use for that purpose. Approximately 5% of surveys appeared to focus on items that may be thought of as serving more decorative or aesthetic concerns, such as figurines, jewelry, or artwork. These items were retained because they still represented a relevant environmental impact through their production, consumption, and use.

Adequacy of Individual Survey Questions

As the questions in the survey were drawn from several literature sources, and also included new items developed following the analysis in Study 1, it was essential to investigate whether survey respondents appeared to understand and interpret questions consistently. For this, exploratory factor analysis was conducted, followed by internal consistency checks through Cronbach’s alpha calculations. The factor analysis was performed in stages, utilizing the previously described top-level categories of product properties, psychological concerns, memories and associations, emotions, and product usage behavior. The questions aimed at capturing product attachment and irreplaceability were analyzed together to confirm that these related factors were interpreted as distinct constructs. Question items that had factor loadings of |0.45| and above on one factor, with cross-loadings at |0.30| and below, were retained on a factor, and those that fell outside that range were removed (Hair et al., 2010). This aimed to retain only questions that displayed evidence of convergent validity within individual variables and discriminant validity between variables in the analysis (Raubenheimer, 2004). Factors were analyzed within SPSS V.26 using a principal axis extraction method and Promax rotation. The Promax rotation was selected as the potential individual factors within each top-level category were theoretically expected to be correlated, thus making an oblique rotation method appropriate (Finch, 2006). Of the original 91 questions, 60 representing 14 variables of interest met the criteria and were retained for further analysis, the rest being removed. Next, Cronbach’s alpha values were calculated to see how consistently individual questions were interpreted within these factor groupings. Following this, participant scores for the questions within each variable were averaged to create composite variables for the next stage of analysis (Hair et al., 2010). Details of extracted factors, retained question items, factor loadings, and internal consistency are shown in Table 3. For an expanded version of the factor analysis table that includes the questions omitted for further analysis, please see http://mdtl.human.cornell.edu/kowalski-2022-ijd-table3.

Factor Analysis Discussion

During the factor analysis, an exception was made to the above-stated criteria for one item in the pleasure & stimulation factor with a loading of 0.36. It was retained as being adapted from an existing validated scale (Sheldon et al., 2001) and identified as an influencing factor of attachment in previous research (Mugge, 2007; Mugge et al., 2010; Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008, Page, 2014). Additionally, during the internal consistency check, the durability/obsolescence factor had the lowest alpha value of the identified factors (a = 0.68). This value was slightly below the generally recommended lower-end level of 0.70 (Nunnally, 1975), though Hair et al. (2010) suggest a lower limit of 0.60 as being acceptable in exploratory work. The questions in this area addressed the physical durability of a product, obsolescence, and interpretation of whether a product had gone out of style. While these items may appear somewhat varied, previous research (e.g., Schallmo et al., 2012) has defined a holistic conception of obsolescence on a spectrum from objective physical durability, to issues of relative performance given newer alternatives, to subjective concerns related to obsolescence based on perceived style. In this way, the construct may be thought of as including the ability of a product to endure in a continued person-product relationship on both objective and subjective grounds. This also draws connections to the related research on emotionally durable design (Chapman, 2009; Chapman, 2015; Haines-Gadd et al., 2018), which has investigated both emotional and physical durability holistically. Additionally, Study 1 included several cases in which users discussed both physical durability and concerns about dated style, or a form of obsolescence based on style. One example is: “Then we recovered the chairs… the old leather just cracked, and then the front couch it was a bright turquoise, like 1960s style, very turquoise… so we also had to re-cover that” (P3). As the alpha level was near to adequate, and the survey items represented a significant area of concern identified in the qualitative research study, it was retained as a factor for further analysis with the acknowledged limitation.

As a main area of interest, passive use failed to develop as an adequate factor during the analysis process. Two items that focused on protective behavior, “I am very careful about my object” and “I prefer to keep my object safe rather than risk it getting damaged or lost” did load onto a separate factor. Despite this, as a minimum of three items per factor is recommended in factor analysis to adequately represent a construct (Hair et al., 2010; Watkins, 2018), passive use was removed from further analysis. While active and passive use were initially conceived as distinct behavioral concepts, it could be possible this behavior is interpreted on a spectrum, with a single conception of use increasing or decreasing relative to the product’s intended use. Since active use did load with a five-item factor and an alpha of .84, it was determined to move forward with active use as the sole factor and perform the analyses to identify whether there were factors that led active use to increase or decrease, respectively.

Relationships between Product Attachment, Active Use, and Redundant Consumption

We investigated which variables (i.e., IVs) contributed to increases or decreases in attachment, active use, and redundant consumption (i.e., DVs) by running multiple regressions. Variables from the groups of product properties, psychological concerns, memories & associations, and emotions served as IVs. IVs that showed standardized beta coefficients at or above .10 and significance levels of p ≤ .05 were retained, and those not meeting the criteria were removed from the model.

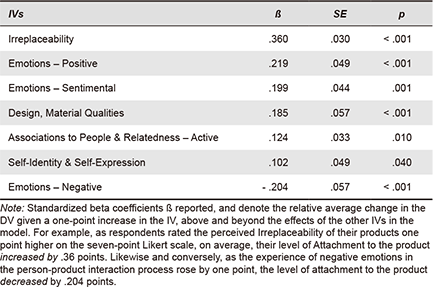

Influencing Factors of Product Attachment

Seven factors contributed to explaining 64% of the variance in attachment. Attachment was most associated with the perceived irreplaceability of a product (ß=.360), positive emotions (ß=.219), and sentimental emotions (ß=.199). The design and material qualities of a product, its ability to contribute to relatedness with others, and its connection to self-identity and self-expression were also identified as significant factors of attachment, in line with the inter-connected central components of concerns and product illustrated at the center of the generalized attachment-behavior model developed in Study 1. Attachment showed a negative coefficient for negative emotions (ß= -.204), implying the presence of negative emotions decreases attachment levels. The complete list of factors and statistical values from the regression analysis are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Product attachment (DV) regression analysis results (R² = .64).

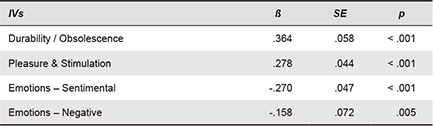

Influencing Factors of Active Use

A four-factor model that explained 47% of the variance in active use was identified. Aligning with the earlier discussion of the potential for factors that may promote or reduce active use of a product, two factors were identified with positive beta coefficients, suggesting a promoting of active use of a product, and two were identified with negative coefficients, suggesting a reduction of active use. The primary factor increasing active use was durability / obsolescence (ß=.364). This suggests that more active use of a product occurs as people perceive their products as being more physically durable and resistant to becoming obsolete. The second factor was pleasure & stimulation (ß=.278), suggesting that higher levels of pleasure and stimulation in product use are associated with increased active use of the product. Conversely, two factors were found to have a negative relationship with active use: sentimental emotions (ß= -.270) and negative emotions (ß= -.158). This finding suggests that as an individual experiences higher levels of sentimental or negative emotions associated with a product, they are less likely to actively use it. The complete list of factors and statistical values from the regression analysis are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Active use (DV) regression analysis result (R² = .47).

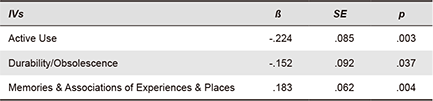

Influencing Factors of Redundant Consumption

A three-factor model was identified that explained 16% of the variance in redundant consumption. Redundant consumption was shown to have a negative relationship with active use, suggesting that as a product is used less for its practical function, there is a need for additional consumption of similar products. Durability/obsolescence showed the same direction of relationship, suggesting that as products are perceived as being less durable and resistant to becoming obsolete, the more likely redundant consumption of similar products occurs. The psychological variable of memories & associations of experiences and places, in contrast, showed a positive relationship with redundant consumption. The complete list of factors and statistical values from the regression analysis are shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Redundant consumption (DV) regression analysis results (R² = .16).

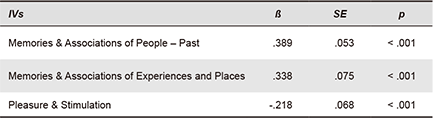

Additional Analysis—Irreplaceability

As irreplaceability showed the most significant relationship influencing attachment (ß=.360), and previous literature has stressed its importance, an additional regression analysis was performed to identify if factors present in the current study would be related to irreplaceability as a DV. Three factors were identified that explained 45% of the variance in irreplaceability: products that elicited memories & associations of people in a past sense (ß=.389) (e.g., memories of individuals who had passed away), memories & associations of experiences and places (ß=.338), and pleasure & stimulation with a negative relationship (ß= -.218). This third finding suggests pleasure and stimulation in person-product interaction occurs less as items are perceived to be more irreplaceable. The complete list of factors and statistical values from the regression analysis are shown in Table 7.

Table 7. Irreplaceability (DV) regression table (R² = .45).

Finally, the factor of sentimental emotions, which was shown to be related to increased attachment but also reductions in active use, was analyzed further as a DV. Memories and associations of people from the past (ß = 0.68) were shown to account for 46% of the variance in sentimental emotions. As discussed below, these findings draw a further connection between the identified sub-factors of irreplaceability and less sustainable product usage behaviors.

Brief Discussion of Study 2 Findings

Using multiple regression analysis, Study 2 differentiated (1) factors associated with increasing product attachment, (2) factors associated with active use of products, and (3) factors associated with redundant product consumption. In identifying the relative strength of each factor, the results revealed that attachment was most highly associated with the perceived irreplaceability of a product, followed by positive emotions and sentimental emotions, factors related to a product’s design and material qualities, its contribution to relating with others, and its connection to self-identity and expression.

A noteworthy finding was that although irreplaceability was the most prominent factor contributing to attachment, a relationship with less sustainable behavioral outcomes was illuminated. Regression analysis of the factor of irreplaceability revealed three related factors. The first two factors, memories and associations of important people from the past, as well as memories of meaningful experiences and places, were shown to increase the perceived irreplaceability of a product while also showing connections to decreased product use, as well as increased redundant product consumption. The identification here of these two memory-related factors directly aligns with the previous investigation into factors of the construct of irreplaceability, termed temporal indexicality (related to memories of a past time), and corporal indexicality (related to memories of a person) (Grayson & Shulman, 2000). The third factor related to irreplaceability here was pleasure and stimulation, but showing a negative relationship. This finding suggests that as a product is considered more irreplaceable, pleasure and stimulation in product interaction processes occur less often.

Previous research has suggested designers should focus on increasing irreplaceability to stimulate more sustainable product consumption (e.g., Mugge et al., 2005, 2008; Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008), including suggesting “…the critical importance of context when designing for emotional attachment, and the real end game: perceived irreplaceability” (Armstrong, Niinimäki, and Lang 2016). However, our results do not appear to support that recommendation. If the design intention is more environmentally sustainable product consumption behavior, increased levels of perceived irreplaceability might have the opposite of this intended effect.

The abovementioned findings are noteworthy as the factor of pleasure and stimulation was found to be statistically significant in increasing active use of a product, and active use reduces the need for further product consumption. These results appear to align with previous research that identified pleasure as a mediator connecting the relationship between the utility of a product and attachment to that product (Mugge, Schifferstein, & Schoormans, 2010). Also, research in the field of fashion design has suggested pleasure as a critical factor of continued use of clothing items, while attachment deriving from memories leads to reduced use and storage of garments as mementos (Niinimäki & Armstrong, 2013; Armstrong, Niinimäki, and Lang 2016). Our results also align with the theoretical and empirical work developed by Corral-Verdugo et al. (2011, 2012) in positive psychology, linking the pleasure and subjective well-being of individuals with more sustainable behavioral outcomes in a potentially mutually beneficial relationship.

As individuals appraised their products as being more durable and resistant to becoming obsolete, active use further increased. In contrast, as a product was considered less durable or resistant to becoming obsolete, further redundant product consumption occurred. These findings further illuminate the critical role of durability in product use and consumer behavior for extending product lifetimes and reducing waste, as discussed in the EPAs (2018) recommendations. These results support the initial hypothesis of varying pathways of behavior dependent on the presence of different objective and subjective factors in the attachment process and support the findings from Study 1 with detailed quantitative insights. The resulting insights are further discussed in conjunction with the findings from Study 1 in the following section.

General Discussion and Conclusion

Summary and Contributions

This work advances the literature by demonstrating that: (1) the results from both studies support the initial hypothesis that products of attachment can exhibit varied pathways of use, with some products continuing to be used for their practical function, and others retained primarily for their psychological value; (2) decreases of active use of products for their practical function was connected to increasing redundant product consumption; and (3) irreplaceability, the primary factor that contributed to increasing levels of attachment, was also associated with less sustainable product consumption behavior, in contrast to assumptions in previous work.

As attachment involves multiple influencing factors, each presenting different behavioral implications and relevance to the product design process, it is crucial to develop a more detailed and nuanced understanding of how the factors might influence users’ experiences and behaviors with the product of attachment. For example, while aiming to facilitate product attachment, designing for pleasure and stimulation may be a fundamentally different challenge than designing to promote relatedness or self-identity. Although the existing literature presents an array of design strategies addressing the wide range of factors that may encourage attachment (e.g., Haines-Gadd et al., 2018; or Wu et al., 2021), there appears to be limited consideration of the broader behavioral implications for increasing attachment and leaves a lack of clarity on the impact on ongoing product use and consumption processes. Thus, using product attachment to foster greater sustainability needs to rest on a more systematic foundation that also considers usage behavior and related product consumption over time. In our view, diverse design strategies to foster increased levels of attachment must also help designers be aware of how they can avoid unintended behavioral consequences (e.g., retaining products solely for their psychological associations), while aiming for their intended impact (i.e., more positive and sustainable person-product relationships).

Implications for the Practice of Design for Product Attachment

This paper has identified factors that can promote product retention through increased attachment and factors relevant to ongoing active product use and redundant product consumption patterns. Here we discuss the implications for design practice at several stages of the attachment and behavior context and what appears most relevant and promising for the design process.

A More Holistic Approach

To better position designers to achieve goals aimed at more sustainable and enduring person-product relationships, we propose that the attachment-behavior model developed in Study 1 (see Figures 4 and 5) and supported with detailed findings in Study 2 can serve two primary purposes. The first is as a framing device (Dorst, 2015) to guide initial user research and interviews around current practical and psychological needs being addressed by a specified product. This would enable designers to investigate the quality of the emotional relationship users currently have with the product and how product properties and users’ concerns interact to affect both the person-product relationship and the associated behavioral usage patterns. While the content within the model (Figure 5) may change based on the specific product, user, or situation being analyzed, the proposed attachment process (i.e., appraisals of product properties relative to users’ concerns) and resulting behavioral pathways are expected to remain consistent. This can enable designers to systematically understand how their intended users could become attached to a particular product, how this could affect their active or passive usage behavior, and which factors in the process may function as key leverage points on the pathway to more sustainable practices. Therefore, the structured overview enabled by the model could help designers elucidate “deeper issues and needs that are at play in the problem situation” (Dorst, 2015, p. 26).

The second role would be as a source of inspiration in early concept development processes, helping designers consider the broader impact of emotional connections with products. This could be relevant for changes or updates to existing products or for creating new products and services to address psychological and practical needs along a pathway of more environmentally sustainable behavior. Various relevant factors identified in Study 2 can serve to illuminate a range of potential design directions, from more aesthetic and material attributes of products to more experience-driven design. In addition, as was observed in cases in Study 1, where several factors were interrelated, multiple directions can likely be combined. Returning to the car example in Figure 5 from Study 1, the participant appraised their vehicle as being aesthetically beautiful, capable of performing across a wide range of pleasurable and stimulating adventures, and reliable over a long period of time. The interaction of the product’s properties successfully delivering on these key user concerns led to enjoyment, satisfaction, and a desire for a continued active relationship for many years to come.

By definition, product attachment involves a subjective person-product relationship, and the meaning of a product is constructed and solidified by unique personal narratives over time (Csikszentmihalyi & Rochberg-Halton, 1981). As such, an important opportunity for design is continuing to find ways to integrate users’ agency in the creation of the product’s meaning, from product creation, through to the design of activities and services such as maintenance, repair, or modification that further extend both physical and psychological aspects of the product over time. Since this process might require the user’s attention, commitment, and aesthetic evaluation, we suggest that the users’ individual preferences, strengths, skills, resources (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Sung & Yoon, 2021) and the personal fit with the experiences (Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013) should be taken into consideration from product conception through to specific engagements during the product ownership phase.

Design Opportunity 1

Promoting Product Retention through Increased Attachment

Study 2 identified four factors that promoted feelings of product attachment, which did not entail unfavorable consequences at the product use and consumption stages. These factors that promote attachment and thus can lead to beneficial product retention are, when a product is considered to be: (1) promoting positive emotions (e.g., enjoyment, and satisfaction); (2) possessing favorable design and material qualities (e.g., aesthetic qualities of a product, a timeless design); (3) promoting relatedness and bonding with other people; and (4) promoting an individual’s self-identity and self-expression. These factors represent core competencies of designers and, when executed to the satisfaction of end users, can increase the likelihood of an emotional connection building over time.

Design Opportunity 2

Promoting Active Use of Products of Attachment

Study 2 also identified two key factors that promote active use of products of attachment for their functional purpose and are also directly relevant to the design process. These factors were when a product was perceived as being durable and resistant to becoming obsolete, as well as the ability of a product to promote pleasurable and stimulating experiences. Again, these two factors are directly relevant to the product design process and highlight the importance of taking a combined approach to both the objective and subjective factors of concern for users when seeking to promote lengthened product lifetimes. Design efforts here may encompass the use of materials that are physically durable and possess the ability to age gracefully, an approach promoted in earlier related research (e.g., Chapman, 2009; Haines-Gadd et al., 2018). The promotion of pleasurable and stimulating experiences and activities facilitated through products also highlights the importance of user experience design strategies that seek to promote a more engaging and positive experience-driven design approach, as it also contains related environmental sustainability benefits through continued active product use (Desmet & Hassenzahl, 2012; Boess & Pohlmeyer, 2016).

In contrast to the above, the factor of sentimental emotions was also shown to increase product attachment, yet at the use stage was shown to be associated with decreasing use of a product. The analysis in Study 2 showed that sentimental emotions derived mainly from memories and associations with important people from the past. This concern may be less directly relevant to the new product design process. However, it may suggest reflection for designs commonly given as gifts or product sale/reuse systems such as second-hand shops and online community marketplaces.

Design Opportunity 3

Avoiding Redundant Product Consumption in the Attachment Process

Our results showed that when products continue to be actively used for their practical function, consumers avoid unnecessary redundant consumption, and thus active product use has a direct connection to lowering ongoing consumption rates. Conversely, products related to memories and associations of places and experiences showed a connection to increasing levels of redundant product consumption. The memory-related factors of irreplaceability again appear on the fringes of the relevant scope of the traditional design process and, as discussed, are not desirable to promote when more sustainable behavioral outcomes are being sought. With this in mind, design efforts such as creating souvenirs, mementos, or a product attribute meant to capture memories of specific experiences in people’s lives may need to be approached with more attention (for an overview in this area, see Casais et al., 2018). In this scenario, to reduce the unintended consequences associated with perceptions of irreplaceability, designers could consider whether attachment to objects intended to recall experiences and places may be possible by emphasizing a different factor of attachment. For example, if a product incorporating a practical function acquired on a trip with friends or family could promote feelings of relatedness, self-identity and expression, rather than solely memorializing the place or experience, there may be the combined outcome of increased attachment and sustainability benefits.

Extending the discussion of the concept of irreplaceability beyond the factors of memories and associations identified in this study, questions arise on whether additional potential sub-factors more relevant to the design process aimed at creating unique products may be at risk for less sustainable product consumption behaviors. In this line of thought, an emphasis on the design of limited-edition releases (e.g., as shown in the garaged sports car example in Study 1), personalization that emphasizes sentimental memories, or beautiful but scarce materials, might be considered with caution based on the results presented here. These latter approaches, while potentially being similarly capable of stimulating product attachment (e.g., Teichmann et al., 2016), may inadvertently create products perceived as so unique as to be nearly irreplaceable. These strategies, which can stimulate the perception of rarity and are commonly shared among the design and advertising of luxury consumer products and brands (Kapferer, 2012), may have connections to less frequent product usage and increased consumption, in a manner similar to irreplaceability shown here. Study 1 revealed occasional signs of product category and/or brand involvement, phenomena which are noted as being distinct but related to product attachment (Kleine & Baker, 2004). In these instances, a parallel track of collecting and consumption with items such as sneakers, dishware, and sporting equipment appeared to share connections to an individual product of attachment. While these ideas of potentially less sustainable consumption behavior related to product uniqueness or qualitative rarity (Kapferer, 2012) are plausible, further study to more fully explore the construct of irreplaceability and behavioral outcomes is needed.

Limitations and Opportunities for Future Research

Following the discussion above, several additional areas explored in this paper are worthy of further inquiry. While variation in demographic variables was sought in Study 1, the identified participants represent a relatively narrow range of income levels, geography, and racial backgrounds. Although the qualitative approach of Study 1 enabled us to provide rich and in-depth insights into the relationship between product attachment and sustainable usage behavior, further research in this area would benefit from interviewing a broader sample of individuals based on these and additional areas of demographic diversity.

During the factor analysis in Study 2, several factors adapted from fundamental psychological needs (Sheldon et al., 2001) did not hold together with adequate factor loadings and alpha values. For some of these intended factors, discrepancies in scoring on reverse-worded and reverse-scored items in the analysis might suggest some participants missed the reversed wording (Woods, 2006). As each of these factors had only three items present, deviation in any one of the items would yield inadequate results. As these items, including concerns of money and luxury and security, had not been identified as significant factors in previous research on product attachment, they were eliminated from further analysis. Future studies which seek to identify additional variables need to be undertaken to deepen our understanding of the causality of product attachment in the context of long-term sustainable behavior.

This paper sought to identify patterns of behavior in relation to product attachment without being restricted to a specific product type. Previous research has taken a variety of approaches from this perspective, including seeking broad diversity in products for consideration (e.g., Odom et al., 2009. Page, 2014), pre-specified product categories (e.g., lamps, clocks, cars, and ornaments; Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008), or individual product types (e.g., couches, Ko et al., 2015). These studies tend to show general consistency in factors of attachment, though variation in the relative strength of the factors based on product category (Schifferstein & Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, 2008). Relevant literature has also suggested that individuals give varying levels of attention to different areas of concern when evaluating differing product categories (e.g., cars, entertainment products, coffee makers, and domestic appliances; Jordan & Persson, 2007). Future research could investigate whether differing strengths in factors of attachment by product type might influence the pathways of product use and consumption behavior. Additionally, related research on clothing items in a fashion context reported variation in determinants of attachment based on length of ownership, though still showed significantly different averages between specific clothing types (Niinimäki & Armstrong, 2013). Given the goal of identifying patterns of usage behavior that encompass diverse product types, length of ownership was not included as a variable in this paper because it would vary significantly between product types and likely be spurious for comparison and analysis across categories. Future research that emphasizes research within a specific product category may consider integrating length of ownership as a variable of attachment and associated usage patterns.

Further considering the discussion of the findings for design practice, we would also like to note that the proposed model and the effects of influencing factors presented in this paper should not be seen or used simply as a formula or recipe. Product attachment is a rich and complex phenomenon, influenced by various factors identified in this study, and likely more still to be detailed further in the future. While some of the identified factors may appear to be straightforward in their relevance to the design process (i.e., factors of product properties), others may be more elusive (i.e., memories and associations) and require designers to continually consider their intended audience for gaining rich insights through detailed user research and other more interactive forms of co-creation. In this way, designers can stand on firmer ground when aiming to create tangible environmental benefits in the world through the pathway of more subjective concerns and usage behavior. See Sanders and Stappers (2012) for a comprehensive discussion on related co-creation methods and tools.

Conclusion

Product attachment, as an emotional connection to a specific product, has been shown to stimulate product retention, though the actual practical use of these products has been less examined. This paper presented a combined qualitative and quantitative investigation to contribute theoretical knowledge and empirical evidence on product attachment, addressing a limitation discussed in previous studies. As previous research has suggested product attachment could lead to more environmentally sustainable product consumption behavior, evidence was sought at the use and consumption phases to provide a more holistic understanding of behavior in this context. This work contributes a new strand to the body of research on product attachment and design for sustainability by providing new insights into the multifaceted factors of product attachment and their varied relationships with more environmentally sustainable product usage behaviors.