Briefing Beyond Documentation: An Interview Study on Industrial Design Consulting Practices in Finland

Seungho Park-Lee* and Oscar Person

School of Arts, Design and Architecture, Aalto University, Helsinki, Finland

Effective practices for briefing and sales represent a prime concern for design consultants in settling the scope of their work in projects. In order to understand this process, we undertook an inductive thematic analysis of interviews with, and documents collected from, 19 industrial design consultants in Finland. In analysing the ways in which the consultants go about settling briefs for new projects with clients, we unravel how briefing and sales are entwined in design consulting and how this impacts the practices of consultants. We found the entwinement between briefing and sales in design consulting produces a discontinuity in the briefing process subsequent to the commissioning of a project. Furthermore, the broader professional context of briefing and sales in design consulting involves uncertainties about the scope and outcome of design projects and the perceived readiness of clients to work with design. The consultants adapted their briefing practices to cope with and mitigate such challenges. We discerned three distinct types of adapted practices for briefing and sales—customised communication, codified conducts, and productised services—and go on to describe how the consultants used these practices to bridge uncertainties for clients and prevent challenges before projects are commissioned.

Keywords – Briefing, Design Consulting, Design Practice, Design Process, Design Sales, Reflective Practice.

Relevance to Design Practice – Novice designers can use the reports of the consultants in learning to work with clients and in internalising the practices for briefing and sales. Experienced designers can use the distinguished practices as a benchmark in evaluating and systematising their current consulting practices as well as devising new ones.

Citation: Park-Lee, S., & Person, O. (2018). Briefing beyond documentation: An interview study on industrial design consulting practices in Finland. International Journal of Design, 12(3), 73-91.

Received March 27, 2017; Accepted April 12, 2018; Published December 31, 2018.

Copyright: © 2018 Park-Lee & Person. Copyright for this article is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the International Journal of Design. All journal content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License. By virtue of their appearance in this open-access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

*Corresponding Author: seungho.p.lee@gmail.com

Seungho Park-Lee is a doctoral candidate in the School of Arts, Design and Architecture, Aalto University. His research explores briefing in various domains for design, such as design consulting and public procurement. He founded Design for Government course under Creative Sustainability master’s programme at Aalto University in 2013. He has earlier worked for the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra, as well as design consultancies in Helsinki and Seoul.

Oscar Person is an assistant professor in design integration in the School of Arts, Design and Architecture, Aalto University. His research interests range from the ways organizations acquire capabilities in design to the application of design in development processes, with a special interest in the expressive nature of designers’ work. He has earlier published in, among others, Design Issues, Design Management Journal, Design Studies, International Journal of Design and the Design Journal.

Introduction

The specific phases and outcomes of design projects are often open-ended and subject to change. However, design consultants are often pressured to predict the full scope of projects upfront when securing commissions. The situation is complicated by the fact that design consultants often have only partial insights into the processes, challenges and operations of clients’ businesses at the pre-project phase or the early phase of a project (e.g., Hakatie & Ryynänen, 2007, pp. 42-44). Establishing effective practices for briefing and sales, therefore, represents a prime concern for design consultants in settling the scope of their work in projects.

This paper reports on a study of the professional context of industrial design consulting in Finland and the practices of consultants in settling briefs for projects and securing commissions from clients. To date, a number of practical guidelines and recommendations have been published to aid designers and managers in formulating and managing briefs in different fields of design, including architecture (e.g., Blyth & Worthington, 2001; Cox & Hamilton, 1995), visual communication and advertising (e.g., Morrison, Knox, Ellis, & Pringle, 2011) and design management (e.g., Phillips, 2004). Focused research studies have addressed the real-life briefing practices of designers in more regulated fields of design, such as architecture and civil engineering (e.g., Bendixen & Koch, 2007; Luck, Haenlein, & Bright, 2001; Ryd, 2004; Ryd & Fristedt, 2007). Briefing in other design fields has received sporadic research attention through studies on problem framing (e.g., Dorst & Cross, 2001; Hey, Joyce, & Beckman, 2007; Paton & Dorst, 2011), or requirements elicitation and documentation (e.g., Haug, 2015; Wild, McMahon, Darlington, Liu, & Culley, 2010). Studies on client-designer relationships indirectly address briefing by studying how client companies work with and manage external designers (e.g., Bruce & Morris, 1994; Hakatie & Ryynänen, 2007) or how client-design consultant relationships are established and maintained (e.g., Bruce & Docherty, 1993). The reported study adds to the past guidelines and research efforts by providing a focused empirical perspective on the professional context of briefing in industrial design consulting and the practices used by consultants in settling the brief for new projects with clients.

By studying briefing beyond problem framing and answering the call for studies on the “meta-activities” design consultants engage in while formulating briefs for projects (Paton & Dorst, 2011, p. 575), we provide insights into, and practical guidance for, how industrial design consultants structure interactions with clients during briefing and sales prior to project commission. Through an inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, pp. 83-84) of interviews with and documents collected from 19 experienced industrial design consultants in Finland, we identify how briefing and sales are entwined during this pre-project phase of industrial design consulting and the impact of this on the interactions between clients and design consultants. We found that consultants engage with briefing and sales simultaneously, which presents challenges for settling effective briefs with potential clients. Moreover, we argue that the entwinement limits the possibilities for design consultants to iterate the initial brief throughout projects, as often recommended in literature (e.g., Blyth & Worthington, 2001; Phillips, 2004; Ryd, 2004). We note that the broader professional context of briefing and sales in design consulting involves uncertainties about the scope and outcome of design projects and the perceived readiness of clients to work with design. The consultants adapted their practices for successful project outcomes, as well as to succeed in securing project commissions. We discerned three distinct types of practices the consultants adapted for more effective briefing and sales—customised communication, codified conducts and productised services. We describe how consultants used these practices to bridge uncertainties and minimise challenges before projects were commissioned.

Beyond Documentation: Broader Context of Briefing in Design Consulting

It is rarely possible to comprehend all aspects of a problem at the outset when designing (Lawson, 2004, p. 29). The co-evolution of problems and solutions (Dorst & Cross, 2001; Maher & Poon, 1996) often requires designers to re-scope and change the course of projects as they proceed and the unexpected unfolds. Therefore, expert designers act as “ill-behaved” problem-solvers, who purposefully consider the initial brief as ill-defined (Cross, 2006, pp. 99-101) and seek new information and knowledge to appropriately reframe the problem(s) at hand as a project evolves (Paton & Dorst, 2011; Schön, 1995). Practical guidelines on briefing also recommend designers continuously revise briefs throughout projects in partnership with clients (e.g., Blyth & Worthington, 2001; Phillips, 2004). Prior studies point to the significance of revisions in design work (Berends, Reymen, Stultiëns, & Peutz, 2011; Jin & Chusilp, 2006; Smith & Tjandra, 1998) and recommend using design briefs flexibly throughout projects (e.g., Jevnaker, 2005; Ryd, 2004).

However, the milieu of design consulting does not readily cater for such iterative briefing practices. A number of studies point to challenges in the interactions between client companies and external designers (e.g., Bruce & Morris, 1994; Hakatie & Ryynänen, 2007; Kurvinen, 2005; Tomes, Oates, & Armstrong, 1998; Tzortzopoulos, Cooper, Chan, & Kagioglou, 2006). Other studies suggest that client companies display varying degrees of proficiency in using design, which has an impact on how they work with external designers in projects (e.g., Micheli, 2014; Ramlau, 2004; von Stamm, 1998). To this end, in discussing the management of internal and external designers, Bruce and Morris (1994) describe design briefs as “nailed down” documents for external designers rather than iterative tools for reframing, as external design consultants often work within inflexible agreements that are difficult to alter over the course of projects. Further studies have explored different briefing practices designers can use to elicit and negotiate about project requirements, including a method for designing more accessible buildings by involving users in the briefing process (Luck et al., 2001), an ethnographic approach for inclusive briefing (Dankl, 2013) and a conceptual framework to elicit and manage clients’ requirements (Haug, 2015). However, what is yet to be addressed is the real-life conditions for briefing in design consulting and the challenges occurring during the interactions with potential clients.

Given the impact on the work of designers, the professional context of briefing in design consulting is an important domain of research in its own right. In responding to this gap in the literature, we investigate the ways in which industrial design consultants cope with and potentially mitigate such challenges in settling the briefs for projects with clients. We inquired into how industrial design consultants initiate project discussions with potential clients, if and how they prepare for briefing, when and how the conversation about new projects emerges, and if and how the formulation of a brief influences the later phases of projects.

Method

We pursued an inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to shed light on how design consultants go about formulating briefs for new projects with clients and the professional context within which the consultants operate. We used a combination of purposeful (e.g., Patton, 2002, p. 230) and snowball sampling (e.g., Faugier & Sargeant, 1997) in locating experienced consultants to interview for our study. We began our search for consultants by reviewing the portfolios of the consultancies listed on the website of the Finnish Design Business Association (December 2013), approaching founders, directors, and senior designers of those consultancies with a strong emphasis on and significant history in industrial design. Next, we extended our search by consulting professors and lecturers at Aalto University, who provided us with additional referrals to experienced consultants from their networks. At the end of each interview, we asked the interviewees for referrals to other consultants with similar levels of experience. We ended our search for consultants when saturation started to emerge in the referrals.

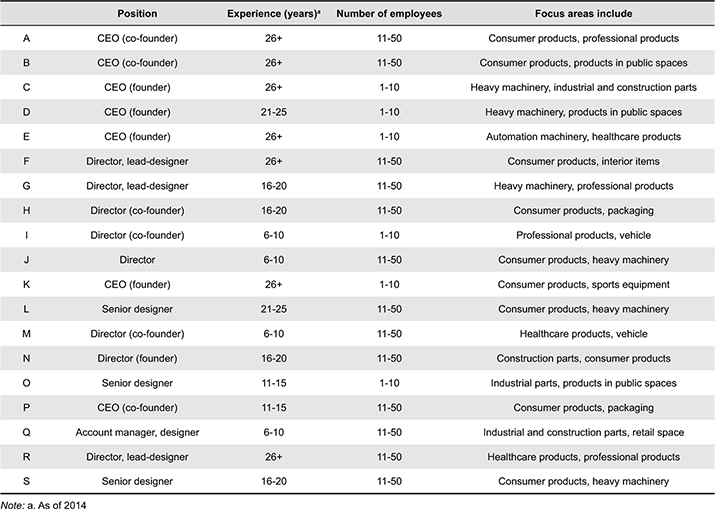

Our data corpus includes 28 interviews along with briefing and sales related documents from 19 industrial design consultants in Finland. The work experience of the consultants ranged from 8 years to 39 years with a mean of 18 years (as of 2014). They worked for 17 Finnish industrial design consultancies, none of which operated under a strong emphasis on the name or reputation of a single designer. By the time of the interviews, the majority of the consultants held senior positions in the consultancies and worked directly on acquiring projects and settling briefs with clients. All the consultants have higher education in industrial design, except for one who has a degree in architecture. At the time of the interviews, the consultancies were based out of five major cities in Finland.

The focus areas of the consultants ranged from consumer goods and packaging to healthcare and heavy industry products. The types of projects discussed during the interviews include boats, cleaning tools and machines, control rooms, drain elements, kitchen tools, laboratory and medical equipment, office furniture, and ventilation system components. Some of the consultancies also did graphic design, spatial design and interaction design for their clients. During the interviews, no project case was discussed in which the design consultancy had proposed a preconceived (original) design to a client for manufacturing (for more extensive discussion on such engagements, see e.g., Rees, 1997, pp. 128-130).

Table 1. List of interviewees.

Data Collection and Analysis

We approached briefing as a phenomenon in its social context (e.g., Eriksson & Kovalainen, 2008; Ritchie, Lewis, Nicholls, & Ormston, 2014), and performed two rounds of semi-structured interviews. In the first round, we inquired into the professional context and the briefing practices of the consultants in order to discern interconnected patterns (themes) within their accounts (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We also collected briefing and sales related documents for data triangulation (e.g., Thurmond, 2001). Similar to the method employed by Person, Snelders, and Schoormans (2016) we invited the interviewees to participate in the analysis process and comment on our initial understanding of the data during the second round of the interviews (for more in-depth discussion on “co-constitituted” or “mediated” accounts in qualitative research, see e.g., Finlay, 2002, p. 218; Ormston, Spencer, Barnard, & Snape, 2014, pp. 6-8). Below, we describe our process in detail with appendices for transparency (e.g., Lewis, Ritchie, Ormston, & Morrell, 2014, pp. 347-366; Pratt, 2008, p. 501, 2009, pp. 858-860).

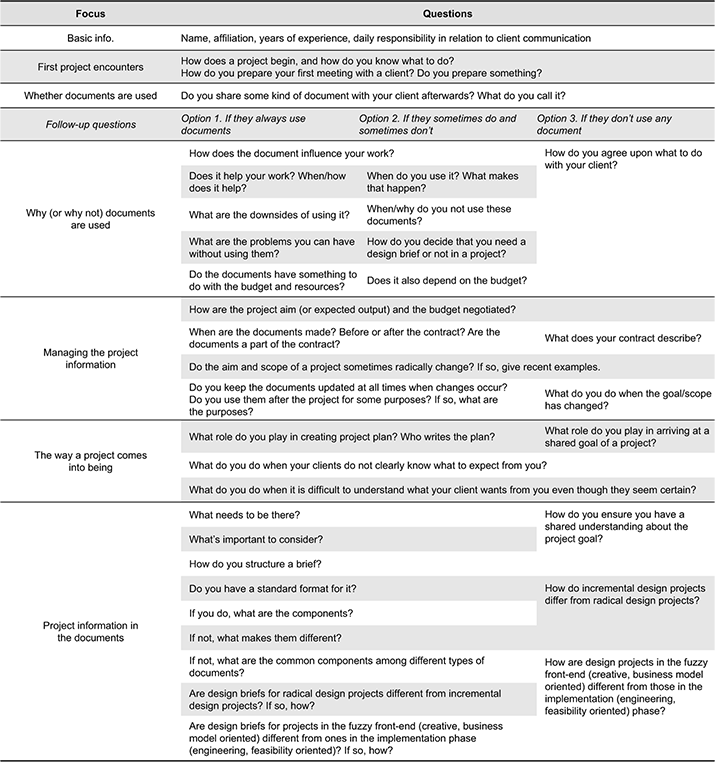

The first round of interviews were undertaken between January and October, 2014. The first author interviewed all the consultants using a topic guide to structure the inquiry, while keeping the conversation open-ended and paying close attention to emergent topics during the discussions. The topic guide was prepared by both authors, and covered questions about how the interviewees approached potential clients, how a discussion on a potential project typically began, when and how briefing took place, whether and how the consultants prepared for briefing as well as whether there were differences in the briefing practices depending on the types of projects (see Appendix 1). In order to prevent leading questions, we intentionally avoided using expressions such as ‘briefing’ and ‘design brief’ unless they were first brought up by the interviewees (e.g., Ritchie et al., 2014). All the interviews took place in the offices of the consultancies, except one that took place at a café for the convenience of the interviewee. The interviews were conducted in English and audio-recorded with consent of the interviewees. The consultants were assured that they would be speaking about their work under confidentiality and anonymity. The length of the interviews ranged from 30 to 106 minutes with a mean of 72 minutes, generating 20 hours and 38 minutes of interview material for analysis. At the end of each interview, the interviewees were asked to share exemplary documentation. Seven interviewees agreed to do so and shared documentation from projects, including brochures, offer documents, design brief documents, briefing checklists and partial material from a workshop manual. Details about individual projects and clients were redacted from the documents prior to being shared with us. Those documents written in Finnish were translated into English by a professional translation firm.

We followed the systematic process articulated by Braun and Clarke (2006) to give order to, and discern patterns in, the reports of the interviewees. First, the first author fully transcribed all the interviews and coded the transcripts following in vivo coding (e.g., Spencer, Ritchie, & O’Connor, 2003, p. 203), which enabled familiarisation with the data. Next, a systematic and comprehensive coding scheme was developed iteratively in dialogue between the first and the second authors, relying upon a combination of focused coding and axial coding (Saldaña, 2013). The focus codes covered background information (about the design consultants and the consultancies they worked for), briefing procedures (what takes place and in which order), change during projects (why it happens and how it was dealt with), design objects (what kind of designed objects were mentioned), documents (offer, design brief, agreement), meetings (purpose and preparation) and sales activities (how to find clients). The axial codes included client type (small–large), design culture (high–low) and project types (radical–cosmetic).

In iterative reviews of the transcripts, emergent codes were added to capture the briefing practices of the consultants, while existing codes were updated and merged for better fit and/or coverage. The systematisation of our data and iterative thematic analysis arrived at a code system of 10 main codes and 35 sub-codes (see Appendix 2). Patterns emerged from the results of the coding in regard to how briefing and sales played out in the reported practices of the consultants, and how such practices were seen to be influenced by the professional consultancy context within which they operated. In particular, our analysis brought to light a set of distinct briefing and sales practices the consultants adapted to alleviate the everyday challenges they faced when detailing the scope and phases of projects with potential clients. These challenges were in many ways described in relation to uncertainties they had to manage before and throughout projects, and the degree to which potential clients were perceived to be ready to bear with these uncertainties and to work with external design experts more generally.

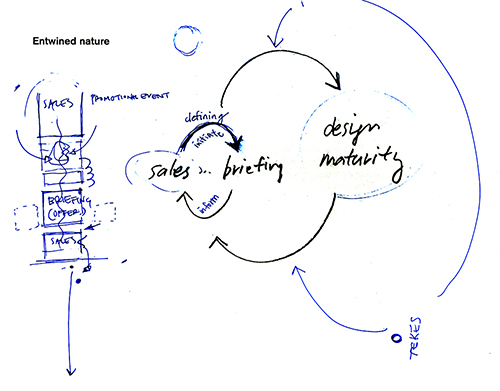

The second round of interviews were undertaken between March and April, 2016 and the interviewees were invited to participate in the analysis and evaluation of our initial understanding of the data (e.g., Finlay, 2002, p. 218). Following maximum variation sampling (Marshall, 1996), the first author returned to nine of the consultants that differed in their practices, specialisation, size of the consultancy organisation and type of clients. The interviews were organised around a set of visual aids (diagrams) to support the consultants in reviewing our findings (Crilly, Blackwell, & Clarkson, 2006). The diagrams were designed to give an overview of the initial findings in terms of (1) the interconnectedness between briefing and sales, (2) the varying readiness of clients to work with design, (3) the distinct consultancy practices for briefing and sales, and (4) the importance of, and the practices for, long-term relationship building with clients. Involving consultants in the analysis process enabled us to solicit open-ended feedback on our findings and gain further insights that could deepen and/or modify our understanding. This was achieved by presenting intentionally incomplete diagrams as “works-in-progress that depict possible representations” (Crilly et al., 2006, p. 21). The consultants were asked to comment on and add to the diagrams by writing on and drawing on them, and many readily reflected upon their daily work against the information in the diagrams (see Appendix 3 for an example).

The interviews were conducted in English. All the interviews took place in the offices of the consultants, except one that took place at a café for the convenience of the interviewee. The length of the interviews ranged from 49 to 121 minutes, with a mean of 72 minutes, totalling 11 hours and 56 minutes. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by a third-party agency. The first author reviewed the transcripts and annotations from each interview to identify discrepancies and complementarities. Most of the consultants confirmed the briefing practices we had uncovered, and others provided additional information and examples that enhanced our analysis.

Briefing Terminology in Finnish Industrial Design Consulting

Extant literature consistently uses the English terms ‘design brief’ and ‘briefing’ to describe the document containing the essential information for projects and the process of identifying, communicating and documenting this information (e.g., Blyth & Worthington, 2001; Cooper & Press, 1995; Luck et al., 2001; Paton & Dorst, 2011; Phillips, 2004; Ryd, 2004). During our interviews, however, these terms were referenced in a multitude of ways.

The consultants described how they used various types of documents during the initial encounters with clients. ‘Agreement’ (‘sopimus’ in Finnish) and ‘offer’ (‘tarjous’ in Finnish) were used by all the consultants. Considered as industry-standard, the content of an agreement revolved around settling routine issues, such as the responsibilities of the involved parties, intellectual property rights, and payment terms1. An offer was described as being more project and context specific, covering the scope, the anticipated steps, the allocated time for each step and, hence, the corresponding project fees. Some of the consultants also described how they used ancillary documents to clarify project details during the briefing process. The contents of the ancillary documents we received from the consultants included a wide range of information, such as qualitative information about user needs, value propositions and the brand images pursued in projects, as well as technical specifications, such as dimensions, operating temperature and descriptions of technological platforms. The consultants using ancillary documents stated that the content of these documents could also be included in the offer when the scope of a project was small, or if the aim of a project was incremental and straightforward.

The ancillary documents were referred to as the ‘specification’ (‘toimeksianto’ or ‘speksi’ in Finnish) or ‘design brief’. As no encompassing terminology emerged across all the interviewees and the contents of different documents varied and overlapped, we approach the ancillary documentation as consultant and project specific. Further, for the sake of simplicity, we approach all these documents—together with the information found in the offers—as design briefs in presenting the reports of the consultants below. The ways in which the scope of projects was formulated and negotiated with clients were referred to as ‘project planning’, ‘briefing’, or simply ‘offering’. We refer to all these terms as briefing to cover the similarities and interconnectedness in the described activities.

Professional Context of Briefing in Industrial Design Consulting in Finland

The everyday challenges of the consultants during briefing and their attempts to resolve such challenges in securing commissions from clients were a reoccurring topic during the interviews. The challenges often revolved around negotiating the scope of projects prior to project commission while also selling design expertise to potential clients, and the ways in which briefing and the resulting documents could support and/or limit the work of the consultants in later stages of projects.

Consultants predominantly described the process of searching for potential clients—both ‘old’ and ‘new’—and initiating project discussions as being unpredictable. The consultants saw little difference between a client with one or two past project engagements (deemed ‘old’) and a client without any prior project engagement (deemed ‘new’). Although requests for proposals could come from both old and new clients, there is no guarantee of future project commissions after a project is finalised and delivered. Consequently, most of the interviewed consultants stated that they were regularly involved in making cold calls in the pursuit of enlarging their client base. Furthermore, the consultants stated that it can take months or years before a face-to-face discussion for a project could take place with a new client.

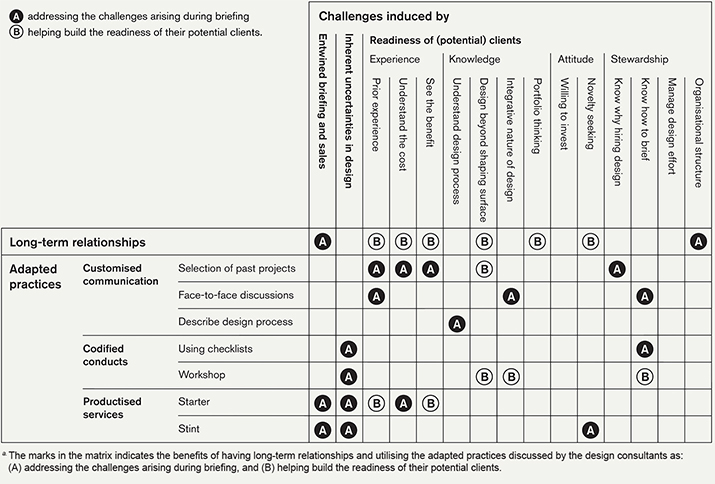

The consultants described how developing long-term relationships with clients could be effective in avoiding some of the challenges during briefing and sales in the pre-project phase (for an overview of the described benefits of long-term relationships, see Appendix 4). In particular, the mutual trust and respect built over a long period of cooperation was seen to simplify briefing, and more broadly how they sold their expertise to clients in projects. Similar to the findings of Bruce and Docherty (1993, pp. 408-409), we found that staying in regular contact with clients in long-term relationships enabled the consultants to conceive new project ideas together with clients as more equal partners. In such relationships, the fees for projects were often invoiced in a more open-ended manner, e.g., at the end of each month or quarter. Thus, all the consultants greatly valued long-term relationships with their clients and took proactive measures to establish and sustain them. For example, the consultants described how they took on projects for simple three-dimensional modelling for years (Consultant_C), lowered their hourly rate for projects that had lasted longer than expected (Consultant_I), as well as declined projects when purchasing ready-made parts seemed to be a better choice for a client (Consultant_S). However, only few project commissions turn into long-term relationships, and, thus, the search for new clients to enlarge their client base remained a daily routine within all of the consultancies.

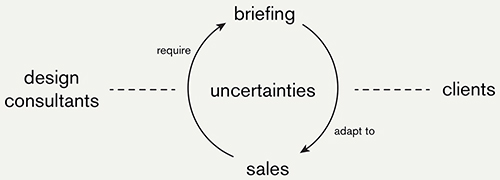

This professional context of briefing with clients—within which new client relationships may begin to form—represents the focus of the present study. As visualised in Figure 1, the consultants described briefing and sales as being entwined: briefing adapted to sales situations while sales required briefing to make informed cost estimates when preparing an offer.

Figure 1. Professional context of briefing in design consulting.

Briefing began with identifying the specific needs of a (potential) client from the very first contact, and continued by exploring possible directions, delineating the scope, and detailing the phases of a project throughout the interactions prior to a project commission. It became clear that time-based pricing was the dominant model used within industrial design consulting in Finland2: that is, the fee for a project was estimated based on the time to be spent3. The allocated hours, and hence the fees for each phase of a project, were transparently stated in the offer documents we collected, and the consultants described how clients often rejected or asked for modifications in specific phases in setting the scope of a project. Once an offer was accepted, the resulting project plan was seen as being rather fixed and rigid, as exemplified in the following quote:

[B]ecause that’s where everything gets defined, that’s where the real conversations take place, we actually discuss needs and modes of working … once we get to the kick off, we’ve already locked all those models down, and then it’s work, and that’s just implementation. (Consultant_J)

Several of the consultants described how this entwinement, in tandem with the time-based pricing, resulted in a discontinuity of briefing and directly influenced their work once a project had been commissioned. The formulation of a brief was seen as being critical by the consultants in the short term, as it affected the number of billable hours, as well as whether or not a client would commission a project. The consultants also stressed the longer-term implications of briefing, as the plan and predetermined time could directly influence their possibilities to succeed in projects. To this end, the consultants stressed the importance of rigorous briefing prior to project commission, as it formed a prerequisite for producing successful outcomes, and thus could affect the likelihood of selling more projects in the future and building long-term relationships with clients.

With no guarantee of securing commissions, however, the consultants stated that they were disincentivised to allocate excessive resources for briefing during the pre-project phase. The professional context of briefing within which the consultants operated did not always leave enough time and resources for the briefing task itself, and a number of the consultants considered putting too much effort into briefing as being costly, or even risky:

… first project with the customer is usually really bad business, and it’s the second or third or the fourth project which is actually helping us … because the briefing process is so hard and it takes so much time and there’s so much risk in our end. (Consultant_M)

Following this line of reasoning, briefing was referred to as being ‘the most important [phase of a project] to the customer [that] isn’t invoiced’ (Consultant_M), or ‘free work [that] never stops’ (Consultant_E). In addition, inherent uncertainties both during the process and in the outcome of projects posed marked challenges for the consultants in delineating the scope and detailing the phases of projects in advance. The situation was further complicated by the challenges arising from clients’ (sometimes limited) readiness to work with design, such as having undefined aims and unrealistic ambitions. In the sections that follow, we elaborate on this broader context of briefing in industrial design consulting and how the consultants saw it being implicated in their work.

Inherent Uncertainties in Design and Rigidity in Clients’ Budgeting

… even though we are in a project where honestly nobody knows what the outcome will be, the purchase process requires something to be documented. That is ridiculous because of course we can put something down, but we all know this is not necessarily what we are going to really have at the end. (Consultant_H)

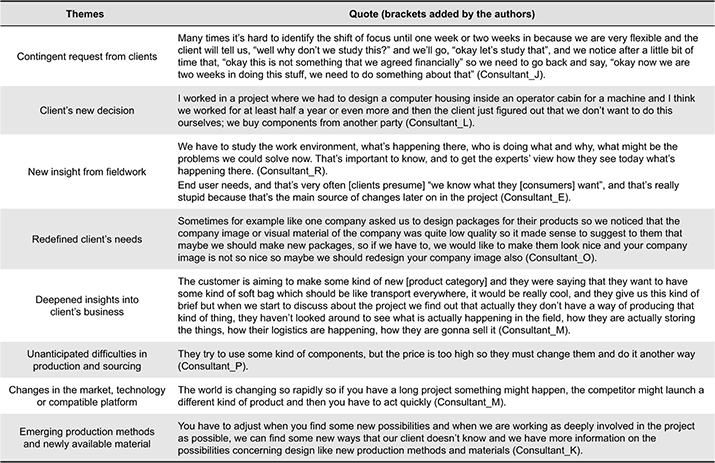

Inherent uncertainties about the process and outcome of a project posed an immediate concern to the consultants in settling the brief for new projects with clients, as exemplified in the quote above. The uncertainties can be broadly categorised as arising from (1) the nature of design projects where the consultants are asked to work on things that do not exist yet, or (2) changes during the course of a project that are often outside the control of designers. The consultants described the nature of design consulting as ‘selling something you don’t see, you don’t know, you don’t feel’ (Consultant_C). This inherent uncertainty in design consulting was frequently discussed to be extending to unforseen changes that occur during the project, including new decisions or contingent requests made by clients, insights gained from fieldwork, and novel production methods made available (see Appendix 5 for exemplary quotes). The scope and phases of a project were, therefore, often subject to revisions, which raised challenges in delineating the entire project plan in detail upfront with a potential client. Further, the negotiations on the scope and phases between the consultants and their clients during briefing were invariably influenced by clients’ willingness to venture into the unknown, as well as their experience and knowledge in using design.

The incompatibility between the inherent uncertainty of such projects and the rigidity in clients’ budgeting posed a daunting challenge to the consultants in settling a brief. Although the consultants were aware of the uncertainties, they needed to detail the scope and phases in project offers (briefs) to clients. Furthermore, while some clients were open to shifting the focus at later stages in the pursuit of better outcomes, most clients were less enthusiastic about adapting such changes in terms of the total budget. Consequently, the consultants stated that changes in most cases needed to be managed within the agreed budget for a project by, for example, reducing the quantity of visual production.

Exploratory and radical design projects were described as involving more uncertainties than incremental ones, and typically, therefore, were perceived as more challenging for briefing. Examples of such projects from the interviews included launching a novel product, building a product or service scenario around a new technology and establishing a design policy for an international corporation with diverse product and service offerings. The consultants described such projects as being larger and lengthier than incremental ones, invariably requiring sizable exploration phases whose outcomes were often also more open-ended and/or “ill-defined” (e.g., Cross, 2006, pp. 99-101) than those of more incremental projects. Even for such projects, nevertheless, the consultants stated that the entwinement of briefing and sales and rigidity of clients’ budgeting often necessitated predetermining the scope and outcome of such projects upfront, as noted above.

Readiness of Clients to Work with Design

Expressed in terms of a company’s ‘culture’ to manage and orchestrate design efforts, the (perceived) readiness of clients to hire and work with design consultants formed a reoccurring topic in discussing the briefing practices of the consultants, as noted above. Resonating with extant literature (e.g., Micheli, 2014; Ramlau, 2004; von Stamm, 1998), the readiness was seen to both enable and hinder the consultants to productively engage with clients in briefing for new projects.

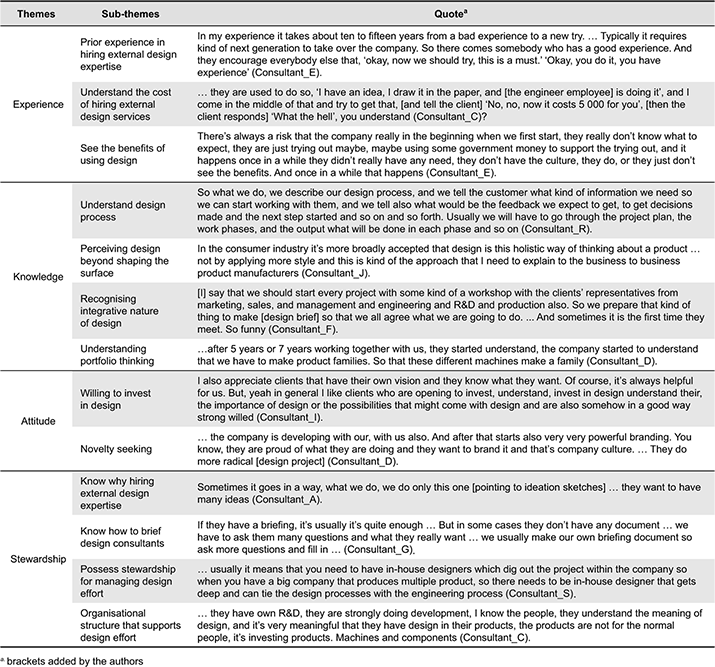

In inductively analysing the reports of the consultants, we extract four recurring themes, including 14 sub-themes, from the ways in which the consultants described the readiness of their clients: (1) experience, (2) knowledge, (3) attitude and (4) stewardship (see Appendix 6 for exemplary quotes). The themes can be seen to be interconnected, as the reports of the consultants frequently spanned multiple themes. Moreover, while not all the consultants directly articulated the readiness of clients in terms of distinct levels, it is possible to discern patterns in how they described the evolution of the readiness of clients over time:

[When] they don’t have much experience about design [Experience: Prior experience in hiring external design experts], they don’t really know what to expect [Stewardship: Know why to hire external design experts], and in a situation like that you never invest a lot [Attitude: willing to invest] in something you know nothing about [Knowledge], so they invest a little, and they see what happens. (Consultant_E, brackets added by the authors)

A positive first-hand experience of using design was frequently described as a precondition for clients to develop sustained interest in hiring designers, and hence formed a cornerstone in articulating the perceived readiness of clients to work with design during the interviews. Conversely, a negative experience in using design was described to have caused clients stop working and/or were to be unwilling to engage with design for prolonged periods of time, as exemplified below:

If it’s the first time that [a] company uses design, it’s very sensitive ... But after that, when you have maybe been successful in this first project, it’s so much easier to continue to cooperate. But, if the first project goes badly, it’s very difficult to start [a new design project]. (Consultant_D, brackets added by the authors)

Consultants described how positive prior experiences aided clients in understanding the benefits and, thus, accepting the cost of engaging with external design experts. As noted during the interviews, it was not uncommon that clients with little experience underestimated the time and resources required to fulfil their expectations regarding the outcomes. Small companies and entrepreneurs were often described as having limited experience in using design and were, therefore, considered to be particularly challenging clients during the pre-project phase: ‘They don’t have any kind of clue how much it would actually cost and how much time they would need’ (Consultant_G).

Grounded in clients’ prior experiences in using design, knowledge about design was described as being important in bringing relevant information to light when briefing for new projects. Knowledge was articulated in terms of being aware of the multifaceted and integrative nature of design, perhaps suggesting that the client had a more advanced understanding about design and the work of design consultants. Lacking such understanding was seen as problematic, since clients were not always able to provide the relevant information needed in settling the brief for a project and/or to effectively engage with design consultants in projects. For example, in order to produce successful outcomes, it was considered to be beneficial if clients understood that designers need to investigate various aspects of a client’s business to help the client explore possible directions and delineate the exact scope for a project.

The attitude clients displayed towards engaging with external design experts, in addition to experience and knowledge, was also described as having a decisive impact on briefing. Specifically, as noted during the interviews, whether a potential client saw design as an investment with strategic value or just as an additional cost was sometimes seen to have far-reaching implications in setting the direction and scope of a project during briefing. The attitude towards design was found to shift slowly, often gradually over several years. This gradual shift of attitude—coupled with the aggregation of a series of positive experiences—was noted during a number of the interviews.

Finally, working with clients that displayed stewardship was considered the preferred situation by a number of the consultants, since such clients were better equipped to effectively lead and orchestrate design efforts both within their own organisations and working with external designers. As a professional (or a team of professionals) dedicated to supervising design work, the ‘professional design buyer’ (Consultant_P) was seen as having the capabilities to articulate the specific design needs for a project, and holding the position needed to establish the necessary connections within the client organisations during briefing in the pre-project phase and afterwards:

… usually it means that you have in-house designers which dig out the project within the company so when you have a big company that produces multiple product[s] so there needs to be [an] in-house designer that gets deep and can tie the design processes with the engineering process. (Consultant_S, brackets added by the authors)

The consultants saw stewardship as essential for clients in order to procure appropriate design expertise and to effectively integrate design consultants within the larger development processes of companies. For instance, clients with stewardship were seen to be able to make more focused project procurements including commissioning idea sketches to explore different options (Consultant_A) or scenarios to envision the future for new product or service offerings (Consultant_G).

The consultants noted that a higher degree of stewardship was experienced mainly when working with large and multinational companies with a longer track record of working with external design experts. However, the consultants also noted that companies of significant sizes could also lack stewardship. They noted that lack of communication and power struggles between different functions (departments) in larger organisations could present challenges for briefing. Further, while stewardship was for the most part described as being positive for briefing, some consultants noted that an overly strong vision from a client’s internal designer(s) could limit their work and their possibilities to aid clients during projects.

Adapted Practices for Briefing and Sales

In discussing the professional context of design consulting in which consultants interacted with their (potential) clients, the consultants described how they adapted their practices for briefing and sales to the situation at hand. We derive three different types of such practices from the reports of the consultants: (1) customised communication, (2) codified conducts and (3) productised services. These adapted practices were described as bridging uncertainties in design projects for, and to enhance the interactions with, potential clients in the pre-project phase. Additionally, these were seen to help develop the readiness of clients to work with design in the long term (for an overview of the described benefits of utilising the adapted practices, see Appendix 4). The practices differ in terms of the degree of systemisation and responsiveness (proactiveness) suggested in the actions of the consultants when interacting with clients, as well as the degree to which textual and visual aids were used to support such interactions. The practices were identified at both individual and consultancy level, as two designers at the same design consultancy articulated preferences for different types of practices during the interviews.

Customised Communication

Tailoring the discussion for (potential) clients, or customised communication as we refer to it hereinafter, was described as a necessity in interacting with clients and settling the brief for projects. The consultants described several ways in which they used customised communication, all of which seemed to be preparatory and/or reactive by nature.

Most of the consultants described that they did quick (Internet) searches on the business of potential clients, including their current product/service offerings, market position, and past engagements with design in order to prepare and ‘tweak’ (Consultant_I) what to present in the first meeting with a potential client. In doing so, the consultants described that they aimed to not only display projects of relevance for potential clients’ businesses but also ‘different kinds of design projects’ (Consultant_O) to spark the imagination. Moreover, by avoiding ‘professional jargon’ (Consultant_K) and presenting idea sketches from past projects (Consultant_A), they also hoped to establish a common understanding from which to explore possible project directions with clients during meetings.

The consultants stated that they frequently received incomplete information from clients, especially from those with limited experience in or knowledge about using design. Consequently, many of the consultants found face-to-face discussions crucial in order to have an opportunity to ask the ‘right questions’ (Consultant_K, Q) and to ‘translate’ (Consultant_E) what and how a potential client responded. During such discussions, a number of the consultants described how they used hand drawings to specify problems and rapidly iterate preliminary project plans. Some of the design consultants also stated that they often describe the design process step-by-step during the initial meetings in order to request specific feedback and input in certain phases of a project. Spending time on describing the design process was seen to be particularly useful to bridge uncertainties for clients with little or no prior experience in using design or product development in general.

The inherent uncertainties in design projects and the varying readiness of clients to work with design made customised communication a natural part of briefing and sales. Further, a number of the consultants remarked on the comparatively small market for industrial design consulting in Finland, and, therefore, considered pursuing a high degree of specialisation and targeting only specific types of clients as risky. This made the reactive and perhaps opportunistic approach of customised communication more sensible in responding to the varied needs of clients. That said, a number of the consultants described how they faced reoccurring challenges in interactions with different clients and had adapted their practices accordingly. For example, a number of the consultants described how they actively sought to meet with clients face-to-face in order to better interpret clients’ needs and to rapidly iterate preliminary project plans, as noted earlier.

Codified Conducts

Some of the consultants described how they had systematised their briefing practices and the accompanying use of visual and textual aids that they used in interacting with clients. They also described that they considered such codified conducts as essential for achieving successful outcomes in projects. In particular, codified conducts were described as helpful in conducting a thorough briefing, which reduced costly errors in later stages of design projects. As an example, one consultant described how the consultancy he/she worked for supplied him/her with an extensive checklist to use in settling the brief with clients. Another design consultant described how he/she organised so-called ‘briefing workshops’ with a self-developed multiple-page template.

Using checklists was seen to be particularly relevant for projects involving a high degree of uncertainty, as the information obtained from the checklists made it possible to reduce assumptions and stimulate topical decisions at an early stage. The checklists we received from the consultants covered a wide range of topics such as project background, intended use, technical details/parts, manufacturing specifications, marketing and sales, and project management. However, some of the consultants expressed concerns that some checklists were too extensive, and that it could be difficult to go through all items on a checklist at the initial (often short) meetings they had with clients.

Discussions on briefing workshops displayed a higher degree of codification in the interactions between the consultants and their clients. The reviewed manual also included richer and more structured guidance than the checklists. Among other things, the manual included diagrams and group activities with detailed assignments to be followed in working (interacting) with clients. The overall aim of hosting briefing workshops was articulated in terms of establishing a ‘collective brief’ (Consultant_A) for a project, in which the various topics from across relevant functions of a client organisation were identified and synthesised into a single document.

While there were similarities in the ways in which the consultants described the benefits of briefing workshops, the exact timing and overarching rationale for running a workshop differed between the consultants. For instance, one consultant mainly worked for larger clients in a specialised business area. Many of the clients in this business area had abundant resources and a great deal of experience in using design. The consultant accordingly described how he/she ran workshops at the initial meetings as an investment in staying up-to-date with changes within client organisations and in deepening his/her own expertise in the specialised area in which his/her clients operate. In contrast, another consultant, who for the most part worked with start-ups and small and medium-sized companies, only pursued briefing workshops after a project had been commissioned. The main reason for this was that the smaller companies that he/she worked with normally had limited resources (only enough for a period of a few days or weeks) and held little or no experience in using design. The business areas of his/her clients were also rather heterogeneous, which limited the possibilities for standardisation. To this end, once a project had been commissioned, the overarching aims of hosting a briefing workshop were to prioritise and settle on a meaningful outcome for the project with the limited resources available. In addition, the workshops enabled the consultant and his/her clients to learn from each other – the clients learning about design and briefing and the consultant learning the specifics about the clients’ businesses.

Productised Services

We noted that some of the consultants segmented their work for clients, and in doing so circumvented some of the uncertainties inherent in the briefing and sales process. In particular, a small number of the consultants described how they systematised and packaged their expertise to become more ‘product-like’ (Valminen & Toivonen, 2012, p. 274) and, by doing so, sought to more proactively reconcile the challenges they faced during briefing and sales. We identify two such types of project packages, or productised services, that together capture these product-like consulting services that were discussed by some of the consultants.

The first type of project package, Starter (as we refer to it hereinafter) consisted of introductory design projects with pre-set outcomes that one of the consultancies offered to their clients. Building on a government-supported programme for design promotion, which most of the interviewed consultants had participated in, Starter was intended for clients with little or no experience in using design4. It was organised around the delivery of specific outcomes such as a few design ideas and/or surface renderings within a short project period. The overarching aim of running such short and predefined projects was to lower the initial threshold (cost) of making a commission as well as alleviate some of the uncertainties clients associated with specifying the outcomes for a commission. Commissioning a Starter was also described as an opportunity for clients to improve their readiness to work with external design experts by gaining concrete experience in using design. For the consultants, selling Starter was seen as a way to get a project commission from a potential client who might otherwise have chosen to stop trying design due to the inherent uncertainties they associated with procuring design. In a similar vein, the design consultants also stated that they had sometimes spent more resources than what was promised in the Starter package in order to impress clients and to increase the likelihood of selling more projects in the future. However, one of the design consultants criticised the format of Starter for occasionally ‘not creating sound solutions’ and providing a superficial outcome given the limited time.

The second type of predefined project package, Stint, was intended to address the challenges arising from the high level of uncertainty that typically emerged in commissioning and engaging with radical design projects. Stint was actively marketed by one of the consultants5. Inspired by methods from ‘agile software development’ (Martin, 2003), a Stint required the design consultant and client personnel to work together as a team for a short period at an intensive pace during which they gained insights into novel product/service ideas through field observation, prototyping and rapid iterations. Stint was described as being helpful in focusing on the exploration phase itself without having to settle the scope of a full development project involving excessive levels of uncertainty. After the necessary insights had been accumulated after one or more Stints, a full-fledged development project could commence if needed. In this sense, from the perspective of briefing and sales, Stint is perhaps best described as intensive teamwork productised for learning about the problem and solution spaces in co-evolution and/or as a way of engaging client personnel, while leaving detailed design work to the next (potential) project.

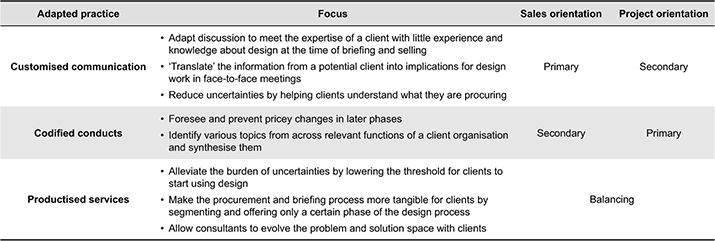

Orientation of Each Adapted Practice

In discerning how pursuing each adapted practice was described to help alleviate specific challenges in the early stage of briefing and sales we noted that the adapted practices were often discussed as being slightly more sales or project oriented. By sales orientation, we mean that the described practices seemed to be more inclined to alleviate specific challenges that emerged in selling design expertise to clients. By project orientation, we mean that the described practices seemed more intended to increase the opportunities of consultants to reach successful outcomes in projects. Table 2 presents a summary of the focus and orientation of each practice.

Table 2. Focuses and orientations of adapted practices.

Customised communication was predominantly discussed in terms of alleviating the challenges the consultants encountered due to clients’ lack of experience, knowledge, and/or organisational structures (stewardship) for using design. Therefore, the benefits of using customised communication can be summarised as alleviating the uncertainties clients face in procuring design by communicating at their level of capability and helping them understand what they are about to procure. In this sense, it is probable that the primary reason why design consultants engage in customised communication is to secure sales.

In contrast, codified conducts were frequently discussed in relation to reducing costly errors at later stages of projects by engaging in more systematic practices for briefing to surface relevant information earlier in projects. For example, in pursuing codified conducts, consultants sought to identify various topics from across relevant functions of client organisations and synthesise them into a single briefing document through rich and structured guidance. To this end, the overarching reasoning for pursuing codified conducts is perhaps best described in terms of helping (potential) clients to understand design in a more holistic manner and build their readiness for using design more generally. As this entailed work prior to project commissions, pursuing codified conducts was intended towards achieving better outcomes. The immediate need for sales is thus a somewhat secondary concern.

Productised services were chiefly described as attempts to address the challenges posed by both the entwinement between briefing and sales and the inherent uncertainties facing clients and consultants in embarking on new projects. Starter was seen to alleviate the clients’ burden of uncertainties by lowering the threshold to procure design while raising the readiness of clients through exposure to design. Stint was seen to cater to experienced clients with a proactive attitude, enabling the design consultants to evolve problem and solution spaces with clients while simultaneously being paid for the time spent. Accordingly, the reason for engaging in productised services can be seen as seeking a balance between securing more sales and pursuing better outcomes.

Conclusion and Discussion

Our study brings to light important questions about the character of design and briefing in the professional context of industrial design consulting. The first set of questions pertains to the nature of design problems and the role of briefing in aiding designers to hone in on the problem at hand. In both academic (e.g., Lawson, 2004; Ryd, 2004) and professional (e.g., Blyth & Worthington, 2001; Phillips, 2004) literature, effective briefing is conceptualised as being adaptable to change and responding to the needs and opportunities arising during projects. In analysing the reports of the consultants, we noted a discontinuity in the briefing process once the sales process for a project ends and a project is commissioned, which challenges the practical possibilities for designers to adapt and iterate the brief. Although the consultants were aware of the evolving nature of problem and solution spaces in design (Dorst & Cross, 2001), they needed to detail the scope and phases in project offers (briefs) to clients. Once accepted by a client, changes to an offer were predominantly seen as problematic as they could have implications for the budgetary planning of a project. At the same time, the competition the consultants faced in winning commissions incentivised them to avoid allocating resources for briefing during the pre-project phase and to limit the fee (hence the time to spend in a given project) in project offers, which also constrained their work in later stages. How to balance briefing for sales with the evolving nature of design problems accordingly represents a basic concern in design consulting.

The second set of questions concerns the milieu of design consulting and the role of clients in settling the brief for projects. A number of studies address the importance of consultants for companies in acquiring capabilities in design (e.g., Abecassis-Moedas & Pereira, 2012; Bruce & Morris, 1994; Calabretta, Gemser, Wijnberg, & Hekkert, 2012; Perks, Cooper, & Jones, 2005). A reoccurring theme in this literature is that, while design can benefit companies in many ways, client companies often lack the knowledge and skills needed to procure expertise in design effectively (e.g., Bruce & Jevnaker, 1998; Ramlau, 2004). Our findings add to such reports by pointing out that commissioning a project involves “silent” design work (Gorb & Dumas, 1987) of clients, which unknowingly and/or unintentionally impact the work of designers in projects. In particular, we found that the entwinement between briefing and sales as well as the nature of design problem in design consulting unveiled covert participation of the clients in settling the brief for projects, which could decisively impact the work of the consultants. Past studies suggest that long-term client-design consultant relationships can help to overcome such challenges (e.g., Bruce & Docherty, 1993; Bruce & Jevnaker, 1998; Buchner, West, & Zaccai, 2000; Gwinner, Gremler, & Bitner, 1998; Jevnaker & Bruce, 1998; O’Connor, 2000; Watt, Russell, & Haslum, 2000). However, how design consultants can pursue effective briefing without a prior relationship and/or how they can go about in establishing new relationships with clients remain a concern for both scholars and practitioners of design.

The three practices for briefing and sales we uncovered in the reports of the consultants represent a practical response to the questions above by showcasing how the interviewed practitioners manage the evolving nature of design problems within the professional context of design consulting. They enabled the consultants to pursue more continuous and iterative briefing in the pre-project phase when engaging with clients with varying degrees of readiness in using design. In utilising the practices, the consultants strived to advance the design brief as much as possible prior to project commission. They did so by responding to the client’s readiness (customised communication) and systematising the discussions with potential clients (codified conduct) during the pre-project phase. By segmenting and offering only the ideation phase (Starter) or the explorative phase of the design process (Stint), they also circumvented some of the uncertainties for the client and iterated the problem over multiple projects (as opposed to pursuing it in a single project). The practices thereby exemplify the rationale of iterative briefing and the necessity of co-evolution of problem and solution spaces widely accepted in literature (e.g., Blyth & Worthington, 2001; Cross, 2006; Dorst & Cross, 2001; Phillips, 2004; Ryd, 2004).

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

The results of our study benefitted from the openness of the consultants in discussing their work during the interviews and the willingness of those consultants who shared related documents from their practice. Still, how briefing and sales play out in design consulting remains a challenging topic to study for scholars of design. In particular, the idiosyncratic and confidential nature of briefing makes accessing specific moments of briefing and sales a concern in devising future studies. As noted earlier, although consultants frequently discuss new projects with multiple potential clients in securing commissions, only a handful of these discussions result in a project, making it challenging for scholars to follow and directly observe the briefing and sales practices involved in design consulting. Further, the initial encounters for a project between a consultant and a potential client involve a sensitive exchange of information. The scope for a project should be set and a corresponding fee negotiated. Acting as a third (research) party in these discussions may not always be feasible. That said, in expanding on our findings, more longitudinal and/or ethnographic studies would be needed to gain a more direct knowledge about briefing and sales in design consulting, and their roles in forming relationships between design consultants and their clients. In particular, outlining reoccurring scenarios in the multitude of dynamic engagements and relationships between clients and design consultants, and pinpointing how the challenges found in our study can be referenced in different types of scenarios would be fruitful for future research.

Design is often grounded in a national and disciplinary context (e.g., Dormer, 1993). For the purposes of our study, we interviewed Finnish industrial design consultants about their work. The Finnish industrial design consulting scene is relatively small, which made it possible for us to get an overview of the main practices used among Finnish industrial design consultants. Finland is known for its industrial design thanks to the global success of manufacturing companies such as Fiskars, Kone, Metso, Nokia, Suunto and Wärtsilä. Design consultants have historically played an active role in establishing the reputation of industrial design in Finland by working with a broad spectrum of the industry (for a more in-depth discussion on the position of design and design consultants in Finnish industry, see Korvenmaa, 2001; Valtonen, 2007). The interviewed consultants follow this tradition, having worked on a range of different types of products for clients of varying size. That said, the practices pursued by Finnish design consultants may not be representative of those used in other geographical areas, or of those used in other subfields of design. Further, a close analysis of the extant literature suggests that briefing differs in different fields of design. For example, briefing in architecture is described to involve a variety of focused briefs over years of development (e.g., urban brief, strategic brief, project brief, fit-out brief) involving a wide range of users and stakeholders in different phases (e.g., Blyth & Worthington, 2001; Ryd & Fristedt, 2007). In contrast, guidelines for visual communication, packaging and advertising prescribe using a single brief, while emphasising an extensive review of the client’s portfolio and branding, competitors’ offering, and the retail spaces during the briefing process (e.g., Morrison et al., 2011; Phillips, 2004).

In probing such differences, future studies could be directed towards uncovering practices for briefing and sales in other geographical areas and/or in other fields of design consulting. A future study could, for instance, investigate design in the public sector and how the sales and briefing practices of design consultants differ in responding to the procurement practices of public rather than commercial (industry) organisations. As noted during the interviews, public procurements are regulated by law to be done through open competitions, making it potentially harder for public servants and design consultants to iterate a scope of a project and/or cultivate relationships over time. This situation could also be challenging for public sector organisations, as they may not be as able to take advantage of the benefits associated with establishing a longer-term relationship with a design consultant (Bruce & Docherty, 1993). To this end, we conclude this paper by noting that future studies should be directed towards exploring the peculiarities that may emerge from competing for public sector projects rather than commercial ones, and the alternative briefing and tender practices for such projects.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to all the interviewees taking time for our study and sharing their experiences in design consulting. We are also grateful to Sonja Meriläinen, Raimo Nikkanen, and Simo Puintila for referrals to interviewees and assistance in locating references on Finnish design consulting. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of the International Journal of Design for their constructive feedback that helped advance our manuscript.

Endnotes

- 1. For reference, the Finnish Association of Designer (Ornamo) provides agreement templates to its members.

- 2. Alternative pricing approaches discussed during the interviews include value-based pricing—where the fee for a project was based on the perceived worth for a client and royalties—where the consultant/designer were remunerated a percentage of the volume of production or sales of the product. However, these approaches were considered extremely rare by the interviewed consultants, and therefore fall out of foci of our study.

- 3. This adheres to the fact that a project duration may vary for the same project value. For example, 30 days project (30 K Euros worth) could be undertaken in 2 months, but it could also stretch to become 3 or 6 months depending on the delays and/or other relevant processes in and outside the client organization (e.g., suppliers, decisions for engineering or factory).

- 4. ‘Design Start’ was a government-support programme that ran between 2001 and 2006 for promoting the use of design in small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) in Finland. Initiated by the Ministry of Trade and Industry in association with the Employment and Economic Development Centre (Elykeskus in Finnish), the programme offered Finnish SMEs an opportunity to hire external design experts for a week at a subsidised cost of few hundred Euros. Although primarily praised for its intent during the interviews, some of the consultants mentioned that the unrealistic expectations of clients regarding the resources granted through the programme occasionally led to disputes. The fee of ‘Starter’ was notably higher (few thousand Euros) than Design Start (few hundred Euros). Nonetheless, Starter was still discussed as representing a lower-threshold procurement for many clients, as it seldom required longer approval chains for procurement within client organisations.

- 5. Although not clearly articulated as being productised, some of the other consultants passingly stated that they sometimes offer only the exploration phase as a stand-alone project to their clients. The main difference was that these offerings lacked working as a team with client personnel which was emphasised in Stint.

References

- Abecassis-Moedas, C., & Pereira, J. (2012). Incremental vs. radical innovation as a determinant of design position. In E. Bohemia, J. Liedtka, & A. Rieple (Eds.), Proceedings of the DMI International Research Conference: Leading innovation through design (pp. 563-570). Boston, MA: Design Management Institute.

- Bendixen, M., & Koch, C. (2007). Negotiating visualizations in briefing and design. Building Research & Information, 35(1), 42-53.

- Berends, H., Reymen, I., Stultiëns, R. G. L., & Peutz, M. (2011). External designers in product design processes of small manufacturing firms. Design Studies, 32(1), 86-108.

- Blyth, A., & Worthington, J. (2001). Managing the brief for better design. London, UK: Spon Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Bruce, M., & Docherty, C. (1993). It’s all in a relationship: A comparative study of client-design consultant relationships. Design Studies, 14(4), 402-422.

- Bruce, M., & Jevnaker, B. H. (Eds.). (1998). Management of design alliances sustaining competitive advantage. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bruce, M., & Morris, B. (1994). Managing external design professionals in the product development process. Technovation, 14(9), 585-599.

- Buchner, D., West, H., & Zaccai, G. (2000). Getting design: Bringing external design resources into an organisation. Design Management Journal, 11(2), 53-56.

- Calabretta, G., Gemser, G., Wijnberg, N., & Hekkert, P. (2012). Improving innovation strategic decision-making through the collaboration with design consultancies. In Proceedings of the DMI International Research Conference: Leading innovation through design (pp. 165-173). Boston, MA: Design Management Institute.

- Cooper, R., & Press, M. (1995). The design agenda : A guide to successful design management. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cox, S., & Hamilton, A. (1995). Architect’s job book (6th ed.). London, UK: RIBA Publications.

- Crilly, N., Blackwell, A. F., & Clarkson, P. J. (2006). Graphic elicitation: Using research diagrams as interview stimuli. Qualitative Research, 6(3), 341-366.

- Cross, N. (2006). Designerly ways of knowing. London, UK: Springer.

- Dankl, K. (2013). Style, strategy and temporality: How to write an inclusive design brief? The Design Journal, 16(2), 159-174.

- Dormer, P. (1993). Design since 1945. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson.

- Dorst, K., & Cross, N. (2001). Creativity in the design process: Co-evolution of problem-solution. Design Studies, 22(5), 425-437.

- Eriksson, P., & Kovalainen, A. (2008). Qualitative methods in business research. London, UK: Sage.

- Faugier, J., & Sargeant, M. (1997). Sampling hard to reach populations. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(4), 790-797.

- Finlay, L. (2002). Negotiating the swamp: The opportunity and challenge of reflexivity in research practice. Qualitative Research, 2(2), 209-230.

- Gorb, P., & Dumas, A. (1987). Silent design. Design Studies, 8(3), 150-156.

- Gwinner, K. P., Gremler, D. D., & Bitner, M. J. (1998). Relational benefits in services industries: The customer’s perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(2), 101-114.

- Hakatie, A., & Ryynänen, T. (2007). Managing creativity: A gap analysis approach to identifying challenges for industrial design consultancy services. Design Issues, 23(1), 28-46.

- Haug, A. (2015). Emergence patterns for client design requirements. Design Studies, 39, 48-69.

- Hey, J. H. G., Joyce, C. K., & Beckman, S. L. (2007). Framing innovation: Negotiating shared frames during early design phases. Journal of Design Research, 6(1), 79-99.

- Jevnaker, B. H. (2005). Vita activa: On relationships between design(ers) and business. Design Issues, 21(3), 25-48.

- Jevnaker, B. H., & Bruce, M. (1998). Design alliances: The hidden assets in management of strategic innovation. The Design Journal, 1(1), 24-40.

- Jin, Y., & Chusilp, P. (2006). Study of mental iteration in different design situations. Design Studies, 27(1), 25-55.

- Korvenmaa, P. (2001). Rhetoric and action: Design policies in Finland at the beginning of the third millennia. Scandinavian Journal of Design History, 11, 7-15.

- Kurvinen, E. (2005). How industrial design interacts with technology: A case study on design of a stone crusher. Journal of Engineering Design, 16(4), 373-383.

- Lawson, B. (2004). What designers know (1st ed.). Oxford, UK: Architectural Press.

- Lewis, J., Ritchie, J., Ormston, R., & Morrell, G. (2014). Generalising from qualitative research. In J. Ritchie, J. Lewis, C. M. Nicholls, & R. Ormston (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (pp. 347-366). London, UK: Sage.

- Luck, R., Haenlein, H., & Bright, K. (2001). Project briefing for accessible design. Design Studies, 22(3), 297-315.

- Maher, M. L., & Poon, J. (1996). Modelling design exploration as co-evolution. Microcomputers in Civil Engineering, 11(3), 195-210.

- Marshall, M. N. (1996). Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice, 13(6), 522-525.

- Martin, R. C. (2003). Agile software development: Principles, patterns, and practices. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Micheli, P. (2014). Leading business by design: Why and how business leaders invest in design. London, UK: Design Council & Warwick Business School.

- Morrison, D., Knox, S., Ellis, R., & Pringle, H. (2011). Briefing an agency: A best practice guide to briefing communications agencies (2nd ed.). London, UK: IPA.

- O’Connor, W. J. (2000). Good chemistry: Client and consultant relationships to uncover the big idea. Design Management Journal, 11(2), 20-27.

- Ormston, R., Spencer, L., Barnard, M., & Snape, D. (2014). The foundations of qualitative research. In J. Ritchie, J. Lewis, C. M. Nicholls, & R. Ormston (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (pp. 1-25). London, UK: Sage.

- Paton, B., & Dorst, K. (2011). Briefing and reframing: A situated practice. Design Studies, 32(6), 573-587.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Perks, H., Cooper, R., & Jones, C. (2005). Characterizing the role of design in new product development: An empirically derived taxonomy. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 22(2), 111-127.

- Person, O., Snelders, D., & Schoormans, J. (2016). Assessing the performance of styling activities: An interview study with industry professionals in style-sensitive companies. Design Studies, 42, 33-55.

- Phillips, P. L. (2004). Creating the perfect design brief (1st ed.). New York, NY: Allworth Press.

- Pratt, M. G. (2008). Fitting oval pegs into round holes. Organizational Research Methods, 11(3), 481-509.

- Pratt, M. G. (2009). From the editors–For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 856-862.

- Ramlau, U. H. (2004). In Denmark, design tops the agenda. Design Management Review, 15(4), 48-54.

- Rees, H. (1997). Patterns of making: Thinking and making in industrial design. In P. Dormer (Ed.), The culture of craft: Status and future (pp. 116-136). Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, R. (Eds.). (2014). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London, UK: Sage.

- Ryd, N. (2004). The design brief as carrier of client information during the construction process. Design Studies, 25(3), 231-249.

- Ryd, N., & Fristedt, S. (2007). Transforming strategic briefing into project briefs. Facilities, 25(5/6), 185-202.

- Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage.

- Schön, D. A. (1995). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Aldershot, UK: Arena.

- Smith, R. P., & Tjandra, P. (1998). Experimental observation of iteration in engineering design. Research in Engineering Design, 10(2), 107-117.

- Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., & O’Connor, W. (2003). Analysis: Practice, Principles and Processes. In J. Ritchie, & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (pp. 199-218). London, UK: Sage.

- Thurmond, V. A. (2001). The point of triangulation. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33(3), 253-258.

- Tomes, A., Oates, C., & Armstrong, P. (1998). Talking design: Negotiating the verbal-visual translation. Design Studies, 19(2), 127-142.

- Tzortzopoulos, P., Cooper, R., Chan, P., & Kagioglou, M. (2006). Clients’ activities at the design front-end. Design Studies, 27(6), 657-683.

- Valminen, K., & Toivonen, M. (2012). Seeking efficiency through productisation: A case study of small KIBS participating in a productisation project. The Service Industries Journal, 32(2), 273-289.

- Valtonen, A. (2007). Redefining industrial design - Changes in the design practice in Finland. Helsinki, Finland: University of Art and Design Helsinki.

- von Stamm, B. (1998). Whose design is it? The use of external designers. The Design Journal, 1(1), 41-53.

- Watt, C., Russell, K., & Haslum, M. (2000). Stronger relationships make stronger design solutions. Design Management Journal, 11(2), 46-52.

- Wild, P. J., McMahon, C., Darlington, M., Liu, S., & Culley, S. (2010). A diary study of information needs and document usage in the engineering domain. Design Studies, 31(1), 46-73.

Appendix

Appendix 1. Interview topic guide.

Appendix 2. Final code system.

The main codes from the focused coding cover (in alphabetical order):

- Background information about the design consultants and the consultancies they worked for

- Briefing procedures in terms of what takes place and in what order

- Changes during projects in terms of why they happen and how they are dealt with

- Design objects (products) in terms of the types mentioned during the interviews

- Documentation in terms of the purpose, components, and authorship

- Meeting information in terms of purpose and preparation

- Sales activities in terms of how new clients were sought and how they were approached.

The main codes from the axial coding include (in alphabetical order):

- Client type in terms of the size of clients (small to large, and local to international)

- Design readiness in terms of the capacity or culture of (potential) clients to work with design (low to high)

- Project types in terms of the scope of projects (cosmetic to radical)

Appendix 3. One of the research diagrams with an interview’s notes and scribble.

Appendix 4. The benefits of having long-term relationships and utilising the adapted practices as discussed by the design consultants a.

Appendix 5. Sources of change and corresponding quotes.

Appendix 6. Sub-themes of readiness of client companies and corresponding and exemplary quotes.